Gram-Positive Bacteria Are Held at a Distance in the Colon Mucus by the Lectin-Like Protein ZG16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prokaryotes (Domains Bacteria & Archaea)

2/4/15 Prokaryotes (Domains Bacteria & Archaea) KEY POINTS 1. Decomposers: recycle organic and inorganic molecules in environment; makes them available to other organisms. 2. Essential components of symbioses. 3. Encompasses the origins of metabolism and metabolic diversity. 4. Origin of photosynthesis and formation of atmospheric Oxygen Ceno- Meso- zoic zoic ANTIQUITY Humans Paleozoic Colonization of land Animals Origin of solar system and Earth • >3.5 BILLION years old. • Alone for 2 1 4 billion years Proterozoic Archaean Prokaryotes Billions of 2 years ago3 Multicellular eukaryotes Single-celled eukaryotes Atmospheric oxygen General characteristics 1. Small: compare to 10-100µm for 0.5-5µm eukaryotic cell; single-celled; may form colonies. 2. Lack membrane- enclosed organelles. 3. Cell wall present, but different from plant cell wall. 1 2/4/15 General characteristics 4. Occur everywhere, most numerous organisms. – More individuals in a handful of soil then there are people that have ever lived. – By far more individuals in our gut than eukaryotic cells that are actually us. General characteristics 5. Metabolic diversity established nutritional modes of eukaryotes. General characteristics 6. Important decomposers and recyclers 2 2/4/15 General characteristics 6. Important decomposers and recyclers • Form the basis of global nutrient cycles. General characteristics 7. Symbionts!!!!!!! • Parasites • Pathogenic organisms. • About 1/2 of all human diseases are caused by Bacteria General characteristics 7. Symbionts!!!!!!! • Parasites • Pathogenic organisms. • Extremely important in agriculture as well. Pierce’s disease is caused by Xylella fastidiosa, a Gamma Proteobacteria. It causes over $56 million in damage annually in California. That’s with $34 million spent to control it! = $90 million in California alone. -

A Generic Large-Scale Cause for Platelet Dysfunction and Depletion in Infection

Published online: 2020-04-12 THIEME 302 A Champion of Host Defense: A Generic Large-Scale Cause for Platelet Dysfunction and Depletion in Infection Martin J. Page, BSc (Hons)1 Etheresia Pretorius, PhD1 1 Department of Physiological Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Address for correspondence Etheresia Pretorius, PhD, Department of Stellenbosch, South Africa Physiological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Stellenbosch University, Private Bag X1 Matieland, Stellenbosch, 7602, South Africa Semin Thromb Hemost 2020;46:302–319. (e-mail: [email protected]). Abstract Thrombocytopenia is commonly associated with sepsis and infections, which in turn are characterized by a profound immune reaction to the invading pathogen. Platelets are one of the cellular entities that exert considerable immune, antibacterial, and antiviral actions, and are therefore active participants in the host response. Platelets are sensitive to surrounding inflammatory stimuli and contribute to the immune response by multiple mechanisms, including endowing the endothelium with a proinflammatory phenotype, enhancing and amplifying leukocyte recruitment and inflammation, promoting the effector functions of immune cells, and ensuring an optimal adaptive immune response. During infection, pathogens and their products influence the platelet response and can even be toxic. However, platelets are able to sense and engage bacteria and viruses to assist in their removal and destruction. Platelets greatly contribute to host defense by multiple mechanisms, including forming immune complexes and aggregates, shedding their granular content, and internalizing pathogens and subsequently being marked for removal. These processes, and the nature of platelet function in general, cause the platelet to be irreversibly consumed in Keywords the execution of its duty. An exaggerated systemic inflammatory response to infection ► platelets can drive platelet dysfunction, where platelets are inappropriately activated and face ► virus immunological destruction. -

