(2020) 31: 25–30 Biometry of Two Sympatric

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breeding Biology of Yellow-Browed Antbird Hypocnemis Hypoxantha

Daniel M. Brooks et al. 156 Bull. B.O.C. 2016 136(3) Breeding biology of Yellow-browed Antbird Hypocnemis hypoxantha by Daniel M. Brooks, Pablo Aibar, Pam Bucur, Ron Rossi & Harold F. Greeney Received 17 February 2016 Summary.—We provide novel data concerning the nests, eggs and parental care of Yellow-browed Antbird Hypocnemis hypoxantha based on two nests in eastern Ecuador and Peruvian Amazonia, one of which was video-taped. Both adults participated in incubation, with earliest and latest feeding events at 06.11 h and 17.22 h, respectively. Feeding behaviour is described, with intervals of 1–114 minutes (mean = 38.3 minutes) and tettigoniid cicadas the primary prey. Nestlings frequently produced faecal sacs (interval range = 4–132 minutes, mean = 37.8 minutes) immediately following food delivery, and the sac was always carried from the nest by an adult. Two events involving a parent bird being chased from the nest are described, the first involving a male Fulvous Antshrike Frederickena fulva. Systematics are discussed in light of nest morphology and architecture. Yellow-browed Antbird Hypocnemis hypoxantha is a distinctive Amazonian thamnophilid that comprises two currently recognised subspecies: nominate hypoxantha in western Amazonian lowland and foothill forests from southern Colombia south to central Peru, and H. h. ochraceiventris in south-east Amazonian Brazil (Zimmer & Isler 2003). Generally found below 400 m, the nominate subspecies occasionally ranges as high as 900 m (Zimmer & Isler 2003, Ridgely & Tudor 2009). The species’ reproductive biology is almost completely unknown (Zimmer & Isler 2003). Willis (1988) provided a cursory description of a nest with nestlings from Colombia, but included few details of the nest and no description of the eggs or behaviour. -

Brazil's Eastern Amazonia

The loud and impressive White Bellbird, one of the many highlights on the Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia 2017 tour (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S EASTERN AMAZONIA 8/16 – 26 AUGUST 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL This second edition of Brazil’s Eastern Amazonia was absolutely a phenomenal trip with over five hundred species recorded (514). Some adjustments happily facilitated the logistics (internal flights) a bit and we also could explore some areas around Belem this time, providing some extra good birds to our list. Our time at Amazonia National Park was good and we managed to get most of the important targets, despite the quite low bird activity noticed along the trails when we were there. Carajas National Forest on the other hand was very busy and produced an overwhelming cast of fine birds (and a Giant Armadillo!). Caxias in the end came again as good as it gets, and this time with the novelty of visiting a new site, Campo Maior, a place that reminds the lowlands from Pantanal. On this amazing tour we had the chance to enjoy the special avifauna from two important interfluvium in the Brazilian Amazon, the Madeira – Tapajos and Xingu – Tocantins; and also the specialties from a poorly covered corner in the Northeast region at Maranhão and Piauí states. Check out below the highlights from this successful adventure: Horned Screamer, Masked Duck, Chestnut- headed and Buff-browed Chachalacas, White-crested Guan, Bare-faced Curassow, King Vulture, Black-and- white and Ornate Hawk-Eagles, White and White-browed Hawks, Rufous-sided and Russet-crowned Crakes, Dark-winged Trumpeter (ssp. -

Manaus, Brazil: Amazon Rainforest & River Islands

MANAUS, BRAZIL: AMAZON RAINFOREST & RIVER ISLANDS OCTOBER 4–17, 2019 What simply has to be one of the most beautiful hummingbirds, the Crimson Topaz — Photo: Andrew Whittaker LEADER: ANDREW WHITTAKER LIST COMPILED BY: ANDREW WHITTAKER VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM MANAUS, BRAZIL: AMAZON RAINFOREST & RIVER ISLANDS October 4–17, 2019 By Andrew Whittaker Manaus, without doubt, is one of the world’s major birding crossroads, located smack in the middle of the immense Amazon rainforest, 5,500,000 km 2 (2,123,562 sq mi), home to the richest and most mega diverse biome on our planet! This tour, as usual, offered a perfect opportunity to joyfully immerse ourselves into this fascinating birding and natural history bonanza. I have many fond memories of Manaus, as it was my home for more than 25 years and is always full of exciting surprises. I quickly learned that Amazonia never likes to give up any of its multitude of secrets easily, and, wow, there are so many still to discover! Immense rainforest canopy as far as the eye can see of the famous INPA tower — Photo: Andrew Whittaker Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 Manaus, Brazil, 2019 Amazonia is much more than just the rainforest, as we quickly learned. We also enjoyed exploring the mighty Amazon waterways on our relaxed boat trips, birding avian-rich river islands while being delighted by the exuberant rainforests on either side of the Negro, each with varied and unique species and different microhabitats. Amazonia never fails, and we certainly had our fair share of many delightful, stunning, and unique avian moments together. -

