ATT – Background Paper: Scope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CRUISE MISSILE THREAT Volume 2: Emerging Cruise Missile Threat

By Systems Assessment Group NDIA Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense Committee August 1999 FEASIBILITY OF THIRD WORLD ADVANCED BALLISTIC AND CRUISE MISSILE THREAT Volume 2: Emerging Cruise Missile Threat The Systems Assessment Group of the National Defense Industrial Association ( NDIA) Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense Committee performed this study as a continuing examination of feasible Third World missile threats. Volume 1 provided an assessment of the feasibility of the long range ballistic missile threats (released by NDIA in October 1998). Volume 2 uses aerospace industry judgments and experience to assess Third World cruise missile acquisition and development that is “emerging” as a real capability now. The analyses performed by industry under the broad title of “Feasibility of Third World Advanced Ballistic & Cruise Missile Threat” incorporate information only from unclassified sources. Commercial GPS navigation instruments, compact avionics, flight programming software, and powerful, light-weight jet propulsion systems provide the tools needed for a Third World country to upgrade short-range anti-ship cruise missiles or to produce new land-attack cruise missiles (LACMs) today. This study focuses on the question of feasibility of likely production methods rather than relying on traditional intelligence based primarily upon observed data. Published evidence of technology and weapons exports bears witness to the failure of international agreements to curtail cruise missile proliferation. The study recognizes the role LACMs developed by Third World countries will play in conjunction with other new weapons, for regional force projection. LACMs are an “emerging” threat with immediate and dire implications for U.S. freedom of action in many regions . -

Desind Finding

NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ARCHIVES Herbert Stephen Desind Collection Accession No. 1997-0014 NASM 9A00657 National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC Brian D. Nicklas © Smithsonian Institution, 2003 NASM Archives Desind Collection 1997-0014 Herbert Stephen Desind Collection 109 Cubic Feet, 305 Boxes Biographical Note Herbert Stephen Desind was a Washington, DC area native born on January 15, 1945, raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and educated at the University of Maryland. He obtained his BA degree in Communications at Maryland in 1967, and began working in the local public schools as a science teacher. At the time of his death, in October 1992, he was a high school teacher and a freelance writer/lecturer on spaceflight. Desind also was an avid model rocketeer, specializing in using the Estes Cineroc, a model rocket with an 8mm movie camera mounted in the nose. To many members of the National Association of Rocketry (NAR), he was known as “Mr. Cineroc.” His extensive requests worldwide for information and photographs of rocketry programs even led to a visit from FBI agents who asked him about the nature of his activities. Mr. Desind used the collection to support his writings in NAR publications, and his building scale model rockets for NAR competitions. Desind also used the material in the classroom, and in promoting model rocket clubs to foster an interest in spaceflight among his students. Desind entered the NASA Teacher in Space program in 1985, but it is not clear how far along his submission rose in the selection process. He was not a semi-finalist, although he had a strong application. -

OPERATION CORPORATE Taken from the PWO's Diary at the Time On

OPERATION CORPORATE Taken from the PWO’s Diary at the time on HMS GLAMORGAN (transcribed by Danny Wort ex RS) 1982 2 April Argentine troops invade Falkland Islands. Garrison of about 80 marines put up a good fight killing and wounding Argies in a fierce gun battle. Marines run out of ammo and told to put down arms by Commander. 1500 Argentine troops against 80 but what a fight. RAS(L) with BLUE ROVER – 158 tons 4 April South Georgia invaded marines from ENDURANCE put ashore, put up a good fight, fired anti-tank rockets at CORVETTE, seriously damaged it and brought down helicopter. We are on our way to the Ascension Islands. Big Task Force underway. RAS(L) TIDESPRING – 200 tons 5 April Britain mustering task force, Hermes and Invincible made ready, Cmdo Brigade and 1st parachute battalion embarked and with others. “Tally Ho! Here we come Argies” 6 April Fearless sails from U.K. We are moving South. RAS(L) TIDESPRING – 228 tons 10 April Arrive Ascension Islands much activity with Hercules bringing stores out from U.K. RAS(L) APPLELEAF – 200 tons 12 April Vertrep stores all day, food, ammo and Beer 13 April More work bringing on stores RAS(L) APPLELEAF – 212 tons 14 April Depart Ascension to R/V with Hermes. The Harriers look very impressive, hope they are good combat aircraft, though they are usually ground attack. 15 April Admiral Woodward to Hermes, flag in Command. Steam back to Ascension. 16 April Prep for war, much activity, stores accounting, black out ship 17 April Heading South with SHEFFIELD, ALACRITY, ARROW, BRILLIANT, GLASGOW and COVENTRY. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D European & Security ES & Defence 2/2018 International Security and Defence Journal COUNTRY FOCUS: MALAYSIA ISSN 1617-7983 • www.euro-sd.com • March 2018 Unmanned Maritime Systems Game Changer for EU Defence? Spain: Increasing Funds for Defence 25 member states established the ”Permanent Seven new programmes are to be scheduled Structured Cooperation“ (PESCO). for the next 15 years. Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology The backbone of every strong troop. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles. When your mission is clear. When there’s no road for miles around. And when you need to give all you’ve got, your equipment needs to be the best. At times like these, we’re right by your side. Mercedes-Benz Defence Vehicles: armoured, highly capable off-road and logistics vehicles with payloads ranging from 0.5 to 110 t. Mobilising safety and efficiency: www.mercedes-benz.com/defence-vehicles Editorial The Balkans Are Losing Their Illusions At the beginning of the year, Bulgaria strategy”. If this were true, the authors took over the presidency of the European would have performed a particularly great Council. The six months in which a Mem- service by giving the term a new content. ber State exercises this honorary position, So far, it has been assumed that a strategy before passing on the baton to the next indicates how a goal should be achieved. capital city, are too short for course- However, this document offers only vague setting. Certainly, at least for a moment, hints. Instead, it lists once again what the President of the Council can put issues requirements applicants must fulfil in or- that are important to him on the agenda. -

