The Clydesdale Coalbrook Colliery Disaster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Assessment for the Proposed Sigma Colliery Ash Backfilling Project

SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR THE PROPOSED SIGMA COLLIERY ASH BACKFILLING PROJECT SASOL MINING (PTY) LIMITED OCTOBER 2013 _________________________________________________ Digby Wells and Associates (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd (Subsidiary of Digby Wells & Associates (Pty) Ltd). Co. Reg. No. 2010/008577/07. Fern Isle, Section 10, 359 Pretoria Ave Randburg Private Bag X10046, Randburg, 2125, South Africa Tel: +27 11 789 9495, Fax: +27 11 789 9498, [email protected], www.digbywells.com ________________________________________________ Directors: A Sing*, AR Wilke, LF Koeslag, PD Tanner (British)*, AJ Reynolds (Chairman) (British)*, J Leaver*, GE Trusler (C.E.O) *Non-Executive _________________________________________________ SOCIAL ASSESSMENT SAS1691 This document has been prepared by Digby Wells Environmental. Report Title: Social Assessment for the Proposed Sigma Colliery Ash Backfilling Project Project Number: SAS1691 Name Responsibility Signature Date Angeline Report writing 15 October 2013 Swanepoel Report writing and Karien Lotter 21 October 2013 review This report is provided solely for the purposes set out in it and may not, in whole or in part, be used for any other purpose without Digby Wells Environmental prior written consent. ii SOCIAL ASSESSMENT SAS1691 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Introduction This document presents the results of a social assessment for the proposed ash backfilling project for Sasol Mining’s (Pty) Ltd (Sasol) Sigma Colliery located near Sasolburg in the Free State Province, South Africa. The following terms of reference (ToR) was developed for the assessment: ■ Update the socio-economic baseline description using 2011 Census statistics; and ■ Identify potential social risks and impacts that may arise as a direct result of the proposed project activities, as well as indirectly as a result of impacts on other aspects of the environment (such as ground and surface water). -

Sasol Beyond South Africa

Sasol beyond South Africa Who is Sasol? Sasol was founded in 1950 as Suid-Afrikaanse Steenkool en Olie (South African Coal and Oil) and was the world’s first coal-to-liquids refinery, now supplying 40% of South Africa’s fuel. The company has technology for the conversion of low-grade coal into synthetic fuels and chemicals. The company is also involved in many other industries, such as olefins and surfactants, polymers, solvents, ammonia, wax and nitrogen (used in fertiliser and explosives), among others. Protestors at the Global Day of Action during the UN’s 17th Conference of the Parties. Photo: groundWork Global activities Sasol is a global company listed on the New York and Johannesburg stock exchanges and has exploration, development, production, marketing and sales operations in thirty-eight countries across the world, including Southern Africa, the rest of Africa, the Americas, the United Kingdom, Europe, the Middle East, Northern Asia, Southeast Asia, the Far East and Australasia. Sasol Petroleum International (SPI) is responsible for Sasol’s oil and gas exploration in countries beyond South Africa, including Gabon, Nigeria, Papua Niue Guinea and Australia, while Sasol Synfuels International (SSI) develops gas-to-liquids (GTL) plants in places such as Latin America, Australasia, Asia-Pacific and the Middle East. 1 Africa Mozambique Mozambique’s current electricity generating capacity is around 2 200 MW, most of it from the Cahora Bassa hydroelectric dam. Most of that power is exported to neighbouring South Africa despite only about 18% of Mozambicans having access to electricity. A $2.1 billion joint venture project between Sasol and Mozambique’s Empresa Nacional Pipelines carrying gas from Mozambique to South Africa de Hidrocarbonetas (ENH) aims http://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/october-2007/pipeline-benefits- to develop a gas resource that mozambique-south-africa has been ‘stranded’ for many years since its discovery in the 1960. -