Killing of Gram-Negative Bacteria by Lactoferrin and Lysozyme

Killing of gram-negative bacteria by lactoferrin and lysozyme. R T Ellison 3rd, T J Giehl J Clin Invest. 1991;88(4):1080-1091. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI115407. Research Article Although lactoferrin has antimicrobial activity, its mechanism of action is not full defined. Recently we have shown that the protein alters the Gram-negative outer membrane. As this membrane protects Gram-negative cells from lysozyme, we have studied whether lactoferrin's membrane effect could enhance the antibacterial activity of lysozyme. We have found that while each protein alone is bacteriostatic, together they can be bactericidal for strains of V. cholerae, S. typhimurium, and E. coli. The bactericidal effect is dose dependent, blocked by iron saturation of lactoferrin, and inhibited by high calcium levels, although lactoferrin does not chelate calcium. Using differing media, the effect of lactoferrin and lysozyme can be partially or completely inhibited; the degree of inhibition correlating with media osmolarity. Transmission electron microscopy shows that E. coli cells exposed to lactoferrin and lysozyme at 40 mOsm become enlarged and hypodense, suggesting killing through osmotic damage. Dialysis chamber studies indicate that bacterial killing requires direct contact with lactoferrin, and work with purified LPS suggests that this relates to direct LPS-binding by the protein. As lactoferrin and lysozyme are present together in high levels in mucosal secretions and neutrophil granules, it is probable that their interaction contributes to host defense. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/115407/pdf Killing of Gram-negative Bacteria by Lactofernn and Lysozyme Richard T. Ellison III*" and Theodore J. Giehl *Medical and tResearch Services, Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and Division ofInfectious Diseases, Department ofMedicine, University ofColorado School ofMedicine, Denver, Colorado 80220 Abstract (4). -

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

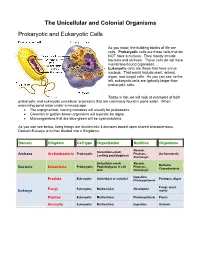

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Structural Basis of Mammalian Mucin Processing by the Human Gut O

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18696-y OPEN Structural basis of mammalian mucin processing by the human gut O-glycopeptidase OgpA from Akkermansia muciniphila ✉ ✉ Beatriz Trastoy 1,4, Andreas Naegeli2,4, Itxaso Anso 1,4, Jonathan Sjögren 2 & Marcelo E. Guerin 1,3 Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucin-degrading bacterium commonly found in the human gut that promotes a beneficial effect on health, likely based on the regulation of mucus thickness 1234567890():,; and gut barrier integrity, but also on the modulation of the immune system. In this work, we focus in OgpA from A. muciniphila,anO-glycopeptidase that exclusively hydrolyzes the peptide bond N-terminal to serine or threonine residues substituted with an O-glycan. We determine the high-resolution X-ray crystal structures of the unliganded form of OgpA, the complex with the glycodrosocin O-glycopeptide substrate and its product, providing a comprehensive set of snapshots of the enzyme along the catalytic cycle. In combination with O-glycopeptide chemistry, enzyme kinetics, and computational methods we unveil the molecular mechanism of O-glycan recognition and specificity for OgpA. The data also con- tribute to understanding how A. muciniphila processes mucins in the gut, as well as analysis of post-translational O-glycosylation events in proteins. 1 Structural Biology Unit, Center for Cooperative Research in Biosciences (CIC bioGUNE), Basque Research and Technology Alliance (BRTA), Bizkaia Technology Park, Building 801A, 48160 Derio, Spain. 2 Genovis AB, Box 790, 22007 Lund, Sweden. 3 IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation for Science, 48013 ✉ Bilbao, Spain. 4These authors contributed equally: Beatriz Trastoy, Andreas Naegeli, Itxaso Anso. -