SPLITS, LUMPS and SHUFFLES Splits, Lumps and Shuffles Alexander C

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Alexander C. Lees Crimson-fronted Cardinal Paroaria baeri, an endemic of the Araguaia Valley. Pousada Kuryala, Félix do Araguaia Mato Grosso, Brazil, November 2008 (Bradley Davis / Birding Mato Grosso). This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals—be they entirely new species, splits, lumps or reorganisations—that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment is a bumper one, dominated by the publication of the descriptions of 15 new species (and many splits) for the Amazon in the concluding Special Volume of the Handbook of the Birds of the World (reviewed on pp. 79–80). The last time descriptions of such a large number of new species were published in a single work was in 1871, with Pelzeln’s treatise! Most of these are suboscine passerines—woodcreepers, antbirds and tyrant flycatchers, but even include a new jay. Remaining novelties include papers describing a new tapaculo (who would have guessed), a major rearrangement of Myrmeciza antbirds, more Amazonian splits and oddments involving hermits, grosbeaks and cardinals. Get your lists out! 4 Neotropical Birding 14 Above left: Mexican Hemit Phaethornis mexicanus, Finca El Pacífico, Oaxaca, Mexico, April 2007 (Hadoram Shirihai / Photographic Handbook of the Birds of the World) Above right: Ocellated Woodcreeper Xiphorhynchus ocellatus perplexus, Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserved Zone, Loreto, Peru, October 2008 (Hadoram Shirihai / Photographic Handbook of the Birds of the World) Species status for Mexican endemic to western Mexico and sister to the Hermit remaining populations of P. longirostris. Splits, Lumps and Shuffles is no stranger to A presidential puffbird taxonomic revision of Phaethornis hermits, and The Striolated Puffbird Nystalus striolatus was not readers can look forward to some far-reaching an obvious candidate for a taxonomic overhaul, future developments from Amazonia, but the with two, very morphologically similar subspecies Phaethornis under the spotlight in this issue is recognised: N. -

Brazil's Rio Roosevelt: Birding the River of Doubt 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Brazil's Rio Roosevelt: Birding the River of Doubt 2019 Oct 12, 2019 to Oct 27, 2019 Bret Whitney & Marcelo Barreiros For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Participant Ruth Kuhl captured this wonderful moment from the cabins at Pousada Rio Roosevelt. The 2019 Field Guides Rio Roosevelt & Rio Madeira tour, in its 11th consecutive iteration, took place in October for the first time. It turned out to be a good time to run the tour, although we were just plain lucky dodging rain squalls and thunderstorms a bunch of times during our two weeks. Everyone had been concerned that the widespread burning in the southern Amazon that had been making news headlines for months, and huge areas affected by smoke from the fires, would taint our experience on the tour, but it turned out that rains had started a bit ahead of normal, and the air was totally clear. We gathered in the town of Porto Velho, capital of the state of Rondônia. Our first outing was a late-afternoon riverboat trip on the Rio Madeira, which was a relaxing excursion, and we got to see a few Amazon (Pink) River Dolphins and Tucuxi (Gray River Dolphins) at close range. We then had three full days to bird the west side of the Madeira out of the old Amazonian town of Humaitá. It was a very productive time, as we birded a nice variety of habitats, ranging from vast, open campos and marshes to cerrado (a fire-adapted type of savanna woodland), campinarana woodland (somewhat stunted forest on nutrient-poor soils), and tall rainforest with some bamboo patches. -

