Fauna Survey, Wingham Management Area, Port Macquarie Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

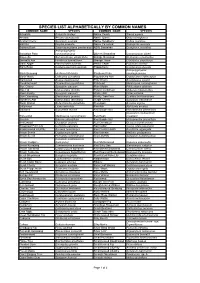

Species List Alphabetically by Common Names

SPECIES LIST ALPHABETICALLY BY COMMON NAMES COMMON NAME SPECIES COMMON NAME SPECIES Actephila Actephila lindleyi Native Peach Trema aspera Ancana Ancana stenopetala Native Quince Guioa semiglauca Austral Cherry Syzygium australe Native Raspberry Rubus rosifolius Ball Nut Floydia praealta Native Tamarind Diploglottis australis Banana Bush Tabernaemontana pandacaqui NSW Sassafras Doryphora sassafras Archontophoenix Bangalow Palm cunninghamiana Oliver's Sassafras Cinnamomum oliveri Bauerella Sarcomelicope simplicifolia Orange Boxwood Denhamia celastroides Bennetts Ash Flindersia bennettiana Orange Thorn Citriobatus pauciflorus Black Apple Planchonella australis Pencil Cedar Polyscias murrayi Black Bean Castanospermum australe Pepperberry Cryptocarya obovata Archontophoenix Black Booyong Heritiera trifoliolata Picabeen Palm cunninghamiana Black Wattle Callicoma serratifolia Pigeonberry Ash Cryptocarya erythroxylon Blackwood Acacia melanoxylon Pink Cherry Austrobuxus swainii Bleeding Heart Omalanthus populifolius Pinkheart Medicosma cunninghamii Blue Cherry Syzygium oleosum Plum Myrtle Pilidiostigma glabrum Blue Fig Elaeocarpus grandis Poison Corkwood Duboisia myoporoides Blue Lillypilly Syzygium oleosum Prickly Ash Orites excelsa Blue Quandong Elaeocarpus grandis Prickly Tree Fern Cyathea leichhardtiana Blueberry Ash Elaeocarpus reticulatus Purple Cherry Syzygium crebrinerve Blush Walnut Beilschmiedia obtusifolia Red Apple Acmena ingens Bollywood Litsea reticulata Red Ash Alphitonia excelsa Bolwarra Eupomatia laurina Red Bauple Nut Hicksbeachia -

Ba3444 MAMMAL BOOKLET FINAL.Indd

Intot Obliv i The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia Compiled by James Fitzsimons Sarah Legge Barry Traill John Woinarski Into Oblivion? The disappearing native mammals of northern Australia 1 SUMMARY Since European settlement, the deepest loss of Australian biodiversity has been the spate of extinctions of endemic mammals. Historically, these losses occurred mostly in inland and in temperate parts of the country, and largely between 1890 and 1950. A new wave of extinctions is now threatening Australian mammals, this time in northern Australia. Many mammal species are in sharp decline across the north, even in extensive natural areas managed primarily for conservation. The main evidence of this decline comes consistently from two contrasting sources: robust scientifi c monitoring programs and more broad-scale Indigenous knowledge. The main drivers of the mammal decline in northern Australia include inappropriate fi re regimes (too much fi re) and predation by feral cats. Cane Toads are also implicated, particularly to the recent catastrophic decline of the Northern Quoll. Furthermore, some impacts are due to vegetation changes associated with the pastoral industry. Disease could also be a factor, but to date there is little evidence for or against it. Based on current trends, many native mammals will become extinct in northern Australia in the next 10-20 years, and even the largest and most iconic national parks in northern Australia will lose native mammal species. This problem needs to be solved. The fi rst step towards a solution is to recognise the problem, and this publication seeks to alert the Australian community and decision makers to this urgent issue. -

