The Apocryphal Acts of the Apostles in the Latin Middle Ages: Contexts of Transmission and Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

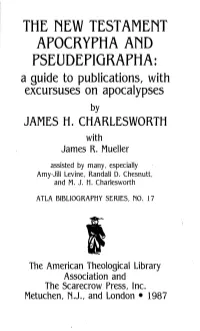

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA and PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a Guide to Publications, with Excursuses on Apocalypses by JAMES H

THE NEW TESTAMENT APOCRYPHA AND PSEUDEPIQRAPHA: a guide to publications, with excursuses on apocalypses by JAMES H. CHARLESWORTH with James R. Mueller assisted by many, especially Amy-Jill Levine, Randall D. Chesnutt, and M. J. H. Charlesworth ATLA BIBLIOGRAPHY SERIES, MO. 17 The American Theological Library Association and The Scarecrow Press, Inc. Metuchen, N.J., and London • 1987 CONTENTS Editor's Foreword xiii Preface xv I. INTRODUCTION 1 A Report on Research 1 Description 6 Excluded Documents 6 1) Apostolic Fathers 6 2) The Nag Hammadi Codices 7 3) The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha 7 4) Early Syriac Writings 8 5) Earliest Versions of the New Testament 8 6) Fakes 9 7) Possible Candidates 10 Introductions 11 Purpose 12 Notes 13 II. THE APOCALYPSE OF JOHN—ITS THEOLOGY AND IMPACT ON SUBSEQUENT APOCALYPSES Introduction . 19 The Apocalypse and Its Theology . 19 1) Historical Methodology 19 2) Other Apocalypses 20 3) A Unity 24 4) Martyrdom 25 5) Assurance and Exhortation 27 6) The Way and Invitation 28 7) Transference and Redefinition -. 28 8) Summary 30 The Apocalypse and Its Impact on Subsequent Apocalypses 30 1) Problems 30 2) Criteria 31 3) Excluded Writings 32 4) Included Writings 32 5) Documents , 32 a) Jewish Apocalypses Significantly Expanded by Christians 32 b) Gnostic Apocalypses 33 c) Early Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 34 d) Early Medieval Christian Apocryphal Apocalypses 36 6) Summary 39 Conclusion 39 1) Significance 39 2) The Continuum 40 3) The Influence 41 Notes 42 III. THE CONTINUUM OF JEWISH AND CHRISTIAN APOCALYPSES: TEXTS AND ENGLISH TRANSLATIONS Description of an Apocalypse 53 Excluded "Apocalypses" 54 A List of Apocalypses 55 1) Classical Jewish Apocalypses and Related Documents (c. -

FATHERS Church

FOC_TPages 9/12/07 9:47 AM Page 2 the athers Fof the Church A COMPREHENSIVE INTRODUCTION HUBERTUS R. DROBNER Translated by SIEGFRIED S. SCHATZMANN with bibliographies updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless, SJ, and Hubertus R. Drobner K Hubertus R. Drobner, The Fathers of the Church Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group, © 2007. Used by permission. _Drobner_FathersChurch_MiscPages.indd 1 11/10/15 1:30 PM The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction English translation © 2007 by Hendrickson Publishers Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. P. O. Box 3473 Peabody, Massachusetts 01961-3473 ISBN 978-1-56563-331-5 © 2007 by Baker Publishing Group The Fathers of the Church: A Comprehensive Introduction, by Hubertus R. Drobner, withPublished bibliographies by Baker Academic updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless,a division of SJ, Baker and Hubertus Publishing Drobner, Group is a translation by Siegfried S. Schatzmann ofP.O.Lehrbuch Box 6287, der Grand Patrologie. Rapids,© VerlagMI 49516-6287 Herder Freiburg im Breisgau, 1994. www.bakeracademic.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any Baker Academic paperback edition published 2016 formISBN or978-0-8010-9818-5 by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, record- ing, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writingPreviously from published the publisher. in 2007 by Hendrickson Publishers PrintedThe Fathers in the of Unitedthe Church: States A ofComprehensive America Introduction, by Hubertus R. Drobner, with bibliographies updated and expanded for the English edition by William Harmless, SecondSJ, and PrintingHubertus — Drobner, December is a 2008 translation by Siegfried S. -

