The Shaping of Cultural Knowledge in South African Translation *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

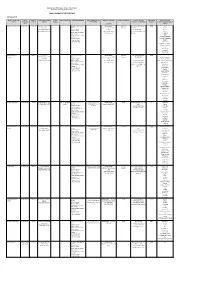

Public Libraries in the Free State

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Idp Review 2020/21

IDP REVIEW 2019/20 IDP REVIEW 2020/21 NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 POLITICAL LEADERSHIP CLLR MJ MOCHELA CLLR NP MOPEDI EXECUTIVE MAYOR SPEAKER WARD 1 WARD 2 WARD 3 WARD 4 CLLR MATROOS CLLR P NDAYI CLLR M MOFOKENG CLLR S NTEO WARD 5 WARD 8 WARD 6 WARD 7 CLLR R KGANTSE CLLR M RAPULENG CLLR M MAGASHULE CLLR M GOBIDOLO WARD 9 WARD 10 WARD 11 WARD 12 CLLR M MBELE CLLR M MOFOKENG CLLR N TLHOBELO CLLR A VREY WARD 13 WARD 14 WARD 15 WARD 16 CLLR H FIELAND CLLR R MEHLO CLLR MOFOKENG CLLR SOCHIVA WARD 17 WARD 18 CLLR M TAJE CLLR M TOYI 2 | P a g e NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATIVE COUNCILLORS NAME & SURNAME PR COUNCILLORS POLITICAL PARTY Motlalepule Mochela PR ANC Neheng Mopedi PR ANC Mvulane Sonto PR ANC Matshepiso Mmusi PR ANC Mabatho Miyen PR ANC Maria Serathi PR ANC Victoria De Beer PR ANC Robert Ferendale PR DA Molaphene Polokoestsile PR DA Alfred Sehume PR DA Shirley Vermaack PR DA Carina Serfontein PR DA Arnold Schoonwinkel PR DA Pieter La Cock PR DA Caroline Tete PR EFF Bakwena Thene PR EFF Sylvia Radebe PR EFF Petrus Van Der Merwe PR VF 3 | P a g e NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TOPIC PAGE NO Political Leadership 2-3 Proportional Representative Councillors 3 Table of Contents 4 List of Tables 5-6 Table of Figure 7 Foreword By Executive Mayor 8 Overview By Municipal Manager 9-11 Executive Summary 12-14 SECTION A Introduction and Current Reality 16 Political governance and administration SECTON B Profile of the municipality 20 SECTION C Spatial -

COVID-19 Laboratory Testing Sites

Care | Dignity | Participation | Truth | Compassion COVID-19 Laboratory testing sites Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing for COVID-19 The information below should give invididuals a clear understanding of the process for risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of patients, visitors, staff, doctors and other healthcare providers at Netcare facilities: • Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of ill individuals Persons who are ill are allowed access to the Netcare facility via the emergency department for risk assessment and screening. Thereafter the person will be clinically assessed by a doctor and laboratory testing for COVID-19 will subsequently be done if indicated. • Laboratory testing of persons sent by external doctors for COVID-19 laboratory testing at a Netcare Group facility Individuals who have been sent to a Netcare Group facility for COVID-19 laboratory testing by a doctor who is not practising at the Netcare Group facility will not be allowed access to the laboratories inside the Netcare facility, unless the person requires medical assistance. This brochure which contains a list of Ampath, Lancet and Pathcare laboratories will be made available to individuals not needing medical assistance, to guide them as to where they can have the testing done. In the case of the person needing medical assistance, they will be directed to the emergency department. No person with COVID-19 risk will be allowed into a Netcare facility for laboratory testing without having consulted a doctor first. • Risk assessment and screening of all persons wanting to enter a Netcare Group facility Visitors, staff, external service providers, doctors and other healthcare providers are being risk assessed at established points outside of Netcare Group hospitals, primary care centres and mental health facilities, prior to them entering the facility. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