Functional Anatomy of Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY OF PROKARYOTES AND EUKARYOTES BY DR JAWAD NAZIR ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF VETERINARY AND ANIMAL SCIENCES, LAHORE Prokaryotes vs Eukaryotes Prokaryote comes from the Greek words for pre-nucleus Eukaryote comes from the Greek words for true nucleus. Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Prokaryotes vs Eukaryotes Prokaryotes Eukaryotes One circular chromosome, not in Paired chromosomes, in nuclear a membrane membrane No histones Histones No organelles Organelles Peptidoglycan cell walls Polysaccharide cell walls Binary fission Mitotic spindle Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Size and shape Average size: 0.2 -1.0 µm 2 - 8 µm Basic shapes: Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Size and shape Pairs: diplococci, diplobacilli Clusters: staphylococci Chains: streptococci, streptobacilli Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Size and shape Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Size and shape Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Size and shape Unusual shapes Star-shaped Stella Square Haloarcula Most bacteria are monomorphic A few are pleomorphic Genus: Stella Genus: Haloarcula Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Bacterial cell structure Structures external to cell wall Cell wall itself Structures internal to cell wall Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Glycocalyx Outside cell wall Usually sticky A capsule is neatly organized A slime layer is unorganized & loose Extracellular polysaccharide allows cell to attach Capsules prevent phagocytosis Association with diseases B. anthracis S. pneumoniae Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Flagella Outside cell wall Filament made of chains of flagellin Attached to a protein hook Anchored to the wall and membrane by the basal body Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Flagella Arrangement Functional anatomy of prokaryotes Bacterial motility Rotate flagella to run or tumble Move toward or away from stimuli (taxis) Flagella proteins are H antigens (e.g., E. -

Protracted Anemia Associated with Chronic, Relapsing Systemic Inflammation Induced by Arthropathic Peptidoglycan-Polysaccharide Polymers in Rats R

INFECTION AND IMMUNITY, Apr. 1989, p. 1177-1185 Vol. 57, No. 4 0019-9567/89/041177-09$02.00/0 Copyright © 1989, American Society for Microbiology Protracted Anemia Associated with Chronic, Relapsing Systemic Inflammation Induced by Arthropathic Peptidoglycan-Polysaccharide Polymers in Rats R. BALFOUR SARTOR,l.2* SONIA K. ANDERLE,3 NADER RIFAI,4 DAVID A. T. GOO,4 WILLIAM J. CROMARTIE,3 AND JOHN H. SCHWAB2'3 Department of Medicine,1 Department of Microbiology and Immunology,3 Department ofPathology,4 and Core Center for Diarrheal Disease,2 University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7080 Received 3 October 1988/Accepted 6 January 1989 Mild hypoproliferative anemia with abnormal iron metabolism frequently accompanies chronic inflamma- tion and infection in humans. To determine whether anemia is associated with chronic relapsing arthritis induced by bacterial cell wall polymers, serial determinations of the hematocrit were measured in rats injected intraperitoneally with sonicated peptidoglycan-polysaccharide fragments from group A streptococci. Acute anemia peaked 5 to 10 days after injection, and chronic, spontaneously relapsing anemia persisted for 309 days. 51Cr labeling demonstrated decreased erythrocyte survival, i.e., a half-life of 8.4 days in cell wall-injected rats versus 11.8 days in controls. Erythrocytes were mildly microcytic, and leukocyte counts were elevated during early spontaneous reactivation of arthritis, 15 days after injection of peptidoglycan-polysaccharide. Bone marrow myeloid/erythroid precursor ratios were elevated in arthritic rats (P < 0.0001). Purified peptidoglycan produced an acute anemia lasting 10 days, while injection of group A streptococcal polysaccharide and mutanolysin-digested cell wall did not affect the hematocrit. -

