Trade Mark Inter Partes Decision 0/662/17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whiskey Specialty, 35% Alcohol by Volume (70 Proof)

MAY 2020 ALABAMA Select Spirits PUBLISHED BY American Wine & Spirits, LLC PO Box 380832 Birmingham, Al 35283 Dear Licensees: [email protected] This isn’t business as usual, and it’s a time of great stress and uncertainty. Across this CREATIVE DIRECTOR great state of ours, people are feeling the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pilar Taylor Some of you are faced with difficult and unpleasant choices in response to this crisis. Some are reducing operations, while some restaurants, bars and clubs are being forced to shut CONTRIBUTING WRITER their doors. The economic fallout is being felt across our communities. Norma Butterworth-McKittrick The ABC Board has been deemed an essential part of state government and much of the ADVERTISING & critical work we do cannot be done from home. Our employees are putting forth tremendous PRODUCTION MANAGER effort to make sure core services remain available. We’ve also implemented a series of Margriet Linthout preventative health measures for the safety of our employees and our customers. For more information about this publication, advertising rates, production specs, recipes I would like to thank our employees and ALL the essential workers throughout our state who and digital copies of recent and current are putting in long days and nights to ensure the supply chain stays open and to make sure issues visit americanwineandspirits.com or we have access to the necessities during an immensely challenging time. We know you are call 205-368-5740 doing crucial work, and we appreciate you. We couldn’t get through this without you. PHOTOGRAPHY It is the Board’s mission to provide the best service possible to our customers. -

1879-2013 Our Roots

1879-2013 OUR ROOTS Avda. Constitución, 106. facebook.com/vinosdelbierzosc 24540 Cacabelos. León. Spain twitter.com/vinosdelbierzo [Phone] +34 987 54 61 50 [Fax] +34 987 54 92 36 plus.google.com/102280348626339387124 www.vinosdelbierzo.com vimeo.com/channels/611420 [email protected] youtube.com/channel/UCrcNgBPjPM8qt76WYZGdRfQ OUR ROOTS 1879-2013 e story of the Guerra family and its boost to the wine industry in Bierzo has been mentioned by some historians, but with little details, apart from the notes of his distant cousin Raúl Guerra Garrido. e winery was founded in 1879, which is also the year of the release of the rst bottle of Guerra and therefore Vinos Guerra is one of the oldest wineries producing and selling bottled wine with one of the oldest brands of Spain. A real example of innovation with a wide range, not only of wines, but also of spirits and sparkling wines, importing and applying all the necessary methods, such as "champenoise". Antonio Guerra was a pharmacist and a real visionary, who was able to understand and value the potential of the vine- yards of Bierzo, far before the appellations, the architectural & design wineries, the wine tours and the poetic back labels even existed. Applying revolutionary winemaking techniques and marketing, when the term wasn't probably even invented, Vinos Guerra showed the virtues of the wines from Bierzo to the world. Wines produced with old vineyards of Bierzo, along the Pilgrim Way to Santiago de Compostela, on sunny slopes that conceal Roman and Visigothic treasures. An emotional marketing always combined with the quality of the many products of the winery. -

The Ancient Tale of Anise and Its Long Journey to America

For immediate release Press contact: Daniela Puglielli, Accent PR (908) 212 7846 THE ANCIENT TALE OF ANISE AND ITS LONG JOURNEY TO AMERICA New Orleans, July 2012 -- As part of the “spirited” presentations of the Tales of the Cocktail festival, Distilleria Varnelli cordially invites you to the event “Anise: The Mediterranean Treasure” on Saturday July 28, from 3:00 pm to 4:30 pm at the Queen Anne Ballroom, Hotel Monteleone in New Orleans, LA. The seminar offers a rare occasion to compare different Mediterranean anises, neat and in preparation: Varnelli, as the best Italian dry anise, ouzo, arak, raki, anisado, and anisette. Mixologist Francesco Lafranconi - winner of the TOC 2009 Best Presenter Award- and Orietta Maria Varnelli, CEO of Distilleria Varnelli S.p.a., will transport attendees through an incredible historical and cultural journey, including an exclusive tasting of anise-based Varnelli’s liqueurs and aperitifs. Renowned mixologists from London, Anistatia Miller and Jared Brown, will bring their experience to the event as well. The program will include also a short yet suggestive cultural presentation about the FIRST American Chapter of the Ordre International des Anysetiers, with Members in Medieval attire that will revive the legend and traditions of the ancient guild of Anysetiers, founded in 1263 in France. Members of the Louisiana Bailliage include Francesco Lanfranconi, who will lead the Chapter as Bailli, Tales of the Cocktail’s founders Ann and Paul Tuennerman, Liz Williams (Chair of Southern Food and Beverage Museum in NOLA), Laura and Chris McMillan of the Museum of American Cocktails – MOTAC, journalists Camper English and Brenda Maitland, mixologist Jacques Bezuidenhout and importer Paolo Domeneghetti. -