Worldwide Equipment Guide Volume 2: Air and Air Defense Systems

Dec Worldwide Equipment Guide 2016 Worldwide Equipment Guide Volume 2: Air and Air Defense Systems TRADOC G-2 ACE–Threats Integration Ft. Leavenworth, KS Distribution Statement: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 1 UNCLASSIFIED Worldwide Equipment Guide Opposing Force: Worldwide Equipment Guide Chapters Volume 2 Volume 2 Air and Air Defense Systems Volume 2 Signature Letter Volume 2 TOC and Introduction Volume 2 Tier Tables – Fixed Wing, Rotary Wing, UAVs, Air Defense Chapter 1 Fixed Wing Aviation Chapter 2 Rotary Wing Aviation Chapter 3 UAVs Chapter 4 Aviation Countermeasures, Upgrades, Emerging Technology Chapter 5 Unconventional and SPF Arial Systems Chapter 6 Theatre Missiles Chapter 7 Air Defense Systems 2 UNCLASSIFIED Worldwide Equipment Guide Units of Measure The following example symbols and abbreviations are used in this guide. Unit of Measure Parameter (°) degrees (of slope/gradient, elevation, traverse, etc.) GHz gigahertz—frequency (GHz = 1 billion hertz) hp horsepower (kWx1.341 = hp) Hz hertz—unit of frequency kg kilogram(s) (2.2 lb.) kg/cm2 kg per square centimeter—pressure km kilometer(s) km/h km per hour kt knot—speed. 1 kt = 1 nautical mile (nm) per hr. kW kilowatt(s) (1 kW = 1,000 watts) liters liters—liquid measurement (1 gal. = 3.785 liters) m meter(s)—if over 1 meter use meters; if under use mm m3 cubic meter(s) m3/hr cubic meters per hour—earth moving capacity m/hr meters per hour—operating speed (earth moving) MHz megahertz—frequency (MHz = 1 million hertz) mach mach + (factor) —aircraft velocity (average 1062 km/h) mil milliradian, radial measure (360° = 6400 mils, 6000 Russian) min minute(s) mm millimeter(s) m/s meters per second—velocity mt metric ton(s) (mt = 1,000 kg) nm nautical mile = 6076 ft (1.152 miles or 1.86 km) rd/min rounds per minute—rate of fire RHAe rolled homogeneous armor (equivalent) shp shaft horsepower—helicopter engines (kWx1.341 = shp) µm micron/micrometer—wavelength for lasers, etc. -