Husbandry Guidelines for Feathertail Gliders

Husbandry Guidelines for (Photo: Luke Hogan, 1996) Feathertail Gliders Acrobates frontalis & Acrobates pygmaeus (Mammalia: Acrobatidae) Date By From Version 2012 Tom Patterson WSI Richmond v 1 Husbandry Manual for the Feathertail Glider DISCLAIMER These husbandry guidelines were produced by the compiler/author at TAFE NSW Western Sydney Institute, Richmond College, N.S.W. Australia as part assessment for completion of Certificate III in Captive Animals, Course number 18913. Since the husbandry guidelines are the result of student project work, care should be taken in the interpretation of information therein. In effect, all care taken but no responsibility is assumed for any loss or damage that may result from the use of these guidelines. Care has been taken to acknowledge the correct ownership of work. Should It is offered to the ASZK Husbandry Manuals Register for the benefit of animal welfare and care. Husbandry guidelines are utility documents and are ‘works in progress’, so enhancements to these guidelines are invited. 2 Annual Cycle of Maintenance Breeding Torpor Exhibit Change Replace Scrub Replace Soil Decrease Pest Collect Scrub Leaf nesting Nest (if applicable) food Control Faecal (1) (2) Litter materials Boxes (Torpor) Samples January February March April May June July August September October November December Note: (1) Northern populations – most likely all Acrobates frontalis, (2) Southern populations – most likely all Acrobates pygmaeus. All maintenance cycle should be used as a guide only. These tasks are noted at a minimum, but should be done as required. Record keeping, weights, observations and environmental enrichment should occur all year round OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS OH&S hazards can include anything that may be seen as a potential risk to you as a keeper or a member of the public. -

Greater Glider Management Plan: South Gippsland. Draft

1 Greater Glider Management Plan: South Gippsland. Draft Greater Glider, Mirboo Regional Park (HVP). Powerful Owls, Mirboo Regional Park (Dickies Hill). 2 INDEX 1. Aim……………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………. 2. Biology………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….. 3. Current Distribution South Gippsland…………………………………………………………….. P.2 4. Greater Glider Populations…………………………………………………....……………………... P.2 4.1. Mirboo Regional Park & Dickies Hill……………………………..…………………………..…. P.2 4.2. Hallston…………………………………………………………………………………………………….…. P.3 4.3. Gunyah rainforest Reserve……………………………………………................................ P.3 5. Threats……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…. P.3 5.1. Habitat Connectivity…………………………………………………..……………………………..… P.4 5.2. Habitat Destruction…………………………………………………………………………………..... P.5 5.3. Predators…………………………………………………………….………………………………….…... P.5 5.4. Climate Change………………………………………………………………………………………….... P.5 5.5. Firewood Collection………………………………………………………………………………….….. P.5 5.6. Timber Production…………………………………………………………………………………..…... P.6 5.7. Other Threats………………………………………………………………….……………………….….. P.6 P.6 6. Management Actions…………………………………………………………………………. P.6 5.1 Current and Future Habitat Restoration …………………………………………………………….… P.7 Hallston……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… P.8 Mirboo RP…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. P.8 5.2 Genetic diversity……………………………………………………………………………………………….... P.10 5.3 Predation………………………………………………………………………………………………………..….. P.13 5.4 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………………………..………. P.14 -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

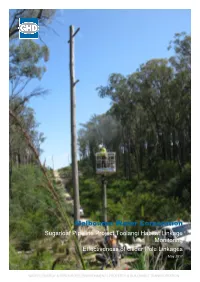

Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring Effectiveness of Glider Pole Linkages May 2017

Melbourne Water Corporation Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring Effectiveness of Glider Pole Linkages May 2017 Acknowledgements The following individuals or groups have assisted in the preparation of this report. However, it is acknowledged that the contents and views expressed within this report are those of GHD Pty Ltd and do not necessarily reflect the views of the parties acknowledged below: The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) for allowing access to records in the VBA database Melbourne Water Corporation staff including Andrea Burns, Paul Evans, Alex Sneskov, Anna Zsoldos, Mark Scida, Warren Tomlinson and Steve McGill for providing assistance, support and advice throughout the project GHD | Report for Melbourne Water Corporation - Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring, 31/29843 | i Abbreviations DELWP Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (formerly DEPI) DEPI Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries (now DELWP) DSE Department of Sustainability and Environment (now DELWP) EPBC Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 EVC Ecological Vegetation Class EWP Elevated Work Platform FFG Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 GHD GHD Pty Ltd ROW Right of Way MW Melbourne Water Corporation Spp. More than one species TSF Toolangi State Forest ii | GHD | Report for Melbourne Water Corporation - Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring, 31/29843 Table of contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. -