Wine Spirits

WINE SPIRITS “il vino fa buon san gue ” literal: good wine makes good blood English equiv: an apple a day keeps the doctor away Vini Frizzanti e Spumanti Ferrari Trento DOC Brut NV 55 VAL D’ AOSTA Chardonnay Grosjean Vigne Rovettaz ‘16 62 Franciacorta 1701 Brut NV (Biodynamic, Organic) 60 Petite Arvine Chardonnay, Pinot Nero, Lombardia Chateau Feuillet Traminer ‘17 60 Gianluca Viberti Casina Bric 460 Gewurztraminer Sparkling Rose Brut 52 Nebbiolo, Piemonte PIEMONTE Contratto Millesimato Extra Brut ‘12 68 La Scolca Gavi Black Label ‘15 92 Pinot Nero, Chardonnay (Bottle Fermented, Cortese Natural Fermentation), Piedmont Vigneti Massa “Petit Derthona” ‘17 48 La Staffa “Mai Sentito!” (Frizzante) ’17 39 Timorasso Verdicchio (Certified Organic, Pet’Nat, Bottle Fermented) Marche VENETO Palinieri “Sant’Agata” Lambrusco Sorbara ’18 32 Suavia “Massifitti” ‘16 55 Lambrusco Sorbara Trebbiano di Soave Quaresimo Lambrusco (Frizzante) NV 36 Pieropan Soave Classico “Calvarino” ‘16 58 Lambrusco (Biodynamically farmed in Garganega Emilia Romagna!) EMILIA ROMAGNA Ancarani “Perlagioia” ‘16 42 Vini Spumanti Dolci (Sweet) Albana Ancarani “Famoso” ‘16 42 Spinetta Moscato d’Asti (.375) 2017 23 Famoso di Cesena Moscato Ca Dei Quattro Archi “Mezzelune” (Orange) 50 Marenco Brachetto d’Acqui (.375) 2017 23 Albana Brachetto MARCHE Vini Bianchi San Lorenzo “di Gino” Superiore ‘17 42 Verdicchio dei Castelli di Jesi ALTO ALDIGE CAMPANIA Abazzia Novacella ‘17 42 Benito Ferarra Terra d’Uva ‘17 45 Gruner Veltliner Ribolla Gialla Abazzia Novacella ‘17 42 Ciro Picariello BruEmm ‘17 45 Kerner Falanghina Terlano Terlaner ‘17 60 San Giovanni “Tresinus” ‘15 45 Pinot Bianco, Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay Fiano Terlano Vorberg Riserva ‘17 90 Pinot Bianco SICILIA Terlano Rarity 2005 250 Planeta “Eruzione” ‘16 68 Pinot Bianco Carricante, Riesling Tieffenbrunner “Feldmarschall” ‘15 75 CORSICA Müller Thurgau Dom. -

Fall Catalog 2005

4935 McConnell Ave #21, Los Angeles, CA 90066 (310) 306-2822 Fax (310) 821-4555 FallFall CatCatalogalog 20052005 www.BeverageWarehouse.com Beverage Purveyors Since 1970 OPEN TO THE PUBLIC MON-SAT 9am-6pm & SUN 10am-4pm Delivery & Shipping Available Call us today for more details! Brandy Gran Duque D Alba A modern expression of the heroic strength and courage shown by the Gran Duque de Alba, Don Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, Grand Duke of the Regiment of Flanders. The brand Gran Duque de Alba was acquired in 1993. The pale bottle of Gran Duque de Alba Solera Gran Reserva has an unusual, voluptuous shape. On the center of the label, circled in gold, is a portrait of the famous Duke. Mahogany color with gold highlights. Complex bouquet of oak, prune and sherry. Velvety texture with flavors of caramel, chocolate and orange, with a long finish. Calvados -Apple Brandy 10430 Busnel RS VSOP . .$34.95 10637 Captian Apple Jack . .$15.95 12170 Coeur De Lion VSOP Pays d Auge . .$63.95 12997 Noble Dame . .$21.95 Asbach Uralt Brandy Amber. Spicy, dried fruit and raisin aromas. A soft entry leads to a dryish medium-bodied palate with wood spice and mild dried fruit notes. Finishes with a fruity, peppery fade of lean wood notes and peppery alcohol. Pleasant wood and spice notes, but not a lot of complexity. Osocalis Rare Alambic Osocalis first public release is our Rare Alambic Brandy; a blend of Colombard, Pinot Noir, and other Coastal Callifornia grape varieties. Osocalis is a small, artisanal distillery in Soquel, California. -