New Perspectives on Early Christian and Late Antique Apocryphal Texts and Traditions

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament Herausgeber / Editor Jörg Frey (Zürich) Mitherausgeber / Associate Editors Markus Bockmuehl (Oxford) · James A. Kelhoffer (Uppsala) Hans-Josef Klauck (Chicago, IL) · Tobias Nicklas (Regensburg) J. Ross Wagner (Durham, NC) 349 Rediscovering the Apocryphal Continent: New Perspectives on Early Christian and Late Antique Apocryphal Texts and Traditions Edited by Pierluigi Piovanelli and Tony Burke With the collaboration of Timothy Pettipiece Mohr Siebeck Pierluigi Piovanelli, born 1961; 1987 MA; 1992 PhD; Professor of Second Temple Judaism and Early Christianity at the University of Ottawa (Ontario, Canada). Tony Burke, born 1968; 1995 MA; 2001 PhD; Associate Professor of Early Christianity at York University (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). ISBN 978-3-16-151994-9 / eISBN 978-3-16-157495-5 unveränderte eBook-Ausgabe 2019 ISSN 0512-1604 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum NeuenT estament) Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. www.mohr.de This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher’s written permission. This applies particularly to reproduc- tions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was typeset by Martin Fischer inT übingen using Minion Pro typeface, printed by Gulde-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Otters- weier. Printed in Germany. This volume is dedicated to the memories of Pierre Geoltrain (1929–2004) and François Bovon (1938–2013), without whom nothing of this would have been possible. -

Miracle and Mission. the Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark

Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament • 2. Reihe Herausgegeben von Martin Hengel und Otfried Hofius 112 ARTI BUS James A. Kelhoffer Miracle and Mission The Authentication of Missionaries and Their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark Mohr Siebeck JAMES A. KELHOFFER, born 1970; 1991 B.A. Wheaton College (IL); 1992 M.A. Wheaton Grad- uate School (IL); 1996 M.A. University of Chicago; 1999 Ph.D. University of Chicago; 1999- 2000 Visiting Assistant Professor of New Testament at the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago. Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Kelhoffer, James A.: Miracle and mission : the authentication of missionaries and their message in the longer ending of Mark / James A. Kelhoffer. - Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2000 (Wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zum Neuen Testament: Reihe 2 ; 112) ISBN 3-16-147243-8 © 2000 by J.C.B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck), P.O. Box 2040, D-72010 Tübingen. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. The applies particularly to repro- ductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper from Papierfabrik Nie- fern and bound by Heinr. Koch in Tübingen. Printed in Germany. ISSN 0340-9570 To my grandparents: Elsie Krath Alberich Anthony Henry Alberich Lillian Jay Kelhoffer f Herbert Frank Kelhoffer, Sr. Magnum opus et adruum, sed Deus adiutor noster est. (Augustine, de civ. D. Preface) Acknowledgments This book is a revision of my doctoral dissertation, "The Authentication of Missionaries and their Message in the Longer Ending of Mark (Mark 16:9-20)," written under the supervision of Adela Yarbro Collins at the University of Chicago and defended on December 9,1998. -

Scriptures in Early Christianity

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR SCRIPTURES IN EARLY CHRISTIANITY Outi Lehtipuu and Hanne von Weissenberg What did early Christians conceive of as scripture? What texts did they read and use? Who read and used them? How were the books that are now included in the biblical canon chosen? Finding answers to these questions is challenging, not least because of the scarcity of evidence, particularly on the earliest times. Even though scriptures assumed a constitutive role for Jesus’ followers from the beginning and early Christian writers constantly appealed to authoritative texts, there is surprisingly little discussion on what actual books were regarded as scripture before the fourth century. It is only then when the term kanōn starts to be used in the meaning of a list of normative books (Metzger 1987: 289–293). Another challenge has to do with perspective: it is not easy to approach the question of early Jewish or Christian scriptures without having in mind the closed canon familiar to scholars today (Brakke 2012: 266–267; Najman 2012: 497–518.). This means that historians tend to read sources from within the framework of a fixed list of scriptures and evaluate how close to the ultimate goal, the closed canon, each piece of evidence arrives (Mroczek 2015). Historically this kind of a teleological design is problematic – using a standard which did not exist prior to the fourth century does not do justice to earlier sources. The same goes with nomenclature (Ulrich 2002a; Zahn 2011). It makes little sense to speak of ‘canonical’ and ‘non-canonical’ texts in a situation where there was no canon. -

