The Problems of Preserving the Language and Culture of the Selkups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cassidy Code

2019 THE CASSIDY CODE ZAHMOUL, Noureddine ABD/USA/США ABSTRACT Awareness about Basic Guttural Consonants, BGC, perdurable presence, since illo-tempore, in Hamito-Semitic languages, and conspicuous absence among Indo-European and Uralic languages, raises a case of interest. Tunsi Long Range Comparison, LRC, with the English and the Suomi languages entails discovery of regular differences, alternations, and reversal patterns hidden in the data. A brand new approach emerges facilitating languages LRC, and easing Language Origins Research, LOR. My first claim is about an unvoiced consonant gamut available to ofset eache missing BGC. My second claim covers the useful, notrivial, unobtrusive orijinal consonantal reversal phenomenon. The Cassidy Code is Sumerian. Grimm and Verner Laws sequel, alternating BGS with mostly unvoiced consonants or apocope entailing a forward shift of articulation basis, due finer pronunciation, and adding the tran mogrifying reversals. The idea is to put forward a paralel code, in LRC of language and LOR quest, to the focus on separate wide swaths of straight cognations. Key Words: Cassidy code, Sumerian, Language Origins Research (LOR), Basic Guttural Consonants (BGC), Long Range Comparison (LRC), Indo- European languages, Uralic languages. 2020 2021 2022 2023 Annex I: The Precession and the Forgotten Ice Age Jane B. Sellers sought during her sixty years of research to assess and demonstrate that: “Archeologists, by and large, lack an understanding of the precession and this affects their conclusions concerning ancient myths, ancient gods and ancient temple alignments. Philologists, too, ignore the accusation that certain problems are not going to be solved as long as they imagine that familiarity with grammar replaces scientific knowledge of astronomy. -

Russia and Siberia: the Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People Into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and It’S Consequences

The Aoyama Journal of International Politics, Economics and Communication, No. 106, May 2021 CCCCCCCCC Article CCCCCCCCC Russia and Siberia: The Beginning of the Penetration of Russian People into Siberia, the Campaign of Ataman Yermak and it’s Consequences Aleksandr A. Brodnikov* Petr E. Podalko** The penetration of the Russian people into Siberia probably began more than a thousand years ago. Old Russian chronicles mention that already in the 11th century, the northwestern part of Siberia, then known as Yugra1), was a “volost”2) of the Novgorod Land3). The Novgorod ush- * Associate Professor, Novosibirsk State University ** Professor, Aoyama Gakuin University 1) Initially, Yugra was the name of the territory between the mouth of the river Pechora and the Ural Mountains, where the Finno-Ugric tribes historically lived. Gradually, with the advancement of the Russian people to the East, this territorial name spread across the north of Western Siberia to the river Taz. Since 2003, Yugra has been part of the offi cial name of the Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug: Khanty-Mansiysk Autonomous Okrug—Yugra. 2) Volost—from the Old Russian “power, country, district”—means here the territo- rial-administrative unit of the aboriginal population with the most authoritative leader, the chief, from whom a certain amount of furs was collected. 3) Novgorod Land (literally “New City”) refers to a land, also known as “Gospodin (Lord) Veliky (Great) Novgorod”, or “Novgorod Republic”, with its administrative center in Veliky Novgorod, which had from the 10th century a tendency towards autonomy from Kiev, the capital of Ancient Kievan Rus. From the end of the 11th century, Novgorod de-facto became an independent city-state that subdued the entire north of Eastern Europe. -

