BERKELEY MODEL UNITED NATIONS LXVI Sixty-Sixth Session

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SSC-SUPPL-2018-RESULT.Pdf

FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 1 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 SALIENT FEATURES OF RESULT ALL AREAS G r a d e W i s e D i s t r i b u t i o n Pass Sts. / Grp. / Gender Enrolled Absent Appd. R.L. UFM Fail Pass A1 A B C D E %age G.P.A EX/PRIVATE CANDIDATES Male 6965 132 6833 16 5 3587 3241 97 112 230 1154 1585 56 47.43 1.28 Female 2161 47 2114 12 1 893 1220 73 63 117 625 335 7 57.71 1.78 1 SCIENCE Total : 9126 179 8947 28 6 4480 4461 170 175 347 1779 1920 63 49.86 1.40 Male 1086 39 1047 2 1 794 252 0 2 7 37 159 45 24.07 0.49 Female 1019 22 997 4 3 614 380 1 0 18 127 217 16 38.11 0.91 2 HUMANITIES Total : 2105 61 2044 6 4 1408 632 1 2 25 164 376 61 30.92 0.70 Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 Grand Total : 11231 240 10991 34 10 5888 5093 171 177 372 1943 2296 124 46.34 1.27 FBISE - Computer Section FEDERAL BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION, ISLAMABAD 2 RESULT GAZETTE OF SSC-II SUPPL. EXAMINATION 2018 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE GAZETTE Subjects EHE:I ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - I PST-II PAKISTAN STUDIES - II (HIC) AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I EHE:II ESSENTIAL OF HOME ECONOMICS - II U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I AMD:I ART AND MODEL DRAWING - I (HIC) F-N:I FOOD AND NUTRITION - I U-C:I URDU COMPULSORY - I (HIC) AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II F-N:II FOOD AND NUTRITION - II U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II AMD:II ART AND MODEL DRAWING - II (HIC) G-M:I MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - I U-C:II URDU COMPULSORY - II (HIC) ARB:I ARABIC - I G-M:II MATHEMATICS (GEN.) - II U-S URDU SALEES (IN LIEU OF URDU II) ARB:II ARABIC - II G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I WEL:I WELDING (ARC & GAS) - I BIO:I BIOLOGY - I G-S:I GENERAL SCIENCE - I (HIC) WEL:II WELDING (ARC AND GAS) - II BIO:II BIOLOGY - II G-S:II GENERAL SCIENCE - II WWF:I WOOD WORKING AND FUR. -

RFP Document 11-12-2020.Pdf

Utility Stores Corporation (USC) Tender Document For Supply, Installation, Integration, Testing, Commissioning & Training of Next Generation Point of Sale System as Lot-1 And End-to-end Data Connectivity along with Platform Hosting Services as Lot-2 Of Utility Stores Locations Nationwide on Turnkey Basis Date of Issue: December 11, 2020 (Friday) Date of Submission: December 29, 2020 (Tuesday) Utility Stores Corporation of Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd, Head Office, Plot No. 2039, F-7/G-7 Jinnah Avenue, Blue Area, Islamabad Phone: 051-9245047 www.usc.org.pk Page 1 of 18 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 2. Invitation to Bid ................................................................................................................ 3 3. Instructions to Bidders ...................................................................................................... 4 4. Definitions ......................................................................................................................... 5 5. Interpretations.................................................................................................................... 7 6. Headings & Tiles ............................................................................................................... 7 7. Notice ................................................................................................................................ 7 8. Tender Scope .................................................................................................................... -

Afghan Internationalism and the Question of Afghanistan's Political Legitimacy

This is a repository copy of Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126847/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Leake, E orcid.org/0000-0003-1277-580X (2018) Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan's political legitimacy. Afghanistan, 1 (1). pp. 68-94. ISSN 2399-357X https://doi.org/10.3366/afg.2018.0006 This article is protected by copyright. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Edinburgh University Press on behalf of the American Institute of Afghanistan Studies in "Afghanistan". Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Afghan internationalism and the question of Afghanistan’s political legitimacy1 Abstract This article uses Afghan engagement with twentieth-century international politics to reflect on the fluctuating nature of Afghan statehood and citizenship, with a particular focus on Afghanistan’s political ‘revolutions’ in 1973 and 1978. -