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb

Combat Search and Rescue in Desert Storm DARREL D. WHITCOMB Colonel, USAFR, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama September 2006 front.indd 1 11/6/06 3:37:09 PM Air University Library Cataloging Data Whitcomb, Darrel D., 1947- Combat search and rescue in Desert Storm / Darrel D. Whitcomb. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references. A rich heritage: the saga of Bengal 505 Alpha—The interim years—Desert Shield— Desert Storm week one—Desert Storm weeks two/three/four—Desert Storm week five—Desert Sabre week six. ISBN 1-58566-153-8 1. Persian Gulf War, 1991—Search and rescue operations. 2. Search and rescue operations—United States—History. 3. United States—Armed Forces—Search and rescue operations. I. Title. 956.704424 –– dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. © Copyright 2006 by Darrel D. Whitcomb ([email protected]). Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112-6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii front.indd 2 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM This work is dedicated to the memory of the brave crew of Bengal 15. Without question, without hesitation, eight soldiers went forth to rescue a downed countryman— only three returned. God bless those lost, as they rest in their eternal peace. front.indd 3 11/6/06 3:37:10 PM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . -

Battle Atlas of the Falklands War 1982

ACLARACION DE www.radarmalvinas.com.ar El presente escrito en PDF es transcripción de la versión para internet del libro BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea, and Air de GORDON SMITH, publicado por Ian Allan en 1989, y revisado en 2006 Usted puede acceder al mismo en el sitio www.naval-history.com Ha sido transcripto a PDF y colocado en el sitio del radar Malvinas al sólo efecto de preservarlo como documento histórico y asegurar su acceso en caso de que su archivo o su sitio no continúen en internet, ya que la información que contiene sobre los desplazamientos de los medios británicos y su cronología resultan sumamente útiles como información británica a confrontar al analizar lo expresado en los diferentes informes argentinos. A efectos de preservar los derechos de edición, se puede bajar y guardar para leerlo en pantalla como si fuera un libro prestado por una biblioteca, pero no se puede copiar, editar o imprimir. Copyright © Penarth: Naval–History.Net, 2006, International Journal of Naval History, 2008 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- BATTLE ATLAS OF THE FALKLANDS WAR 1982 NAVAL-HISTORY.NET GORDON SMITH BATTLE ATLAS of the FALKLANDS WAR 1982 by Land, Sea and Air by Gordon Smith HMS Plymouth, frigate (Courtesy MOD (Navy) PAG Introduction & Original Introduction & Note to 006 Based Notes Internet Page on the Reading notes & abbreviations 008 book People, places, events, forces 012 by Gordon Smith, Argentine 1. Falkland Islands 021 Invasion and British 2. Argentina 022 published by Ian Allan 1989 Response 3. History of Falklands dispute 023 4. South Georgia invasion 025 5. -

The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles

The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles Product Code #F658 A Special Focused Market Segment Analysis by: Missile Forecast Analysis 3 The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles 2010-2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................2 Introduction................................................................................................................................................................3 Trends..........................................................................................................................................................................5 Competitive Environment.......................................................................................................................................6 Market Statistics .......................................................................................................................................................9 Table 1 - The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles Unit Production by Headquarters/Company/Program 2010 - 2019 ................................................15 Table 2 - The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles Value Statistics by Headquarters/Company/Program 2010 - 2019.................................................20 Figure 1 - The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles Unit Production 2010 - 2019 (Bar Graph) ...............................................................................25 Figure 2 - The Market for Anti-Ship Missiles -

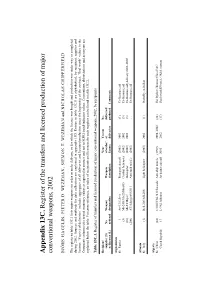

Appendix 13C. Register of the Transfers and Licensed Production of Major Conventional Weapons, 2002

Appendix 13C. Register of the transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002 BJÖRN HAGELIN, PIETER D. WEZEMAN, SIEMON T. WEZEMAN and NICHOLAS CHIPPERFIELD The register in table 13C.1 lists major weapons on order or under delivery, or for which the licence was bought and production was under way or completed during 2002. Sources and methods for data collection are explained in appendix 13D. Entries in table 13C.1 are alphabetical, by recipient, supplier and licenser. ‘Year(s) of deliveries’ includes aggregates of all deliveries and licensed production since the beginning of the contract. ‘Deal worth’ values in the Comments column refer to real monetary values as reported in sources and not to SIPRI trend-indicator values. Conventions, abbreviations and acronyms are explained below the table. For cross-reference, an index of recipients and licensees for each supplier can be found in table 13C.2. Table 13C.1. Register of transfers and licensed production of major conventional weapons, 2002, by recipients Recipient/ Year Year(s) No. supplier (S) No. Weapon Weapon of order/ of delivered/ or licenser (L) ordered designation description licence deliveries produced Comments Afghanistan S: Russia 1 An-12/Cub-A Transport aircraft (2002) 2002 (1) Ex-Russian; aid (5) Mi-24D/Mi-25/Hind-D Combat helicopter (2002) 2002 (5) Ex-Russian; aid (10) Mi-8T/Hip-C Helicopter (2002) 2002 (3) Ex-Russian; aid; delivery 2002–2003 (200) AT-4 Spigot/9M111 Anti-tank missile (2002) . Ex-Russian; aid Albania S: Italy (1) Bell-206/AB-206 Light helicopter -