A Brief History of Wine in South Africa Stefan K

European Review - Fall 2014 (in press) A brief history of wine in South Africa Stefan K. Estreicher Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-1051, USA Vitis vinifera was first planted in South Africa by the Dutchman Jan van Riebeeck in 1655. The first wine farms, in which the French Huguenots participated – were land grants given by another Dutchman, Simon Van der Stel. He also established (for himself) the Constantia estate. The Constantia wine later became one of the most celebrated wines in the world. The decline of the South African wine industry in the late 1800’s was caused by the combination of natural disasters (mildew, phylloxera) and the consequences of wars and political events in Europe. Despite the reorganization imposed by the KWV cooperative, recovery was slow because of the embargo against the Apartheid regime. Since the 1990s, a large number of new wineries – often, small family operations – have been created. South African wines are now available in many markets. Some of these wines can compete with the best in the world. Stefan K. Estreicher received his PhD in Physics from the University of Zürich. He is currently Paul Whitfield Horn Professor in the Physics Department at Texas Tech University. His biography can be found at http://jupiter.phys.ttu.edu/stefanke. One of his hobbies is the history of wine. He published ‘A Brief History of Wine in Spain’ (European Review 21 (2), 209-239, 2013) and ‘Wine, from Neolithic Times to the 21st Century’ (Algora, New York, 2006). The earliest evidence of wine on the African continent comes from Abydos in Southern Egypt. -

The Free State, South Africa

Higher Education in Regional and City Development Higher Education in Regional and City Higher Education in Regional and City Development Development THE FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA The third largest of South Africa’s nine provinces, the Free State suffers from The Free State, unemployment, poverty and low skills. Only one-third of its working age adults are employed. 150 000 unemployed youth are outside of training and education. South Africa Centrally located and landlocked, the Free State lacks obvious regional assets and features a declining economy. Jaana Puukka, Patrick Dubarle, Holly McKiernan, How can the Free State develop a more inclusive labour market and education Jairam Reddy and Philip Wade. system? How can it address the long-term challenges of poverty, inequity and poor health? How can it turn the potential of its universities and FET-colleges into an active asset for regional development? This publication explores a range of helpful policy measures and institutional reforms to mobilise higher education for regional development. It is part of the series of the OECD reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. These reviews help mobilise higher education institutions for economic, social and cultural development of cities and regions. They analyse how the higher education system T impacts upon regional and local development and bring together universities, other he Free State, South Africa higher education institutions and public and private agencies to identify strategic goals and to work towards them. CONTENTS Chapter 1. The Free State in context Chapter 2. Human capital and skills development in the Free State Chapter 3. -

Positive Actions in Turbulent Times

positive actions in turbulent times Our strategy remains unchanged and our value proposition intact. Balancing short-term needs and long-term sustainability, we have continued to renew our business basics, preserving Sasol’s robust fundamentals and delivering a solid performance in deteriorating markets. Our pipeline of growth projects remains strong, even though we have reprioritised capital spending. With our shared values as our guide, we have dealt decisively with disappointments and unprecedented challenges. We are confident that our positive actions will help us navigate the storm and emerge stronger than before. About Sasol sasol annual review and summarised financial information 2009 financial information and summarised review sasol annual Sasol is an energy and chemicals company. We convert coal and gas into liquid fuels, fuel components and chemicals through our proprietary Fischer-Tropsch (FT) processes. We mine coal in South Africa, and produce gas and condensate in Mozambique and oil in Gabon. We have chemical manufacturing and marketing operations in South Africa, Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas. In South Africa, we refine imported crude oil and retail liquid fuels through our network of Sasol convenience centres. We also supply fuels to other distributors in the region and gas to industrial customers in South Africa. Based in South Africa, Sasol has operations in 38 countries and employs some 34 000 people. We continue to pursue international opportunities to commercialise our gas-to-liquids (GTL) and coal-to-liquids (CTL) technology. In partnership with Qatar Petroleum we started up our first international GTL plant, Oryx GTL, in Qatar in 2007. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

