Peninsular Bighorn Sheep 2016-17 Annual Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 3.3 Geology Jan 09 02 ER Rev4

3.3 Geology and Soils 3.3.1 Introduction and Summary Table 3.3-1 summarizes the geology and soils impacts for the Proposed Project and alternatives. TABLE 3.3-1 Summary of Geology and Soils Impacts1 Alternative 2: 130 KAFY Proposed Project: On-farm Irrigation Alternative 3: 300 KAFY System 230 KAFY Alternative 4: All Conservation Alternative 1: Improvements All Conservation 300 KAFY Measures No Project Only Measures Fallowing Only LOWER COLORADO RIVER No impacts. Continuation of No impacts. No impacts. No impacts. existing conditions. IID WATER SERVICE AREA AND AAC GS-1: Soil erosion Continuation of A2-GS-1: Soil A3-GS-1: Soil A4-GS-1: Soil from construction existing conditions. erosion from erosion from erosion from of conservation construction of construction of fallowing: Less measures: Less conservation conservation than significant than significant measures: Less measures: Less impact with impact. than significant than significant mitigation. impact. impact. GS-2: Soil erosion Continuation of No impact. A3-GS-2: Soil No impact. from operation of existing conditions. erosion from conservation operation of measures: Less conservation than significant measures: Less impact. than significant impact. GS-3: Reduction Continuation of A2-GS-2: A3-GS-3: No impact. of soil erosion existing conditions. Reduction of soil Reduction of soil from reduction in erosion from erosion from irrigation: reduction in reduction in Beneficial impact. irrigation: irrigation: Beneficial impact. Beneficial impact. GS-4: Ground Continuation of A2-GS-3: Ground A3-GS-4: Ground No impact. acceleration and existing conditions. acceleration and acceleration and shaking: Less than shaking: Less than shaking: Less than significant impact. -

Queen Victoria to Belong to Posterity

AREA POPULATION 3500 Guatay ................, ............. 200 Jamul ................................ 952 Pine Valley ...................... 956 Campo .............................. 1256 Descan, o ... .. .. .... .. ...... ....... 776 Jacumba ............................ 852 Harbison Canyon ............ 1208 ALPINE ECHO Total .............................. 9273 Serving a Growing Area of Homes and Ranches VOL. 5-NO. 34 ----~- 36 ALPINE, CALIFORNIA, THURSDAY, AUGUST 30, 1962 PRICE TEN CENTS QUEEN VICTORIA TO BELONG TO POSTERITY Local Historical Society Works To Preserve Landmark A good crowd of members and guests assembled Sun day, August 26, when the Alpine Historical Society met in the Alpine Woman's Club at 2 p .m. As its first definite project in t he program of locating and preserving authentic historical data of local signifi- cance, the society has started to work on the acquisition of the fa Local Schools Lose mous ·old rock, called Queen Vic- toria which stands in the 2700 10 TeaC hterS block on Victoria Hill. Ten cE>rtificated employees have j After a brief discussion, Presi' left the Alpine Schools this sprina dent Ralph Walker appointed Or·· for greener pastures in other dis~ ville Palmer, president of the Vic tricts with mQ.re attractive sched- toria Hiil Civic Association, as ules. chairman in charge of the rock project. He will work with His Frank J<,seph has accepted a full torical Research committee chair· time administrative position in the man, Philip Hall. Mr. Palmer has Lawndale School, Los Angeles contacted owner of the rock and County. Mr. Joseph will have site, Edward Roper of San Diego, charge o:f a school with an enroH who has expressed willingness to ment of 830 pupils and 23 teach deed it to the society for preserva ers. -

Geology of Hawk Canyon, Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California

GEOLOGY OF HAWK CANYON, ANZA-BORREGO DESERT STATE PARK, CALIFORNIA By Jeffrey D. Pepin Geological Sciences Department California State Polytechnic University Pomona, California 2011 Senior Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science Geology Degree Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................................1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................2 Purpose and Objectives ....................................................................................................2 Regional Geology .............................................................................................................4 Field Site Description .......................................................................................................9 Discussion of Previous Work Done in Hawk Canyon ...................................................11 Observational Data ..........................................................................................................12 Field Techniques ............................................................................................................12 Global Positioning System (GPS) Data and Notes ........................................................14 Orientation Data by Structure ........................................................................................20 Lithology ........................................................................................................................21 -