May 2021 Wine Club

Mediterranean Vineyards may 2021 wine club Dear Friends of Mediterranean Vineyards, As life slowly moves back towards “normal” we are so happy to welcome you back to Mediterranean Vineyards and I look forward to seeing you at an upcoming event. Spring got o to a quick start for us, with bud break in our Nebbiolo block at the estate on April 2nd. at was followed quickly by our Pinot Grigio and Corvina vines the following week as the pleasant spring weather continued. e timeline towards harvest has ocially started and we just hope for no frost and an evenly warm summer to deliver high quality grapes. Now is a great time of year to visit us and see all the new life in the vineyard. While the new vintage has started in the vineyard, I’ve been busy in the cellar bottling wines to make room for the new vintage. We have several new varietals lined up to share with you from the 2020 vintage - Picpoul, Vermentino, plus the return of Albariño! is release contains our rst vintage of Mediterranean Vineyards Chardonnay. We have been receiving many requests in the tasting room for Chardonnay and are excited to share this one with you! is release also contains our second vintages of Estate Cabernet Sauvignon and Nebbiolo. Both of these wines will age elegantly for at least 10 years. We’ll be saving some in our cellar and suggest you age a few bottles of each as well. We know some of you prefer wines young while others prefer wines with more age, and these wines are crafted to deliver now and later. -

Gin Co., Ltd., Used to Supply a Very Useful " Gigger" a Few Years Ago

·---=:::::, BARFLIES AND .... COCKTA_ILS . i Over 300 :Cocktail Recaj_pts- . ·.·~ by HARRY and WYNN with slight contributions From Arthur MOSS ... ~------• . .· . PARIS . ' LECRAM. PRESS. 41, Rue.des Trois-Bornes Copyright by Harry McElhone 19:z 7 ~ t "'· ( J - Dedicated lo I 0. 0. Mc INTYRE President of the I. B. F. PREFACE .. The purpose of this licrle pocket manual is to provide an unerring and infallible guide to that vast army of workers which is engaged in catering to che public from behind bars of the countless " h otels," " buffets, " and "Clubs" of every description rhroughout the English-speal<ing world and on the Continent. In this new edition there is . much of added interest, due to the collaboration of the well know n_ caricaturist Wynn, and the " Around the T own" columnist of the New York Herald, Paris, Arthur Moss. There have bee n a number of handbooks published con taining instructions for the mixing of drinks, etc. , bu( such works are not adaptable by reason of their cumbersome pro porfr:>ns. They are left lying around on shelves arid in odd places, rarely are they readily accessible, and ofren they can not be found at all when wanted. This pocket Cocktail guide, w hich the author most unqualifiedly recommends as the best and only one which has ever been written to fill every requirement, contains about 300 recipes for all kinds of modern cocktails and mixed drinks, together with appro priate coasts and valuable hints and instructions relating to the bar business in all its details, and which, if faithfully studied. -