A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan

A POLITICAL BIOGRAPHY OF KING AMANULLAH KHAN DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iJlajSttr of ^Ijiloioplip IN 3 *Kr HISTORY • I. BY MD. WASEEM RAJA UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. R. K. TRIVEDI READER CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDU) 1996 J :^ ... \ . fiCC i^'-'-. DS3004 CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY r.u Ko„ „ S External ; 40 0 146 I Internal : 3 4 1 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSTTY M.IGARH—202 002 fU.P.). INDIA 15 October, 1996 This is to certify that the dissertation on "A Political Biography of King Amanullah Khan", submitted by Mr. Waseem Raja is the original work of the candidate and is suitable for submission for the award of M.Phil, degree. 1 /• <^:. C^\ VVv K' DR. Rij KUMAR TRIVEDI Supervisor. DEDICATED TO MY DEAREST MOTHER CONTENTS CHAPTERS PAGE NO. Acknowledgement i - iii Introduction iv - viii I THE LAND AND THE PEOPLE 1-11 II HISTORICAL ANTECEDANTS 12 - 27 III AMANULLAH : EARLY DAYS AND FACTORS INFLUENCING HIS PERSONALITY 28-43 IV AMIR AMANULLAH'S ASSUMING OF POWER AND THE THIRD ANGLO-AFGHAN WAR 44-56 V AMIR AMANULLAH'S REFORM MOVEMENT : EVOLUTION AND CAUSES OF ITS FAILURES 57-76 VI THE KHOST REBELLION OF MARCH 1924 77 - 85 VII AMANULLAH'S GRAND TOUR 86 - 98 VIII THE LAST DAYS : REBELLION AND OUSTER OF AMANULLAH 99 - 118 IX GEOPOLITICS AND DIPLCMIATIC TIES OF AFGHANISTAN WITH THE GREAT BRITAIN, RUSSIA AND GERMANY A) Russio-Afghan Relations during Amanullah's Reign 119 - 129 B) Anglo-Afghan Relations during Amir Amanullah's Reign 130 - 143 C) Response to German interest in Afghanistan 144 - 151 AN ASSESSMENT 152 - 154 BIBLIOGRAPHY 155 - 174 APPENDICES 175 - 185 **** ** ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The successful completion of a work like this it is often difficult to ignore the valuable suggestions, advice and worthy guidance of teachers and scholars. -

District ATTOCK CRITERIA for RESULT of GRADE 5

District ATTOCK CRITERIA FOR RESULT OF GRADE 5 Criteria ATTOCK Punjab Status Minimum 33% marks in all subjects 88.47% 88.32% PASS Pass + Minimum 33% marks in four subjects and 28 to 32 marks Pass + Pass with 88.88% 89.91% in one subject Grace Marks Pass + Pass with Pass + Pass with grace marks + Minimum 33% marks in four Grace Marks + 96.33% 96.72% subjects and 10 to 27 marks in one subject Promoted to Next Class Candidate scoring minimum 33% marks in all subjects will be considered "Pass" One star (*) on total marks indicates that the candidate has passed with grace marks. Two stars (**) on total marks indicate that the candidate is promoted to next class. PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, RESULT INFORMATION GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Students Students Students Pass % with Pass + Promoted Pass + Gender Registered Appeared Pass 33% marks Students Promoted % Male 10474 10364 8866 85.55 9821 94.76 Public School Female 11053 10988 10172 92.57 10772 98.03 Male 4579 4506 3882 86.15 4313 95.72 Private School Female 3398 3370 3074 91.22 3298 97.86 Male 626 600 426 71.00 533 88.83 Private Candidate Female 384 369 295 79.95 351 95.12 30514 30197 26715 PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Overall Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-138-126 Hadeesa Noor Ul Ain 482 1st 11-153-207 Shams Ul Ain 482 1st 11-138-221 Ia Eman 478 2nd 11-138-290 Manahil Khalid 477 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK Male Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-162-219 Muhammad Hasan Ali 476 1st 11-262-182 Raja Mohammad Bilal 475 2nd 11-135-111 Hammad Hassan 473 3rd PUNJAB EXAMINATION COMMISSION, GRADE 5 EXAMINATION, 2019 DISTRICT: ATTOCK FEMALE Position Holders Roll NO Name Marks Position 11-138-126 Hadeesa Noor Ul Ain 482 1st 11-153-207 Shams Ul Ain 482 1st 11-138-221 Ia Eman 478 2nd 11-138-290 Manahil Khalid 477 3rd j b i i i i Punjab Examination Commission Grade 5 Examination 2019 School wise Results Summary Sr. -