Chronology of Stalin's Life

Chronology of Stalin's Life ('Old Style' to February 1918) 1879 9 Dec Born in Gori. 1888 Sept Enters clerical elementary school in Gori. 1894 Sept Enters theological seminary in Tbilisi. 1899 May Expelled from seminary. 1900 Apr Addresses worker demonstration near Tbilisi. 1902 Apr Arrested in Batumi following worker demonstration of which he was an organizer. 1903 July-Aug Appearance of Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Congress of the Russian Social-Democratic Workers' Party (Stalin not present). 1904 Jan Escapes from place of exile in Siberia and returns to underground revolutionary work in Transcaucasia. 1905 Revolution, reaching peak in Oct-Dec. threatens the survival of the tsarist government. Stalin marries Ekaterina Svanidze. Dec Attends Bolshevik conference. also attended by Lenin, in Tammerfors, Finland. 1906 Apr Attends 'Unity' congress of party in Stockholm. 1907 Mar Birth of first child, Yakov. Apr Publishes first substantial piece of writing, 'Anarchism or Socialism?' Apr-May Attends party congress in London. Jun Moves operations to Baku. Oct Death of his wife, Ekaterina. 1908 Mar Arrested in Baku. 317 318 Chronology of Stalin's Life 1909 June Escapes from place of exile, Solvychegodsk, returns to underground in Baku. 1910 Mar Arrested and jailed. Oct Returned to exile in Solvychegodsk. 1911 June Police permit his legal residence in Vologda. Sept Illegally goes to St Petersburg but is arrested and returned to Vologda. 1912 Jan Bolshevik conference in Prague at which Lenin attempts to establish his control of party; Stalin not present but soon after is co-opted to new Central Committee. Apr Illegally moves to St Petersburg, but is arrested there. -

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin

Defining Territories and Empires: from Mongol Ulus to Russian Siberia1200-1800 Stephen Kotkin (Princeton University) Copyright (c) 1996 by the Slavic Research Center All rights reserved. The Russian empire's eventual displacement of the thirteenth-century Mongol ulus in Eurasia seems self-evident. The overthrow of the foreign yoke, defeat of various khanates, and conquest of Siberia constitute core aspects of the narratives on the formation of Russia's identity and political institutions. To those who disavow the Mongol influence, the Byzantine tradition serves as a counterweight. But the geopolitical turnabout is not a matter of dispute. Where Chingis Khan and his many descendants once held sway, the Riurikids (succeeded by the Romanovs) moved in. *1 Rather than the shortlived but ramified Mongol hegemony, which was mostly limited to the middle and southern parts of Eurasia, longterm overviews of the lands that became known as Siberia, or of its various subregions, typically begin with a chapter on "pre-history," which extends from the paleolithic to the moment of Russian arrival in the late sixteenth, early seventeenth centuries. *2 The goal is usually to enable the reader to understand what "human material" the Russians found and what "progress" was then achieved. Inherent in the narratives -- however sympathetic they may or may not be to the native peoples -- are assumptions about the historical advance deriving from the Russian arrival and socio-economic transformation. In short, the narratives are involved in legitimating Russia's conquest without any notion of alternatives. Of course, history can also be used to show that what seems natural did not exist forever but came into being; to reveal that there were other modes of existence, which were either pushed aside or folded into what then came to seem irreversible. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

[.35 **Natural Language Processing Class Here Computational Linguistics See Manual at 006.35 Vs

006 006 006 DeweyiDecimaliClassification006 006 [.35 **Natural language processing Class here computational linguistics See Manual at 006.35 vs. 410.285 *Use notation 019 from Table 1 as modified at 004.019 400 DeweyiDecimaliClassification 400 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 [400 [400 *‡Language Class here interdisciplinary works on language and literature For literature, see 800; for rhetoric, see 808. For the language of a specific discipline or subject, see the discipline or subject, plus notation 014 from Table 1, e.g., language of science 501.4 (Option A: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, class in 410, where full instructions appear (Option B: To give local emphasis or a shorter number to a specific language, place before 420 through use of a letter or other symbol. Full instructions appear under 420–490) 400 DeweyiDecimali400Classification Language 400 SUMMARY [401–409 Standard subdivisions and bilingualism [410 Linguistics [420 English and Old English (Anglo-Saxon) [430 German and related languages [440 French and related Romance languages [450 Italian, Dalmatian, Romanian, Rhaetian, Sardinian, Corsican [460 Spanish, Portuguese, Galician [470 Latin and related Italic languages [480 Classical Greek and related Hellenic languages [490 Other languages 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [401 *‡Philosophy and theory See Manual at 401 vs. 121.68, 149.94, 410.1 401 DeweyiDecimali401Classification Language 401 [.3 *‡International languages Class here universal languages; general -