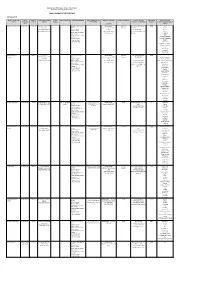

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Idp Review 2020/21

IDP REVIEW 2019/20 IDP REVIEW 2020/21 NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 POLITICAL LEADERSHIP CLLR MJ MOCHELA CLLR NP MOPEDI EXECUTIVE MAYOR SPEAKER WARD 1 WARD 2 WARD 3 WARD 4 CLLR MATROOS CLLR P NDAYI CLLR M MOFOKENG CLLR S NTEO WARD 5 WARD 8 WARD 6 WARD 7 CLLR R KGANTSE CLLR M RAPULENG CLLR M MAGASHULE CLLR M GOBIDOLO WARD 9 WARD 10 WARD 11 WARD 12 CLLR M MBELE CLLR M MOFOKENG CLLR N TLHOBELO CLLR A VREY WARD 13 WARD 14 WARD 15 WARD 16 CLLR H FIELAND CLLR R MEHLO CLLR MOFOKENG CLLR SOCHIVA WARD 17 WARD 18 CLLR M TAJE CLLR M TOYI 2 | P a g e NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 PROPORTIONAL REPRESENTATIVE COUNCILLORS NAME & SURNAME PR COUNCILLORS POLITICAL PARTY Motlalepule Mochela PR ANC Neheng Mopedi PR ANC Mvulane Sonto PR ANC Matshepiso Mmusi PR ANC Mabatho Miyen PR ANC Maria Serathi PR ANC Victoria De Beer PR ANC Robert Ferendale PR DA Molaphene Polokoestsile PR DA Alfred Sehume PR DA Shirley Vermaack PR DA Carina Serfontein PR DA Arnold Schoonwinkel PR DA Pieter La Cock PR DA Caroline Tete PR EFF Bakwena Thene PR EFF Sylvia Radebe PR EFF Petrus Van Der Merwe PR VF 3 | P a g e NGWATHE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY IDP REVIEW 2020/21 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION TOPIC PAGE NO Political Leadership 2-3 Proportional Representative Councillors 3 Table of Contents 4 List of Tables 5-6 Table of Figure 7 Foreword By Executive Mayor 8 Overview By Municipal Manager 9-11 Executive Summary 12-14 SECTION A Introduction and Current Reality 16 Political governance and administration SECTON B Profile of the municipality 20 SECTION C Spatial -

COVID-19 Laboratory Testing Sites

Care | Dignity | Participation | Truth | Compassion COVID-19 Laboratory testing sites Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing for COVID-19 The information below should give invididuals a clear understanding of the process for risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of patients, visitors, staff, doctors and other healthcare providers at Netcare facilities: • Risk assessment, screening and laboratory testing of ill individuals Persons who are ill are allowed access to the Netcare facility via the emergency department for risk assessment and screening. Thereafter the person will be clinically assessed by a doctor and laboratory testing for COVID-19 will subsequently be done if indicated. • Laboratory testing of persons sent by external doctors for COVID-19 laboratory testing at a Netcare Group facility Individuals who have been sent to a Netcare Group facility for COVID-19 laboratory testing by a doctor who is not practising at the Netcare Group facility will not be allowed access to the laboratories inside the Netcare facility, unless the person requires medical assistance. This brochure which contains a list of Ampath, Lancet and Pathcare laboratories will be made available to individuals not needing medical assistance, to guide them as to where they can have the testing done. In the case of the person needing medical assistance, they will be directed to the emergency department. No person with COVID-19 risk will be allowed into a Netcare facility for laboratory testing without having consulted a doctor first. • Risk assessment and screening of all persons wanting to enter a Netcare Group facility Visitors, staff, external service providers, doctors and other healthcare providers are being risk assessed at established points outside of Netcare Group hospitals, primary care centres and mental health facilities, prior to them entering the facility. -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

An Overview of Specified Municipalities Under Repeat Intervention 1

20 October 2020 AN OVERVIEW OF SPECIFIED MUNICIPALITIES UNDER REPEAT INTERVENTION 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides an overview of specified municipalities under repeat intervention in the different provinces constituting the Republic of South Africa. It is common knowledge that the local government sector continues to be in deep crisis with many dysfunctions, which prohibits it from delivering services in a sustainable manner. In every financial year, the Auditor-General reports a series of challenges facing the functionality of local governments. The root causes underlying challenges so cited include, but are not limited to: Lack of commitment at the local administrative and political leadership levels. Lack of decisive leadership in municipal governance and issues of accountability. Poor financial management due to lack of expertise and skills in local government finance. Rising irregular, wasteful, fruitless and unauthorised expenditure. Lack of or weak accountability in local government. Weak oversight of local government performance. Dysfunctional municipal oversight structures, for example, continuing irregularities in the presence of Internal Audit Units and Council Committees. Weak management and control environment. Weaknesses in supply chain management. Poor risk management. Over-reliance on consultants and rising costs of outsourcing municipal functions and mandate. Unstable municipal environment that prohibits service delivery implementation to service the needs of local communities. Corruption in local government. Financial misstatements. Poor revenue and expenditure management, revenue and debt collection, inability to spend allocated infrastructure grants. Use of grant funding to pay for the rising and huge municipal salary and wage bills. 1 NB Some municipalities have a low revenue base. Despite this, they pay their senior management exceedingly high salaries to the extent of lack of affordability. -

Biekie Braai Slaghuis

Biekie Braai SASOLBURG Slaghuis Altyd Vars Vleis Beskikbaar Ons doen Wildsbewerking Biltong - Droëwors - Chilli Bites Braai Pakkies / Braai Lekkernye 21 AUGUSTUS - 27 AUGUSTUS 2018 Tel: (016) 950-7000 Besoek ons by 1 Prinsloo Straat Gratis Verspreiding/Free Distribution: Clydesdale, Deneysville, Kragbron, Sasolburg, Vaalpark. VANDERBIJLPARK. - Stonehaven-on-Vaal’s 20th Spring Don’t forget the amazing well priced country food stalls Beer Festival will be held on Saturday August 25 from 10:00 with hearty helpings to indulge in - and of course, a wide varia- in the morning till midnight. This event promises to be a day ty of beer including a nice selection of craft beers. and night filled with top live entertainment with loads of side Kiddies can look forward to quality complimentary children entertainment. entertainment, water fun in the swimming pool, slip and slide, Bands such as Prime Circle, Gangs of Ballet, CrashCar so kiddies, bring your cossies and towels! There will also be Burn, Wonderboom, Howie Combrink and Pascal & Pearce a big foam pond, giant slide, 8-man rocket and lots more. will grace the audience with their presence by providing the Entrance is R90 for adults, R30 for children under 12 and best music the industry has to offer. children under 5 years are free. Don’t miss out on this fun- This festival also has great competitions lined up like the filled festival! Tickets can be obtained through Computicket Raft Race, a Bikini Competition, a Beer for a Year Competi- and Stonehaven-on-Vaal. tion and Yellow Rubber Duck Race with lots of prizes to be More information is available at (016) 982-2951/2 or in- won. -

Provincial Gazette Free State Province Provinsiale Koerant Provinsie Vrystaat

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag No. 108 FRIDAY, 12 February 2010 No. 108 VRYDAG, 12 Februarie 2010 No. Index Page PROVINCIAL NOTICE 370 PUBLICATION OF THE RESOURCE TARGETING LIST FOR THE NO FEE SCHOOLS 2010 2 2 No. 108 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE, 12 FEBRUARY 2010 PROVINCIAL NOTICE ____________ [No. 370 of 2010] PUBLICATION OF THE RESOURCE TARGETING LIST FOR THE NO FEE SCHOOLS IN 2010 I, PHI Makgoe, Member of the Executive Council responsible for Education in the Province, hereby under section 39(9) read with the National Norms and Standards publish the resource targeting list of public schools for 2010 as set out in the Schedule. PROVINCE: FREE STATE SCHEDULE - DATA ON NO FEE SCHOOLS FOR 2010 1 of 78 PER LEARNER LEARNER EMIS PRIMARY ADDRESS OF QUINTILE NUMBERS ALLOCATION NUMBER NAME OF SCHOOL /SECONDARY SCHOOL TOWN CODE DISTRICT 2010 2010 2010 441811121 AANVOOR PF/S Primary PO BOX 864 HEILBRON 9650 FEZILE DABI Q1 6 855 444306220 ADELINE MEJE P/S Primary PO BOX 701 VILJOENSKROON 9520 FEZILE DABI Q1 1,074 855 441811160 ALICE PF/S Primary PO BOX 251 HEILBRON 9650 FEZILE DABI Q1 14 855 442506122 AMACILIA PF/S Primary PO BOX 676 KROONSTAD 9500 FEZILE DABI Q1 23 855 441610010 ANDERKANT PF/S Primary PO BOX 199 FRANKFORT 9830 FEZILE DABI Q1 34 855 442506284 BANJALAND PF/S Primary PO BOX 1333 KROONSTAD 9500 FEZILE DABI Q1 14 855 442510030 BANKLAAGTE PF/S Primary PO BOX 78 STEYNSRUS 9525 FEZILE DABI Q1 9 855 443011135 BARNARD MOLOKOANE S/S Comp.