Consequences for Women's Leadership

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA _________________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE ___________________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA TANO Kikao cha Tano – Tarehe 15 Mei, 2014 (Kikao Kilianza Saa tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Anne S. Makinda) Alisoma Dua SPIKA: Waheshimiwa Wabunge, leo ni siku ya Alhamisi, kwa hiyo Kiongozi wa Kambi ya Upinzani hayupo hata ukikaa karibu hapo wewe siyo kiongozi. Kwa hiyo, nitaendelea na wengine kadiri walivyoleta, tunaanza na Mheshimiwa Eugen Mwaiposa. HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati Zifuatazo Ziliwasilishwa Mezani na :- NAIBU WAZIRI WA KATIBA NA SHERIA: Hotuba ya Makadirio ya Matumizi na Mapato ya Fedha ya Wizara ya Katiba na Sheria kwa mwaka wa fedha 2014/2015. NAIBU WAZIRI WA MAMBO YA NDANI YA NCHI: Hotuba ya Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumizi ya Wizara ya Mambo ya Ndani ya Nchi kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. MHE. NYAMBARI C. NYANGWINE (K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA KATIBA, SHERIA NA UTAWALA): Taarifa ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Katiba, Sheria na Utawala Kuhusu Utekelezaji wa Majukumu ya Wizara ya Katiba na Sheria kwa Mwaka wa Fedha wa 2013/2014 na Maoni ya Kamati Kuhusu Makadirio ya Matumizi ya Wizara hiyo kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. 1 Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) MHE. CYNTHIA H. NGOYE (K.n.y. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA ULINZI NA USALAMA): Taarifa ya Kamati ya Kudumu ya Bunge ya Ulinzi na Usalama Kuhusu Utekelezaji wa Majukumu ya Wizara ya Mambo ya Ndani ya Nchi kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2013/2014 na Maoni ya Kamati Kuhusu Makadirio ya Mapato na Matumuzi ya Wizara hiyo kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2014/2015. -

State of Politics in Tanzania

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. TANZANIA RICHARD SHABA July 2007 State of Politics in Tanzania www.kas.de/kenia INTRODUCTION The assessment dwells on the political, eco- nomic and social situation as well on the THERE is a broad consensus that the major actors namely: the ruling and opposi- process of consolidating the transition tion political parties, civil society and the towards participatory political system media, the rise of fundamentalism factor in Tanzania over the past seventeen together with the influence of the external years has achieved remarkable suc- factor in shaping the political process. cess. Whereas once predominantly un- der a single party hegemony, Tanzania THE STATE OF THE ECONOMY AND SO- today is characterized by a plurality of CIAL SERVICES political parties. Though slow; the growth of the independent civil society Ranked 159 th out of 175 countries on the has gained momentum. Human Development Index [HDI] by the United Nations, Tanzania is one of the poor- The country has also witnessed a dramatic est countries in the world. And although transformation of the press. State-owned the economy is growing, it is still very much media outfits that had a virtual monopoly externally oriented with almost 100 percent for decades have now changed their accent of development expenditure externally fi- and become outlets for different voices, not nanced basically by donors. Internal reve- just the ruling party - a major step towards nue collection has not met the objective of promoting democratic practice. This para- collecting at least 18.5 per cent of the GDP digm shift has also helped engender a criti- growth rate. -

Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 114 May - Aug 2016

Tanzanian Affairs Issued by the Britain-Tanzania Society No 114 May - Aug 2016 Magufuli’s “Cleansing” Operation Zanzibar Election Re-run Nyerere Bridge Opens David Brewin: MAGUFULI’S “CLEANSING” OPERATION President Magufuli helps clean the street outside State House in Dec 2015 (photo State House) The seemingly tireless new President Magufuli of Tanzania has started his term of office with a number of spectacular measures most of which are not only proving extremely popular in Tanzania but also attracting interest in other East African countries and beyond. It could be described as a huge ‘cleansing’ operation in which the main features include: a drive to eliminate corruption (in response to widespread demands from the electorate during the November 2015 elections); a cutting out of elements of low priority in the expenditure of government funds; and a better work ethic amongst government employees. The President has changed so many policies and practices since tak- ing office in November 2015 that it is difficult for a small journal like ‘Tanzanian Affairs’ to cover them adequately. He is, of course, operat- ing through, and with the help of ministers, regional commissioners and cover photo: The new Nyerere Bridge in Dar es Salaam (see Transport) Magufuli’s “Cleansing” Operation 3 others, who have been either kept on or brought in as replacements for those removed in various purges of existing personnel. Changes under the new President The following is a list of some of the President’s changes. Some were not carried out by him directly but by subordinates. It is clear however where the inspiration for them came from. -