Easy Reference Sheet Caring for Gliders

Easy Reference Sheet Caring for Gliders Version: January 2021 There are six species of gliders in Australia, five of which can be found in South-east Queensland. Australian gliders range in size (head and body) from 6.5 - 8cm long (Feathertail Gliders) to 35 - 45cm (Greater Glider). All Australian gliders are nocturnal. Most species have a highly specialised diet, comprising some or all of the following: nectar, pollen, insects, the sap of certain eucalypts and the gum from acacias. However the Greater Glider has a diet similar to the koala, eating only the foliage of certain species of eucalypt. Do I need a Permit to care for gliders? Yes. You will need a REHABILITATION PERMIT to care for gliders. A Rehabilitation Permit can be obtained from a licensed wildlife care group such as Wildcare. Remember all Australian native wildlife is protected in Queensland. You cannot keep them without an appropriate Permit. Do I have to do any training to care for gliders? Yes. Gliders have highly specialised dietary and housing requirements. They often come into care due to loss of habitat, injury or as a result of being orphaned. You must have a good understanding of their biology, be able to recognise signs of illness and injury and be able to provide emergency care to them. In Wildcare, you will need to complete the following training workshops in order to care for gliders:- • Orientation – compulsory for all members • Rescue and First Aid for Wildlife (Basic) – compulsory for all members • Caring for Orphaned Mammals • Gliders Is caring for gliders difficult? Caring for gliders is generally undertaken by experienced possum carers. -

The Lives of Creatures Obscure, Misunderstood, and Wonderful: a Volume in Honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019

Papers in Honour of Ken Aplin edited by Julien Louys, Sue O’Connor and Kristofer M. Helgen Helgen, Kristofer M., Julien Louys, and Sue O’Connor. 2020. The lives of creatures obscure, misunderstood, and wonderful: a volume in honour of Ken Aplin 1958–2019 ..........................149 Armstrong, Kyle N., Ken Aplin, and Masaharu Motokawa. 2020. A new species of extinct False Vampire Bat (Megadermatidae: Macroderma) from the Kimberley Region of Western Australia ........................................................................................................... 161 Cramb, Jonathan, Scott A. Hocknull, and Gilbert J. Price. 2020. Fossil Uromys (Rodentia: Murinae) from central Queensland, with a description of a new Middle Pleistocene species ............................................................................................................. 175 Price, Gilbert J., Jonathan Cramb, Julien Louys, Kenny J. Travouillon, Eleanor M. A. Pease, Yue-xing Feng, Jian-xin Zhao, and Douglas Irvin. 2020. Late Quaternary fossil vertebrates of the Broken River karst area, northern Queensland, Australia ........................ 193 Theden-Ringl, Fenja, Geoffrey S. Hope, Kathleen P. Hislop, and Benedict J. Keaney. 2020. Characterizing environmental change and species’ histories from stratified faunal records in southeastern Australia: a regional review and a case study for the early to middle Holocene ........................................................................................... 207 Brockwell, Sally, and Ken Aplin. 2020. Fauna on -

RIVERDENE TUBESTOCK (50X50x150mm)

RIVERDENE TUBESTOCK (50x50x150mm) KEY : B= Bushtucker G= Grass F = Fodder A = Aquatic T = Timber Production C = Groundcover O = Ornamental (non Native) FN – Fern V – Vine/Climber NAME COMMON NAME COMMENT sandstone areas of the Bulga & Putty districts. Frost & sweetly scented yellow flowers. Grows to 1.5m. Abrophyllum ornans - Native Hydrangea- Tall shrub or drought hardy. Responds well to regular pruning. small tree from 3-6m high. Attractive bushy shrub, best Acacia buxifolia - Box Leaf Wattle - Evergreen shrub to B Acacia decurrens - Green Wattle - A fast growing small in a cool moist position in well drained soils. Ideal with 2m, blue green foliage and massed golden yellow to intermediate spreading tree with attractive dark green ferns. Flowers yellowish white & fragrant. Hardy to light flowers. Best in well drained soils but will withstand short fern-like foliage, & large racemes of yellow ball-flowers in drought only. periods of waterlogging. Full or part shade. Winter. Acacia amblygona - Fan Wattle - Small, spreading shrub Acacia concurrens –Curracabah - Shrub or small tree to Acacia doratoxylon – Currawong - Tall shrub or small ranging from completely prostrate in habit to about 1.5 8m high. Rod like flowers, bright yellow in spring. Very tree up to 8 meters high. Best in well drained soil in full metres high. It has bright yellow flowers over winter and hardy & useful small shade tree. Best in full sun & well sun or dappled shade. Useful forage for farm stock. spring. Likes well drained soils and sunny aspect. drained soil. Frost hardy. Hardy to frost and drought when established. Acacia barringtonensis – Barrington - Decorative shrub Acacia coriacea – Wirewood - Tall shrub 4-5m high. -

Adec Preview Generated PDF File

Records of the Western Australian Museum Supplement No. 57: 341-350 (1999). The Pleistocene mammal fauna of Kelangurr Cave, central montane Irian Jaya, Indonesia Timothy F. Flannery Mammalogy, Australian Museum, 6 College St, Sydney, NSW 2000; email: [email protected] Abstract - Sixteen mammal taxa have been identified on craniodental material from a rich deposit of bones in the first chamber of Kelangurr Cave. The remains of all species except the largest (Maokopia ronaldi and Protemnodon hopei) and the smallest (Miniopterus sp. cf. M. macrocneme) and possibly a single tooth cap of Anisomys imitator, are considered to have been accumulated by Pleistocene Sooty Owls (Tyto tenebricosa). About a dozen bird bones representing species ranging in size from finch to medium-sized honeyeater, and currently unidentifiable, are the only non-mammalian remains from the deposit. Kelangurr Cave is at an elevation of 2,950 m, and presently located in tall upper montane forest. Analysis of the habitat requirements of the fossil mammal fauna indicates that at the time of deposition (25-20,000 BP) the cave was surrounded by alpine tussock grassland and scrub similar to that occurring today at 4,000-4,200 m on Mt Carstensz and Mt Wilhelmina. The age of faunal remains not accumulated by owls is uncertain. There is no evidence of non-analogue mammal communities, and no evidence of extinction among species under 2 kg in weight in the fauna. INTRODUCTION Mission during or before the 1980s. In January 1990 The Kwiyawagi area (Figure 1) is the only part of Or Geoffrey Hope walked in to the West Baliem Irian Jaya that has proved to be rich in Pleistocene valley from Wamena, and found bones to be vertebrate fossils (Flannery 1994). -

On the Evolution of Kangaroos and Their Kin (Family Macropodidae) Using Retrotransposons, Nuclear Genes and Whole Mitochondrial Genomes

ON THE EVOLUTION OF KANGAROOS AND THEIR KIN (FAMILY MACROPODIDAE) USING RETROTRANSPOSONS, NUCLEAR GENES AND WHOLE MITOCHONDRIAL GENOMES William George Dodt B.Sc. (Biochemistry), B.Sc. Hons (Molecular Biology) Principal Supervisor: Dr Matthew J Phillips (EEBS, QUT) Associate Supervisor: Dr Peter Prentis (EEBS, QUT) External Supervisor: Dr Maria Nilsson-Janke (Senckenberg Biodiversity and Research Centre, Frankfurt am Main) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Science and Engineering Faculty Queensland University of Technology 2018 1 Keywords Adaptive radiation, ancestral state reconstruction, Australasia, Bayesian inference, endogenous retrovirus, evolution, hybridization, incomplete lineage sorting, incongruence, introgression, kangaroo, Macropodidae, Macropus, mammal, marsupial, maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony, molecular dating, phylogenetics, retrotransposon, speciation, systematics, transposable element 2 Abstract The family Macropodidae contains the kangaroos, wallaroos, wallabies and several closely related taxa that occupy a wide variety of habitats in Australia, New Guinea and surrounding islands. This group of marsupials is the most species rich family within the marsupial order Diprotodontia. Despite significant investigation from previous studies, much of the evolutionary history of macropodids (including their origin within Diprotodontia) has remained unclear, in part due to an incomplete early fossil record. I have utilized several forms of molecular sequence data to shed