The Liquor Industry 345

THE LIQUOR INDUSTRY 345 TABLE 38. WINE EXPORTS AS SHOWN BY THE REPORTS OF THE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE, FISCAL YEARS 1901 TO 1925, INCLUSIVE 346 STATISTICS OF THE LIQUOR INDUSTRY TABLE 39, WINE IMPORTS AS SHOWN BY THE REPORTS OF THE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE, FISCAL YEARS 1901 TO 1931, INCLUSIVE THE LIQUOR INDUSTRY 347 TABLE 40. APPARENT CONSUMPTION OF WINE IN THE UNITED STATES, FISCAL YEARS 1912 TO 1932, INCLUSIVE TABLE 41. INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN WINES 1930 (In thousands of gallons) * Estimated. f Less than 1,000 gallons. Source: International Yearbook of Agricultural Statistics. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHIES * YEASTS AND FERMENTATION AHRENS. Das Gahrungs-Problem. In Sammlung Chemischer & Technischer Vortraege. Vol. II. Stuttgart, 1902. ALLEN, PAUL W. Industrial Fermentation. New York, 1926. BITTING, K. G. Yeasts and Their Properties. (Purdue Uni- versity Monograph Series, No. 5.) BUCHNER, E. H., and M. HAHN. Die Zymase Gahrung. Miinchen, 1903. EFFRONT. Biochemical Catalysts. New York, 1917. GREEN-WINDISCH. Die Enzyme. Berlin, 1901. GUILLIERMOND, A. The Yeasts. New York, 1920. HANSEN, E. CHR. Practical Studies in Fermentation. London, 1896. HARDEN, ARTHUR. Alcoholic Fermentation. London, 1923. HENRICI, A. T. Molds, Yeasts, and Actinomycetes. New York, 1930. JORGENSEN. Micro-Organisms of Fermentation. London, 1900. KLOECHER. Fermentation Organisms. London, New York, 1903. LAFAR. Technical Mycology. London, 1910. MAERCKER. Handbuch der Spiritusfabrikation. Berlin, 1908. MATTHEWS, CHAS. G. Manual of Alcoholic Fermentation. London, 1901. OPPENHEIMER. Dis Fermente. Leipzig, 1913-29. RIDEAL, SAMUEL. The Carbohydrates and Alcohol. London, 1920. *The student will find directions to further bibliographies on all of the topics included here, except whiskey, in: West and Berolzheimer. -

Anisette Has Been Used to Disguise the Taste of Medicine

Anisette Has Been Used To Disguise The Taste Of Medicine On July 2nd we observe National Anisette Day. Anisette is an anise-flavored liqueur that is made by distilling aniseed and sometimes adding a sugar syrup. Anisette is popular in Spain, Italy, Portugal and France. Click Here For Other Stories And Videos On South Florida Reporter Pure Anisette should not be drunk straight as its alcoholic content is high enough to cause irritation to the throat. However, mixing it in with coffee, gin, bourbon or water will bring out a bit of a sweet flavor. To enjoy this sweetness without drinking, you can make Anisette cookies! If you are one to grab all of the black jelly beans at Easter, you will surely enjoy this day and the drink that makes it unique, Anisette. Although Anisette does not contain licorice, it does have that sort of distinct flavor. Like absinthe, anisette is created by distilling aniseed, the seed of the anise plant, it is a cousin to both the more well-known absinthe and pastis, but stands apart by including licorice root extract. One popular brand of anisette is Sambuca and stands apart from its fellow anisettes by requiring a sugar content of at least 350g/l. It holds in common with other flavored liquors that it is not typically drunk straight, but instead is commonly mixed in with other liquids for consumption. One common mix for this alcohol is known as a palomita, and is simply anisette mixed into pure cold water. This herb is native to Egypt and is mentioned in ancient Egyptian records. -

Guide to Absinthe

The Guide to Absinthe Written by Laura Bellucci First Edition New Orleans, 2019 Printing by JS Makkos Design by Julia Sevin Special Thanks Ray Bordelon, Historian Ted Breaux Jessica Leigh Graves JS Makkos Alan Moss and all the other green-eyed misfits with a passion for our project Contents History of The Old Absinthe House . 5 Absinthe . 19 Absinthe and The Belle Époque . 29 Holy Herbs . 31 1 2 Le Poison Charles Baudelaire Le vin sait revêtir le plus sordide bouge Wine decks the most sordid shack D'un luxe miraculeux, In gaudy luxury, Et fait surgir plus d'un portique fabuleux Conjures more than one fabulous portal Dans l'or de sa vapeur rouge, In the gold of its red vapour, Comme un soleil couchant dans un ciel Like a sun setting in a nebulous sky . nébuleux. That which has no limits, with opium is L'opium agrandit ce qui n'a pas de yet more vast, bornes, It reels out the infinite longer still, Allonge l'illimité, Sinks depths of time and sensual delight . Approfondit le temps, creuse la volupté, Opium pours in doleful pleasures Et de plaisirs noirs et mornes That fill the soul beyond its capacity . Remplit l'âme au delà de sa capacité. So much for all that, it is not worth the Tout cela ne vaut pas le poison qui poison découle Contained in your eyes, your green eyes, De tes yeux, de tes yeux verts, They are lakes where my soul shivers and Lacs où mon âme tremble et se voit à sees itself overturned . -