Missile Total and Subsection Weight and Size Estimation Equations

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1992-06 Missile total and subsection weight and size estimation equations Nowell, John B., Jr. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/23959 DUDLEY KVOX LIBRARY NAVAL F . *AOUATE SCHOOL MONTERt. uA 9334A-J101 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Missile Total and Subsection Weight and Size Estimation Equations by John B. Nowell Jr. Lieutenant, United States Navy B.S., United States Naval Academy, 1984 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ENGINEERING SCIENCE from the NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL June 1992 Unclassified CURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB NO. 0704-01 88 i REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION lb RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS UNCLASSIFIED i SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3 DISTRIBUTION/ AVAILABILITY OF REPORT Approved for public release ; ) DECLASSIFICATION /DOWNGRADING SCHEDULE distribution is unlimited PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5 MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) i NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b OFFICE SYMBOL 7a NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION (If applicable) Naval Postgraduate School 033 Naval Postgraduate School :. ADDRESS {City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b ADDRESS {City, Stale, and ZIP Code) Monterey, CA 9394 3-5000 Monterey, CA 9 3943-5000 3 NAME OF FUNDING /SPONSORING 8b OFFICE SYMBOL 9 PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If applicable) : ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS PROGRAM PROJECT TASK WORK UNIT ELEMENT NO NO NO ACCESSION NO 1 TITLE (Include Security Classification) MISSILE TOTAL AND SUBSECTION WEIGHT AND SIZE ESTIMATION EQUATIONS 2 PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Nowell Jr., John B. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents August 2021 Overviews World Missiles, UAVs & Smart Munitions Market Overview ...........................................................January 2021 Air Defense Missile Market Overview ................................................................................................January 2021 Air-to-Air Missile Market Overview ...................................................................................................January 2021 Air-to-Surface Missile Market Overview ............................................................................................January 2021 Antiship Missile Market Overview .....................................................................................................January 2021 Antitank Missile Market Overview .....................................................................................................January 2021 Surface-to-Surface Missile Market Overview .....................................................................................January 2021 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Market Overview.....................................................................................January 2021 Air-to-Air Air-to-Air Missile Digest .................................................................................................................. February 2021 AIM-9 Sidewinder .................................................................................................................................... July 2021 AIM-9X ................................................................................................................................................... -

A European Armaments Policy

DOCUMENT 786 31st October 1978 ASSEMBLY OF WESTERN EUROPEAN UNION TWENTY-FOURTH ORDINARY SESSION (Second Part) A European armaments policy REPORT submitted on behalf of the Committee on Defence Questions and Armaments by Mr. Critchley, Rapporteur ASSEMBLY OF WESTERN EUROPEAN UNION 43, avenue du Prllsldent Wilson, 75n5 Paris Cedex 16 - Till. 723.54.32 Document 786 31st October 1978 A European armaments policy REPORT 1 submitted on behalf of the Committee on Defence Questions and Armaments 2 by Mr. Critchley, Rapporteur TABLE OF CONTENTS DRAFT RECOMMENDATION on a European armaments policy EXPLANATORY MEMORANDUM submitted by Mr. Critchley, Rapporteur I. Introduction II. The problems III. The approach tfr solutions IV. The international organisations A. The rOle of NATO B. The independent European programme group C. The role of WEU D. The Panavia Tornado - A case study in collaborative procurement V. The view from national capitals A. Belgium B. France C. Federal Republic of Germany D. Italy VI. Conclusions VII. Opinion of the minority APPENDICES : I. The ten action areas under the NATO long-term defence programme on which task forces have been established II. Structure of IEPG III. Future equipment programmes IV. Joint production - Collaborative projects as a proportion of national defence equipment procurement V. Procurement, research and development, and research as a percentage of defence budget 1. Adopted in Co=ittee by 7 votes to 6 with 3 Handlos, Hardy, Konen, de Koster, Lemmrich, Maggioni, abstentions. Menard, Pawelczyk (Alternate : Buchner), Pecchioli, Peronnet, Hermann Schmidt (Alternate: Vohrer), Schol 2. Members of the Committee : Mr. Roper (Chairman); ten, Tanghe, Whitehead (Alternate: Banks).