Environmental Change and Human Activity Through the Late Pleistocene Into the Holocene in the Highlands of New Guinea: a Scenario

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, Port Macquarie Region

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. FOREST RESOURCES SERIES NO. 19 FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS BY ALAN YORK \ \ FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES ----------------------------- FAUNA SURVEY, WINGHAM MANAGEMENT AREA, PORT MACQUARIE REGION PART 1. MAMMALS by ALAN YORK FOREST ECOLOGY SECTION WOOD TECHNOLOGY AND FOREST RESEARCH DIVISION FORESTRY COMMISSION OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY 1992 Forest Resources Series No. 19 March 1992 The Author: AIan York, BSc.(Hons.) PhD., Wildlife Ecologist, Forest Ecology Section, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales. Published by: Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales, Wood Technology and Forest Research Division, 27 Oratava Avenue, West Pennant Hills, 2125 P.O. Box lOO, Beecroft 2119 Australia. Copyright © 1992 by Forestry Commission ofNew South Wales ODC 156.2:149 (944) ISSN 1033-1220 ISBN 07305 5663 8 Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, -i- PortMacquarie Region Part 1. Mammals TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 1. The Wingham Management Area 1 (a) Location 1 (b) Physical environment 3 (c) Vegetation communities 3 (d) Fire 5 (e) Timber harvesting : 5 SURVEY METHODOLOGy 7 1. Overall Sampling Strategy 7 (a) General survey 7 (b) Plot-based survey 7 (i) Stratification 1:Jy Broad Forest Type : 8 (ii) Stratification by Altitude 8 (iii) Stratification 1:Jy Management History 8 (iv) Plot selection 9 (v) Special considerations 9 (vi) Plot establishment 10 (vii) Plot design........................................................................................................... -

The Lives of Creatures Obscure, Misunderstood, and Wonderful: a Volume in Honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019

Papers in Honour of Ken Aplin edited by Julien Louys, Sue O’Connor and Kristofer M. Helgen Helgen, Kristofer M., Julien Louys, and Sue O’Connor. 2020. The lives of creatures obscure, misunderstood, and wonderful: a volume in honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019 ..........................149 Armstrong, Kyle N., Ken Aplin, and Masaharu Motokawa. 2020. A new species of extinct False Vampire Bat (Megadermatidae: Macroderma) from the Kimberley Region of Western Australia ........................................................................................................... 161 Cramb, Jonathan, Scott A. Hocknull, and Gilbert J. Price. 2020. Fossil Uromys (Rodentia: Murinae) from central Queensland, with a description of a new Middle Pleistocene species ............................................................................................................. 175 Price, Gilbert J., Jonathan Cramb, Julien Louys, Kenny J. Travouillon, Eleanor M. A. Pease, Yue-xing Feng, Jian-xin Zhao, and Douglas Irvin. 2020. Late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of the Broken River karst area, northern Queensland, Australia ........................ 193 Theden-Ringl, Fenja, Geoffrey S. Hope, Kathleen P. Hislop, and Benedict J. Keaney. 2020. Characterizing environmental change and species’ histories from stratified faunal records in southeastern Australia: a regional review and a case study for the early to middle Holocene ........................................................................................... 207 Brockwell, Sally, and Ken Aplin. 2020. Fauna on -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 57: 341-350 (1999). The Pleistocene mammal fauna of Kelangurr Cave, central montane Irian Jaya, Indonesia Timothy F. Flannery Mammalogy, Australian Museum, 6 College St, Sydney, NSW 2000; email: [email protected] Abstract - Sixteen mammal taxa have been identified on craniodental material from a rich deposit of bones in the first chamber of Kelangurr Cave. The remains of all species except the largest (Maokopia ronaldi and Protemnodon hopei) and the smallest (Miniopterus sp. cf. M. macrocneme) and possibly a single tooth cap of Anisomys imitator, are considered to have been accumulated by Pleistocene Sooty Owls (Tyto tenebricosa). About a dozen bird bones representing species ranging in size from finch to medium-sized honeyeater, and currently unidentifiable, are the only non-mammalian remains from the deposit. Kelangurr Cave is at an elevation of 2,950 m, and presently located in tall upper montane forest. Analysis of the habitat requirements of the fossil mammal fauna indicates that at the time of deposition (25-20,000 BP) the cave was surrounded by alpine tussock grassland and scrub similar to that occurring today at 4,000-4,200 m on Mt Carstensz and Mt Wilhelmina. The age of faunal remains not accumulated by owls is uncertain. There is no evidence of non-analogue mammal communities, and no evidence of extinction among species under 2 kg in weight in the fauna. INTRODUCTION Mission during or before the 1980s. In January 1990 The Kwiyawagi area (Figure 1) is the only part of Or Geoffrey Hope walked in to the West Baliem Irian Jaya that has proved to be rich in Pleistocene valley from Wamena, and found bones to be vertebrate fossils (Flannery 1994). -