Irongate House, Houndsditch EC3 Ruth Siddall Irongate

Urban Geology in London No. 24 Meteorite Impactites in London: Irongate House, Houndsditch EC3 Ruth Siddall Irongate House (below) was designed by architects Fitzroy, Robinson & Partners and completed in 1978. It is a building that is quite easy to ignore. Situated at the Aldgate end of Houndsditch in the City of London, this is a now rather dated, 1970s office block surrounded, and arguably encroached upon by the sparkling glass slabs and cylinders of new modern blocks nicknamed the ‘Gherkin’ and the ‘Cheesegrater’. Walking past, at pavement level, it could indeed be dismissed as the entrance to an underground car park. But look up! Irongate House is a geological gem with a unique and spectacular decorative stone used for cladding the façade. Eric Robinson corresponded with the architects during the building of Irongate House, whilst he was compiling his urban geological walk from the Royal Exchange to Aldgate (Robinson, 1982) and the second volume of the London: Illustrated Geological Walks (Robinson, 1985). Eric discovered that Fitzroy, Robinson & Partners’ stone contractors had chosen a most exotic, unusual and unexpected rock, newly available on the market. This is an orthogneiss from South Africa called the Parys Gneiss. What makes this rock more interesting is that the town of Parys, where the quarries are located, is positioned close to the centre of a major meteorite impact crater, the Vredefort Dome, and the effects of this event, melts associated with the impact called pseudotachylites, cross-cut the gneiss and can be observed here in the City of London. Both to mine and Eric’s knowledge, Parys Gneiss is used here uniquely in the UK, and as such it also made it into Ashurst & Dimes (1998)’s review of building stones. -

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP Name of centre EMIS Category Hosting School Postal address Physical address Telephone Telephone number code number BA-AGI FS035000 PALC IKANYEGENG PO BOX 40 JACOBSDAL 8710 123 SEDITI STRE RATANANG JACOBSDAL 8710 053 5910112 GOLDEN FOUNTAIN FS018001 PALC ORANGE KRAG PRIMARY PO BOX 29 XHARIEP DAM 9922 ORANJEKRAG HYDROPARK LOCAT XHARIEP 9922 051-754 DAM IPOPENG FS029000 PALC BOARAMELO PO BOX 31 JAGERSFONTEIN 9974 965 ITUMELENG L JAGERSFORNTEIN 9974 051 7240304 KGOTHALLETSO FS026000 PALC ZASTRON PUBLIC PO BOX 115 ZASTRON 9950 447 MATLAKENG S MATLAKENG ZASTRPM 9950 051 6731394 LESEDI LA SETJABA FS020000 PALC EDENBURG PO BOX 54 EDENBURG 9908 1044 VELEKO STR HARASEBEI 9908 051 7431394 LETSHA LA FS112000 PALC TSHWARAGANANG PO BOX 56 FAURESMITH 9978 142 IPOPENG FAURESMITH 9978 051 7230197 TSHWARAGANANG MADIKGETLA FS023000 PALC MADIKGETLA PO BOX 85 TROMPSBURG 9913 392 BOYSEN STRE MADIKGETLA TROMPSBU 9913 051 7130300 RG MASIFUNDE FS128000 PALC P/BAG X1007 MASIFUNDE 9750 GOEDEMOED CORRE ALIWAL NORTH 9750 0 MATOPORONG FS024000 PALC ITEMELENG PO BOX 93 REDDERSBURG 9904 821 LESEDI STRE MATOPORONG 9904 051 5530726 MOFULATSHEPE FS021000 PALC MOFULATSHEPE PO BOX 237 SMITHFIELD 9966 474 JOHNS STREE MOFULATHEPE 9966 051 6831140 MPUMALANGA FS018000 PALC PHILIPPOLIS PO BOX 87 PHILIPPOLIS 9970 184 SCHOOL STRE PODING TSE ROLO PHILIPPOLIS 9970 051 7730220 REPHOLOHILE FS019000 PALC WONGALETHU PO BOX 211 BETHULIE 9992 JIM FOUCHE STR LEPHOI BETHULIE 9992 051 7630685 RETSWELELENG FS033000 PALC INOSENG PO BOX 216 PETRUSBURG 9932 NO 2 BOIKETLO BOIKETLO PETRUSBUR 9932 053 5740334 G THUTONG FS115000 PALC LUCKHOFF PO BOX 141 LUCKHOFF 9982 PHIL SAUNDERS A TEISVILLE LUCKHOFF 9982 053 2060115 TSIBOGANG FS030000 PALC LERETLHABETSE PO BOX 13 KOFFIEFONTEIN 9986 831 LEFAFA STRE DITLHAKE 9986 053 2050173 UBUNTU FS035001 PALS SAUNDERSHOOGTE P.O. -

