Matters of NATIONAL Environmental Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 by Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane

ARCHIVE: Known Impacts of Tropical Cyclones, East Coast, 1858 – 2008 By Mr Jeff Callaghan Retired Senior Severe Weather Forecaster, Bureau of Meteorology, Brisbane The date of the cyclone refers to the day of landfall or the day of the major impact if it is not a cyclone making landfall from the Coral Sea. The first number after the date is the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) for that month followed by the three month running mean of the SOI centred on that month. This is followed by information on the equatorial eastern Pacific sea surface temperatures where: W means a warm episode i.e. sea surface temperature (SST) was above normal; C means a cool episode and Av means average SST Date Impact January 1858 From the Sydney Morning Herald 26/2/1866: an article featuring a cruise inside the Barrier Reef describes an expedition’s stay at Green Island near Cairns. “The wind throughout our stay was principally from the south-east, but in January we had two or three hard blows from the N to NW with rain; one gale uprooted some of the trees and wrung the heads off others. The sea also rose one night very high, nearly covering the island, leaving but a small spot of about twenty feet square free of water.” Middle to late Feb A tropical cyclone (TC) brought damaging winds and seas to region between Rockhampton and 1863 Hervey Bay. Houses unroofed in several centres with many trees blown down. Ketch driven onto rocks near Rockhampton. Severe erosion along shores of Hervey Bay with 10 metres lost to sea along a 32 km stretch of the coast. -

Restricted Water Ski Areas in Queensland

Restricted Water Ski areas in Queensland Watercourse Date of Gazettal Any person operating a ship towing anyone by a line attached to the ship (including for example a person water skiing or riding on a toboggan or tube) within the waters listed below endangers marine safety. Brisbane River 20/10/2006 South Brisbane and Town Reaches of the Brisbane River between the Merivale Bridge and the Story Bridge. Burdekin River, Charters Towers 13/09/2019 All waters of The Weir on the Burdekin River, Charters Towers. Except: • commencing at a point on the waterline of the eastern bank of the Burdekin River nearest to location 19°55.279’S, 146°16.639’E, • then generally southerly along the waterline of the eastern bank to a point nearest to location 19°56.530’S, 146°17.276’E, • then westerly across Burdekin River to a point on the waterline of the western bank nearest to location 19°56.600’S, 146°17.164’E, • then generally northerly along the waterline of the western bank to a point on the waterline nearest to location 19°55.280’S, 146°16.525’E, • then easterly across the Burdekin River to the point of commencement. As shown on the map S8sp-73 prepared by Maritime Safety Queensland (MSQ) which can be found on the MSQ website at www.msq.qld.gov.au/s8sp73map and is held at MSQ’s Townsville Office. Burrum River .12/07/1996 The waters of the Burrum River within 200 metres north from the High Water mark of the southern river bank and commencing at a point 50 metres downstream of the public boat ramp off Burrum Heads Road to a point 200 metres upstream of the upstream boundary of Lions Park, Burrum Heads. -

Beacon to Beacon Guide: Noosa River

Maritime Safety Queensland Noosa River Boat Ramp, Tewantin Beacon to Beacon Guide Noosa River Published by For commercial use terms and conditions Maritime Safety Queensland Please visit the Maritime Safety Queensland website at www.msq.qld.gov.au © Copyright The State of Queensland (Department of Transport and Main Roads) 2021 ‘How to’ use this guide Use this Beacon to Beacon Guide with To view a copy of this licence, visit the ‘How to’ and legend booklet available from https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ www.msq.qld.gov.au Noosa River Cooloola Beach Key Sheet Next series NOOSA Great Sandy Strait RIVER Marine rescue services 10 CG Noosa Enlargements A Boreen Point B Noosa Marina Lake Cooloola Shark control apparatus Lake exclusion zones Como Exclusion zones exist for waters within 20 metres of any shark control apparatus. It is an offence (fines may apply) to be in an exclusion zone if not transiting directly through. For further information see the Department of Agriculture and Fisheries website at www.daf.qld.gov.au. Teewah Beach Depth contour date information Elanda Point Depth contours shown on the maps within this guide were surveyed by Maritime Safety Queensland 2000-2016. Kin Kin Some 0m contours have been approximated from recent Lake Teewah Cootharaba TMR air photography. A Boreen Point SOUTH CORAL NOOSA SEA RIVER PACIFIC Lake Cooroibah Six Mile Creek Dam Noosa Head TEWANTIN 10 Lake 10 Macdonald B NOOSA HEADS OCEAN Sunshine Cooroy Beach For maps and information on the Noosa River marine zones please visit Maritime Safety Queensland website (www.msq.qld.gov.au) under the Waterways tab and click on Marine Zones. -