Trade Mark Decision O/534/20

O/534/20 TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATION NOS. UK00003379484 AND UK000003379488 BY SPIRIT STILL LTD TO REGISTER THE FOLLOWING TRADE MARKS: SPIRIT STILL AND (SERIES OF 2) AS TRADE MARKS IN CLASSES 33, 35 AND 41 AND IN THE MATTER OF CONSOLIDATED OPPOSITIONS THERETO UNDER NOS. 417026 AND 417031 BY TURL STREET VENTURES LTD BACKGROUND AND PLEADINGS 1. On 28 February 2019, Spirit Still Ltd (“the applicant”) applied to register the following trade marks in the UK: SPIRIT STILL (“the first application”); and (series of 2) (“the second application”) 2. The first and second applications (collectively “the applications”) were published for opposition purposes on 19 April 2019. The applications share identical specifications. The applicant seeks registration for the goods and services shown in the Annex to this decision. 3. The applications were partially opposed on 18 July 2019 by Turl Street Ventures Ltd (“the opponent”). The opposition against the first application is based on sections 5(1) and 5(2)(a) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 (“the Act”). The opposition against the second application is based on section 5(2)(b) of the Act. For both oppositions, the opponent relies on the following mark: Spirit Still UK registration no. 3281752 Filing date 10 January 2018; registration date 7 February 2020 Relying on all goods and services namely: 2 Class 33: Alcoholic beverages (except beers); spirits; whisky, whiskey; scotch whisky; whisky liqueurs; alcoholic wines; liqueurs; alcopops; alcoholic cocktails; excluding the sale of spirit essences and flavourings, yeast, ingredients for brewing of beers and ingredients for the making of wines, spirits and liqueurs. -

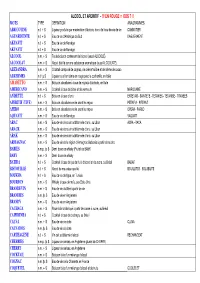

Mots Abricotine Aguardiente Akuavit Akvavit Alcool

ALCOOL ET APERITIF - !!! EN ROUGE = ODS 7 !!! MOTS TYPE DEFINITION ANAGRAMMES ABRICOTINE n.f. + S Liqueur produite par macération d'abricots dans de l'eau-de-vie de vin CABINOTIER AGUARDIENTE n.f. + S Eau de vie d'Amérique du Sud DAGUERAIENT AKUAVIT n.f. + S Eau de vie de Norvège AKVAVIT n.f. + S Eau de vie de Norvège ALCOOL n.m. + S Toute boisson contenant de l'alcool (aussi ALCOOLÉ) ALCOOLAT n.m. + S Alcool distillé sur une substance aromatique (aussi ALCOOLATE) ALEXANDRA n.m. + S Cocktail composé de cognac, de crème fraîche et de crème de cacao ALKERMES n.f. tjs S Liqueur que l'on teinte en rouge avec la cochenille, en Italie AMARETTO n.m. + S Boisson alcoolisée à base de noyaux d'abricots, en Italie AMERICANO n.m. + S Cocktail à base de bitter et de vermouth MAROCAINE ANISETTE n.f. + S Boisson à base d'anis ENTETAIS - SAINTETE - TETANIES - TETANISE - TITANEES APERITIF (TIVE) n.m. + S Boisson alcoolisée servie avant les repas PETRIFIA - PIFERAIT APERO n.m. + S Boisson alcoolisée servie avant les repas OPERA - PAREO AQUAVIT n.m. + S Eau de vie de Norvège VAQUAIT ARAC n.m. + S Eau-de-vie de raisin additionnée d'anis, au Liban ACRA - RACA ARACK n.m. + S Eau-de-vie de raisin additionnée d'anis, au Liban ARAK n.m. + S Eau-de-vie de raisin additionnée d'anis, au Liban ARMAGNAC n.m. + S Eau-de-vie de la région d'Armagnac élaborée à partir de raisins BABIES n.m.p. tjs S Demi dose de whisky (Pluriel de BABY) BABY n.m.