On the Evolution of Kangaroos and Their Kin (Family Macropodidae) Using Retrotransposons, Nuclear Genes and Whole Mitochondrial Genomes

ON THE EVOLUTION OF KANGAROOS AND THEIR KIN (FAMILY MACROPODIDAE) USING RETROTRANSPOSONS, NUCLEAR GENES AND WHOLE MITOCHONDRIAL GENOMES William George Dodt B.Sc. (Biochemistry), B.Sc. Hons (Molecular Biology) Principal Supervisor: Dr Matthew J Phillips (EEBS, QUT) Associate Supervisor: Dr Peter Prentis (EEBS, QUT) External Supervisor: Dr Maria Nilsson-Janke (Senckenberg Biodiversity and Research Centre, Frankfurt am Main) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Science and Engineering Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 1 Keywords Adaptive radiation, ancestral state reconstruction, Australasia, Bayesian inference, endogenous retrovirus, evolution, hybridization, incomplete lineage sorting, incongruence, introgression, kangaroo, Macropodidae, Macropus, mammal, marsupial, maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony, molecular dating, phylogenetics, retrotransposon, speciation, systematics, transposable element 2 Abstract The family Macropodidae contains the kangaroos, wallaroos, wallabies and several closely related taxa that occupy a wide variety of habitats in Australia, New Guinea and surrounding islands. This group of marsupials is the most species rich family within the marsupial order Diprotodontia. Despite significant investigation from previous studies, much of the evolutionary history of macropodids (including their origin within Diprotodontia) has remained unclear, in part due to an incomplete early fossil record. I have utilized several forms of molecular sequence data to shed -

Of the Early Pleistocene Nelson Bay Local Fauna, Victoria, Australia

Memoirs of Museum Victoria 74: 233–253 (2016) Published 2016 ISSN 1447-2546 (Print) 1447-2554 (On-line) http://museumvictoria.com.au/about/books-and-journals/journals/memoirs-of-museum-victoria/ The Macropodidae (Marsupialia) of the early Pleistocene Nelson Bay Local Fauna, Victoria, Australia KATARZYNA J. PIPER School of Geosciences, Monash University, Clayton, Vic 3800, Australia ([email protected]) Abstract Piper, K.J. 2016. The Macropodidae (Marsupialia) of the early Pleistocene Nelson Bay Local Fauna, Victoria, Australia. Memoirs of Museum Victoria 74: 233–253. The Nelson Bay Local Fauna, near Portland, Victoria, is the most diverse early Pleistocene assemblage yet described in Australia. It is composed of a mix of typical Pleistocene taxa and relict forms from the wet forests of the Pliocene. The assemblage preserves a diverse macropodid fauna consisting of at least six genera and 11 species. A potentially new species of Protemnodon is also possibly shared with the early Pliocene Hamilton Local Fauna and late Pliocene Dog Rocks Local Fauna. Together, the types of species and the high macropodid diversity suggests a mosaic environment of wet and dry sclerophyll forest with some open grassy areas was present in the Nelson Bay area during the early Pleistocene. Keywords Early Pleistocene marsupials, Macropodinae, Nelson Bay Local Fauna, Australia, Protemnodon, Hamilton Local Fauna. Introduction Luckett (1993) and Luckett and Woolley (1996). All specimens are registered in the Museum Victoria palaeontology collection The Macropodoidea (kangaroos and relatives) are one of the (prefix NMV P). All measurements are in millimetres. most conspicuous elements of the Australian fauna and are often also common in fossil faunas. -