Restoration of Noosa Estuary

Ecological Service Professionals Sustainable Science Solutions Restoration of Noosa Estuary An Assessment of Oyster Recruitment Prepared by The Nature Conservancy & Ecological Service Professionals July 2015 Document Control Report Title: Restoration of Noosa Estuary: An Assessment of Oyster Recruitment Provider: The Nature Conservancy Contact: Edward Game [email protected] Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without financial assistance from Noosa Shire Council and The Thomas Foundation. Important support was also provided by the Noosa Parks Association, in particular, we thank Brian Walsh who provided his vessel, skippered us safely around the estuary and provided such great company and assistance each day we ventured out in the field. The Walkers provided use of their jetty in Noosa Sound to suspend tiles, which was greatly appreciated. Executive Summary With the support of the Noosa Shire Council and The Thomas Foundation, The Nature Conservancy undertook an assessment of oyster recruitment in the Noosa Estuary. This assessment is a critical piece of information to inform the viability and design or future oyster reef restoration projects in the estuary. This report presents the findings of the assessment, which involved deploying over 160 settlement tiles (10 cm x 10 cm squares made from fibrous cement sheet) for periods of up to 5 months between December 2014 and June 2015. Settlement tiles were deployed at seven intertidal (0.1 m above low water mark) and five subtidal sites (typically 1 m below the surface) around the Noosa River Estuary. Key findings from the analysis of these settlement tiles are: Oysters recruited in moderate numbers at nearly all sites, with the highest observed recruitment occurring in Weyba Creek, the main channel around Tewantin, and in the narrow channel between Goat Island and Noosa North Shore. -

Citizens & Reef Science

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Report Editor: Jennifer Loder Report Authors and Contributors: Jennifer Loder, Terry Done, Alex Lea, Annie Bauer, Jodi Salmond, Jos Hill, Lionel Galway, Eva Kovacs, Jo Roberts, Melissa Walker, Shannon Mooney, Alena Pribyl, Marie-Lise Schläppy Science Advisory Team: Dr. Terry Done, Dr. Chris Roelfsema, Dr. Gregor Hodgson, Dr. Marie-Lise Schläppy, Jos Hill Graphic Designers: Manu Taboada, Tyler Hood, Alex Levonis This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this licence visit: http:// This project is supported by Reef Check creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Australia, through funding from the Australian Government. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Reef Check Foundation Ltd, PO Box 13204 George St Brisbane QLD 4003, Project achievements have been made [email protected] possible by a countless number of dedicated volunteers, collaborators, funders, advisors and industry champions. Citation: Thanks from us and our oceans. Volunteers, Staff and Supporters of Reef Check Australia (2015). Authors J. Loder, T. Done, A. Lea, A. Bauer, J. Salmond, J. Hill, L. Galway, E. Kovacs, J. Roberts, M. Walker, S. Mooney, A. Pribyl, M.L. Schläppy. Citizens & Reef Science: A Celebration of Reef Check Australia’s volunteer reef monitoring, education and conservation programs 2001- 2014. Reef Check Foundation Ltd. Cover photo credit: Undersea Explorer, GBR Photo by Matt Curnock (Russell Island, GBR) 3 Key messages FROM REEF CHECK AUSTRALIA 2001-2014 WELCOME AND THANKS • Reef monitoring is critical to understand • Across most RCA sites there was both human and natural impacts, as well evidence of reef health impacts. -

Land Cover Change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management Region 2010–11

Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts Land cover change in the South East Queensland Catchments Natural Resource Management region 2010–11 Summary The woody vegetation clearing rate for the SEQ region for 10 2010–11 dropped to 3193 hectares per year (ha/yr). This 9 8 represented a 14 per cent decline from the previous era. ha/year) 7 Clearing rates of remnant woody vegetation decreased in 6 5 2010-11 to 758 ha/yr, 33 per cent lower than the previous era. 4 The replacement land cover class of forestry increased by 3 2 a further 5 per cent over the previous era and represented 1 Clearing Rate (,000 26 per cent of the total woody vegetation 0 clearing rate in the region. Pasture 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 remained the dominant replacement All Woody Clearing Woody Remnant Clearing land cover class at 34 per cent of total clearing. Figure 1. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Figure 2. Woody vegetation clearing for each change period. Great state. Great opportunity. Woody vegetation clearing by Woody vegetation clearing by remnant status tenure Table 1. Remnant and non-remnant woody vegetation clearing Table 2. Woody vegetation clearing rates in the South East rates in the South East Queensland Catchments NRM region. Queensland Catchments NRM region by tenure. Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) of Woody vegetation clearing rate (,000 ha/yr) on Non-remnant Remnant -

22Nd March 2019

This booklet has been prepared to commemorate the historic 200th General Meeting of the Mary River Catchment Coordinating Committee on Friday 22nd of March 2019 at Garapine; the location of the inaugural meeting in November 1993. It adds to a previous booklet prepared for the 100th meeting which was held at the Gympie Civic Centre on Wednesday 16th February 2005. For almost 25 years, the MRCCC has forged productive partnerships with thousands of stakeholders throughout the Mary River catchment and beyond; government at all three levels, industry, farmers, large and small rural and urban landholders, landcare and environment groups, recreational and commercial fishing interests, forestry, irrigators, Waterwatch volunteers, researchers, school students, and particularly the long-running working partnership with the Gympie District Beef Liaison Group. These partnerships have triggered a phenomenal groundswell of interest and activities in natural resource management across the Mary River catchment. The wider community is beginning to understand many of the causes of environmental degradation. The farming community is embracing sustainable production as a means of increasing productivity whilst protecting natural assets. Governments at all levels now recognise that community engagement is critical to environmental repair and ecological protection. Triple bottom line objectives are now commonplace in strategic planning documents. So what were the factors that led to the need for an “across the board” shift in philosophy? In the 1990’s, the Mary River was described as one of the most degraded catchments in Queensland. European settlement resulted in extensive clearing of the riverbanks. In recent times, massive land use change due to subdivision, population pressure and other factors together with increasing demand for water resources led to deteriorating catchment condition. -

Fisheries Guidelines for Design of Stream Crossings

Fish Habitat Guideline FHG 001 FISH PASSAGE IN STREAMS Fisheries guidelines for design of stream crossings Elizabeth Cotterell August 1998 Fisheries Group DPI ISSN 1441-1652 Agdex 486/042 FHG 001 First published August 1998 Information contained in this publication is provided as general advice only. For application to specific circumstances, professional advice should be sought. The Queensland Department of Primary Industries has taken all reasonable steps to ensure the information contained in this publication is accurate at the time of publication. Readers should ensure that they make appropriate enquiries to determine whether new information is available on the particular subject matter. © The State of Queensland, Department of Primary Industries 1998 Copyright protects this publication. Except for purposes permitted by the Copyright Act, reproduction by whatever means is prohibited without the prior written permission of the Department of Primary Industries, Queensland. Enquiries should be addressed to: Manager Publishing Services Queensland Department of Primary Industries GPO Box 46 Brisbane QLD 4001 Fisheries Guidelines for Design of Stream Crossings BACKGROUND Introduction Fish move widely in rivers and creeks throughout Queensland and Australia. Fish movement is usually associated with reproduction, feeding, escaping predators or dispersing to new habitats. This occurs between marine and freshwater habitats, and wholly within freshwater. Obstacles to this movement, such as stream crossings, can severely deplete fish populations, including recreational and commercial species such as barramundi, mullet, Mary River cod, silver perch, golden perch, sooty grunter and Australian bass. Many Queensland streams are ephemeral (they may flow only during the wet season), and therefore crossings must be designed for both flood and drought conditions. -

