The 2Nd Infantry Division's Assault on Korea's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoot-Out at Rimling Junction, January 8–9, 1945 by Rufus Dalton, 397-H

Shoot-Out at Rimling Junction, January 8–9, 1945 by Rufus Dalton, 397-H Why another article about the battle of Rimling? That is a good question. I feel one last one is due because the story of the last two days of that battle has not been told. This was when the very life of the 2nd Battalion, 397th Infantry was on the line with a pitched battle going on within the town itself. The stories of the individual men involved have not been fully told. This article is an attempt to use their stories to give a composite feeling of what those last two days were like. The Rimling battle lasted from 0005 hours, January 1, 1945, until shortly after dark on January 9. It might be helpful to outline the main events of those days. I used Operations of the 397th Infantry Regiment 100th Infantry Division (the monthly narrative report submitted by the 397th’s commander) to glean the following: December 31 – 1st Battalion was in position at Bettviller. – 2nd Battalion was in reserve around Guising and Gare de Rohrbach. – 3rd Battalion was on the main line of resistance (MLR), in and around Rimling. January 1 – 3rd Battalion at 0005 was hit by a major enemy attack and held, but the 44th Division, on the 3rd Battalion’s left flank, fell back, exposing the Battalion’s left flank. January 2 – 3rd Battalion held onto its position. – 1st and 2nd platoons of Company G (2nd Bn.) were moved up to the MLR to shore up the left flank of the 3rd Battalion. -

H3200 HEARTBREAK RIDGE (USA, 1986) (Other Titles: Gunny; Le Maitre De Guerre)

H3200 HEARTBREAK RIDGE (USA, 1986) (Other titles: Gunny; Le maitre de guerre) Credits: director, Clint Eastwood ; writer, James Carabatsos. Cast: Clint Eastwood, Martha Mason, Everett McGill, Moses Gunn. Summary: War melodrama set in 1983 in the U.S. and Grenada. There are no more wars to fight, but Gunnery Sergeant Tom Highway (Eastwood) still has a lot of fight left in him. He is on his last tour of duty before retirement, a battle- scarred veteran of Korea (Medal of Honor winner) and Vietnam going nose- to-nose with irreverent recruits and eyeball-to-eyeball with incompetent officers. He is also a closet romantic hoping to rekindle a relationship with his ex-wife (Mason). He is tested one final time as he leads his recon platoon in the 1983 U.S. invasion of Grenada. Adair, Gilbert. Hollywood’s Vietnam [GB] (p. 171) Ansen, David. “The arts: Movies: A new beach for an old leatherneck” Newsweek 108 (Dec 15, 1986), p. 83. [Reprinted in Film review annual 1987] Arnold, Christine. “Eastwood’s foul-mouthed Marine land” Miami herald (Dec 6, 1986), p. 1D. Attanasio, Paul. “Movies: Man o’ war: Eastwood’s troubled ‘Heartbreak ridge’” Washington post (Dec 5, 1986), p. C1. Benson, Sheila. “Movie review: Eastwood reworks misfits formula in routine ‘Ridge’” Los Angeles times (Dec 5, 1986), Calendar, p. 1. [Reprinted in Film review annual 1987] Blowen, Michael. Eastwood gets back to basic mayhem” Boston globe (Dec 5, 1986), Arts and film, p. 42. Canby, Vincent. “Film: Clint Eastwood in ‘Heartbreak ridge’” New York times 136 (Dec 5, 1986), p. -

The Graybeards Presidential Envoy to UN Forces: Kathleen Wyosnick the Magazine for Members and Veterans of the Korean War

Staff Officers The Graybeards Presidential Envoy to UN Forces: Kathleen Wyosnick The Magazine for Members and Veterans of the Korean War. P.O. Box 3716, Saratoga, CA 95070 The Graybeards is the official publication of the Korean War Veterans Association, PH: 408-253-3068 FAX: 408-973-8449 PO Box, 10806, Arlington, VA 22210, (www.kwva.org) and is published six times Judge Advocate: Sherman Pratt per year for members of the Association. 1512 S. 20th St., Arlington, VA 22202 PH: 703-521-7706 EDITOR Vincent A. Krepps 24 Goucher Woods Ct. Towson, MD 21286-5655 Dir. for Washington, DC Affairs: J. Norbert Reiner PH: 410-828-8978 FAX: 410-828-7953 6632 Kirkley Ave., McLean, VA 22101-5510 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH/FAX: 703-893-6313 MEMBERSHIP Nancy Monson National Chaplain: Irvin L. Sharp, PO Box 10806, Arlington, VA 22210 16317 Ramond, Maple Hights, OH 44137 PH: 703-522-9629 PH: 216-475-3121 PUBLISHER Finisterre Publishing Incorporated National Asst. Chaplain: Howard L. Camp PO Box 12086, Gainesville, FL 32604 430 S. Stadium Dr., Xenia, OH 45385 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH: 937-372-6403 National KWVA Headquarters Korean Ex-POW Associatiion: Elliot Sortillo, President PRESIDENT Harley J. Coon 2533 Diane Street, Portage, IN 56368-2609 4120 Industrial Lane, Beavercreek, OH 45430 National VA/VS Representative: Norman S. Kantor PH: 937-426-5105 or FAX: 937-426-8415 2298 Palmer Avenue, New Rochelle, NY 10801-2904 E-MAIL: [email protected] PH: 914-632-5827 FAX: 914-633-7963 Office Hours: 9am to 5 pm (EST) Mon.–Fri. -

