Saline and Arid Soils: Impact on Bacteria, Plants, and Their Interaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaea, Bacteria and Termite, Nitrogen Fixation and Sustainable Plants Production

Sun W et al . (2021) Notulae Botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca Volume 49, Issue 2, Article number 12172 Notulae Botanicae Horti AcademicPres DOI:10.15835/nbha49212172 Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca Re view Article Archaea, bacteria and termite, nitrogen fixation and sustainable plants production Wenli SUN 1a , Mohamad H. SHAHRAJABIAN 1a , Qi CHENG 1,2 * 1Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Biotechnology Research Institute, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] ; [email protected] 2Hebei Agricultural University, College of Life Sciences, Baoding, Hebei, 071000, China; Global Alliance of HeBAU-CLS&HeQiS for BioAl-Manufacturing, Baoding, Hebei 071000, China; [email protected] (*corresponding author) a,b These authors contributed equally to the work Abstract Certain bacteria and archaea are responsible for biological nitrogen fixation. Metabolic pathways usually are common between archaea and bacteria. Diazotrophs are categorized into two main groups namely: root- nodule bacteria and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Diazotrophs include free living bacteria, such as Azospirillum , Cupriavidus , and some sulfate reducing bacteria, and symbiotic diazotrophs such Rhizobium and Frankia . Three types of nitrogenase are iron and molybdenum (Fe/Mo), iron and vanadium (Fe/V) or iron only (Fe). The Mo-nitrogenase have a higher specific activity which is expressed better when Molybdenum is available. The best hosts for Rhizobium legumiosarum are Pisum , Vicia , Lathyrus and Lens ; Trifolium for Rhizobium trifolii ; Phaseolus vulgaris , Prunus angustifolia for Rhizobium phaseoli ; Medicago, Melilotus and Trigonella for Rhizobium meliloti ; Lupinus and Ornithopus for Lupini, and Glycine max for Rhizobium japonicum . Termites have significant key role in soil ecology, transporting and mixing soil. Termite gut microbes supply the enzymes required to degrade plant polymers, synthesize amino acids, recycle nitrogenous waste and fix atmospheric nitrogen. -

Table S5. the Information of the Bacteria Annotated in the Soil Community at Species Level

Table S5. The information of the bacteria annotated in the soil community at species level No. Phylum Class Order Family Genus Species The number of contigs Abundance(%) 1 Firmicutes Bacilli Bacillales Bacillaceae Bacillus Bacillus cereus 1749 5.145782459 2 Bacteroidetes Cytophagia Cytophagales Hymenobacteraceae Hymenobacter Hymenobacter sedentarius 1538 4.52499338 3 Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadales Gemmatimonadaceae Gemmatirosa Gemmatirosa kalamazoonesis 1020 3.000970902 4 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas indica 797 2.344876284 5 Firmicutes Bacilli Lactobacillales Streptococcaceae Lactococcus Lactococcus piscium 542 1.594633558 6 Actinobacteria Thermoleophilia Solirubrobacterales Conexibacteraceae Conexibacter Conexibacter woesei 471 1.385742446 7 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas taxi 430 1.265115184 8 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas wittichii 388 1.141545794 9 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas sp. FARSPH 298 0.876754244 10 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sorangium cellulosum 260 0.764953367 11 Proteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria Myxococcales Polyangiaceae Sorangium Sphingomonas sp. Cra20 260 0.764953367 12 Proteobacteria Alphaproteobacteria Sphingomonadales Sphingomonadaceae Sphingomonas Sphingomonas panacis 252 0.741416341 -

Understanding the Composition and Role of the Prokaryotic Diversity in the Potato Rhizosphere for Crop Improvement in the Andes

Understanding the composition and role of the prokaryotic diversity in the potato rhizosphere for crop improvement in the Andes Jonas Ghyselinck Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor (Ph.D.) in Sciences, Biotechnology Promotor - Prof. Dr. Paul De Vos Co-promotor - Dr. Kim Heylen Ghyselinck Jonas – Understanding the composition and role of the prokaryotic diversity in the potato rhizosphere for crop improvement in the Andes Copyright ©2013 Ghyselinck Jonas ISBN-number: 978-94-6197-119-7 No part of this thesis protected by its copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without written permission of the author and promotors. Printed by University Press | www.universitypress.be Ph.D. thesis, Faculty of Sciences, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium. This Ph.D. work was financially supported by European Community's Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under grant agreement N° 227522 Publicly defended in Ghent, Belgium, May 28th 2013 EXAMINATION COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Savvas Savvides (chairman) Faculty of Sciences Ghent University, Belgium Prof. Dr. Paul De Vos (promotor) Faculty of Sciences Ghent University, Belgium Dr. Kim Heylen (co-promotor) Faculty of Sciences Ghent University, Belgium Prof. Dr. Anne Willems Faculty of Sciences Ghent University, Belgium Prof. Dr. Peter Dawyndt Faculty of Sciences Ghent University, Belgium Prof. Dr. Stéphane Declerck Faculty of Biological, Agricultural and Environmental Engineering Université catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium Dr. Angela Sessitsch Department of Health and Environment, Bioresources Unit AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH, Tulln, Austria Dr. -