Bunge Newsletter

BungeNe ewsletter Issue No 008 June 2013 New Budget Cycle Shows Relavance For the first time in recent Tanzania history the engage the government and influence it make sev- Parliament has managed to pass the next financial eral tangible changes in its initial budget proposals. year budget before the onset of that particular year. This has been made possible by the Budget Commit- This has been made possi- tee, another new innovation by Speaker Makinda. ble by adoption of new budget cycle. Under the old cycle, it was not possible to influence According to the new budget cycle, the Parliament the government to make changes in budgetary allo- starts discussing the budget in April as opposed to cations. That was because the main budget was read, old cycle where debate on the new budget started on debated and passed before the sectoral plans. After June and ends in the first or second week of August. the main budget was passed, it was impossible for the MPs and government to make changes in the When the decision was taken to implement the new sectoral budgets since they were supposed to reflect budget cycle and Speaker Anne Makinda announced the main budget which had already been passed. the new modalities many people, including Mem- bers of Parliament, were skeptical. Many stakehold- These and many other changes have been made possi- ers were not so sure that the new cycle would work. ble through the five components implemented under the Parliament five years development plan. “Govern- But Ms Makinda has managed to prove the doubt- ment and Budget Oversight and Accountability is one ers wrong. -

-

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA __________________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE __________________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA MBILI Kikao cha Ishirini na Tatu - Tarehe 14 Julai, 2003 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) DUA Naibu Spika (Mhe. Juma J. Akukweti) Alisoma Dua HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati zifuatazo ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI WA UJENZI: Taarifa ya Mwaka ya Utekelezaji na Hesabu zilizokaguliwa za Bodi ya Usajili wa Wahandisi kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2001/2002 (The Annual Performance Report and Audited Accounts of the Engineers Registration Board for the Financial year 2001/2002). NAIBU WAZIRI WA AFYA: Hotuba ya Bajeti ya Wizara ya Afya kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2003/2004. MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA HUDUMA ZA JAMII: Taarifa ya Kamati ya Huduma za Jamii kuhusu utekelezaji wa Wizara ya Afya katika mwaka uliopita, pamoja na maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Matumizi ya Wizara hiyo kwa mwaka 2003/2004. MASWALI NA MAJIBU Na. 220 Mashamba ya Mifugo MHE. MARIA D. WATONDOHA (k.n.y. MHE. PAUL P. KIMITI) aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa Mkoa wa Rukwa unayo mashamba makubwa ya mifugo kama vile Kalambo, Malonje na Shamba la Uzalishaji wa Mitamba (Nkundi):- (a) Je, Serikali inatoa tamko gani kwa kila shamba ili wananchi wajue hatma ya mashamba hayo? (b) Kwa kuwa uamuzi na jinsi ya kuyatumia mashamba hayo unazidi kuchelewa; je, Serikali haioni kuwa upo uwezekano wa mashamba hayo kuvamiwa na wananchi wenye shida ya ardhi? WAZIRI WA MAJI NA MAENDELEO YA MIFUGO alijibu:- 1 Mheshimiwa Naibu Spika, swali hili linafanana sana na swali Na. 75 lililoulizwa na Mheshimiwa Ponsiano D. Nyami, tulilolijibu tarehe 20 Juni, 2003. -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues United Republic of Tanzania Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA Submitted by: IWGIA Date: June 2012 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Acronyms and abbreviations ACHPR African Commission on Human and Peoples‘ Rights ASDS Agricultural Sector Development Strategy AU African Union AWF African Wildlife Fund CBO Community Based Organization CCM Chama Cha Mapinduzi (Party of the Revolution) CELEP Coalition of European Lobbies for Eastern African Pastoralism CPS Country Partnership Strategy (World Bank) COSOP Country Strategic Opportunities Paper (IFAD) CWIP Core Welfare Indicator Questionnaire DDC District Development Corporation FAO Food and Agricultural Organization FBO Faith Based Organization FGM Female Genital Mutilation FYDP Five Year Development Plan -

TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2013: Who Will Benefit from the Gas Economy, If It Happens?

TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2013: Who will benefit from the gas economy, if it happens? TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2013: Who will benefit from the gas economy, if it happens? TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2013 Who will benefit from the gas economy, if it happens? Supported by: 2 TANZANIA GOVERNANCE REVIEW 2013: Who will benefit from the gas economy, if it happens? ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Policy Forum would like to thank the Foundation for Civil Society for the generous grant that financed Tanzania Governance Review 2013. The review was drafted by Tanzania Development Research Group and edited by Policy Forum. The cartoons were drawn by Adam Lutta (Adamu). Tanzania Governance Reviews for 2006-7, 2008-9, 2010-11, 2012 and 2013 can be downloaded from the Policy Forum website. The views expressed and conclusions drawn on the basis of data and analysis presented in this review do not necessarily reflect those of Policy Forum. TGRs review published and unpublished materials from official sources, civil society and academia, and from the media. Policy Forum has made every effort to verify the accuracy of the information contained in TGR2013, particularly with media sources. However, Policy Forum cannot guarantee the accuracy of all reported claims, statements, and statistics. Whereas any part of this review can be reproduced provided it is duly sourced, Policy Forum cannot accept responsibility for the consequences of its use for other purposes or in other contexts. ISBN:978-9987-708-19-2 For more information and to order copies of the report please contact: Policy Forum P.O. Box 38486 Dar es Salaam Tel +255 22 2780200 Website: www.policyforum.or.tz Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Policy Forum 2015. -

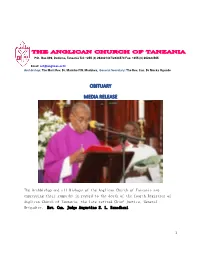

Obituary Media Release

P.O. Box 899, Dodoma, Tanzania Tel: +255 (0) 262321437/2324574 Fax: +255 (0) 262324565 Email: [email protected] Archbishop: The Most Rev. Dr. Maimbo F.W. Mndolwa, General Secretary: The Rev. Can. Dr Mecka Ogunde OBITUARY MEDIA RELEASE The Archbishop and all Bishops of the Anglican Church of Tanzania are expressing their sympathy in regard to the death of the fourth Registrar of Anglican Church of Tanzania, the late retired Chief Justice, General Brigadier, Rev. Can. Judge Augustino S. L. Ramadhani. 1 BIOGRAPHY OF THE LATE GENERAL BRIGADIER, RETIRED CHIEF JUSTICE, JUDGE, REV. CAN. JUDGE AUGUSTINO S. L. RAMADHANI, THE FORTH ACT REGISTRAR 1. BIRTH The late Rev. Can. Judge Augustino Ramadhani was born at Kisima Majongoo, Zanzibar on 28th Dec 1945 (Last days of the second world war). He was the second born in the family of eight children (4 Girls and 4 Boys) of the late Mwalimu Matthew Douglas Ramadhani and Mwalimu Bridget Ann Constance Masoud. 2. CHURCH’S LIFE Augustino was born and raised up in a Christian family despite the facts of the family names that are mixture of both Islam and Christian background. As a Christian he played several roles in the church from the local church to provincial (national) level. At the parish level he was a good chorister, as well as pianist. He is the author of several books and articles. Even after joining military service he continued to serve in the church as secretary for the parish of St Alban in Dar es Salaam. In 2000 he was appointed to be the 4th Provincial Registrar of the Anglican Church of Tanzania (ACT) since the inauguration of the Province in 1970 , the position that he held for seven years until 2007 when he resigned after being appointed as the Chief Justice of Tanzania 25th July 2007 at All Saints Cathedral in the Diocese of Mpwapwa he was honored to be a Lay Canon. -

Hii Ni Nakala Ya Mtandao (Online Document)

Hii ni Nakala ya Mtandao (Online Document) BUNGE LA TANZANIA ___________ MAJADILIANO YA BUNGE _________ MKUTANO WA KUMI NA MBILI Kikao cha Ishirini na Tano - Tarehe 16 Julai, 2003 (Mkutano Ulianza Saa Tatu Asubuhi) D U A Spika (Mhe. Pius Msekwa) Alisoma Dua HATI ZILIZOWASILISHWA MEZANI Hati zifuatazo ziliwasilishwa Mezani na:- NAIBU WAZIRI WA SAYANSI, TEKNOLOJIA NA ELIMU YA JUU: Hotuba ya Waziri wa Sayansi, Teknolojia na Elimu ya Juu kwa Mwaka wa Fedha 2003/2004. MHE. MARGARETH A. MKANGA (k.n.y. MHE. OMAR S. KWAANGW’ - MWENYEKITI WA KAMATI YA HUDUMA ZA JAMII): Taarifa ya Kamati ya Huduma za Jamii kuhusu utekelezaji wa Wizara ya Sayansi, Teknolojia na Elimu ya Juu katika mwaka uliopita, pamoja na maoni ya Kamati kuhusu Makadirio ya Matumizi ya Wizara hiyo kwa Mwaka 2003/2004. MASWALI NA MAJIBU Na. 239 Majimbo ya Uchaguzi MHE. JAMES P. MUSALIKA (k.n.y. MHE. DR. WILLIAM F. SHIJA) aliuliza:- Kwa kuwa baadhi ya Majimbo ya Uchaguzi ni makubwa sana kijiografia na kwa wingi wa watu; je, Serikali itashauriana na Tume ya Uchaguzi ili kuongeza Majimbo ya Uchaguzi katika baadhi ya maeneo nchini katika Uchaguzi wa mwaka 2005? WAZIRI WA NCHI, OFISI YA WAZIRI MKUU (MHE. MUHAMMED SEIF KHATIB) alijibu:- Mheshimiwa Spika, kabla ya kujibu swali la Mheshimiwa Dr. William Shija, Mbunge wa Sengerema, naomba kutoa maelezo yafuatayo:- Mheshimiwa Spika, lilipokuwa linajibiwa swali la Mheshimiwa Ireneus Ngwatura, Mbunge wa Jimbo la Mbinga Magharibi na pia swali la Mheshimiwa Sophia Simba, Mbunge wa Viti Maalum, CCM 1 katika Mikutano ya Saba na Kumi na Moja sawia ya Bungeni, nilieleza kwamba, kwa mujibu wa Ibara ya 75(1) ya Katiba ya Jamhuri ya Muungao wa Tanzania 1977, Jamhuri ya Muungano inaweza kugawanywa katika Majimbo ya Uchaguzi kwa idadi na namna itakavyoamuliwa na Tume ya Taifa ya Uchaguzi baada ya kupata kibali cha Mheshimiwa Rais. -

Tanzanian State

THE PRICE WE PAY TARGETED FOR DISSENT BY THE TANZANIAN STATE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: © Amnesty International (Illustration: Victor Ndula) (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 56/0301/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 METHODOLOGY 8 1. BACKGROUND 9 2. REPRESSION OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION AND INFORMATION 11 2.1 REPRESSIVE MEDIA LAW 11 2.2 FAILURE TO IMPLEMENT EAST AFRICAN COURT OF JUSTICE RULINGS 17 2.3 CURBING ONLINE EXPRESSION, CRIMINALIZATION AND ARBITRARY REGULATION 18 2.3.1 ENFORCEMENT OF THE CYBERCRIMES ACT 20 2.3.2 REGULATING BLOGGING 21 2.3.3 CYBERCAFÉ SURVEILLANCE 22 3. EXCESSIVE INTERFERENCE WITH FACT-CHECKING OFFICIAL STATISTICS 25 4. -

Globalization, National Economy and the Politics of Plunder in Tanzania's

'Conducive environment' for development?: Globalization, national economy and the politics of plunder in Tanzania's mining industry Author: Tundu Lissu Date Written: 1 January 2004 Primary Category: Resource Extraction Document Origin: Lawyers Environmental Action Team Secondary Category: Eastern Region Source URL: http://www.leat.or.tz INTRODUCTION We live in a world transformed in ways that even the most brilliant of the 19th and early 20th century philosophers and political thinkers would find hard to recognize. The power and mobility of finance capital has created the conditions under which rapid scientific and technological change has taken place. This has in turn augmented this power and made it extremely difficult for the state to direct economic and social policy. Capital and foreign exchange controls have everywhere been scrapped; regulations which protected jobs, consumers and the environment; subsidies which benefited the lowest strata of both the urban and rural masses have all gone, as have trade restrictions meant to protect local industries and increase government revenue. These processes have now attained the sanctity of international law through the instrumentality of such institutions as the World Bank Group and WTO and its trade negotiation rounds that have produced GATS, TRIPs, etc. The frontiers of the state have indeed been rolled back. These processes have produced a massive growth in international trade, foreign direct investment flows and unprecedented wealth. Yet they have not led to general prosperity across the world, particularly in poor countries such as Tanzania. On the contrary, general impoverishment comes as an integral part of a global economic order in which an ever-shrinking arrogant officer class , to use the phrase of an eminent British author, lives in affluency.