The Squad Leader Makes the Difference

The Squad Leader Makes the Difference Readings on Combat at the Squad Level Volume I Lieutenant M.M. Obalde and Lieutenant A.M. Otero United States Marine Corps Marine Corps Warfighting Lab Marine Corps Combat Development Command Quantico, Virginia 22134 August 1998 1 United States Marine Corps Marine Corps Warfighting Lab Marine Corps Combat Development Command Quantico, Virginia 22134 May 1998 FOREWORD In combat, the actions of individual leaders affect the outcome of the entire battle. Squad leaders make decisions and take actions which can affect the operational and strategic levels of war. Well-trained squad leaders play an important role as combat decisionmakers on the battlefield. Leaders who show initiative, judgment, and courage will achieve decisive results not only at the squad level, but in the broader context of the battle. Without competent squad leaders, capable of carrying out a commander’s intent, even the best plans are doomed to failure. This publication illustrates how bold, imaginative squad leaders impact the outcome of a battle or campaign. The historical examples here represent some of the cases in which squad leaders were able to change the course of history. In each case, the squad leader had to make a quick decision without direct orders, act independently, and accept responsibility for the results. Short lessons are presented at the end of each story. These lessons should help you realize how important your decisions are to your Marines and your commander. In combat, you must think beyond the squad level. You must develop opportunities for your commander to exploit. Your every action must support your commander’s intent. -

The Attack Will Go on the 317Th Infantry Regiment in World War Ii

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2003 The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II Dean James Dominique Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Dominique, Dean James, "The tta ack will go on the 317th Infantry Regiment in World War II" (2003). LSU Master's Theses. 3946. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/3946 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ATTACK WILL GO ON THE 317TH INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts In The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Dean James Dominique B.S., Regis University, 1997 August 2003 i ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF MAPS........................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT................................................................................................................. iv INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................1 -

Clint Eastwood

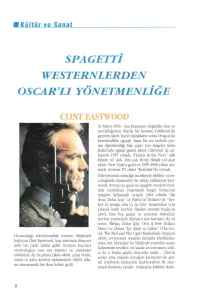

Kültür ue Sanat SPAGETT› WESTERNLERDEN OSCAR'LI YÖNETMENL›–E CLINT EASTWOOD 31 Mayıs 1930 / San Francisco doumlu olan ve çocukluunun büyük bir kısmını California'da geçiren aktör, liseyi bitirdikten sonra Oragon'da kerestecilikle ura˛tı, hatta bir ara orduda yüz- me öretmenlii bile yaptı. Los Angeles fiehir Kolejinde eitim gören aktör, Universal ile an- la˛arak 1955 yılında "Francis in the Navy" adlı filmde rol aldı. Pek çok B-tipi filmde rol alan aktör, New York'a geçti ve 1959-1966 yılları ara- sında western TV dizisi "Rawhide"da oynadı. Televizyonda edindii tecrübeyle birlikte oyun- culuunda minimalist bir üslup yakalayan East- wood, Avrupa'ya geçti ve spagetti western türü- nün unutulmaz yönetmeni Sergio Leone'nin spagetti üçlüsünde oynadı. 1964 yılında "Bir Avuç Dolar ›çin" (A Fistful of Dollars) ile "her- kes ya zengin olur ya da ölür" temasından yola çıkarak kanlı kovboy filmleri serisine ba˛layan aktör, ba˛ı bo˛ gezen ve acımasız Amerikalı kovboy portresiyle dünyaca üne kavu˛tu. ›ki yıl sonra "Birkaç Dolar ›çin" (For A Few Dollars More) ve efsane "›yi, Kötü ve Çirkin" (The Go- od, The Bad and The Ugly) filmlerinde oynayan Oyunculua televizyondaki western filmleriyle aktör, revizyonist western türünün klasiklerine ba˛layan Clint Eastwood, kısa zamanda dünyaca imza attı. Seyirciler bu filmlerde yaratılan sessiz ünlü bir yıldız haline geldi. Kariyeri boyunca kahramanı sevdiler, ne kadar az konu˛ursa etki- oyunculuun yanı sıra yapımcı ve yönetmen si de o kadar güçlü oluyordu sanki... Clint'in yönleriyle de ön plana çıkan aktör, uzun boylu, sessiz ama anlamlı duru˛ları Leone'nin de gör- sessiz ve kaba kovboy tiplemesiyle 1960'lı yılla- sel üslubuyla birle˛erek Eastwood'un ilk sine- rın sinemasında bir ikon haline geldi. -

Cmh Koreanwar Medal of Honor.Pdf

Medal of Honor Recipients Korean War *ABRELL, CHARLES G. Rank and organization: Corporal, U.S. Marine Corps, Company E, 2d Battalion, 1st Marines, 1st Marine Division (Rein.). Place and date: Hangnyong, Korea, 10 June 1951. Entered service at: Terre Haute, Ind. Born: 12 August 1931, Terre Haute, Ind. Citation: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty while serving as a fire team leader in Company E, in action against enemy aggressor forces. While advancing with his platoon in an attack against well- concealed and heavily fortified enemy hill positions, Cpl. Abrell voluntarily rushed forward through the assaulting squad which was pinned down by a hail of intense and accurate automatic-weapons fire from a hostile bunker situated on commanding ground. Although previously wounded by enemy hand grenade fragments, he proceeded to carry out a bold, single-handed attack against the bunker, exhorting his comrades to follow him. Sustaining 2 additional wounds as he stormed toward the emplacement, he resolutely pulled the pin from a grenade clutched in his hand and hurled himself bodily into the bunker with the live missile still in his grasp. Fatally wounded in the resulting explosion which killed the entire enemy guncrew within the stronghold, Cpl. Abrell, by his valiant spirit of self- sacrifice in the face of certain death, served to inspire all his comrades and contributed directly to the success of his platoon in attaining its objective. His superb courage and heroic initiative sustain and enhance the highest traditions of the U.S. -

The Korean War

N ATIO N AL A RCHIVES R ECORDS R ELATI N G TO The Korean War R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 1 0 3 COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 N AT I ONAL A R CH I VES R ECO R DS R ELAT I NG TO The Korean War COMPILED BY REBEccA L. COLLIER R EFE R ENCE I NFO R MAT I ON P A P E R 103 N ATIO N AL A rc HIVES A N D R E C O R DS A DMI N IST R ATIO N W ASHI N GTO N , D C 2 0 0 3 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives records relating to the Korean War / compiled by Rebecca L. Collier.—Washington, DC : National Archives and Records Administration, 2003. p. ; 23 cm.—(Reference information paper ; 103) 1. United States. National Archives and Records Administration.—Catalogs. 2. Korean War, 1950-1953 — United States —Archival resources. I. Collier, Rebecca L. II. Title. COVER: ’‘Men of the 19th Infantry Regiment work their way over the snowy mountains about 10 miles north of Seoul, Korea, attempting to locate the enemy lines and positions, 01/03/1951.” (111-SC-355544) REFERENCE INFORMATION PAPER 103: NATIONAL ARCHIVES RECORDS RELATING TO THE KOREAN WAR Contents Preface ......................................................................................xi Part I INTRODUCTION SCOPE OF THE PAPER ........................................................................................................................1 OVERVIEW OF THE ISSUES .................................................................................................................1 -

Handbook on USSR Military Forces, Chapter VI: Fortifications War Department (USA)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln DOD Military Intelligence U.S. Department of Defense 1-1946 Handbook on USSR Military Forces, Chapter VI: Fortifications War Department (USA) Robert L. Bolin , Depositor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dodmilintel War Department (USA) and Bolin, Robert L. , Depositor, "Handbook on USSR Military Forces, Chapter VI: Fortifications" (1946). DOD Military Intelligence. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dodmilintel/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in DOD Military Intelligence by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Technical Manual, TM 30-430 Handbook on USSR Military Forces Chapter VI Fortifications Robert L. Bolin, Depositor University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Technical Manual, TM 30-430, Chapter VI 1 January 1946 Handbook on USSR Military Forces Chapter VI Fortifications War Department Washington, DC Comments The copy digitized was borrowed from the Marshall Center Research Library, APO, AE 09053-4502. Abstract TM 30-340, Handbook on USSR Military Forces, was “published in installments to expedite dissemination to the field.” TM30-430, Chapter VI, 1 January 1946, “Fortifications,” is a detailed discussion of earthworks and structures used for defensive purposes. This chapter is illustrated with numerous drawings, diagrams, and charts. This manual is listed in WorldCat under Accession Number: OCLC: 19989681 1 Jan 46 TM 30-430 CHAPTER VI FORTIFICATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Figure Section I. -

2Nd Infantry Division

2nd Infantry Division Korean War Awards General Orders 1951 823 Thru 829 Korean War Project Record: 2ID Generals Orders File - GO-170 PID: 11 National Archives and Records Administration College Park, Maryland Records: United States Army Unit Name: Second Infantry Division Record Group: RG407 Editor: Hal Barker Korean War Project P.O. Box 180190 Dallas, TX 75218-0190 http://www.koreanwar.org Search 2nd Division Awards Database --· DECL\SSIFIED-------- --- I :\ut:wri:y .AUJ1L~F j Gy !L :-.·-\R.S. Date _'-l[ 'J..-~ I -----==~~~--...--...~ HEAOOUART ERS 2d Infantry Division APO 248 c/o Postmaster · San Fra ncisco California GENERAL ORDERS 6 December 1951 nm.mr:R 823 Section I A111ARD OF THE SILVER S'l'AR--By direction of the Preddent, under the provisions of the Act 'of .Congress, approved 9 July 1918 (WD Bul 43, 1918), and pursuant 'to authority in AR 600-45, the 'silver Star for gallantry in action ~s a·warded to the following name d enlisted men: CORPORAL RA:10N DeLEON, RA25857478, (then Private First Class), :Infan try, Up it~d States Army, a member of Company I,. 38th Infantry Regiment, 2d Infantry Division 1 , distinguished himself by gallantry in action on 30 July 1951 in the vicinity of Taeusan, Korea. ' On this date during Company I' s assault upon enel!!-y positions,, Corporal DeLeon was serving ·in the capacity of a wireman for th~ 1nortar sect ion. DQspite the intense srha:ll arms and automatic weapons f-ire · he laid communicationwire from the supporting mor t a r section to the ·forv1ard observer's position. -

Big Bear Back Country Off-Highway Vehicle

Travel Analysis Report United States Department of Big Bear Back Country Place Agriculture Off-Highway Vehicle Use Forest Service November 2015 Mountaintop Ranger District, San Bernardino National Forest San Bernardino County, California For More Information Contact: Tasha Hernandez, Environmental Coordinator San Bernardino National Forest [email protected] 909-382-2905 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. -

XXIV:9) Clint Eastwood, the OUTLAW JOSEY WALES (1976, 135 Min.)

Please turn off cellphones during screening March 20, 2012 (XXIV:9) Clint Eastwood, THE OUTLAW JOSEY WALES (1976, 135 min.) Directed by Clint Eastwood Screenplay by Philip Kaufman and Sonia Chernus Based on the novel by Forrest Carter Produced by Robert Daley Original Music by Jerry Fielding Cinematography by Bruce Surtees Film Editing by Ferris Webster Clint Eastwood…Josey Wales Chief Dan George…Lone Watie Sondra Locke…Lee Bill McKinney…Terrill John Vernon…Fletcher Paula Trueman…Grandma Sarah Sam Bottoms...Jamie Geraldine Keams…Little Moonlight Woodrow Parfrey…Carpetbagger John Verros…Chato Will Sampson…Ten Bears John Quade…Comanchero Leader John Russell…Bloody Bill Anderson Charles Tyner…Zukie Limmer John Mitchum…Al Kyle Eastwood…Josey's Son Richard Farnsworth…Comanchero 1996 National Film Registry 1983 Sudden Impact, 1982 Honkytonk Man, 1982 Firefox, 1980 Bronco Billy, 1977 The Gauntlet, 1976 The Outlaw Josey Wales, 1975 The Eiger Sanction, 1973 Breezy, 1973 High Plains Drifter, Clint Eastwood (b. Clinton Eastwood Jr., May 31, 1930, San 1971 Play Misty for Me, and 1971 The Beguiled: The Storyteller. Francisco, California) has won five Academy Awards: best He has 67 acting credits, some of which are 2008 Gran Torino, director and best picture for Million Dollar Baby (2004), the 2004 Million Dollar Baby, 2000 Space Cowboys, 1999 True Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award (1995) and best director and Crime, 1997 Absolute Power, 1995 The Bridges of Madison best picture for Unforgiven (1992). He has directed 35 films, County, 1993 A Perfect