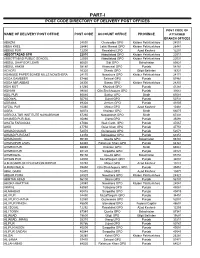

Part-I: Post Code Directory of Delivery Post Offices

PART-I POST CODE DIRECTORY OF DELIVERY POST OFFICES POST CODE OF NAME OF DELIVERY POST OFFICE POST CODE ACCOUNT OFFICE PROVINCE ATTACHED BRANCH OFFICES ABAZAI 24550 Charsadda GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24551 ABBA KHEL 28440 Lakki Marwat GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28441 ABBAS PUR 12200 Rawalakot GPO Azad Kashmir 12201 ABBOTTABAD GPO 22010 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22011 ABBOTTABAD PUBLIC SCHOOL 22030 Abbottabad GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 22031 ABDUL GHAFOOR LEHRI 80820 Sibi GPO Balochistan 80821 ABDUL HAKIM 58180 Khanewal GPO Punjab 58181 ACHORI 16320 Skardu GPO Gilgit Baltistan 16321 ADAMJEE PAPER BOARD MILLS NOWSHERA 24170 Nowshera GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 24171 ADDA GAMBEER 57460 Sahiwal GPO Punjab 57461 ADDA MIR ABBAS 28300 Bannu GPO Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 28301 ADHI KOT 41260 Khushab GPO Punjab 41261 ADHIAN 39060 Qila Sheikhupura GPO Punjab 39061 ADIL PUR 65080 Sukkur GPO Sindh 65081 ADOWAL 50730 Gujrat GPO Punjab 50731 ADRANA 49304 Jhelum GPO Punjab 49305 AFZAL PUR 10360 Mirpur GPO Azad Kashmir 10361 AGRA 66074 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66075 AGRICULTUR INSTITUTE NAWABSHAH 67230 Nawabshah GPO Sindh 67231 AHAMED PUR SIAL 35090 Jhang GPO Punjab 35091 AHATA FAROOQIA 47066 Wah Cantt. GPO Punjab 47067 AHDI 47750 Gujar Khan GPO Punjab 47751 AHMAD NAGAR 52070 Gujranwala GPO Punjab 52071 AHMAD PUR EAST 63350 Bahawalpur GPO Punjab 63351 AHMADOON 96100 Quetta GPO Balochistan 96101 AHMADPUR LAMA 64380 Rahimyar Khan GPO Punjab 64381 AHMED PUR 66040 Khairpur GPO Sindh 66041 AHMED PUR 40120 Sargodha GPO Punjab 40121 AHMEDWAL 95150 Quetta GPO Balochistan 95151 -

My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Digitized Books Archives & Special Collections 1970 My Memoirs Shah Wali Khan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Khan, Shah Wali, "My Memoirs" (1970). Digitized Books. 18. http://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/ascdigitizedbooks/18 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives & Special Collections at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digitized Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MY MEMOIRS ( \ ~ \ BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL COLUMN OF JNDEPENDENCE Afghan Coll. 1970 DS 371 sss A313 His Royal Highness Marshal Sardar Shah Wali Khan Victor of Kabul MY MEMOIRS BY HIS ROYAL HIGHNESS MARSHAL SARDAR SHAH WALi VICTOR OF KABUL KABUL 1970 PRINTED IN PAKISTAN BY THE PUNJAB EDUCATIONAL PRESS, , LAHORE CONTENTS PART I THE WAR OF INDEPENDENCE Pages A Short Biography of His Royal Highness Sardar Shah Wali Khan, Victor of Kabul i-iii 1. My Aim 1 2. Towards the South 7 3. The Grand Assembly 13 4. Preliminary Steps 17 5. Fall of Thal 23 6. Beginning of Peace Negotiations 27 7. The Armistice and its Effects 29 ~ 8. Back to Kabul 33 PART II DELIVERANCE OF THE COUNTRY 9. Deliverance of the Country 35 C\'1 10. Beginning of Unrest in the Country 39 er 11. Homewards 43 12. Arrival of Sardar Shah Mahmud Ghazi 53 Cµ 13. Sipah Salar's Activities 59 s:: ::s 14. -

Afghanistan's Constitution of 1964

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 constituteproject.org Afghanistan's Constitution of 1964 Historical This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 Table of contents Preamble . 3 Title I: The State . 3 Title II: The King . 4 Title III: The Basic Rights and Duties of the People . 8 Title IV: The Shura (Parliament) . 12 Title V: The Loya Jirgah (Great Council) . 19 Title VI: The Government . 20 Title VII: The Judiciary . 22 Title VIII: The Administration . 25 Title IX: State of Emergency . 26 Title X: Amendment . 27 Title XI: Transitional Provision . 28 Afghanistan 1964 Page 2 constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:17 • Motives for writing constitution • Preamble Preamble • God or other deities In the Name of God, The Almighty and The Just. To re-organize the national life of Afghanistan according to the requirements of the time and on the basis of the realities of national history and culture; To achieve justice and equality; To establish political, economic and social democracy; To organize the functions of the State and its branches to ensure liberty and welfare of the individual and the maintenance of the general order; To achieve a balanced development of all phases of life in Afghanistan; and • Human dignity To form, ultimately, a prosperous and progressive society based on social co-operation and preservation of human dignity; • Source of constitutional authority • Political theorists/figures We, the people of Afghanistan, conscious of the historical changes which have occurred in our life as a nation and as a part of human society, while considering the above-mentioned values to be the right of all human societies, have, under the leadership of His Majesty Mohammed Zahir Shah, the King of Afghanistan and the leader of its national life, framed this Constitution for ourselves and the generations to come. -

District ATTOCK Tehsil Group Batch No. Frist Name Last Name Gender

District ATTOCK Tehsil Group Batch No. Frist Name Last Name Gender Teacher Type Cell No. Email EMIS Code School Name ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Aamara Rahim Female Private 0307-0105256 [email protected] other other ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Aasma Zia Female Private 0332-5409991 [email protected] Select School N/A ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Ghafoor Male Public 3215215035 [email protected] 37110050 GHS BOLIAN WAL ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Khamim Male Public 3445659189 [email protected] 37110116 GPS DHAIR ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Malik Male Public 3219951619 NULL 37110147 GES DHOK HAJI AHMED ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Quddos Male Public 3025248671 [email protected] 37110046 GHS SHAKAR DARA ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Razzaq Male Public 3455041578 [email protected] 37110124 GPS FATU CHAK ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Abdul Rehman Male Public 3445036600 [email protected] 37110046 GHS SHAKAR DARA ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Adeela Bibi Female Public 3038044527 [email protected] 37110036 GGHS BOLIAN WAL ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Adeela Bibi Female Public 3165604249 [email protected] 37110381 GGPS MEHR PURA SHARQI ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Adnan Ahmed Male Public 3340101519 [email protected] 37110136 GES HAJI SHAH ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Aftab Ahmed Arshad Male Public 3328551940 [email protected] 37110048 GES SANJWAL ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Ahmed Nawaz Khan Male Public 3465916497 NULL 37110141 GPS DHOK NAWAZ ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 Ajaib Sultana Female Public 3045177288 [email protected] 37110262 GGES MIRZA NO.2 ATTOCK Arts Batch 1 -

Post-War Afghanistan: Rebuilding a Ravaged Nation

POST-WAR AFGHANISTAN: REBUILDING A RAVAGED NATION ISHTIAQ AHMAD Ishtiaq Ahmad is Assistant Professor of International Relations at Eastern Mediterranean University in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The post-11 September US-led war against the sources of Islamic extremism and international terrorism inside Afghanistan has been largely a success. It may be only a matter of time before the remaining Taliban and al-Qaeda pockets of resistance in eastern Afghanistan vanish. The refugees are returning home and the UN-supervised peace package is being implemented successfully. By Afghan standards, these are gigantic achievements in such a short span of time. Yet, given this war-wrecked nation’s horrendous past, the task ahead is gigantic – including the establishment of a truly broad-based government, the creation of a stable internal and external security environment, and the rebuilding of the economic and social fabric of the country, devastated by over 22 years of war. Afghanistan was the world’s worst inheritance from the twentieth century. To make it the best example of the twenty-first century world, the international community under the leadership of the United Nations, has to secure a peaceful, stable and prosperous future for the people of Afghanistan. History was made on 22 December 2001 when a six-month interim administration, with Pashtun leader Hamid Karzai as its chairman, was installed in Kabul. That day, for the first time in decades, Afghanistan saw a peaceful transfer of power and a gathering of former ethnic foes on the same platform. Under the Bonn Agreement of 5 December 2001, the tenure of the interim administration is to end in June 2002, when a Loya Jirgah, a gathering of notables and tribal leaders from all over Afghanistan (around 1,500 people), is to be held in Kabul under the symbolic leadership of former Afghan king Mohammed Zahir Shah, with the purpose of establishing a provisional government for a period of one-and-a-half years. -