Download Full Article 1.5MB .Pdf File

https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1973.34.03 9 May 1973 FOSSIL VERTEBRATE FAUNAS FROM THE LAKE VICTORIA REGION, S.W. NEW SOUTH WALES, AUSTRALIA By Larry G. Marshall Zoology Department, Monash University, Victoria* Abstract Fossil vertebrate localities and faunas in the Lake Victoria region of S.W. New South Wales, Australia, are described. The oldest fossil bearing deposit, the late Pliocene or early Pleistocene Moorna Formation and associated Chowilla Sand have yielded specimens of Neoceratodus sp., Emydura macquarrii, several species of small dasyurid, specimens of Glaucodon cf. G. ballaratensis, a species of Protemnodon which compares closely with P. cf. P. otibandus from the late Pliocene or early Pleistocene Chinchilla Sand in SE. Queensland, specimens of Lagostrophus cf L. fasciatus, species of Petrogale, Macropus, Osphranter, Sthenurus, Bettongia, Diprotodon, Lasiorhinus, a peramelid, at least two species of pseudomyine rodents and a species of Rattus cf. R. lutreolus. It is shown that the holotype of Zygomaturus victoriae (Owen) 1872 may have been collected from these sediments. The late Pliocene or early Pleistocene Blanchetown Clay has yielded species of Neoceratodus, Thylacoleo, Phas- colonus, Bettongia, Sthenurus, a diprotodontid, and a rodent. The late Pleistocene Rufus Formation has yielded species of Dasycercus, Sarcophilus, Thylacinus, Phascolonus, Lasiorhinus, Bettongia, Procoptodon, Onychogalea, Macropus, and Leporillus. A large species of macropod and a species of Phascolonus were collected from the late Pleistocene Monoman Formation. The lunette on the E. side of Lake Victoria has yielded a large, diverse fauna of late Pleistocene —Holocene age, that includes such extinct species as Protemnodon anak, P. brehus, Procoptodon goliah, Sthenurus andersoni, S. -

Longevity Survey

LONGEVITY SURVEY LENGTH OF LIFE OF MAMMALS IN CAPTIVITY AT THE LONDON ZOO AND WHIPSNADE PARK The figures given in the following tables are based on the records of the Zoological Society of London for the years 1930 to 1960. The number of specimens in each sample is given in the first column. The percentage of the sample that died in less than a year at the zoo is iven in second column. In this way ‘delicate’ zoo species can be noted at a glance. An average fife span of all those individuals living for more than a year at the zoo is given (in months) in the third column. In the fourth column the maximum individual life-span is noted for each species. It must be emphasized that the age of specimens arriving at the zoo is seldom known accur- ately and no allowance has been made for this. All figures refer to the period of time between arrival at the zoo and death at the zoo. Actual life-spans will, therefore, usually be longer than those given. Number o % dead in Average age Ma.life individual less than (in nronths) span in sample 12 month of those (in months) livi 12 man% or longer ORDER MONOTREMATA Tachyglossus aculeatirs Echidna 7 I00 10 Zuglossus bruijni Druijns Echidna 2 - 368 ORDER MARSUPIALIA Caluromys philander Philander Opossum 3 - 50 Philander opossum Quica Opossum I - 1s Lutreolina crussicaudufa Thick-tailed Opossum 6 50 1s Metachirus nudicuudatirs Rat-tailed Opossum 14 71 27 Didelphis marsupialis Virginian Opossum 34 82 26 Didelphis azarae Azara’s Opossuni IS 53 48 Dmyurus uiuerrinus Little Native Cat 2 I00 I1 Dasyurus maculatus -

Monotremes Bibliography

Calaby’s Monotreme Literature Abensperg-Traun, M.A. (1988). Food preference of the echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae), in the wheatbelt of Western Australia. Australian Mammalogy 11: 117–123. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M. (1989). Some observations on the duration of lactation and movements of a Tachyglossus aculeatus acanthion (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae) from Western Australia. Australian Mammalogy 12: 33–34. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M. (1991). A study of home range, movements and shelter use in adult and juvenile echidnas, Tachyglossus aculeatus (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae), in Western Australian wheatbelt reserves. Australian Mammalogy 14: 13–21. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M. (1991). Survival strategies of the echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae). Biological Conservation 58: 317–328. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M. (1994). Blindness and survival in free-ranging echidnas, Tachyglossus aculeatus. Australian Mammalogy 17: 11 7– 119. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M. and De Boer, E.S. (1992). The foraging ecology of a termite- and ant-eating specialist, the echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae). Journal of Zoology, London 226: 243–257. Monotremes Abensperg-Traun, M., Dickman, C.R. and De Boer, E.S. (1991). Patch use and prey defence in a mammalian myrmecophage, the echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus) (Monotremata: Tachyglossidae): a test of foraging efficiency in captive and free-ranging animals. Journal of Zoology, London 225: 481–493. Monotremes Adamson, S. and Campbell, G. (1988). The distribution of 5–hydroxytryptamine in the gastrointestinal tract of reptiles, birds and a prototherian mammal. An immunohistochemical study. Cell and Tissue Research 251: 633–639. Monotremes Aitken, P.F. (1969). The mammals of the Flinders Ranges. Pp. 255–356 in Corbett, D.W.P. -