Ceramic Production and Circulation in the Greater Southwest

MONOGRAPH 44 Ceramic Production and Circulation in the Greater Southwest Source Determination by INAA and Complementary Mineralogical Investigations Edited by Donna M. Glowacki and Hector Neff The Cotsen Institute ofArchaeology University of California, Los Angeles 2002 IO Patayan Ceramic Variability Using Trace Elements and Petrographic Analysis to Study Brown and BuffWares in Southern California john A. Hildebrand, G. Timothy Cross,jerry Schaefer, and Hector Neff N THE LOWER COLORADO RivER and adjacent desert tain a large fraction of granitic inclusions, and when present and upland regions of southern California and in prehistoric pottery, me inclusions may not represent added 0 western Arizona, the late prehistoric Patayan temper but me remnants of incompletely weamered parent produced predominantly undecorated ceramics using a pad rock (Shepard 1964). In the lower Colorado River and Salton dle and anvil technique (Colton 1945; Rogers 1945a; Waters Trough regions, alluvial clays are available with a low iron 1982). Patayan ceramic vessels were important to both mixed content, hence their buff color, and which contain little or horticultural economies along the Colorado and adjacent no intrinsic inclusions. In this case, tempering materials may river systems, and to largely hunting and gathering econo be purposefully added to the alluvial clays. For the historic mies in the adjacent uplands. Patayan ceramic production Kumeyaay/ Kamia, a Yuman-speaking group known to have began at about AD 700 (Schroeder 1961), and continued into occupied both mountain and desert regions west of the low recent times among the Yuman speakers of this region, de er Colorado River (Hicks 1963), the same potters may have scendants of the Patayan (Rogers 1936). -

Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California

Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California Prepared for City of El Centro Community Development Department 1275 Main Street El Centro, CA 92243 Contact: Norma Villicaña Prepared by RECON Environmental, Inc. 3111 Camino del Rio North, Suite 600 San Diego, CA 92108-5726 P 619.308.9333 RECON Number 9781 November 6, 2020 Nathanial Yerka, Project Archaeologist Results of Cultural Resources Survey NATIONAL ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATA BASE INFORMATION Author: Nathanial Yerka Consulting Firm: RECON Environmental, Inc. 3111 Camino del Rio North, Suite 600 San Diego, CA 92108-5726 Report Date: November 6, 2020 Report Title: Results of the Cultural Resources Survey for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project Imperial County, California Prepared for: City of El Centro Community Development Department 1275 Main Street El Centro, CA 92243 Contract Number: RECON Number 9781 USGS Quadrangle Map: El Centro, California, quadrangle, 1979 edition Acreage: 63 acres Keywords: Cultural resources survey, negative prehistoric resources, Date Drain, Dahlia Canal Lateral 1, Imperial Irrigation District, internal canal system This report summarizes the results of the cultural resources field and archival investigation for the Monte Vista Regional Soccer and Wellness Park Project, in the county of Imperial, California. The approximately 80-acre project area is located within the city of El Centro, situated south of West McCabe Road, west of Sperber Road, east and adjacent to a portion of the Dahlia Canal, and approximately 2.5 miles north of the Imperial Valley Irrigation Network’s Main Canal. The assessor’s parcel number for the site is 054-510-001. -

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice

Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego Desert Research Center University of California, Irvine UCI – NATURE and UC Natural Reserve System California State Parks – Colorado Desert District Anza-Borrego Desert State Park & Anza-Borrego Foundation Anza-Borrego Desert State Park Bibliography Compiled and Edited by Jim Dice (revised 1/31/2019) A gaggle of geneticists in Borrego Palm Canyon – 1975. (L-R, Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky, Dr. Steve Bryant, Dr. Richard Lewontin, Dr. Steve Jones, Dr. TimEDITOR’S Prout. Photo NOTE by Dr. John Moore, courtesy of Steve Jones) Editor’s Note The publications cited in this volume specifically mention and/or discuss Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, locations and/or features known to occur within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, biological, geological, paleontological or anthropological specimens collected from localities within the present-day boundaries of Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, or events that have occurred within those same boundaries. This compendium is not now, nor will it ever be complete (barring, of course, the end of the Earth or the Park). Many, many people have helped to corral the references contained herein (see below). Any errors of omission and comission are the fault of the editor – who would be grateful to have such errors and omissions pointed out! [[email protected]] ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As mentioned above, many many people have contributed to building this database of knowledge about Anza-Borrego Desert State Park. A quantum leap was taken somewhere in 2016-17 when Kevin Browne introduced me to Google Scholar – and we were off to the races. Elaine Tulving deserves a special mention for her assistance in dealing with formatting issues, keeping printers working, filing hard copies, ignoring occasional foul language – occasionally falling prey to it herself, and occasionally livening things up with an exclamation of “oh come on now, you just made that word up!” Bob Theriault assisted in many ways and now has a lifetime job, if he wants it, entering these references into Zotero. -

Southern Exposures

Searching for the Pliocene: Southern Exposures Robert E. Reynolds, editor California State University Desert Studies Center The 2012 Desert Research Symposium April 2012 Table of contents Searching for the Pliocene: Field trip guide to the southern exposures Field trip day 1 ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 Robert E. Reynolds, editor Field trip day 2 �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 George T. Jefferson, David Lynch, L. K. Murray, and R. E. Reynolds Basin thickness variations at the junction of the Eastern California Shear Zone and the San Bernardino Mountains, California: how thick could the Pliocene section be? ��������������������������������������������������������������� 31 Victoria Langenheim, Tammy L. Surko, Phillip A. Armstrong, Jonathan C. Matti The morphology and anatomy of a Miocene long-runout landslide, Old Dad Mountain, California: implications for rock avalanche mechanics �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 38 Kim M. Bishop The discovery of the California Blue Mine ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 44 Rick Kennedy Geomorphic evolution of the Morongo Valley, California ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 45 Frank Jordan, Jr. New records -

The Early Utilization and the Distribution of Agave in The

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository UNM Bulletins Scholarly Communication - Departments 1938 The ae rly utilization and the distribution of agave in the American southwest Edward Franklin Castetter Willis Harvey Bell Alvin Russell Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin Recommended Citation Castetter, Edward Franklin; Willis Harvey Bell; and Alvin Russell Grove. "The ae rly utilization and the distribution of agave in the American southwest." University of New Mexico biological series, v. 5, no. 4, University of New Mexico bulletin, whole no. 335, Ethnobiological studies in the American Southwest, 6 5, 4 (1938). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/unm_bulletin/31 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scholarly Communication - Departments at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNM Bulletins by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. hlliig4 The University olNewMexico Bulletin 1 Ethnobiolbgical Studies in the American SouthweSt VI. \The Early Utilization and the Diftribution ofAgave in the American Southweft EDWARD F. CASTETTER, WILLIS H. BELL and ALVIN R. GROVE • .~ ~ r v~r4..f.2.,,",,~- A , ,-' "W'/ I))j j'A1' WJl\( ;JJ;,£~/:(Jcu~~/ HI" I' ~~fi!:~~e . M>rX~;;fre~ UNIVERSITY OF NEW ...//f ':iT' 1938 . Price 50 cents .':.W\~) e.s<:-f1} Qr~: rvJrl The University of New Mexico Vl5 . ,r Bulletin ~('J I 'j"' Ethnobiological Studies In the American Southwest VI. The Early Uttlization and the Distribution ofAgave in the American Southrzvest By EDWARD F. CASTETTER WILLIS H. BELL ALVIN R. GROVE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW MEXICO BULLETIN Whole Number 335 December 1, 1938 Biological Series, Vol. -

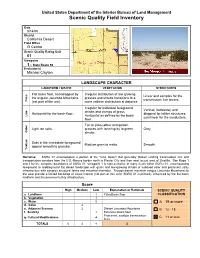

Scenic Quality Field Inventory

United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Scenic Quality Field Inventory Date 8/14/06 District California Desert Field Office El Centro Scenic Quality Rating Unit 01 Viewpoint 1 : State Route 98 Evaluator(s) Michael Clayton LANDSCAPE CHARACTER LANDFORM / WATER VEGETATION STRUCTURES Flat basin floor, backdropped by Irregular distribution of low growing Linear and complex for the the angular Jacumba Mountains grasses and shrubs transitions to a Form transmission line towers. (not part of the unit). more uniform distribution at distance. Irregular for individual foreground Vertical, horizontal, and shrubs and clumps of grass. Horizontal for the basin floor. diagonal for lattice structures, Line Line Horizontal as defined by the basin curvilinear for the conductors. floor. Tan to pale-yellow and golden Light tan soils. grasses with tanish-gray to green Gray. Color shrubs. Soils in the immediate foreground Medium grain to matte. Smooth. appear smooth to granular. Texture Narrative: SQRU 01 encompasses a portion of the Yuha Desert that generally follows existing transmission line and transportation corridors from the U.S.-Mexico border north to Plaster City and then west to just west of Ocotillo. See Maps 1 and 2 for the complete boundaries of SQRU 01. Viewpoint 1 is representative of many views within SQRU 01, encompassing foreground to middleground flat desert landscape with grass and low-growing shrubs of subdued color and prominent utility infrastructure with complex structural forms and industrial character. Though distant mountain ranges (Jacumba Mountains) to the west provide a limited backdrop of visual interest (not part of this unit), SQRU 01 is primarily influenced by the flat basin landform and the prominent utility infrastructure. -

Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring

G ENETIC ORIGINS AND POPULATION STATUS OF DESERT TORTOISES IN A NZA-BORREGO DESERT STATE PARK, CALIFORNIA: INITIAL STEPS TOWARDS POPULATION MONITORING Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D. Environmental Scientist California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 2018. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i Genetic Origins and Population Status of Desert Tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: Initial Steps Towards Population Monitoring Final Report Jeffrey A. Manning, Ph.D., Author / Principle Investigator California Department of Parks and Recreation Colorado Desert District 200 Palm Canyon Drive Borrego Springs, California 92004 November 2018 Manning, J.A. 201 8. Genetic origins and population status of desert tortoises in Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, California: initial steps towards population monitoring. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Colorado Desert District, Borrego Springs, California. 89 pages. i FOREWORD The Desert tortoise (Gopherus sp.) was formally reported to science in 1861, and became the official California state reptile in 1972. Recent studies reveal three species, the Mojave desert tortoise (G. agassizii), Sonoran Desert tortoise (G. morafkai), and Sinaloan desert tortoise (G. evgoodei) (Murphy et al. 2011, Edwards et al. 2016; Figure 1). Range-wide declines in the Mojave desert tortoise population led California to prohibit the collection of this species in 1961. Despite this, it was emergency listed as federally endangered and state listed as threatened in 1989, and subsequently listed as federally threatened in 1990 (Federal Register 55, No 63, 50 CFR Part 17). -

Download Legal Document

Case 4:20-cv-01494-HSG Document 23-1 Filed 04/13/20 Page 1 of 135 1 DROR LADIN* NOOR ZAFAR* 2 JONATHAN HAFETZ** HINA SHAMSI** 3 OMAR C. JADWAT** AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION 4 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004 5 Tel.: (212) 549-2500 Fax: (212) 549-2564 6 [email protected] [email protected] 7 [email protected] [email protected] 8 [email protected] 9 * Admitted pro hac vice **Application for admission pro hac vice forthcoming 10 CECILLIA D. WANG (SBN 187782) 11 AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION 39 Drumm Street 12 San Francisco, CA 94111 Tel.: (415) 343-0770 13 Fax: (415) 395-0950 [email protected] 14 Attorneys for Plaintiffs (Additional counsel listed on following page) 15 16 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 17 SAN FRANCISCO-OAKLAND DIVISION 18 SIERRA CLUB and SOUTHERN BORDER 19 COMMUNITIES COALITION, Case No.: 4:20-cv-01494-HSG 20 Plaintiffs, APPENDIX OF DECLARATIONS IN 21 v. SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY 22 DONALD J. TRUMP, President of the United JUDGMENT States, in his official capacity; MARK T. ESPER, 23 Secretary of Defense, in his official capacity; and CHAD F. WOLF, Acting Secretary of Homeland Judge: Hon. Haywood S. Gilliam, Jr. 24 Security, in his official capacity, Trial Date: None Set Action Filed: February 28, 2020 25 Defendants. 26 27 28 PLAINTIFFS’ APPENDIX OF DECLARATIONS ISO MOTION FOR PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT CASE NO.: 4:20-cv-01494-HSG Case 4:20-cv-01494-HSG Document 23-1 Filed 04/13/20 Page 2 of 135 1 Additional counsel for Plaintiffs: 2 SANJAY NARAYAN (SBN 183227)*** GLORIA D. -

In-Ko-Pah) Wilderness Study Area, Imperial County, California

Mineral Resources of the Jacumba (In-ko-pah) Wilderness Study Area, Imperial County, California U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1711-D Chapter D Mineral Resources of the Jacumba (In-ko-pah) Wilderness Study Area, Imperial County, California By VICTORIA R. TODD, JAMES E. KILBURN, DAVID E. DETRA, ANDREW GRISCOM, and FRED A. KRUSE U.S. Geological Survey EDWARD L McHUGH U.S. Bureau of Mines U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 1711 MINERAL RESOURCES OF WILDERNESS STUDY AREAS: SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA AND CALIFORNIA DESERT CONSERVATION AREA DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1987 For sale by the Books and Open-File Reports Section U.S. Geological Survey Federal Center, Box 25425 Denver, CO 80225 Library of Congress Cataioging-in-Publication Data Mineral resources of the Jacumba (In-ko-pah) Wilderness Study Area, Imperial County, California. U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 1711-D Bibliography: Supt. of Docs. No.: I 19.3:1711-D 1. Mines and mineral resources California Jacumba (In- ko-pah) Wilderness. 2. Jacumba (In-ko-pah) Wilderness (Calif.) I. Todd, Victoria R. (Victoria Roy) II. U.S. Geological Survey. III. Series. QE75.B9 No. 1711-D 557.3 s 87-600129 [TN24.C2] [553'.09794'99] STUDIES RELATED TO WILDERNESS Bureau of Land Management Wilderness Study Areas The Federal Land Policy and Management Act (Public Law 94-579, October 21, 1976) requires the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Bureau of Mines to conduct mineral surveys on certain areas to determine the mineral values, if any, that may be present.