Post-War Afghanistan: Rebuilding a Ravaged Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

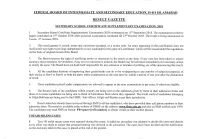

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

Afghan Internationalism and the Question of Afghanistan's Political Legitimacy

This is a repository copy of Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126847/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Leake, E orcid.org/0000-0003-1277-580X (2018) Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. Afghanistan, 1 (1). pp. 68-94. ISSN 2399-357X https://doi.org/10.3366/afg.2018.0006 This article is protected by copyright. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press on behalf of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies in "Afghanistan". Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan’s political legitimacy1 Abstract This article uses Afghan engagement with twentieth-century international politics to reflect on the fluctuating nature of Afghan statehood and citizenship, with a particular focus on Afghanistan’s political ‘revolutions’ in 1973 and 1978. -

A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan

A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF KING AMANULLAH KHAN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iJlajSttr of ^Ijiloioplip IN 3 *Kr HISTORY • I. BY MD. WASEEM RAJA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. R. K. TRIVEDI READER CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDU) 1996 J :^ ... \ . fiCC i^'-'-. DS3004 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY r.u Ko„ „ S External ; 40 0 146 I Internal : 3 4 1 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSTTY M.IGARH—202 002 fU.P.). INDIA 15 October, 1996 This is to certify that the dissertation on "A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan", submitted by Mr. Waseem Raja is the original work of the candidate and is suitable for submission for the award of M.Phil, degree. 1 /• <^:. C^\ VVv K' DR. Rij KUMAR TRIVEDI Supervisor. DEDICATED TO MY DEAREST MOTHER CONTENTS CHAPTERS PAGE NO. Acknowledgement i - iii Introduction iv - viii I THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE 1-11 II HISTORICAL ANTECEDANTS 12 - 27 III AMANULLAH : EARLY DAYS AND FACTORS INFLUENCING HIS PERSONALITY 28-43 IV AMIR AMANULLAH'S ASSUMING OF POWER AND THE THIRD ANGLO-AFGHAN WAR 44-56 V AMIR AMANULLAH'S REFORM MOVEMENT : EVOLUTION AND CAUSES OF ITS FAILURES 57-76 VI THE KHOST REBELLION OF MARCH 1924 77 - 85 VII AMANULLAH'S GRAND TOUR 86 - 98 VIII THE LAST DAYS : REBELLION AND OUSTER OF AMANULLAH 99 - 118 IX GEOPOLITICS AND DIPLCMIATIC TIES OF AFGHANISTAN WITH THE GREAT BRITAIN, RUSSIA AND GERMANY A) Russio-Afghan Relations during Amanullah's Reign 119 - 129 B) Anglo-Afghan Relations during Amir Amanullah's Reign 130 - 143 C) Response to German interest in Afghanistan 144 - 151 AN ASSESSMENT 152 - 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 - 174 APPENDICES 175 - 185 **** ** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The successful completion of a work like this it is often difficult to ignore the valuable suggestions, advice and worthy guidance of teachers and scholars. -

My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Digitized Books Archives & Special Collections 1970 My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Khan, Shah Wali, "My Memoirs" (1970). Digitized Books. 18. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY MEMOIRS ( \ ~ \ BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL COLUMN OF JNDEPENDENCE Afghan Coll. 1970 DS 371 sss A313 His Royal Highness Marshal Sardar Shah Wali Khan Victor of Kabul MY MEMOIRS BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS MARSHAL SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL 1970 PRINTED IN PAKISTAN BY THE PUNJAB EDUCATIONAL PRESS, , LAHORE CONTENTS PART I THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE Pages A Short Biography of His Royal Highness Sardar Shah Wali Khan, Victor of Kabul i-iii 1. My Aim 1 2. Towards the South 7 3. The Grand Assembly 13 4. Preliminary Steps 17 5. Fall of Thal 23 6. Beginning of Peace Negotiations 27 7. The Armistice and its Effects 29 ~ 8. Back to Kabul 33 PART II DELIVERANCE OF THE COUNTRY 9. Deliverance of the Country 35 C\'1 10. Beginning of Unrest in the Country 39 er 11. Homewards 43 12. Arrival of Sardar Shah Mahmud Ghazi 53 Cµ 13. Sipah Salar's Activities 59 s:: ::s 14. -

Afghanistan's Constitution of 1964

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 constituteproject.org Afghanistan's Constitution of 1964 Historical This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 Table of contents Preamble . 3 Title I: The State . 3 Title II: The King . 4 Title III: The Basic Rights and Duties of the People . 8 Title IV: The Shura (Parliament) . 12 Title V: The Loya Jirgah (Great Council) . 19 Title VI: The Government . 20 Title VII: The Judiciary . 22 Title VIII: The Administration . 25 Title IX: State of Emergency . 26 Title X: Amendment . 27 Title XI: Transitional Provision . 28 Afghanistan 1964 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble Preamble • God or other deities In the Name of God, The Almighty and The Just. To re-organize the national life of Afghanistan according to the requirements of the time and on the basis of the realities of national history and culture; To achieve justice and equality; To establish political, economic and social democracy; To organize the functions of the State and its branches to ensure liberty and welfare of the individual and the maintenance of the general order; To achieve a balanced development of all phases of life in Afghanistan; and • Human dignity To form, ultimately, a prosperous and progressive society based on social co-operation and preservation of human dignity; • Source of constitutional authority • Political theorists/figures We, the people of Afghanistan, conscious of the historical changes which have occurred in our life as a nation and as a part of human society, while considering the above-mentioned values to be the right of all human societies, have, under the leadership of His Majesty Mohammed Zahir Shah, the King of Afghanistan and the leader of its national life, framed this Constitution for ourselves and the generations to come. -

A Letter from Afghan Professors

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 12 Issue 1 Article 3 2013 Greetings and Grievances: A Letter from Afghan Professors Laurel Currie Oates Seattle University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Currie Oates, Laurel (2013) "Greetings and Grievances: A Letter from Afghan Professors," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 12 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 61 Greetings and Grievances: A Letter from Afghan Professors Laurel Currie Oates* On that first day, all of us were wary. Although I had taught in Afghanistan on two prior occasions, this was the first time some of my “students” were professors who taught Shariah1 law at the country’s two most conservative universities: the University of Nangarhar, which is in the eastern part of Afghanistan, and the University of Kandahar, which is in the south.2 Wearing traditional clothing and beards, the professors who sat in front of me looked very much like the “insurgents” so often featured on my evening newscasts. I, on the other hand was a woman, albeit an older woman, from the United States.3 * Laurel Currie Oates is a Professor of Law at Seattle University School of Law. -

Interaction Member Activity Report Afghanistan a Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of Interaction Member Agencies in Afghanistan

InterAction Member Activity Report Afghanistan A Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of InterAction Member Agencies in Afghanistan May 2002 Photo by Pieternella Pieterse, courtesy of Concern Worldwide US Produced by Yoko Satomi With the Disaster Response Unit of 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 701, Washington DC 20036 Phone (202) 667-8227 Fax (202) 667-8236 Website: http://www.interaction.org Table of Contents Map of Afghanistan 3 Background Summary 4 Report Summary 6 Organizations by Sector Activity 7 Glossary of Acronyms 9 InterAction Member Activity Report Action Against Hunger USA 11 Air Serv International 13 American Jewish World Service 14 American Refugee Committee 16 AmeriCares 17 America’s Development Foundation 18 Catholic Medical Mission Board 19 Catholic Relief Services 20 Childreach/Plan 21 Christian Children’s Fund 23 Church World Service 25 Concern Worldwide 28 Direct Relief International 30 Doctors Without Borders/ Médecins Sans Frontières 31 HALO Trust 33 International Aid 34 International Rescue Committee 35 Jesuit Refugee Service/USA 38 Lutheran World Relief 39 InterAction Member Activity Report for Afghanistan 1 May 2002 Mercy Corps 40 Northwest Medical Teams 44 Oxfam America 46 Refugees International 48 Relief International 49 Save the Children 52 United Methodist Committee on Relief 54 USA for UNHCR 55 U.S. Fund for UNICEF 57 World Concern 60 World Vision 61 InterAction Member Activity Report for Afghanistan 2 May 2002 Map of Afghanistan Map courtesy of Central Intelligence Agency / World Fact Book InterAction Member Activity Report for Afghanistan 3 May 2002 Background Summary After twenty years of war, including a decade of Soviet occupation and ensuing civil strife, Afghanistan is in shambles. -

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, April 2002*

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, April 2002* April 1 Islamic movement issues fatwa against Afghan administration. (Pakistan-based Afghan Islamic Press news agency / AIP) A new Afghan movement has issued an edict condemning the Afghan interim administration as “apostate” and condemning all its active members to death. The Tahrik-e Afghaniyat-e Islami-e Afghanistan [The Islamic Afghanist Movement of Afghanistan] condemned the leadership for helping "infidels" interfere in Afghanistan and for promoting “non-Islamic values.” The movement said that the leaders of the interim administration had the same status as the leaders of the communist regime, naming in particular Hamed Karzai [the interim leader of Afghanistan under the Bonn Agreement]; Dr Abdollah [the Foreign Minister of the interim administration]; [Mohammad Yunos] Qanuni [the Interior Minister]; [Mohammad Qasem] Fahim [the Minister of Defence]; Gol Agha Sherzai [the Governor of Kandahar]; Hazrat Ali [the commander of military corps of Nangarhar Province]. April 2 Afghan security forces arrest alleged Hezb-e Islami members. (Afghan news agency Bakhtar and Agence France-Press / AFP) Afghan officials said they had uncovered a plot to "sabotage" the interim administration by followers of exiled warlord Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Defence Ministry official Mir Jan said several Hekmatyar loyalists, including a relative of the former finance minister in the Northern Alliance which dominates the interim cabinet, had been arrested in recent days. He said the brother-in-law of former Northern Alliance Finance Minister Sabawon was among the detainees, but he had been released after questioning. Unconfirmed reports said Sabawon, Bashir Khan Baghlani and Juma Khan Hamdard -- all former commanders with Hekmatyar's Hezb-e- Islami [Islamic Party] -- had been arrested, but Mir Jan said this was "not correct". -

Currenttrends in ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY

CurrentTrends IN ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY VOLUME 23 June, 2018 ■ ERBAKAN, KISAKÜREK, AND THE MAINSTREAMING OF EXTREMISM IN TURKEY Svante E. Cornell ■ THE MILLI MUSLIM LEAGUE: THE DOMESTIC POLITICS OF PAKISTAN’S LASHKAR-E-TAIBA C. Christine Fair ■ THE SUNNI RELIGIOUS LEADERSHIP IN IRAQ Nathaniel Rabkin ■ HOW AL-QAEDA WORKS: THE JIHADIST GROUP’S EVOLVING ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN Daveed Gartenstein-Ross & Nathaniel Barr ■ CONFLICTS IN INDONESIAN ISLAM Paul Marshall Hudson Institute Center on Islam, Democracy, and the Future of the Muslim World CurrentTrends IN ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY VOLUME 23 Edited by Hillel Fradkin, Husain Haqqani, and Eric Brown Hudson Institute Center on Islam, Democracy, and the Future of the MuslimWorld ©2018 Hudson Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN: 1940-834X For more information about obtaining additional copies of this or other Hudson Institute publica- tions, please visit Hudson’s website at www.hudson.org/bookstore or call toll free: 1-888-554-1325. ABOUT HUDSON INSTITUTE Hudson Institute is a nonpartisan, independent policy research organization dedicated to innova- tive research and analysis that promotes global security, prosperity, and freedom. Founded in 1961 by strategist Herman Kahn, Hudson Institute challenges conventional thinking and helps man- age strategic transitions to the future through interdisciplinary studies in defense, international re- lations, economics, health care, technology, culture, and law. With offices in Washington and New York, Hud son seeks to guide public policymakers and global leaders in government and business through a vigorous program of publications, conferences, policy briefings, and recommendations. Hudson Institute is a 501(c)(3) organization financed by tax-deductible contributions from private individuals, corporations, foundations, and by government grants. -

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE for the TALIBAN? by Michael Rubin*

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE TALIBAN? By Michael Rubin* Abstract: The September 11, 2001 attacks on New York City and Washington refocused sustained American attention on Afghanistan for the first time since the Soviet invasion ended. The origin and rise of the Taliban became a subject of great interest. The U.S.-backed mujahidin from the era of the Soviet occupation and the Taliban, a movement developed a decade later, were fierce rivals. As such, the “blowback” argument—that Central Intelligence Agency policies of the 1980s are directly responsible for the rise of the Taliban—is inaccurate. It was Pakistan that backed radical Islamists to protect itself from Afghan nationalist claims on Pakistani territory, which Islamabad feared, might pull apart the country. Indeed, for independent Pakistan’s first three decades, nationalist “Pushtunistan” rhetoric from Afghanistan posed a direct threat to Pakistani territorial integrity. As the United States prepared for war subsequent transformation into a safe-haven against Afghanistan, some academics or for the world’s most destructive terror journalists argued that Usama bin Ladin’s al- network is a far more complex story, one Qa’ida group and Afghanistan’s Taliban that begins in the decades prior to the Soviet government were really creations of invasion of Afghanistan. American policy run amok. A pervasive myth exists that the United States was THE CURSE OF AFGHAN DIVERSITY complicit for allegedly training Usama bin Afghanistan’s shifting alliances and Ladin and the Taliban. For example, Jeffrey factions are intertwined with its diversity, Sommers, a professor in Georgia, has though ethnic, linguistic, or tribal variation repeatedly claimed that the Taliban had alone does not entirely explain these turned on “their previous benefactor.” internecine struggles. -

Stabilizing Afghanistan: Proposals for Improving Security, Governance, and Aid/Economic Development

Stabilizing Afghanistan: Proposals for Improving Security, Governance, and Aid/Economic Development Tobias Ellwood, MP Stabilizing Afghanistan: Proposals for Improving Security, Governance, and Aid/Economic Development Tobias Ellwood, MP © 2013 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1101 15th Street NW, 11th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-031-7 Photo credit: ISAF Media April 2013 About this Report The proposals in this report are based on evidence collated from a series of visits to Afghanistan over the last six years. It brings together ideas and concerns expressed by a wide variety of personalities both from Afghanistan and from the international community. Many of the concerns and ideas were presented off the record. The conclusions drawn and the recommendations made are personal and do not reflect the position of the British government. They are meant to encourage further debate about what could be achieved by the Afghan people and the international community in the lead-up to the International Security and Assistance Force’s (ISAF) departure in 2014. About the Author Tobias Ellwood was elected Member of Parliament for Bournemouth East in May 2005. Since then, he has held a range of positions including opposition whip; shadow minister for culture, media and sport; Parliamentary private secretary to Defense Secretary Rt. Hon. -

Zahir Shah's Cabinet, Afghanistan 1963

Zahir Shah’s Cabinet, Afghanistan 1963 MUNUC 33 TABLE OF CONTENTS ______________________________________________________ CHAIR’S LETTER………………………….….………………………………..….3 CRISIS DIRECTOR’S LETTER..…………..………………………………………..5 A BRIEF HISTORY OF AFGHANISTAN………………………………………….6 CURRENT ISSUES…………………………………………..…………………...21 ROSTER……………………………………………………..…………………...31 BIOGRAPHIES……………………………………………..…………………...33 BIBLIOGRAPHY……………..……………………………..…………………...45 2 Zahir Shah’s Cabinet, Afghanistan 1963| MUNUC 33 CHAIR’S LETTER ______________________________________________________ Dear Delegates, Welcome to Afghanistan! My name is Karina Holbrook, and I am the Chair (aka Zahir Shah) of this committee. As chair, I hope to be fair to everyone; more importantly, I want the committee to be fun. The goal of this conference is pedagogy, and I believe that this can best be done through an immersive, interactive experience - in other words, in a continuous crisis committee! I hope that this committee will give all delegates the opportunity to truly shine, both in the frontroom and in the backroom, in the pursuit of a new Afghanistan. On that note, there are a couple of things I would like to address. First, we will not be tolerating any remarks about the Taliban; not only is it completely inappropriate (and will be addressed accordingly), but it is also completely irrelevant to our time - we are, after all, in the 1960s, long before the Taliban even existed. Also, in that vein, I will not be tolerating any Islamophobic, racist, or sexist comments, either “in character” or to a delegate. “Historical accuracy” or “because my character was like that in real life” is not an excuse - after all, at the end of the day we are delegates in 2020, and we can choose to be mindful where our characters did not.