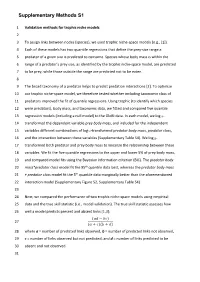

Supplementary Methods S1

1 Validation methods for trophic niche models 2 3 To assign links between nodes (species), we used trophic niche-space models (e.g., [1]). 4 Each of these models has two quantile regressions that define the prey-size range a 5 predator of a given size is predicted to consume. Species whose body mass is within the 6 range of a predator’s prey size, as identified by the trophic niche-space model, are predicted 7 to be prey, while those outside the range are predicted not to be eaten. 8 9 The broad taxonomy of a predator helps to predict predation interactions [2]. To optimize 10 our trophic niche-space model, we therefore tested whether including taxonomic class of 11 predators improved the fit of quantile regressions. Using trophic (to identify which species 12 were predators), body mass, and taxonomic data, we fitted and compared five quantile 13 regression models (including a null model) to the GloBI data. In each model, we log10- 14 transformed the dependent variable prey body mass, and included for the independent 15 variables different combinations of log10-transformed predator body mass, predator class, 16 and the interaction between these variables (Supplementary Table S4). We log10- 17 transformed both predator and prey body mass to linearize the relationship between these 18 variables. We fit the five quantile regressions to the upper and lower 5% of prey body mass, 19 and compared model fits using the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). The predator body 20 mass*predator class model fit the 95th quantile data best, whereas the predator body mass 21 + predator class model fit the 5th quantile data marginally better than the aforementioned 22 interaction model (Supplementary Figure S2, Supplementary Table S4). -

Downloaded from Bioscientifica.Com at 10/10/2021 09:01:50PM Via Free Access 174 R

MORPHOLOGICAL STUDIES ON IMPLANTATION IN MARSUPIALS R. L. HUGHES School of Zoology, University of New South Wales, P.O. Box 1, Kensington, New South Wales 2033, Australia This paper reviews some of the more important literature relating to the morphological aspects of marsupial implantation in conjunction with hitherto unpublished observations. The data, although fragmentary, are derived from a wide variety of marsupial species and are presented in support of the thesis that fetal-maternal relationships in marsupials can most appropriately be divided into two phases. The first phase occupies up to two-thirds or more of pregnancy while the blastocyst undergoes expansion. The three primary germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm) are established and embryonic development proceeds at least as far as the pre-fetal or early fetal stage. Im- plantation is not known to occur in any marsupial during this period as an intact shell membrane completely separates fetal and maternal tissues. The second phase begins during the terminal third of gestation and is initiated by the rupture of the shell membrane. This is the period when almost all fetal differentiation occurs, and in only some marsupials does the trophoblast exhibit invasive properties that result in either a rudimentary implantation or, in one group (the Peramelidae), a relatively typical implantation reminiscent of that found in eutherian mammals. The details of the morphological events during the first and second phases of marsupial development will now be considered separately. Although the photomicrographs and much of the accompanying text are concerned with only three marsupials, Trichosurus vulpécula (brush possum), Phascolarctos cinereus (koala) and Perameles nasuta (bandicoot), they are considered to provide an adequate coverage of the range of fetal-maternal adaptation relating to im¬ plantation in marsupials as a whole. -

A New Species of <I>Sthenurus</I> (Marsupialia, Macropodidae)

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Marcus, Leslie F., 1962. A new species of Sthenurus (Marsupialia, Macropodidae) from the Pleistocene of New South Wales: a contribution from the Museum of Palaeontology, University of California, U.S.A. Records of the Australian Museum 25(14): 299–304. [22 November 1962]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.25.1962.666 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia VOL. XXV, No. 14 SYDNEY, 22 NOVEMBER, 1962 RECORDS of The Australian Museum (World List abbreviation: Rec. Anst. Mns.) Printed by order of the Trustees Edited by the Director, J. W. EVANS, Sc.D. A New Species of Sthenurus (Marsupialia, Macropodidae) from the Pleistocene of New South Wales By LESLIE F. MARCUS Pages 299-304 Fig. 1 Registered at" the General Post Office, Sydney, for transmission by post as a periodical G33714 299 A New Species of (Marsupialia, Macropodidae) from Pleistocene of South Wales A contribution from the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, U.S.A. By LESLlE F. MARCUS Assistant Professor, Department of Statistics, Kansas State University, U.S.A. (Fig. I) Manuscript received 5.6.62 ABSTRACT A new species of Sthenurus, Sthenurus andersoni, is described from the P1eistocene Bingara fauna of New South Wales, Australia. The holotype is a left mandible, lacking the ascending ramus. Fourteen paratypes and three referred specimens were also used in the description. S. andersoni appears to be closely related to S. atlas. INTRODUCTION The genus Sthenurus is represented by three species in the Bingara fauna from Murchison County, New South Wales, Australia (Marcus, 1962, unpublished Ph.