Elucidating Peptidoglycan Structure: an Analytical Toolset

Trends in Microbiology Review Elucidating Peptidoglycan Structure: An Analytical Toolset Sara Porfírio,1 Russell W. Carlson,1 and Parastoo Azadi1,* Peptidoglycan (PG) is a ubiquitous structural polysaccharide of the bacterial cell Highlights wall, essential in preserving cell integrity by withstanding turgor pressure. Any PG is a major bacterial cell wall compo- change that affects its biosynthesis or degradation will disturb cell viability, nent, crucial for cell integrity, and strongly therefore PG is one of the main targets of antimicrobial drugs. Considering its related to antibiotic sensitivity. major role in cell structure and integrity, the study of PG is of utmost relevance, Methods to analyze PG structure have with prospective ramifications to several disciplines such as microbiology, phar- evolved over time, and new and im- macology, agriculture, and pathogenesis. Traditionally, high-performance liquid proved methods are currently replacing chromatography (HPLC) has been the workhorse of PG analysis. In recent years, previous tedious and long procedures. technological and bioinformatic developments have upgraded this seminal Current tools, ranging from technique, making analysis more sensitive and efficient than ever before. Here chromatography–mass spectrometry we describe a set of analytical tools for the study of PG structure (from composi- methods to imaging techniques, allow tion to 3D architecture), identify the most recent trends, and discuss future characterizing PG from a structural and architectural perspective. challenges in the field. Peptidoglycan Structure and Diversity Peptidoglycan (PG) (also known as murein, from Latin ‘murus’, wall) is a major component of the bacterial cell wall [1] (Figure 1). Present in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [2], this polysaccharide forms a flexible, net-like structure that determines cell shape and provides mechanical strength and osmotic stability. -

Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Inhibits Erythropoietin-Induced Myelin Gene

Gyetvai et al. Molecular Medicine (2018) 24:51 Molecular Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-018-0052-3 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Leukemia inhibitory factor inhibits erythropoietin-induced myelin gene expression in oligodendrocytes Georgina Gyetvai, Cieron Roe, Lamia Heikal, Pietro Ghezzi* and Manuela Mengozzi Abstract Background: The pro-myelinating effects of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) and other cytokines of the gp130 family, including oncostatin M (OSM) and ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), have long been known, but controversial results have also been reported. We recently overexpressed erythropoietin receptor (EPOR) in rat central glia-4 (CG4) oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) to study the mechanisms mediating the pro-myelinating effects of erythropoietin (EPO). In this study, we investigated the effect of co-treatment with EPO and LIF. Methods: Gene expression in undifferentiated and differentiating CG4 cells in response to EPO and LIF was analysed by DNA microarrays and by RT-qPCR. Experiments were performed in biological replicates of N ≥ 4. Functional annotation and biological term enrichment was performed using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery). The gene-gene interaction network was visualised using STRING (Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes). Results: In CG4 cells treated with 10 ng/ml of EPO and 10 ng/ml of LIF, EPO-induced myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) expression, measured at day 3 of differentiation, was inhibited ≥4-fold (N =5,P < 0.001). Inhibition of EPO-induced MOG was also observed with OSM and CNTF. Analysis of the gene expression profile of CG4 differentiating cells treated for 20 h with EPO and LIF revealed LIF inhibition of EPO-induced genes involved in lipid transport and metabolism, previously identified as positive regulators of myelination in this system. -

NOMENCLATURE of GLYCOPROTEINS, GLYCOPEPTIDES and PEPTIDOGLYCANS (Recommendations 1985)

Pure & Appl. Chern., Vol. 60, No. 9, pp. 1389-1394, 1988. Printed in Great Britain. INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF BIOCHEMISTRY JOINT COMMISSION ON BIOCHEMICAL NOMENCLATURE* NOMENCLATURE OF GLYCOPROTEINS, GLYCOPEPTIDES AND PEPTIDOGLYCANS (Recommendations 1985) Prepared for publication by N. SHARON The Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel *Membership of the Commission during the preparation of this report (1983-1987) was as follows: Chairman: H. B. F. Dixon (UK); Secretary: A. Cornish-Bowden (UK); Members: C. Li6becq (Belgium, representing the IUB Committee of Editors of Biochemical Journals); K. L. Loening (USA); G. P. Moss (UK); J. Reedijk (Netherlands); S. F. Velick (USA); P. Venetianer (Hungary); J. F. G. Vliegenthart (Netherlands). Additional contributors to the formulation of these recommendations: Nomenclature Committee of ZUB (NC-ZUB) (those additional to JCBN): H. Bielka (GDR); C. R. Cantor (USA); P. Karlson (FRG); N. Sharon (Israel); E. J. Van Lenten (USA); E. C. Webb (Australia). List of Reviewers: C. E. Ballou; E. Buddecke; E. A. Davidson; R. J. Doyle; D. Duksin; J.-M. Ghuysen; T. Hardingham; V. C. Hascall; D. HeinegArd; F. W. Hemming; D. Horton; R. C. Hughes; W. B. Jakoby; R. W. Jeanloz; 0. Kandler; T. Laurent; Y. C. Lee; U. Lindahl; B. Lindberg; H. Lis; F. G. Loontiens; J. Montreuil; H. Muir; A. Neuberger; E. F. Neufeld; T. Osawa; L. Roden; H. Schachter; R. Schauer; K. Schmid; G. D. Shockman; J. E. Silbert; C. C. Sweeley and I. Yamashina. Correspondence on these recommendations should be addressed to the Secretary of the Commission, Dr. A. Cornish-Bowden, CNRS-CBM, 31 chemin Joseph-Aiguier, B.P. -