Characterization of Sheath Rot Pathogens from Major Rice-Growing

Promotor: Prof. Dr. Ir. Monica Höfte Laboratory of Phytopathology Department of Crop Protection Faculty of Bioscience Engineering Ghent University Co-Promoter: Dr. Ir. Obedi I. Nyamangyoku Department of Crop Science School of agriculture, Rural Development and Agricultural Economics College of Agriculture, Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine University of Rwanda, RWANDA Dean : Prof. Dr. Ir. Marc Van Meirvenne Rector : Prof. Dr. Anne De Paepe ii Ir. Vincent de Paul Bigirimana Characterization of sheath rot pathogens from major rice- growing areas in Rwanda Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor (PhD) in Applied Biological Sciences iii Dutch translation of the title: Karakterisatie van pathogenen die “sheath rot” veroorzaken in de belangrijkste rijstgebieden in Rwanda Cover illustration: Some sheath rot disease features: - Left upper side: microscopic picture of the reverse side of Fusarium andiyazi isolate RFNG10 on PDA medium; - Left lower side: microscopic picture of the front side of Fusarium andiyazi isolate RFNG10 isolate on PDA medium; - Center: illustration of rice sheath rot symptoms on a rice plant; - Right side: illustration of a phylogenetic tree of Pseudomonas isolates associated with rice sheath rot symptoms in Rwanda and the Philippines. This work was financially supported by a PhD grant from the Belgian Technical Cooperation (BTC) (reference number: 10RWA/0018). Additional funding was provided by the Ghent University. Cite as: BIGIRIMANA V.P. 2016. Characterisation of sheath rot pathogens from major rice-growing areas in Rwanda. PhD thesis, Ghent University, Belgium. ISBN Number: 978-90-5989-904-9 The author and the Promoters give the authorization to consult and to copy parts of this work for personal use only. -

Control of Phytopathogenic Microorganisms with Pseudomonas Sp. and Substances and Compositions Derived Therefrom

(19) TZZ Z_Z_T (11) EP 2 820 140 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A01N 63/02 (2006.01) A01N 37/06 (2006.01) 10.01.2018 Bulletin 2018/02 A01N 37/36 (2006.01) A01N 43/08 (2006.01) C12P 1/04 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 13754767.5 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 27.02.2013 PCT/US2013/028112 (87) International publication number: WO 2013/130680 (06.09.2013 Gazette 2013/36) (54) CONTROL OF PHYTOPATHOGENIC MICROORGANISMS WITH PSEUDOMONAS SP. AND SUBSTANCES AND COMPOSITIONS DERIVED THEREFROM BEKÄMPFUNG VON PHYTOPATHOGENEN MIKROORGANISMEN MIT PSEUDOMONAS SP. SOWIE DARAUS HERGESTELLTE SUBSTANZEN UND ZUSAMMENSETZUNGEN RÉGULATION DE MICRO-ORGANISMES PHYTOPATHOGÈNES PAR PSEUDOMONAS SP. ET DES SUBSTANCES ET DES COMPOSITIONS OBTENUES À PARTIR DE CELLE-CI (84) Designated Contracting States: • O. COUILLEROT ET AL: "Pseudomonas AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB fluorescens and closely-related fluorescent GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO pseudomonads as biocontrol agents of PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR soil-borne phytopathogens", LETTERS IN APPLIED MICROBIOLOGY, vol. 48, no. 5, 1 May (30) Priority: 28.02.2012 US 201261604507 P 2009 (2009-05-01), pages 505-512, XP55202836, 30.07.2012 US 201261670624 P ISSN: 0266-8254, DOI: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2009.02566.x (43) Date of publication of application: • GUANPENG GAO ET AL: "Effect of Biocontrol 07.01.2015 Bulletin 2015/02 Agent Pseudomonas fluorescens 2P24 on Soil Fungal Community in Cucumber Rhizosphere (73) Proprietor: Marrone Bio Innovations, Inc. -

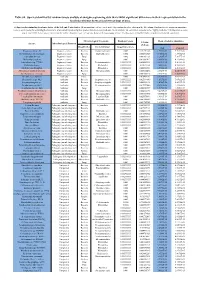

Table S8. Species Identified by Random Forests Analysis of Shotgun Sequencing Data That Exhibit Significant Differences In

Table S8. Species identified by random forests analysis of shotgun sequencing data that exhibit significant differences in their representation in the fecal microbiomes between each two groups of mice. (a) Species discriminating fecal microbiota of the Soil and Control mice. Mean importance of species identified by random forest are shown in the 5th column. Random forests assigns an importance score to each species by estimating the increase in error caused by removing that species from the set of predictors. In our analysis, we considered a species to be “highly predictive” if its importance score was at least 0.001. T-test was performed for the relative abundances of each species between the two groups of mice. P-values were at least 0.05 to be considered statistically significant. Microbiological Taxonomy Random Forests Mean of relative abundance P-Value Species Microbiological Function (T-Test) Classification Bacterial Order Importance Score Soil Control Rhodococcus sp. 2G Engineered strain Bacteria Corynebacteriales 0.002 5.73791E-05 1.9325E-05 9.3737E-06 Herminiimonas arsenitoxidans Engineered strain Bacteria Burkholderiales 0.002 0.005112829 7.1580E-05 1.3995E-05 Aspergillus ibericus Engineered strain Fungi 0.002 0.001061181 9.2368E-05 7.3057E-05 Dichomitus squalens Engineered strain Fungi 0.002 0.018887472 8.0887E-05 4.1254E-05 Acinetobacter sp. TTH0-4 Engineered strain Bacteria Pseudomonadales 0.001333333 0.025523638 2.2311E-05 8.2612E-06 Rhizobium tropici Engineered strain Bacteria Rhizobiales 0.001333333 0.02079554 7.0081E-05 4.2000E-05 Methylocystis bryophila Engineered strain Bacteria Rhizobiales 0.001333333 0.006513543 3.5401E-05 2.2044E-05 Alteromonas naphthalenivorans Engineered strain Bacteria Alteromonadales 0.001 0.000660472 2.0747E-05 4.6463E-05 Saccharomyces cerevisiae Engineered strain Fungi 0.001 0.002980726 3.9901E-05 7.3043E-05 Bacillus phage Belinda Antibiotic Phage 0.002 0.016409765 6.8789E-07 6.0681E-08 Streptomyces sp. -

Redalyc.Análisis De Pseudomonas Fitopatógenas Usando Métodos

Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología ISSN: 0185-3309 [email protected] Sociedad Mexicana de Fitopatología, A.C. México Slabbinck, Bram; De Baets, Bernard; Dawyndt, Peter; Vos, Paul De Análisis de Pseudomonas Fitopatógenas Usando Métodos Inteligentes de Aprendizaje: Un Enfoque General Sobre Taxonomía y Análisis de Ácidos Grasos Dentro del Género Pseudomonas Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología, vol. 28, núm. 1, 2010, pp. 1-16 Sociedad Mexicana de Fitopatología, A.C. Texcoco, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=61214206001 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto REVISTA MEXICANA DE FITOPATOLOGÍA/1 Análisis de Pseudomonas Fitopatógenas Usando Métodos Inteligentes de Aprendizaje: Un Enfoque General Sobre Taxonomía y Análisis de Ácidos Grasos Dentro del Género Pseudomonas Analysis of Plant-Pathogenic Pseudomonas Species Using Intelligent Learning Methods: A General Focus on Taxonomy and Fatty Acid Analysis Within the Genus Pseudomonas Bram Slabbinck, Bernard De Baets, Research Group Knowledge-based Systems, Department of Applied Mathematics, Biometrics and Process Control, Ghent University, Coupure links 653, 9000 Ghent, Belgium, Peter Dawyndt, Department of Applied Mathematics and Computer Science, Ghent University, Krijgslaan 281 S9, 9000 Ghent, Belgium y Paul De Vos, Research Group Knowledge-based Systems, Department of Applied Mathematics, Biometrics and Process Control, Ghent University, Coupure links 653, 9000 Ghent, Belgium. (Recibido: Septiembre 20, 2009 Aceptado Enero 12, 2010) Slabbinck, B., De Baets, B., Dawyndt, P., y De Vos, P. -

Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus Pseudomonas Lead to the Rearrangement of Several Species and the Definition of New Genera

biology Article Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus Pseudomonas Lead to the Rearrangement of Several Species and the Definition of New Genera Zaki Saati-Santamaría 1,2,* , Ezequiel Peral-Aranega 1,2 , Encarna Velázquez 1,2,3, Raúl Rivas 1,2,3 and Paula García-Fraile 1,2,3 1 Microbiology and Genetics Department, University of Salamanca, 37007 Salamanca, Spain; [email protected] (E.P.-A.); [email protected] (E.V.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (P.G.-F.) 2 Institute for Agribiotechnology Research (CIALE), 37185 Salamanca, Spain 3 Associated Research Unit of Plant-Microorganism Interaction, University of Salamanca-IRNASA-CSIC, 37008 Salamanca, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Pseudomonas represents a very important bacterial genus that inhabits many environments and plays either prejudicial or beneficial roles for higher hosts. However, there are many Pseudomonas species which are too divergent to the rest of the genus. This may interfere in the correct development of biological and ecological studies in which Pseudomonas are involved. Thus, we aimed to study the correct taxonomic placement of Pseudomonas species. Based on the study of their genomes and some evolutionary-based methodologies, we suggest the description of three new genera (Denitrificimonas, Parapseudomonas and Neopseudomonas) and many reclassifications of species Citation: Saati-Santamaría, Z.; previously included in Pseudomonas. Peral-Aranega, E.; Velázquez, E.; Rivas, R.; García-Fraile, P. Abstract: Pseudomonas is a large and diverse genus broadly distributed in nature. Its species play Phylogenomic Analyses of the Genus relevant roles in the biology of earth and living beings. Because of its ubiquity, the number of new Pseudomonas Lead to the species is continuously increasing although its taxonomic organization remains quite difficult to Rearrangement of Several Species and unravel. -

Names of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, 1864-2003

Names of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, 1864–2004 J.M. Young, Landcare Research, Private Bag 92170, Auckland, New Zealand: [email protected] (Convener) C.T. Bull, US Department of Agriculture, 1636 E Alisal Street, Salinas, CA 93905, USA: [email protected] S.H. De Boer, Centre for Animal and Plant Health, 93 Mount Edward Road, Charlottetown, PE C1A 5T1, Canada: [email protected] G. Firrao, Dipartimento di Biologia Applicata alla Difesa delle Piante, Universita, via Scienze 208, 33100 Udine, Italy: [email protected] G.E. Saddler, Scottish Agricultural Science Agency, 82 Craigs Road, Edinburgh EH12 8NJ, Scotland: [email protected] D.E. Stead, Central Science Laboratory, Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Sand Hutton, York, YO4 1LN, United Kingdom: [email protected] Y. Takikawa Plant Pathology Laboratory, Shizuoka University, 836 Ohya, Shizuoka 422, Japan: [email protected] This list contains the names of all plant pathogenic bacteria that have been effectively and validly published in terms of the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes (‘the Code’ – hitherto the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria) (Lapage et al. 1992) and the Standards for Naming Pathovars (Dye et al. 1980), and their revision (Young et al. 1991a). Included are species names from the Approved Lists of Bacterial Names (Skerman et al. 1980), pathovar names listed by Dye et al. (1980), and names of pathogens reported since 1980. In recent years, the taxonomy of plant pathogenic bacteria has been extensively revised. For several taxa, especially the Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas syringae van Hall 1902 and Xanthomonas campestris (Pammel 1895) Dowson 1939, these revisions are incomplete. -

Comprehensive List of Names of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, 1980-2007

001_JPP_Letter_551 16-11-2010 14:12 Pagina 551 Journal of Plant Pathology (2010), 92 (3), 551-592 Edizioni ETS Pisa, 2010 551 LETTER TO THE EDITOR COMPREHENSIVE LIST OF NAMES OF PLANT PATHOGENIC BACTERIA, 1980-2007 C.T. Bull1, S.H. De Boer2, T.P. Denny3, G. Firrao4, M. Fischer-Le Saux5, G.S. Saddler6, M. Scortichini7, D.E. Stead8 and Y. Takikawa9 1United States Department of Agriculture, 1636 E. Alisal Street, Salinas, CA 93905, USA 2Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 93 Mount Edward Road, Charlottetown, PE C1A 5T1, Canada 3University of Georgia, Plant Pathology Department, Plant Science Building, Athens, GA 30602-7274, USA 4Dipartimento di Biologia Applicata alla Difesa delle Piante, Università degli Studi, Via Scienze 208, 33100 Udine, Italy 5UMR de Pathologie Végétale, INRA, BP 60057, 49071 Beaucouzé Cedex, France 6Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture, Roddinglaw Road, Edinburgh EH12 9FJ, UK 7CRA. Centro di Ricerca per la Frutticoltura, Via di Fioranello 52, 00134 Roma, Italy 8Food and Environment Research Agency, Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ, UK 9Faculty of Agriculture, Shizuoka University, 836 Ohya, Shizuoka 422-8529, Japan SUMMARY INTRODUCTION The names of all plant pathogenic bacteria which The nomenclature of bacterial plant pathogens, like have been effectively and validly published in terms of that of many other life forms, is constantly changing in the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria and response to new insights and our understanding of rela- the Standards for Naming Pathovars are listed to pro- tionships among bacteria. For example, the taxonomy vide an authoritative register of names for use by au- of the family Enterobacteriaceae has been extensively re- thors, journal editors and others who require access to vised since the publication of the previous comprehen- currently correct nomenclature. -

Low Bacterial Community Diversity in Two Introduced Aphid Pests Revealed with 16S Rrna Amplicon Sequencing

Low bacterial community diversity in two introduced aphid pests revealed with 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing Francisca Zepeda-Paulo1, Sebastían Ortiz-Martínez1, Andrea X. Silva2 and Blas Lavandero1 1 Laboratorio de Control Biológico/Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile 2 AUSTRAL-omics Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Austral de Chile, Valdivia, Chile ABSTRACT Bacterial endosymbionts that produce important phenotypic effects on their hosts are common among plant sap-sucking insects. Aphids have become a model system of insect-symbiont interactions. However, endosymbiont research has focused on a few aphid species, making it necessary to make greater efforts to other aphid species through different regions, in order to have a better understanding of the role of endosymbionts in aphids as a group. Aphid endosymbionts have frequently been studied by PCR-based techniques, using species-specific primers, nevertheless this approach may omit other non-target bacteria cohabiting a particular host species. Advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies are complementing our knowledge of microbial communities by allowing us the study of whole microbiome of different organisms. We used a 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing approach to study the microbiome of aphids in order to describe the bacterial community diversity in introduced populations of the cereal aphids, Sitobion avenae and Rhopalosiphum padi in Chile (South America). An absence of secondary endosymbionts and two common secondary endosymbionts of aphids were found in the aphids R. padi and S. avenae, respectively. Of those endosymbionts, Regiella insecticola was the dominant secondary endosymbiont among the aphid samples. In addition, the presence of a previously unidentified bacterial species closely related to a phytopathogenic Pseudomonad species was detected. -

Comparative Phylogenomic Analysis Reveals Evolutionary Genomic

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.02.446850; this version posted June 5, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Comparative phylogenomic analysis reveals evolutionary genomic 2 changes and novel toxin families in endophytic Liberibacter 3 pathogens 4 5 Yongjun Tan1, Cindy Wang1, Theresa Schneider1, Huan Li1, Robson Francisco de Souza2, 6 Xueming Tang3, Tzung-Fu Hsieh4,5, Xu Wang6,7,8, Xu Li4,5, and Dapeng Zhang1,9,* 7 8 1Department of Biology, College of Arts & Sciences, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63103 9 2Departamento de Microbiologia, Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, Universidade de São Paulo, 10 São Paulo 05508-900, Brazil 11 3School of Agriculture and Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China 12 4Department of Plant and Microbial Biology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 13 5Plants for Human Health Institute, North Carolina State University, Kannapolis, NC 28081 14 6Department of Pathobiology, College of Veterinary Medicine, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 15 36849 16 7Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station, Auburn University, Auburn, AL 36849 17 8HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL 35806 18 9Bioinformatics and Computational Biology Program, College of Arts & Sciences, Saint Louis 19 University, St. Louis, MO 63103 20 21 Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to D.Z. (email: 22 [email protected]) 23 24 Running title: Comparative Phylogenomics of Liberibacter Pathogens 25 Keywords: Liberibacter pathogens, huanglongbing, zebra chip, toxins, prophages, 26 pathogenesis, evolution, comparative genomics 27 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.02.446850; this version posted June 5, 2021.