Feedback on Draft Noosa River Plan Version 1

General Committee Agenda 18 January 2021 Attachment 2 to Item 2 – Consultation Report River Plan Version 1 (2018) Feedback on Draft Noosa River Plan version 1 The information below provides a collation of detailed feedback on the Draft Noosa River Plan received from the community during the public consultation period from 20 July to 26 August 2018. This feedback consists of responses to the Noosa River Plan SURVEY published on Council’s Your Say Noosa (YSN) website, and written submissions received from individuals and organisations. Three questions were posed in the SURVEY: 1. What do you think will be most important in maintaining and improving the quality of the Noosa River system? 2. Are there any actions to consider for inclusion in the Draft Noosa River Plan? 3. The cost of implementing the actions recommended in the Draft Noosa River Plan is estimated to be $2.23M over 5 years (i.e. $446,000 pa). Are you willing to pay extra (via General Rates or Environment Levy and/or Tourism and Economic Levy) for Noosa Council to fully implement the River Plan so that the Noosa River has a better chance of remaining a pristine and vital community asset? If yes, how much per year ($5, $10, $15, $20)? Summary of feedback The top four (4) priorities deemed most important to maintain and improve the quality of the Noosa River system were identified as: • managing pollution and litter running into the river • protecting wetlands, riparian and coastal areas • reducing sediment from upstream entering the river • controlling recreational use of the -

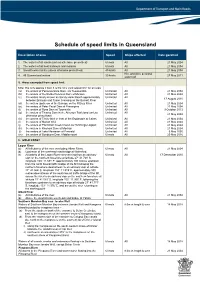

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Report on the Administration of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Reporting Period 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020)

Report on the administration of the Nature Conservation Act 1992 (reporting period 1 July 2019 to 30 June 2020) Prepared by: Department of Environment and Science © State of Queensland, 2020. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. September 2020 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Nature Conservation Act 1992—departmental administrative responsibilities ............................................................. 1 List of legislation and subordinate legislation .............................................................................................................. -

2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan: Redlands

Item: Redlands Draft LG Report Date: Last updated 11th November 2014 2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan: Redlands How can the SEQ NRM Plan support the Community’s Vision for the future of Redlands? Supporting Document no. 7 for the 2014 Update of the SEQ Natural Resource Management Plan. Note regards State Government Planning Policy: The Queensland Government is currently undertaking a review of the SEQ Regional Plan 2009. Whilst this review has yet to be finalised, the government has made it clear that the “new generation” statutory regional plans focus on the particular State Planning Policy issues that require a regionally-specific policy direction for each region. This quite focused approach to statutory regional plans compares to the broader content in previous (and the current) SEQ Regional Plan. The SEQ Natural Resource Management Plan has therefore been prepared to be consistent with the State Planning Policy. Disclaimer: This information or data is provided by SEQ Catchments Limited on behalf of the Project Reference Group for the 2014 Update of the SEQ NRM Plan. You should seek specific or appropriate advice in relation to this information or data before taking any action based on its contents. So far as permitted by law, SEQ Catchments Limited makes no warranty in relation to this information or data. ii Table of Contents Redlands, Bay and Islands ....................................................................................................................... 1 Part A - Achieving the community’s visions for Redlands .................................................................... 1 Queensland Plan – South East Queensland Themes .......................................................................... 1 Regional Development Australia - Logan and Redlands ..................................................................... 1 Services needed from natural assets to achieve these Visions .......................................................... 2 Natural Assets depend on the biodiversity of the Redlands.