Drosophila Genes Potentially Involved in Responses to Microbial Infection

gene in red: gene with a real "Immunity" signature or strongly induced (>3) or a function related to resistance to pathogens gene * Genes found in several places Drosophila genes potentially involved in responses to microbial infection Last update : June 2013 Expression pattern (Degregorio 2001,2002) name Flybase link Symbol homology and biology Septic injury B.bassiana Key references (for useful tools with an emphasis on mutations) I. Family of receptors that could be involved Microbial recognition (classified by gene family) CD36/croquemort (crq) family : 9 members croquemort CG4280 crq Genetic and molecular evidence exists for crq involvement in the phagocytos- - Franc 1996; Franc 1999 CG31741 CG31741 CG31741 crq-like - - Santa-maria CG12789 santa-maria crq-like - - peste CG7228 pes Peste is required for entry of Mycobacterium fortuitum in S2 cells - - Philips 2005 CG7227 CG7227 CG7227 crq-like - - emp CG2727 emp epithelial membrane protein; expressed in various embryonic tissues - - CG3829 CG3829 CG3829 emp-like - - CG1887 CG1887 CG1887 emp-like - - Sensory neuron membrane protein 1 CG7000 Snmp1 more related to sensory neuron membrane protein- involved in pherormon se- - CG2736 CG2736 CG2736 weakly related to emp - - BcDNA CG10345 CG10345 weakly related to emp - - Peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) family : 13 members Peptidoglycan recognition protein SA CG11709 PGRP-SA secreted PGRP required for Toll activation by Gram-Positive bateria in flies 9.5 - Michel 2001 PGRP-SC2 CG14745 PGRP-SC2 PGRP with amidase activity-In vivo, may -

Reviewed by HLDA1

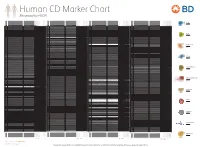

Human CD Marker Chart Reviewed by HLDA1 T Cell Key Markers CD3 CD4 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD8 CD1a R4, T6, Leu6, HTA1 b-2-Microglobulin, CD74 + + + – + – – – CD74 DHLAG, HLADG, Ia-g, li, invariant chain HLA-DR, CD44 + + + + + + CD158g KIR2DS5 + + CD248 TEM1, Endosialin, CD164L1, MGC119478, MGC119479 Collagen I/IV Fibronectin + ST6GAL1, MGC48859, SIAT1, ST6GALL, ST6N, ST6 b-Galactosamide a-2,6-sialyl- CD1b R1, T6m Leu6 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75 CD22 CD158h KIR2DS1, p50.1 HLA-C + + CD249 APA, gp160, EAP, ENPEP + + tranferase, Sialo-masked lactosamine, Carbohydrate of a2,6 sialyltransferase + – – + – – + – – CD1c M241, R7, T6, Leu6, BDCA1 b-2-Microglobulin + + + – + – – – CD75S a2,6 Sialylated lactosamine CD22 (proposed) + + – – + + – + + + CD158i KIR2DS4, p50.3 HLA-C + – + CD252 TNFSF4,