The Call of the First Disciples, Philip and Nathanael

LTL2: The Ministry Years 1.08 Notes The call of the first disciples, Philip and Nathaniel The Call of the First Disciples, Philip and Nathanael JCV Integrated Text: John 1:43-51 On the next day, Jesus wanted to set out towards Galilee, and He found Philip and Jesus said to him, "Travel with me." Now Philip was from Bethsaida, the same town as Andrew and Peter. Philip found Nathanael, and said to him, “We have found the one that Moses wrote of in the law and the prophets: Jesus the son of Joseph from Nazareth.” But Nathaniel answered, “Can anything good come out of Nazareth?” Philip retorted, “Come and see.” Jesus saw Nathanael coming toward Him, and said about him, “Look at this, genuinely an Israelite in whom there is no trickiness!” Nathanael responded, “How do you know me?” Jesus answered him, “Before Philip called you, when you were under the fig tree, I saw you.” Nathanael started to speak, saying: "Rabbi, you are the Son of God! You are the King of Israel!" Jesus answered and said to him, “You trust me because I told you, ‘I saw you underneath the fig tree?' You will see greater things than these!” And He said to him, “Really truly, I tell you all, from today you will see heaven opened, and the angels of God ascending and descending on the Son of Man.” Introduction These notes are divided into two sections to follow the relatedLTL2 Living The Ministry Years 1.08a/b videos: • Part A – more detail about Philip and Nathanael and their conversation • Part B – the detail of the conversation between Jesus and Nathanael Part A – Philip and Nathanael Jesus has just called Andrew and Simon Peter the day before. -

St. Teresa of Avila Catholic Church M 21, 2021

MASS INTENTIONS S T' G T We Welcome You To As we celebrate Mass together we include in our prayers: St. Teresa of Avila Catholic Church Are you a sustainability enthusiast? Have you Saturday, March 20 been building consistent, sustainable habits to Served by the Carmelites 4:15pm Dan Perea reduce your carbon footprint, especially Sunday, March 21 through this unusual past year? Do you have M 21, 2021 8:30am Fr. Peter Sammon any ps that you would like to share with your The People of the Parish faith family? Email the green team F S 10:00am Kathleen Uhlhorn (Spec. Int.) [email protected] to be featured in O L Tuesday, March 23 upcoming bullens! And remember, even 8:30am Rachael Humphrey small efforts can add up to great results, so 1490 19 S (C) Friday, March 26 don’t be shy! L NE C 19 C S 8:30am Connie Brown (Spec. Int.) PASTOR S M M Saturday, March 27 AAA 2020—Week 2 Rev. Michael A. Greenwell, O. Carm. Saturday Vigil 4:15 pm Please call 6 months 4:15pm James J. Burns, Sr. [email protected] Sunday 8:30 & in advance The People of the Parish Assessed Amount: $29,486 PAROCHIAL VICAR 10:00 am Amount Pledged: $17,270 Rev. Michael Kwiecien, O. Carm. B Sunday, March 28 W M Balance Remaining: $12,216 [email protected] R 8:30am Tillie Diaz Tuesday 8:30 am PARISH SECRETARY Please call for an 10:00am Kathleen Uhlhorn (Spec. Int.) We are at 59% of our goal! Thank you to all Friday 8:30 am appointment Stephani Sheehan, [email protected] who have donated & pledged. -

Why Do Gnostics Consider Mary Magdalene the Greatest Apostle?

Why Do Gnostics Consider Mary Magdalene the Greatest Apostle? BY MIGUEL CONNER · JULY 15, 2015 Mainstream Christianity has many views of Mary Magdalene. She is a penitent sinner, a redeemed prostitute, the first witness to the Resurrection, the messenger to the Apostles, and a source of erotic inspiration for artists throughout history. Mary Magdalene is a complex, misunderstood, and marginalized figure in Orthodoxy, a symbol for the plight of females within the Christian religion. But in Gnosticism her role is clearly defined—Mary Magdalene is not only the main Apostle to the living Christ but a Gnostic leader for the ages. This declaration is perhaps ironic since Gnostics have a tendency to continually re- interpret and re-evaluate Biblical characters to suit their spiritual explorations. But there’s something about Mary. One of the most thorough expositions on the Gnostic Mary Magdalene comes from Jane Schaberg’s The Resurrection of Mary Magdalene. Schaberg lists nine characteristics that define the consort of Jesus Christ, as she is known in Gnostic and Apocryphal texts: 1) Mary is Prominent. The Magdalene is a main protagonist whenever she appears. In The Dialogue of the Savior, Mary is considered a “sister,” an equal to those entrusted with spreading the light of Gnosis. In The Gospel of Philip, she is one who “always walks with the Lord,” a privilege only enjoyed by Enoch and Noah in the entire Bible. Mary replaces the two Patriarchs of the Old Testament as a favorite of the Divine in the new dispensation. In The Pistis Sophia, Mary is the most outstanding student of Jesus, the chief questionnaire who gives the most insightful answers. -

The Twelve – a Study of the Apostles by James F

The Twelve – A Study of the Apostles By James F. Korthals [Bible Class January – February 2000, David’s Star Lutheran Church, Jackson, WI] What is Discipleship? “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations. .” That was His last word, His great commission. We are far from the mark if we think of our relationship with Jesus Christ in terms of anything less than full discipleship. He didn’t say “Go and make churchgoers,” or “Go and make congregation members.” Of course His disciples of the twentieth century will go to church and they will be congregation members. But they must become His disciples first of all. And they must live their Christian faith in terms of a personal discipleship with their Lord and Redeemer. (John H. Baumgaertner) 1. A disciple is a person who has a relationship with the Master A. Mark 3:14 B. Matthew 13:10-11 C. Matthew 26:38 D. Matthew 28:7,10 E. Matthew 12:49 2. A disciple is a person who is under the total authority of the Master A. Luke 14:26 B. Luke 14:33 C. Matthew 10:24 and Matthew 16:24 3. A disciple is a person who learns from the Master A. Three characteristics of our “learning” 1. Matthew 16:24 2. Matthew 11:29 3. John 8:31 B. Five characteristics of his “teaching” 1. Luke 11:1 2. Mark 4:33-34 3. Matthew 16:20 4. Matthew 16:21 5. Mark 8:33 4. A disciple is useful to his Master A. Luke 10:2 B. -

0 Contents.Qxd

The Post-Apostolic Era Chart 18-10 New Testament Apocrypha Explanation The word apocrypha derives from a Greek word meaning “hidden away.” It was origi- nally used to refer to books kept hidden away since they had not been canonized. Many of these books claim to have been written by the apostles. It is not impossible that some of them derive, at least in part, from actual apostolic writings. Some apocryphal books exist today; others remain lost. Some existing books have been available since ancient times; others have been rediscovered during the past century as a result of archaeological research. Chart - groups these apocryphal books in a wide variety of genres including gospels, apocalyptic writings (book of Revelation), treatises, letters, acts, and liturgies. The chart gives the titles of these apocryphal writings, known in whole or by fragmentary remains, or simply mentioned in other writings. These writings are useful in tracing the change and development of various ideas in the early centuries of Christianity. If studied carefully and with enlightenment of the Spirit, New Testament apocryphal writings, like the Old Testament Apocrypha, can be beneficial, although “there are many things contained therein that are not true, which are interpolations by the hands of men” (D&C 91:2). References Edgar Hennecke, New Testament Apocrypha (Philadelphia: Westminster, 1963). Stephen J. Patterson, “Apocrypha, New Testament,” ABD, 1:94–97. C. Wilfred Griggs, “Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha,” EM, 1:55–56. Charting the New Testament, © 2002 Welch, Hall, FARMS New Testament Apocrypha 1. GOSPELS AND RELATED FORMS Narrative Gospels The Gospel of Mary The Gospel of the Ebionites The Gospel of Philip The Gospel of the Hebrews The Epistula Apostolorum (a revela- The Gospel of the Nazoreans tion discourse cast in an epistolary The Gospel of Nicodemus (The framework) Acts of Pilate) The Gospel of the Egyptians (distinct The Gospel of Peter from the Coptic Gospel of the The Infancy Gospel of Thomas Egyptians) P. -

The Gnostic Conception of the Cross."

JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OJ' ~ht iji,ct11rin -Jnstitut~, Jgilosopbital Socid~ of ~nat Jritain. GBNEI!,lL SBCI!ETAJU': L11cruxB S11cR11r,111r: E. J. SEWELL. E. WALTER MAUNDER, F.R.A.S. VOL. L. LONDON: (~ullltdt,tll tip ~r indtftutr, 1, ~mtraI JSuiillingd, mltrdtmtndter, j,.a!l. 1.) ALL BIGHTI IIBIBBTMD, 1918. 599TH ORDINARY GENERAL MEETING, HELD IN COMMITTEE ROOM B, CENTRAL BUILDINGS, WESTMINSTER, ON MONDAY, APRIL 15TH, 1918, AT 4.30 P.M. THE REV. H. J. R. MARSTON, M.A., IN THE OHAIR. The Minutes of the previous Meeting were read, confirmed, and signed. The HoN. SECRETARY announ<'ed the election as Associates of the Rev. Dr. M. G. Kyle and Edward P. Vining, Esq., LL.D. The rules regulating the discussion following the papers were read; and in the absence of the Rev. Dr. MacCulloch the Chairman requested the Secretary to read the Canon's paper on "The Gnostic Conception of the Cross." THE GNOSTIC CONCEPTION OF THE CROSS. By Canon J. A. MAcCULJ,OCH, D.D., Rector of S. Saviour's, Bridge of Allan. N its original form Gnosticism may be described as an extra I Christian, and doubtless also a pre-Christian, religious syncretism, which aimed at enlightening men through esoteric means and ritual. Later, its prominent teachers laid hold of Christian doctrines, especially those relating to the Person of Christ, adapting these freely to their own views, and thus presenting a misleading likeness to Christianity. A pre liminary sketch of their Christology is essential to our purpose. I. All material substance was regarded as evil. -

The Apocryphal and Legendary Life of Christ

Full text of "The Apocryphal and legendary life of Christ; being the whole body of the Apocryphal gospels and other extra canonical literature which pretends to tell of the life and words of Jesus Christ, including much matter which has not before appeared in English. In continuous narrative form, with notes, Scriptural references, prolegomena, and indices" View the book: http://archive.org/details/theapocryphaland00doneuoft THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST "H. & 5." DOLLAR LIBRARY Similar to this Volume THE TRAINING OF THE TWELVE. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE PARABOLIC TEACHING OF CHRIST. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE MIRACULOUS ELEMENT IN THE GOS PELS. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE HUMILIATION OF CHRIST. By Prof. A. B. Bruce, D.D. THE LIFE OF HENRY DRUMMOND. By Principal George Adam Smith. GESTA CHRISTI. By Charles Loring Brace. THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST. By J. DeQuincy Donehoo. INDIA: ITS LIFE AND THOUGHT. By John P. Jones, D.D. THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE CHRISTIAN RE LIGION. By Principal A. M. Fairbairn. PULPIT PRAYERS. By Alexander Maclaren, D.D. LECTURES ON THE HISTORY OF PREACH ING. By John Ker, D.D. RELIGIONS OF AUTHORITY AND THE RELI GION OF THE SPIRIT. By Auguste Sabatier. THE LIFE OF CHRIST AS REPRESENTED IN ART. By Dean Frederick W. Farrar. THE APOCRYPHAL AND LEGENDARY LIFE OF CHRIST BEING THE WHOLE BODY OF THE APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS AND OTHER EXTRA CANONICAL LITERATURE WHICH PRETENDS TO TELL OF THE LIFE AND WORDS OF JESUS CHRIST, INCLUDING MUCH MATTER WHICH HAS NOT BEFORE APPEARED IN ENGLISH.