West Amazon Boa Vista Tour

(Roraima) Guide: To Be Defined... Day Location (state) Comments 1 Boa Vista Arrival and accommodation. 2 Boa Vista Full Day Birding. 3 Boa Vista – Amajari (210Km) AM Birding. Transfer. PM Birding. 4 Amajari (Serra do Tepequem) Full Day Birding. 5 Amajari – Caracaraí (350Km) AM Birding. Transfer. PM Birding. 6 Caracaraí (Viruá National Park) Full Day Birding. 7 Caracaraí (Viruá National Park) Full Day Birding. 8 Caracaraí (Viruá National Park) Full Day Birding. 9 Caracaraí – Boa Vista (150Km) AM Birding. Transfer. Departure Suggested period: From September to April Boa Vista (A), Amajari (Serra do Tepequem) (B), Caracaraí (C). Day 1: Arrival in Boa Vista where we sleep the night. Day 2: Full Day Birding in BOA VISTA. Area description: The city is on the banks of the rivers Branco and Uraricoera. In the riparian forests we can find several species restricted to this type of vegetation. In addition, other species linked to the dry forests can be found within the city, a few minutes by car. Summary: To start off the tour on full throttle, our first day of birding will have a wide variety of habitats to bird in; forest, open areas (lavrado) and on the margins of Rio Branco river. Some of the birds we will target include White-bellied Piculet (Picumnus spilogaster), Sun Parakeet (Aratinga solstitialis), Pale-tipped Tyrannulet (Inezia caudata), Spectacled Thrush (Turdus nudigenis), Bicolored Wren (Campylorhynchus griseus), Finsch's Euphonia (Euphonia finschi), Black-crested Antshrike (Sakesphorus canadenses), Streak- headed Woodcreeper (Lepidocolaptes souleyetii) Double-striped Thick-knee (Burhinus bistriatus), Yellow Oriole (Icterus nigrogularis), Tropical Mockingbird (Mimus gilvus), Eastern Meadowlark (Sturnella magna), Crested Bobwhite (Colinus cristatus) and many others. -

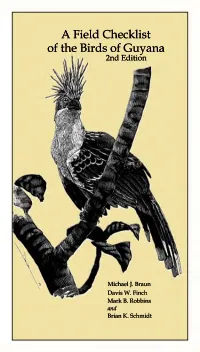

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2Nd Edition

A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition Michael J. Braun Davis W. Finch Mark B. Robbins and Brian K. Schmidt Smithsonian Institution USAID O •^^^^ FROM THE AMERICAN PEOPLE A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana 2nd Edition by Michael J. Braun, Davis W. Finch, Mark B. Robbins, and Brian K. Schmidt Publication 121 of the Biological Diversity of the Guiana Shield Program National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC, USA Produced under the auspices of the Centre for the Study of Biological Diversity University of Guyana Georgetown, Guyana 2007 PREFERRED CITATION: Braun, M. J., D. W. Finch, M. B. Robbins and B. K. Schmidt. 2007. A Field Checklist of the Birds of Guyana, 2nd Ed. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. AUTHORS' ADDRESSES: Michael J. Braun - Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Rd., Suitland, MD, USA 20746 ([email protected]) Davis W. Finch - WINGS, 1643 North Alvemon Way, Suite 105, Tucson, AZ, USA 85712 ([email protected]) Mark B. Robbins - Division of Ornithology, Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA 66045 ([email protected]) Brian K. Schmidt - Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington, DC, USA 20013- 7012 ([email protected]) COVER ILLUSTRATION: Guyana's national bird, the Hoatzin or Canje Pheasant, Opisthocomus hoazin, by Dan Lane. INTRODUCTION This publication presents a comprehensive list of the birds of Guyana with summary information on their habitats, biogeographical affinities, migratory behavior and abundance, in a format suitable for use in the field. It should facilitate field identification, especially when used in conjunction with an illustrated work such as Birds of Venezuela (Hilty 2003). -

Reassessment of the Systematics of the Widespread Neotropical Genus Cercomacra (Aves: Thamnophilidae)

bs_bs_banner Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 170, 546–565. With 7 figures Reassessment of the systematics of the widespread Neotropical genus Cercomacra (Aves: Thamnophilidae) JOSE G. TELLO1,2,3*, MARCOS RAPOSO4, JOHN M. BATES3, GUSTAVO A. BRAVO5†, CARLOS DANIEL CADENA6 and MARCOS MALDONADO-COELHO7 1Department of Biology, Long Island University, Brooklyn, NY 11201, USA 2Department of Ornithology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA 3Center for Integrative Research, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL 60605, USA 4Departamento de Vertebrados, Setor de Ornitologia, Museu Nacional, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 5Museum of Natural Science, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA 70803, USA 6Departamento de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia 7Departamento de Genética e Biologia Evolutiva, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil Received 27 August 2013; revised 3 November 2013; accepted for publication 22 November 2013 A comprehensive molecular phylogeny of the family Thamnophilidae indicated that the widespread neotropical genus Cercomacra Sclater, 1858 is polyphyletic. Two non-sister clades in putative Cercomacra were uncovered: (1) the ‘nigricans’ clade (Cercomacra sensu stricto), formed by manu, brasiliana, cinerascens, melanaria, ferdinandi, carbonaria, and nigricans; and (2) the ‘tyrannina’ clade formed by nigrescens, laeta, parkeri, tyrannina, and serva. Sciaphylax was sister to the ‘tyrannina’ clade and this group was sister to a clade formed by Drymophila and Hypocnemis. This whole major clade then was sister to Cercomacra sensu stricto. Further work is needed to resolve the phylogenetic placement of brasiliana and cinerascens within Cercomacra, and the relationships within the ