Christophe Boucher, College of Charleston, American Studies, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781 Eric J

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-10-2019 Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781 Eric J. Toups University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Toups, Eric J., "Black Robes at the Edge of Empire: Jesuits, Natives, and Colonial Crisis in Early Detroit, 1728-1781" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2958. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/2958 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLACK ROBES AT THE EDGE OF EMPIRE: JESUITS, NATIVES, AND COLONIAL CRISIS IN EARLY DETROIT, 1728-1781 By Eric James Toups B.A. Louisiana State University, 2016 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2019 Advisory Committee: Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Advisor Stephen Miller, Adelaide & Alan Bird Professor and History Department Chair Liam Riordan, Professor of History BLACK ROBES AT THE EDGE OF EMPIRE: JESUITS, NATIVES, AND COLONIAL CRISIS IN EARLY DETROIT, 1728-1781 By Eric James Toups Thesis Advisor: Dr. Jacques Ferland An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (in History) May 2019 This thesis examines the Jesuit missionaries active in the region of Detroit and how their role in that region changed over the course of the eighteenth century and under different colonial regimes. -

The Mckee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes

The McKee Treaty of 1790: British-Aboriginal Diplomacy in the Great Lakes A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN Saskatoon by Daniel Palmer Copyright © Daniel Palmer, September 2017 All Rights Reserved Permission to Use In presenting this thesis/dissertation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis/dissertation in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis/dissertation work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis/dissertation or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis/dissertation. Requests for permission to copy or to make other uses of materials in this thesis/dissertation in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History HUMFA Administrative Support Services Room 522, Arts Building University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 i Abstract On the 19th of May, 1790, the representatives of four First Nations of Detroit and the British Crown signed, each in their own custom, a document ceding 5,440 square kilometers of Aboriginal land to the Crown that spring for £1200 Quebec Currency in goods. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Native Americans, Europeans, and the Raid on Pickawillany

ABSTRACT “THE LAND BELONGS TO NEITHER ONE”: NATIVE AMERICANS, EUROPEANS, AND THE RAID ON PICKAWILLANY In 1752, the Miami settlement at Pickawillany was attacked by a force of Ottawa and Chippewa warriors under the command of a métis soldier from Canada. This raid, and the events that precipitated it, is ideally suited to act as a case study of the role of Native American peoples in the Ohio Country during the first half of the eighteenth century. Natives negotiated their roles and borders with their British and French neighbors, and chose alliances with the European power that offered the greatest advantage. Europeans were alternately leaders, partners, conquerors and traders with the Natives, and exercised varying levels and types of control over the Ohio Country. Throughout the period, each of the three groups engaged in a struggle to define their roles in regards to each other, and to define the borders between them. Pickawillany offers insights into this negotiation. It demonstrates how Natives were not passive victims, but active, vital agents who acted in their own interest. The events of the raid feature a number of individuals who were cultural brokers, intermediaries between the groups who played a central, but tenuous, role in negotiations. It also exhibits the power of ritual violence, a discourse of torture and maiming that communicated meanings to friends and rivals alike, and whose implications shaped the history of the period and perceptions of Natives. Luke Aaron Fleeman Martinez May 2011 “THE LAND BELONGS TO NEITHER ONE”: -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 155/Tuesday, August 11, 2020

48556 Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 155 / Tuesday, August 11, 2020 / Notices CO 80205, telephone (303) 370–6056, SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Notice is Affairs; performed a skeletal and email [email protected], by here given in accordance with the dentition analysis on October 25, 1995. September 10, 2020. After that date, if Native American Graves Protection and Although the exact date or pre-contact no additional requestors have come Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), 25 U.S.C. period associated with this site is forward, transfer of control of the 3003, of the completion of an inventory unknown, as no reliable temporal human remains and associated funerary of human remains under the control of indictors were recovered or recorded, objects to The Tribes may proceed. the Bruce Museum, Greenwich, CT. The the Shorakapock site is well The Denver Museum of Nature & human remains were removed from the documented in the New York Science and the U.S. Department of Shorakapock Site in Inwood Hill Park, archeological and historical literature. Agriculture, Forest Service, Gila New York County, NY. Records from 17th and 18th century National Forest are responsible for This notice is published as part of the documents indicate at least five notifying The Tribes that this notice has National Park Service’s administrative settlements may been located within or been published. responsibilities under NAGPRA, 25 near the Inwood Hill Park vicinity. According to The Cultural Landscape Dated: July 7, 2020. U.S.C. 3003(d)(3). The determinations in this notice are the sole responsibility of Foundation, the site was inhabited by Melanie O’Brien, the Lenape tribe through the Manager, National NAGPRA Program. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

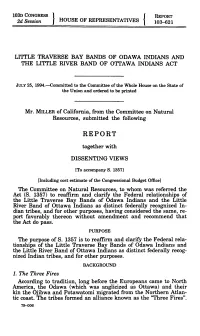

REPORT 2D Session HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES 103-621

103D CONGRESS } { REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 103-621 LITTLE TRAVERSE BAY BANDS OF ODAWA INDIANS AND THE LITTLE RIVER BAND OF OTrAWA INDIANS ACT JULY 25, 1994.-Committed to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed Mr. MILLER of California, from the Committee on Natural Resources, submitted the following REPORT together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany S. 13571 [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Natural Resources, to whom was referred the Act (S.1357) to reaffirm and clarify the Federal relationships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recognized In- dian tribes, and for other purposes, having considered the same, re- port favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the Act do pass. PURPOSE The purpose of S. 1357 is to reaffirm and clarify the Federal rela- tionships of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians and the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians as distinct federally recog- nized Indian tribes, and for other purposes. BACKGROUND 1. The Three Fires According to tradition, long before the Europeans came to North America, the Odawa (which was anglicized as Ottawa) and their kin the Ojibwa and Potawatomi migrated from the Northern Atlan- tic coast. The tribes formed an alliance known as the "Three Fires". 79-006 The Ottawa/Odawa settled on the eastern shore of Lake Huron at what are now called the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island. In 1615, the Ottawa/Odawa formed a fur trading alliance with the French. -

The INDIAN CHIEFS of PENNSYLVANIA by C

WENNAWOODS PUBLISHING Quality Reprints---Rare Books---Historical Artwork Dedicated to the preservation of books and artwork relating to 17th and 18th century life on America’s Eastern Frontier SPRING & SUMMER ’99 CATALOG #8 Dear Wennawoods Publishing Customers, We hope everyone will enjoy our Spring‘99 catalog. Four new titles are introduced in this catalog. The Lenape and Their Legends, the 11th title in our Great Pennsylvania Frontier Series, is a classic on Lenape or Delaware Indian history. Originally published in 1885 by Daniel Brinton, this numbered title is limited to 1,000 copies and contains the original translation of the Walum Olum, the Lenape’s ancient migration story. Anyone who is a student of Eastern Frontier history will need to own this scarce and hard to find book. Our second release is David Zeisberger’s History of the Indians of the Northern American Indians of Ohio, New York and Pennsylvania in 18th Century America. Seldom does a book come along that contains such an outstanding collection of notes on Eastern Frontier Indian history. Zeisberger, a missionary in the wilderness among the Indians of the East for over 60 years, gives us some of the most intimate details we know today. Two new titles in our paperback Pennsylvania History and Legends Series are: TE-A-O-GA: Annals of a Valley by Elsie Murray and Journal of Samuel Maclay by John F. Meginness; two excellent short stories about two vital areas of significance in Pennsylvania Indian history. Other books released in last 6 months are 1) 30,000 Miles With John Heckewelder or Travels Among the Indians of Pennsylvania, New York, Ohio in the 18th Century, 2) Early Western Journals, 3) A Pennsylvania Bison Hunt, and 4) Luke Swetland’s Captivity. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 179/Tuesday

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 179 / Tuesday, September 15, 2020 / Notices 57237 Band of Potawatomi Nation, Kansas); organizations and has determined that Community, Michigan; Keweenaw Bay Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior there is no cultural affiliation between Indian Community, Michigan; Lac Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; Red the human remains and associated Vieux Desert Band of Lake Superior Lake Band of Chippewa Indians, funerary objects and any present-day Chippewa Indians of Michigan; Little Minnesota; Saginaw Chippewa Indian Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian River Band of Ottawa Indians, Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Marie organizations. Representatives of any Michigan; Little Traverse Bay Bands of Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan; Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian Odawa Indians, Michigan; Match-e-be- Shawnee Tribe; Sokaogon Chippewa organization not identified in this notice nash-she-wish Band of Pottawatomi Community, Wisconsin; St. Croix that wish to request transfer of control Indians of Michigan; Nottawaseppi Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin; of these human remains and associated Huron Band of the Potawatomi, Stockbridge Munsee Community, funerary objects should submit a written Michigan (previously listed as Huron Wisconsin; Turtle Mountain Band of request to Michigan State University. If Potawatomi, Inc.); Pokagon Band of Chippewa Indians of North Dakota; and no additional requestors come forward, Potawatomi Indians, Michigan and the Wyandotte Nation (hereafter referred transfer of control of the human remains Indiana; Saginaw Chippewa Indian to as ‘‘The Tribes’’). and associated funerary objects to the Tribe of Michigan; Sault Ste. Marie Indian Tribes or Native Hawaiian Additional Requestors and Disposition Tribe of Chippewa Indians, Michigan; organizations stated in this notice may and two non-federally recognized Representatives of any Indian Tribes proceed. -

![People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7487/people-of-the-three-fires-the-ottawa-potawatomi-and-ojibway-of-michigan-workbook-and-teachers-guide-1467487.webp)

People of the Three Fires: the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan.[Workbook and Teacher's Guide]

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 321 956 RC 017 685 AUTHOR Clifton, James A.; And Other., TITLE People of the Three Fires: The Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway of Michigan. Workbook and Teacher's Guide . INSTITUTION Grand Rapids Inter-Tribal Council, MI. SPONS AGENCY Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C.; Dyer-Ives Foundation, Grand Rapids, MI.; Michigan Council for the Humanities, East Lansing.; National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-9617707-0-8 PUB DATE 86 NOTE 225p.; Some photographs may not reproduce ;4011. AVAILABLE FROMMichigan Indian Press, 45 Lexington N. W., Grand Rapids, MI 49504. PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Guides - Classroom Use - Guides '.For Teachers) (052) -- Guides - Classroom Use- Materials (For Learner) (051) EDRS PRICE MFU1 /PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Culture; *American Indian History; American Indians; *American Indian Studies; Environmental Influences; Federal Indian Relationship; Political Influences; Secondary Education; *Sociix- Change; Sociocultural Patterns; Socioeconomic Influences IDENTIFIERS Chippewa (Tribe); *Michigan; Ojibway (Tribe); Ottawa (Tribe); Potawatomi (Tribe) ABSTRACT This book accompanied by a student workbook and teacher's guide, was written to help secondary school students to explore the history, culture, and dynamics of Michigan's indigenous peoples, the American Indians. Three chapters on the Ottawa, Potawatomi, and Ojibway (or Chippewa) peoples follow an introduction on the prehistoric roots of Michigan Indians. Each chapter reflects the integration -

Archaeologist Volume 57 No

OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST VOLUME 57 NO. 1 WINTER 2007 PUBLISHED BY THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF OHIO The Archaeological Society of Ohio BACK ISSUES OF OHIO ARCHAEOLOGIST 1956 thru 1967 out of print Term 1968 - 1999 $ 2.50 Expires A.S.O. OFFICERS 1951 thru 1955 REPRINTS - sets only $100.00 2008 President Rocky Falleti, 5904 South Ave., Youngstown, OH 2000 thru 2002 $ 5.00 44512(330)788-1598. 2003 $ 6.00 2008 Vice President Michael Van Steen, 5303 Wildman Road, Add $0.75 For Each Copy of Any Issue South Charleston, OH 45314. The Archaeology of Ohio, by Robert N. Converse regular $60.00 Author's Edition $75.00 2008 Immediate Past President John Mocic, Box 170 RD #1, Dilles Postage, Add $ 2.50 Bottom, OH 43947 (740) 676-1077. Back issues of the Ohio Archaeologist printed prior to 1964 are generally 2008 Executive Secretary George Colvin, 220 Darbymoor Drive, out of print but copies are available from time to time. Write to business office Plain City, OH 43064 (614) 879-9825. for prices and availability. 2008 Treasurer Gary Kapusta, 32294 Herriff Rd., Ravenna, OH 44266 ASO CHAPTERS (330) 296-2287. Aboriginal Explorers Club 2008 Recording Secretary Cindy Wells, 15001 Sycamore Road, President: Mark Kline, 1127 Esther Rd., Wellsville, OH 43968 (330) 532-1157 Mt. Vernon, OH 43050 (614) 397-4717. Beau Fleuve Chapter 2008 Webmaster Steven Carpenter, 529 Gray St., Plain City, OH. President: Richard Sojka, 11253 Broadway, Alden, NY 14004 (716) 681-2229 43064 (614) 873-5159. Blue Jacket Chapter 2010 Editor Robert N. Converse, 199 Converse Drive, Plain City, President: Ken Sowards, 9201 Hildgefort Rd„ Fort Laramie, OH 45845 (937) 295-3764 OH 43064(614)873-5471. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot.