Palestinian Armed Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Terrorist Organizations

Order Code RL32223 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Foreign Terrorist Organizations February 6, 2004 Audrey Kurth Cronin Specialist in Terrorism Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Huda Aden, Adam Frost, and Benjamin Jones Research Associates Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations Summary This report analyzes the status of many of the major foreign terrorist organizations that are a threat to the United States, placing special emphasis on issues of potential concern to Congress. The terrorist organizations included are those designated and listed by the Secretary of State as “Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” (For analysis of the operation and effectiveness of this list overall, see also The ‘FTO List’ and Congress: Sanctioning Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations, CRS Report RL32120.) The designated terrorist groups described in this report are: Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade Armed Islamic Group (GIA) ‘Asbat al-Ansar Aum Supreme Truth (Aum) Aum Shinrikyo, Aleph Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) Communist Party of Philippines/New People’s Army (CPP/NPA) Al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group, IG) HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) Hizballah (Party of God) Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) Jemaah Islamiya (JI) Al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) Kahane Chai (Kach) Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK, KADEK) Lashkar-e-Tayyiba -

Palestinian Forces

Center for Strategic and International Studies Arleigh A. Burke Chair in Strategy 1800 K Street, N.W. • Suite 400 • Washington, DC 20006 Phone: 1 (202) 775 -3270 • Fax : 1 (202) 457 -8746 Email: [email protected] Palestinian Forces Palestinian Authority and Militant Forces Anthony H. Cordesman Center for Strategic and International Studies [email protected] Rough Working Draft: Revised February 9, 2006 Copyright, Anthony H. Cordesman, all rights reserved. May not be reproduced, referenced, quote d, or excerpted without the written permission of the author. Cordesman: Palestinian Forces 2/9/06 Page 2 ROUGH WORKING DRAFT: REVISED FEBRUARY 9, 2006 ................................ ................................ ............ 1 THE MILITARY FORCES OF PALESTINE ................................ ................................ ................................ .......... 2 THE OSLO ACCORDS AND THE NEW ISRAELI -PALESTINIAN WAR ................................ ................................ .............. 3 THE DEATH OF ARAFAT AND THE VICTORY OF HAMAS : REDEFINING PALESTINIAN POLITICS AND THE ARAB - ISRAELI MILITARY BALANCE ................................ ................................ ................................ ................................ .... 4 THE CHANGING STRUCTURE OF PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY FORC ES ................................ ................................ .......... 5 Palestinian Authority Forces During the Peace Process ................................ ................................ ..................... 6 The -

1987-1993 — the Intifada: the Palestinian Resistance Mo(Ve)Ment ————————— 7

————————— 1987-1993 — The Intifada: The Palestinian Resistance Mo(ve)ment ————————— 7. 1987-1993 — The Intifada: The Palestinian Resistance Mo(ve)ment1 I. Introduction The Israeli polity saw two major structural changes during the post- colonial era: the creation of the State of Israel in 1948 and the insti- tutionalization of the dual democratic/ military regime after 1967. Despite these two tremendous transformations in terms of popula- tion, economy, territory and bureaucracies, the colonial Zionist Labor Movement (ZLM) proved strong enough to maintain its institutional structure and power. The only long-term political development occurred gradually, with the transition from a monopoly of a single ruling party to a bipartisan “left/right cartel” (see Chapter 5) made up of two Zion- ist party blocks. Although these two blocks competed for power, tribal channeling of polarized hostile feelings closed political space to new actors, while in fact both implemented similar economic policies and supported the dual regime (Ben Porath, 1982; Grinberg, 1991, 2010). The ruling Labor Alignment, in cooperation with the Histadrut and the security establishment, institutionalized the dual regime designed to maintain control of the economy and population on both sides of the Green Line separating sovereign Israel from the Occupied Territories. The Labor Movement ideology, however, was unequipped to legitimize the military occupation or reassert the state’s institutional autonomy after 1967. The Likud government elected for the first time in 1977 was able to legitimize the occupation but unable to control the economy due to the lack of state autonomy and its incapacity to articulate economic interests, which became its most critical obstacle (see Chapter 6). -

Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips a Message from the Baltimore Jewish Council: TABLE of CONTENTS

Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips A Message from the Baltimore Jewish Council: TABLE OF CONTENTS The publication of this guide, Advocating for Israel: History, Tools and Tips, provides an opportunity for Introduction those who support Israel to become more involved in advocating on its behalf. It is designed for those who are becoming politically active for the first time, as well as seasoned Israel supporters. Event Timeline…………………………………………………………………………………………...2 While many people have traveled to Israel, attended lectures, and/or read about the country, there are Israel: Background…………………………………………………………………………………...….7 many who are not aware or comfortable with the process of advocacy. The purpose of this guide is to help bridge that gap. Key Words and Common Terms About Israel………………………………..………………………. 9 This guide was not created for a “one-time” event; it is a resource that can sit in your home, office, Understanding Israel’s Government…………………………...………………………………………11 classroom, or backpack and may be referred to at any time. Israel: Some Facts………………………….……………………………………………………………13 Information in this guide was developed from a variety of publications and web-based sources. We have Advocating for Israel………………...………………………………………………………...........…14 made every effort to confirm the veracity of the facts presented. Writing a Letter to Your Representative………………………………………………………………..15 To become more involved in Israel advocacy, please contact the Baltimore Jewish Council at Meeting With Officials………………………………………………………………………………….17 410-542-4850 -

“Just War” Case Study: Israeli Invasion of Lebanon

“Just War” Case Study: Israeli Invasion Of Lebanon CSC 2002 Subject Area History EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Title: “JUST WAR” CASE STUDY: ISRAELI INVASION OF LEBANON. Author: Major Christopher A. Arantz, U.S. Marine Corps Thesis: This essay examines Israel’s overall reasons for invasion of southern Lebanon, and compares them to just war theory’s war-decision law and war-conduct law. This examination will establish that Israel achieved her objectives before war termination, which lead to some unjust actions. Discussion: Between 1948 and 1982 Israel had engaged in conventional combat four times against Arab coalition forces. In all cases, Israel fought for survival of its state and established a military dominance in the region. In the years leading up to 1982, the Israeli government sought ways to eliminate security problems in its occupied territory and across its border with southern Lebanon. Israel defined its security problems as terrorist excursions that threatened the security of its people and property in northern Israel. This paper will examine Israeli conduct of deciding to go to war and their conduct of war in relation to just war theory. Three areas will be examined; 1) Did Israel have a just cause, use a legitimate authority and the right intention for invading Lebanon as in accordance with Jus ad Bellum? 2) Did Israel conduct the conflict in accordance with Jus in Bello? 3) What are the long-term ramifications for the region since the invasion? Conclusion: 1. War does not have to be just, but it clearly helps the overall outcome when world opinion believes a war is being conducted for just reasons, and clearly outlined. -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

How Popular Nonviolent Struggle Can Transform the Israeli- Palestinian Conflict

9 PEOPLE POWER IN THE HOLY LAND: HOW POPULAR NONVIOLENT STRUGGLE CAN TRANSFORM THE ISRAELI- PALESTINIAN CONFLICT Maria J. Stephan Maria J. Stephan is a Ph.D. candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University ([email protected]). The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a human tragedy that has defied political settlement for more than 50 years. Official negotiations have neither ended Israeli occupation of the Palestinian Territories nor fostered the development of a viable Palestinian state, both prerequisites for a secure peace. This article argues that an alternative strategy based on civilian-led, nonviolent struggle, or “people power,” is needed to transform the conflict. It analyzes tactics and strategies of collective nonviolent direct action and their relevance to ending a situation of occupation. Conflict theory and principles of nonviolent action are applied to a case-study analysis of the 1987 Intifada, a mostly nonviolent popular uprising that forced the issue of Palestinian statehood to the forefront. A central conclusion is that official-level negotiations are insufficient; a strategy of sustained, nonviolent direct action involving all parties, with adequate moral and material support from the international community, can help break the cycle of violence and pave the way to a just peace. Journal of Public and International Affairs, Volume 14/Spring 2003 Copyright 2003, the Trustees of Princeton University http://www.princeton.edu/~jpia I. INTRODUCTION Since 1948 a major policy goal of the United Nations (UN) and the international community has been the creation of two sovereign states, Israel and Palestine, that would coexist peacefully within internationally recognized borders. -

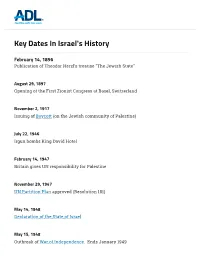

Key Dates in Israel's History

Key Dates In Israel's History February 14, 1896 Publication of Theodor Herzl's treatise "The Jewish State" August 29, 1897 Opening of the First Zionist Congress at Basel, Switzerland November 2, 1917 Issuing of BoBoBoBoyyyycottcottcottcott (on the Jewish community of Palestine) July 22, 1946 Irgun bombs King David Hotel February 14, 1947 Britain gives UN responsibility for Palestine November 29, 1947 UNUNUNUN P PPParararartitiontitiontitiontition Plan PlanPlanPlan approved (Resolution 181) May 14, 1948 DeclarationDeclarationDeclarationDeclaration of ofofof th thththeeee State StateStateState of ofofof Israel IsraelIsraelIsrael May 15, 1948 Outbreak of WWWWarararar of ofofof In InInIndependependependependendendendencececece. Ends January 1949 1 / 11 January 25, 1949 Israel's first national election; David Ben-Gurion elected Prime Minister May 1950 Operation Ali Baba; brings 113,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel September 1950 Operation Magic Carpet; 47,000 Yemeni Jews to Israel Oct. 29-Nov. 6, 1956 Suez Campaign October 10, 1959 Creation of Fatah January 1964 Creation of PPPPalestinalestinalestinalestineeee Liberation LiberationLiberationLiberation Or OrOrOrganizationganizationganizationganization (PLO) January 1, 1965 Fatah first major attack: try to sabotage Israel’s water system May 15-22, 1967 Egyptian Mobilization in the Sinai/Closure of the Tiran Straits June 5-10, 1967 SixSixSixSix Da DaDaDayyyy W WWWarararar November 22, 1967 Adoption of UNUNUNUN Security SecuritySecuritySecurity Coun CounCounCouncilcilcilcil Reso ResoResoResolutionlutionlutionlution -

Palestine History Timeline and Campaigns Calendar the History

Palestine History Timeline and Campaigns Calendar The History Timeline lays out major events in Palestinian history which student groups can choose to build educational events around, or commemorate in other ways, to build the knowledge base of their group and wider university student body. We would be available for advice on possible speakers and would love to hear what events you choose to commemorate and educate on - please let us know! We are planning to hold Palestinian historical / political webinars during the year where broad topics can be delved into and discussed more fully with experts, so keep an eye out for those! The Campaigns Calendar maps out existing international days of solidarity with Palestine. There will be events happening around the globe as thousands of people of conscience express their support for the Palestinian people on these days. By being aware of global solidarity actions we can build on integrating youth solidarity for Palestine here in the UK with its global counterparts. You might want to plan an action for your divestment campaign or maybe post a message on social media. Again, let us know what you’re planning and we can spread the word to inspire others. Over 100 Years of Palestinian History and Resistance Palestine and the Colonial Predicament, 1917-1947 Signing of the Balfour Declaration - 2 November 1917 British Mandate – 29 September 1923 – 14 May 1948 Palestinian ‘Great Revolt’ - 19 April 1936-39 UN decides to partition Palestine – 29 November 1947 ‘From Refugees to Revolutionaries’, 1948-1982 -

Unpacking the Global Campaign to Delegitimize Israel. Drawing The

SWP Research Paper Gil Murciano Unpacking the Global Campaign to Delegitimize Israel Drawing the Line between Criticism of Israel and Denying Its Legitimacy Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs SWP Research Paper 7 June 2020, Berlin Abstract ∎ In the last two decades, international delegitimization of Israel has become a new mode of operation for those denying Israel’s right to exist. It encompasses a wide range of civil-society and grassroots organizations. ∎ The campaign attempts to imitate the logic of the struggle against the South African apartheid regime – hence to undermine Israel’s inter- national legitimacy in a manner that would lead to its isolation and even- tually cause it to collapse. ∎ In its current phase, the campaign functions as a long-term effort to grad- ually change the discourse and mindset of Israel’s critics in the West. Its main goal is to mainstream delegitimization – hence to reposition anti- Zionism from the radical margins into the mainstream of Western liberal- progressive circles, with specific emphasis on critics of Israel’s policies. ∎ A key strategy to mainstream delegitimization is to blur the differences between criticism of Israeli policy and challenges to Israel’s basic legiti- macy. This includes efforts to turn items of the delegitimization agenda into an integral part of the political debate about Israel. ∎ As a result, many critics of Israel’s policies end up supporting efforts that are led by the delegitimization campaign. The discussion in the West on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is gradually developing into a dichotomous encounter between supporting Israel and its policies unquestioningly or supporting anti-Zionism. -

Israel - Palestine Conflict - a Tale of Grave Human Violations & Innumerable Casualties

RESEARCH PAPER Law Volume : 4 | Issue : 9 | September 2014 | ISSN - 2249-555X Israel - Palestine Conflict - A Tale of Grave Human Violations & Innumerable Casualties KEYWORDS Mr.Manish Dalal Mr.ArunKumar Singh Assistant Professor in Law Noida International First year, Faculty of Law, Noida International University University * Corresponding author ABSTRACT Israel - Palestine conflict is one of the most burning issues of modern times which poses a big threat to international peace & security. This conflict is an example of grave human rights violations & a large no. of human causalities’. The warring sides are the Israeli government on the one hand and a group named Hamas which is controlling Gaza Strip after winning the elections in 2006 on the other hand. Hamas is mostly viewed as a terrorist organization all over the world. Both Israel & Hamas do not recognize each other's authority & ready to use violence to achieve their means. But to understand the reasons for this conflict one has to go back to history in the middle of 20th century where it all started. Introduction The First Palestinian Intifada The history of this war dates back to the year 1948 with The First Palestinian Intifada also known as a the first Pal- the declaration of State of Israel on 15th May, 1948 which estinian uprising against the Israeli occupation began on didn’t go down well with the Arab League which pro- 8th December, 1987 & ended on 13th September, 1993 claimed that the entire area given to Israel belongs to with the signing of Oslo Accords. It was the first biggest them & it didn’t recognize Israel as a State giving rise to uprising against Israel after their 1967 occupation of the 1948 Arab-Israel war in which many people lost their lives disputed territory of Gaza Strip, West Bank & East Jerusa- & many more became refugees. -

Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict∗

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/12/48 25 September 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Twelfth session Agenda item 7 HUMAN RIGHTS IN PALESTINE AND OTHER OCCUPIED ARAB TERRITORIES Report of the United Nations Fact-Finding Mission on the Gaza Conflict∗ ∗ Late submission. GE.09-15866 A/HRC/12/48 page 2 CONTENTS Paragraphs Page Acronyms and abbreviations .......................................................................................... 11 Executive summary .............................................................................. 1-130 13 PART ONE: METHODOLOGY, CONTEXT AND APPLICABLE LAW INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 131-150 37 I. METHODOLOGY ............................................................... 151-175 41 A. Mandate and terms of reference ................................. 151-155 41 B. Methods of work ......................................................... 156-167 42 C. Assessment of information ......................................... 168-172 44 D. Consultation with the parties ...................................... 173-175 45 II. CONTEXT............................................................................. 176-222 46 A. Historical context......................................................... 177-197 46 B. Overview of Israel’s pattern of policies and conduct relevant to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, and links between the situation in Gaza and in the West Bank...................................... 198-209