To View NSP QAT Schedule

EMIS CODE New QAT Program Sr. No Shift Time SCHOOL NAME Address TEHSIL DISTRICT REGION QAT Day /SCHOOL CODE Date Name 12.30 pm NEW AGE PUBLIC UC Name Dhurnal, UC # 39, Moza FATEH 1 B ATK-FJG-NSP-VIII-3061 ATTOCK North 14 18.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm SCHOOL Dhurnal, Chak / Basti Dhurnal Ada, JANG Tehsil Fateh Jung District Attock 12.30 pm Village Bai, PO Munnoo Nagar, Tehsil HASSANAB 2 B ATK-HDL-NSP-IV-210 Sun Rise High School ATTOCK North 11 14.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm Hassan Abdal, District Attock DAL 12.30 pm Science Secondary Thatti Sado Shah, Po Akhlas, Tehsil PINDI 3 B ATK-PGB-NSP-IV-214 ATTOCK North 16 20.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School Pindi Gheb, District Attock GHEB 12.30 pm Al Aziz Educational Village Gangawali, Teshil Pindi Gheb, PINDI 4 B ATK-PGB-NSP-IV-216 ATTOCK North 17 09.01.19 NSP to 2.30 pm School System District Attock GHEB Basti Haider town(Pindi Gheb), Mouza 12.30 pm PINDI 5 B ATK-PGB-NSP-VII-2477 Hamza Public School Pindi Gheb, UC Name Chakki, UC # 53, ATTOCK North 17 09.01.19 NSP to 2.30 pm GHEB Tehsil Pindi Gheb, District Attock. Mohallah Jibby. Village Qiblabandi, PO 12.30 pm Tameer-e-Seerat Public 6 B ATK-HZO-NSP-IV-211 Kotkay, Via BaraZai, Tehsil Hazro, HAZRO ATTOCK North 12 15.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School District Attock 9.00 am to Stars Public Elementary 7 A ATK-ATK-NSP-IV-207 Dhoke Jawanda, Tehsil & District Attock ATTOCK ATTOCK North 12 15.12.18 NSP 11.00 School 12.30 pm Muslim Scholar Public Dhoke Qureshian, P/O Rangwad, tehsil 8 B ATK-JND-NSP-VI-656 JAND ATTOCK North 15 19.12.18 NSP to 2.30 pm School Jand 12.30 pm Farooqabad -

Open UBL Branches

S.No Branch Code Branch Name Region Province Branch Address 1 0024 Ameen mirpur Azad Kashmir AJK PROPERTY # 21, SECTOR # A-5, SALEEM PLAZA, ALLAMA IQBAL ROAD, MIRPUR 2 0139 Main branch,mirpur Azad Kashmir AJK OPP. POLICE LINES, MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR 3 0157 Dadyal Azad Kashmir AJK Noor Alam Tower<Plot No. 412, Dadyal, District Mirpur, Azad Kashmir 4 0160 Main road chakswari Azad Kashmir AJK KHASRA # 20 BROOTIIAN P.O CHAKSWARI, TEH.& DISTT.MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR. 5 0224 Kotli Azad Kashmir AJK OLD BUS ADDA MAIN BAZAR KOTLI AZAD KASHMIR GROUND FLOOR, ASHRAF CENTRE, MIRPUR CHOWK BHIMBER,TEHSIL BHIMBER, DISTRICT 6 0229 Bhimber Azad Kashmir AJK MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR. 7 0250 Akalgarh azad kashmir Azad Kashmir AJK MAIN BAZAR AKALGARH, TEH.& DISTT. MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR. 8 0348 Mangoabad a k Azad Kashmir AJK MANGOABAD,PO.KANDORE TEHSIL DADYAL, DISTRICT MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR 9 0380 Siakh Azad Kashmir AJK VILL.& PO.SIAKH, TEHSIL DADYAL, DISTRICT MIRPUR,A.K. 10 0467 Sector f/3 branch, mirpur Azad Kashmir AJK PLOT # 515 SECTOR F-3 (PART-1) KOTLI ROAD MIRPUR AZAD KASHMIR 11 0502 Pind kalan Azad Kashmir AJK PIND KALAN, TEH. & DISTT. MIRPUR AZAD KASHMIR. 12 0503 Chattro Azad Kashmir AJK POST OFFICE CHATTRO, TEHSIL DADYAL, DISTRICT MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR. 13 0539 New market ratta a.k. Azad Kashmir AJK VILL.& P.O. RATTA, TEHSIL DADYAL, DISTRICT MIRPUR,A.K. 14 0540 Rakhyal Azad Kashmir AJK POST OFFICE AKALGARH TEH.& DISTT.MIRPUR, AZAD KASHMIR. 15 0567 Ghelay Azad Kashmir AJK REHMAT PLAZA MAIN ROAD JATLAN GHELAY, P.O. , TEH.& DISTT.