The Clydesdale Coalbrook Colliery Disaster

E-Leader Warsaw 2018 The Clydesdale Coalbrook Colliery Disaster Dennis Schauffer Professor Emeritus, University ofKwaZulu Natal, Durban, South Africa In 1960, just south of Sasolburg, in the province of the Free State, in South Africa, there occurred the greatest coal mining disaster in the history of the continent. Over four hundred miners (435) still lie buried in the mineshafts, forgotten and largely un-commemorated. In what used to be known as Coalbrook and now called Holly Country, which is administered by a Taiwanese Company, lies a rusting piece of mining equipment. If you visit the site in winter when the long grass does not obscure the view, you will find a small brass plaque. It reads: In memory of those 435 miners who lost their lives in the Coalbrook mine disaster on 21/01/1960. “After all these years you are still in our hearts and thoughts” There is a bitter irony in the last sentence as it is difficult to find anyone who can recall even one of the names of any of these miners. This is the only physical tribute ever raised to these men who lost their lives in the mine but mystery surrounds why no organisation was willing to do anything to mark this major event in our history on its 50 th Anniversary in 2010. The relevant Trade Union was not willing to become involved with the commemoration. The reason they gave was that the Union did not exist at the time of the disaster and the Chamber of Mines declined the request by some local concerned residents in Holly Country to hold a commemorative service for the deceased miners with no specific reasons being given for their refusal. -

Free State Province

Agri-Hubs Identified by the Province FREE STATE PROVINCE 27 PRIORITY DISTRICTS PROVINCE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY PROPOSED AGRI-HUB Free State Xhariep Springfontein 17 Districts PROVINCE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY PROPOSED AGRI-HUB Free State Thabo Mofutsanyane Tshiame (Harrismith) Lejweleputswa Wesselsbron Fezile Dabi Parys Mangaung Thaba Nchu 1 SECTION 1: 27 PRIORITY DISTRICTS FREE STATE PROVINCE Xhariep District Municipality Proposed Agri-Hub: Springfontein District Context Demographics The XDM covers the largest area in the FSP, yet has the lowest Xhariep has an estimated population of approximately 146 259 people. population, making it the least densely populated district in the Its population size has grown with a lesser average of 2.21% per province. It borders Motheo District Municipality (Mangaung and annum since 1996, compared to that of province (2.6%). The district Naledi Local Municipalities) and Lejweleputswa District Municipality has a fairly even population distribution with most people (41%) (Tokologo) to the north, Letsotho to the east and the Eastern Cape residing in Kopanong whilst Letsemeng and Mohokare accommodate and Northern Cape to the south and west respectively. The DM only 32% and 27% of the total population, respectively. The majority comprises three LMs: Letsemeng, Kopanong and Mohokare. Total of people living in Xhariep (almost 69%) are young and not many Area: 37 674km². Xhariep District Municipality is a Category C changes have been experienced in the age distribution of the region municipality situated in the southern part of the Free State. It is since 1996. Only 5% of the total population is elderly people. The currently made up of four local municipalities: Letsemeng, Kopanong, gender composition has also shown very little change since 1996, with Mohokare and Naledi, which include 21 towns. -

Provincial Gazette Free State Province

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published byAuthority Uitgegee op Gesag NO. 73 FRIDAY, 01 FEBRUARY 2013 NO. 73 VRYDAG, 01 FEBRUARIE 2013 PROVINCIAL NOTICE PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWING 117 Development facilitation Act, 1995 (Act No. 67 of 1995): 117 Wet opOntwikkelingsfasilitering, 1995 (Wet No. 67 van Administrative District Parys: Amendment of the Vaal 1995): Administratiewe Distrik Parys: Wysiging van River Complex Regional Structure Plan, 1996: dieVaalrivierkompleks Streekstruktuur Plan, 1996: Remainder of the farm Boschbank 12, remainder of Restant van die plaas Boschbank 12, Restant van Portion 2 of the farm Wonderfontein 350, Portions 2, 5, 8 Gedeelte 2 van dieplaas Wonderfontein 350, Gedeeltes and 10 of the farm Rietfontein 251 2 2,5,8 en 10 van dieplaas Rietfontein 251 2 MISCELLANEOUS Applications For Public Road Carrier Permits: Advert 123 2 Advert 124 49 NOTICES KENNISGEWINGS The Conversion of Certain Rights into Leasehold 83 Wet opdie Omskepping van Sekere Regte totHuurpag 86 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE 1PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 01 FEBRUARY 20131 01 FEBRUARIE 2013 2 PROVINCIAL NOTICE PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWING [NO. 117 OF 2012] [NO. 117 VAN 2012] DEVELOPMENT FACILITATION ACT, 1995 (ACT NO. 67 OF 1995): WET OP ONTWIKKELlNGSFASILITERING, 1995 (WET NO. 67 VAN ADMINISTRATIVE DISTRICT PARYS: AMENDMENT OF THE VAAL 1995): ADMINISTRATIEWE DISTRIK PARYS: WYSIGING VAN DIE RIVER COMPLEX REGIONAL STRUCTURE PLAN, 1996: VAALRIVIERKOMPLEKS STREEK-STRUKTUUR PLAN, 1996: REMAINDER OF THE FARM BOSCHBANK 12, REMAINDER OF RESTANT VAN DIE PLAAS BOSCHBANK 12, RESTANT VAN PORTION 2 OF THE FARM WONDERFONTEIN 350, PORTIONS 2, GEDEELTE 2 VAN DIE PLAAS WONDERFONTEIN 350, 5,8 AND 10 OF THE FARM RIETFONTEIN 251 GEDEELTES 2,5,8 EN 10 VAN DIE PLAAS RIETFONTEIN 251 Under the powers vested in me by section 29(3) of the Development Kragtens diebevoegdheid myverleen by artikel 29(3) van die Wet op Facilitation Act, 1995 (Act No. -

Pnads295.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Honourable Premier of the Free State 3 Provincial Map, Free State 4 How to use the HIV-911 directory 6 SEARCH BY DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY DC20 Fezile Dabi 9 DC18 Lejweleputswa 15 DC17 Motheo 21 DC19 Thabo Mofutsanyane 31 DC16 Xhariep 39 Acknowledgements 43 Order form 44 Organisational Update Form - Update your organisational details 45 “This directory of HIV-related services in Free State is partially made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the President’s Emergency Plan.The contents are the responsibility of the Centre for HIV/AIDS Networking (through a Sub-Agreement with Foundation for Professional Development) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government” 1 HOW TO USE THE HIV-911 DIRECTORY WHO IS THE DIRECTORY FOR? This directory is for anyone who is seeking information on where to locate HIV/AIDS services and support in Free State. WHAT INFORMATION DOES THE DIRECTORY CONTAIN? Within the directory you will find information on organisations that provide HIV/AIDS-related services and support in each municipality within Free State. We have provided full contact details, an organisational overview and a listing of services for each organisation. Details on a range of HIV-related services are provided, from government clinics that dispense anti-retro- viral drugs (ARVs) and provide Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT), to faith-based and non-governmental interventions and Community Home-based Care and food parcel support programmes. HOW DO I USE THE DIRECTORY? There are close to 200 organisations working in HIV/AIDS in Free State.