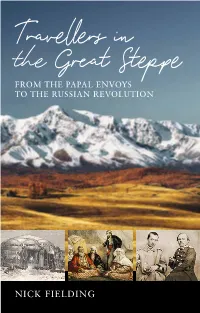

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

Bylye Gody. 2019. Vol. 52. Is. 2

Bylye Gody. 2019. Vol. 52. Is. 2 Copyright © 2019 by International Network Center for Fundamental and Applied Research Copyright © 2019 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. Published in the USA Co-published in the Slovak Republic Bylye Gody Has been issued since 2006. E-ISSN: 2310-0028 Vol. 52. Is. 2. pp. 470-481. 2019 DOI: 10.13187/bg.2019.2.470 Journal homepage: http://ejournal52.com The First “Fortified Town of Narym”: the Problem of Localization and Search Prospects Eugeniy V. Barsukov a , * а National Research Tomsk State University, Russian Federation Abstract “Russian archeology” is a trend that is becoming increasingly popular in Siberia. Of particular interest is the period of the initial colonization of Siberia. In the Middle Ob region it is known more than a dozen towns and forts, founded at the end of the XVI and in the XVII century. Three of them – Narym, Ket, Kungop were located on the banks of the Ket river, the vast basin of which connected Western and Eastern Siberia in the XVII-XVIII centuries. The circumstances and even the foundation dates of these fortified points due to the lack of sources are reconstructed with great difficulty. The Narym fortified town, which became the forerunner and the most important strategic point of the Russian development of the Narym Territory, has been "forgotten" by historians in recent decades. This is due to the limited available written sources, the overwhelming majority of which were introduced into scientific circulation by G.F. Mueller and P.N. Butsinsky. Although the potential for expanding the “written” base has not been drained, the most promising is the shift of emphasis towards local-historical and local-geographical research, based on a comprehensive analysis of sources of different types, including usage of the archaeological experience of studying the Russian time objects. -

Resilient Russian Women in the 1920S & 1930S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Zea E-Books Zea E-Books 8-19-2015 Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s Marcelline Hutton [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook Part of the European Languages and Societies Commons, Modern Art and Architecture Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Russian Literature Commons, Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hutton, Marcelline, "Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s" (2015). Zea E-Books. Book 31. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/zeabook/31 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Zea E-Books at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Zea E-Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Marcelline Hutton Resilient Russian Women in the 1920s & 1930s The stories of Russian educated women, peasants, prisoners, workers, wives, and mothers of the 1920s and 1930s show how work, marriage, family, religion, and even patriotism helped sustain them during harsh times. The Russian Revolution launched an economic and social upheaval that released peasant women from the control of traditional extended fam- ilies. It promised urban women equality and created opportunities for employment and higher education. Yet, the revolution did little to elim- inate Russian patriarchal culture, which continued to undermine wom- en’s social, sexual, economic, and political conditions. Divorce and abor- tion became more widespread, but birth control remained limited, and sexual liberation meant greater freedom for men than for women. The transformations that women needed to gain true equality were post- poned by the pov erty of the new state and the political agendas of lead- ers like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. -

The Irish Language in Education in Northern Ireland

The Irish language in education in Northern Ireland European Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning hosted by IRISH The Irish language in education in Northern Ireland | 3rd Edition | c/o Fryske Akademy Doelestrjitte 8 P.O. Box 54 NL-8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands T 0031 (0) 58 - 234 3027 W www.mercator-research.eu E [email protected] | Regional dossiers series | tca r cum n n i- ual e : Available in this series: This document was published by the Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Ladin; the Ladin language in education in Italy (2nd ed.) and Language Learning with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the Province Latgalian; the Latgalian language in education in Latvia of Fryslân. Lithuanian; the Lithuanian language in education in Poland Maltese; the Maltese language in education in Malta Manx Gaelic; the Manx Gaelic language in education in the Isle of Man Meänkieli and Sweden Finnish; the Finnic languages in education in Sweden © Mercator European Research Centre on Multilingualism Nenets, Khanty and Selkup; The Nenets, Khanty and Selkup language in education and Language Learning, 2019 in the Yamal Region in Russia North-Frisian; the North Frisian language in education in Germany (3rd ed.) ISSN: 1570 – 1239 Occitan; the Occitan language in education in France (2nd ed.) 3rd edition Polish; the Polish language in education in Lithuania Romani and Beash; the Romani and Beash languages in education in Hungary The contents of this dossier may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, Romansh: The Romansh language in education in Switzerland provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to the Mercator European Sami; the Sami language in education in Sweden Research Centre on Multilingualism and Language Learning. -

S E L K U P M Y T H O L O G Y

S e l k u p M y t h o l o g y ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF URALIC MYTHOLOGIES 4 Editors-in-Chief Anna-Leena Siikala (Helsinki) Vladimir Napolskikh (Izhevsk) Mihály Hoppál (Budapest) Editorial board Veikko Anttonen Marjorie Mandelstam Balzer Kirill V. Chistov Pekka Hakamies Nikolaĭ D. Konakov Vyacheslav M. Kulemzin Mare Kõiva Nikolaĭ F. Mokshin Håkan Rydving Aleksandr I. Teryukov Nataliya Tuchkova Academy of Finland Helsinki University Department of Folklore Studies Russian Academy of Sciences Hungarian Academy of Sciences Ethnographical Institute S e l k u p M y t h o l o g y AUTHORS NATALYA A. TUCHKOVA ARIADNA I. KUZNETSOVA, OLGA A. KAZAKEVICH, ALEKSANDRA A. KIM-MALONI, SERGEI V. GLUSHKOV, ALEKSANDRA V. BAĬDAK EDITORS VLADIMIR NAPOLSKIKH ANNA-LEENA SIIKALA MIHÁLY HOPPÁL AKADÉMIAI KIADÓ BUDAPEST FINNISH LITERATURE SOCIETY HELSINKI This edition is based on the Russian original Anna-Leena Siikala, Vladimir Napolskikh, Mihály Hoppál (red.): Ėntsiklopediya ural’skik mifologiĭ. Tom IV. Mifologiya Sel’kupov.Rukovoditel’ avtorskogo kollektiva N. A. Tuchkova. Avtorskiĭ kollektiv: A. I. Kuznetsova, O. A. Kazakevich, N. A. Tuchkova, A. A. Kim-Maloni, S. B. Glushkov, A. V. Baĭdak. Nauchnyĭ redaktor V. V. Napol’skikh. Tomsk: Tomskiĭ gosudarstvenniĭ pedagogicheskiĭ universitet, Tomskiĭ oblastnoĭ kraevedcheskiĭ muzeĭ, Moskocskiĭ gosudarstvenniĭ universitet, Institut yazykoznaniya RAN. Edited by Vladimir Napolskikh, Anna-Leen Siikala and Mihály Hoppál Translated by Sergei Glushkov Translation revised by Clive Tolley ISBN ISSN © Authors, 2007 © Editors, 2007 © Translation, 2007 Publishesd by Akadémiai Kiadó in collaboration with Finnish Literature Society P.O. Box 245, H-1519 Budapest, Hungary www.akkrt.hu All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means or transmitted or translated into machine language without the written permission of the publisher and the authors. -

Sketches of Russian Mires / Streiflichter Auf Die Moore Russlands 255- 321 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Stapfia Jahr/Year: 2005 Band/Volume: 0085 Autor(en)/Author(s): Minayeva T., Sirin A. Artikel/Article: Sketches of Russian Mires / Streiflichter auf die Moore Russlands 255- 321 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Sketches of Russian Mires Edited by T. MINAYEVA & A. SIRIN Introduction and low destruction on the other (high hu- midity, but low temperature). This situation Russia is not commonly associated with is typical for Russia's boreal zone, where, in mires. In countries such as Finland or Ire- some regions, mires cover over 50% of the land, mires cover a greater proportion of the land surface (Fig. 1). All possible combina- country's territory and play a more signifi- tions of geomorphologic, climatic, and pale- cant role in its social and economic life. In ogeorgaphic factors across the territory of Russia, mires cover about 8% of the coun- Russia, the world's largest country, result in try's area, and, together with paludified great variation of mire types. lands, account for 20% of its territory (VOM- Mires became a part of land use and cul- PERSKY et al. 1999). However, there are few ture in many regions, and objects of thor- places in the world where one finds such a ough interest for different branches of sci- high diversity of mire types and biogeo- ence. Knowledge of mires in Russia was ini- graphical variations. tiated by German and Dutch experience Mire distribution is distinctly connected (Peatlands of Russia ..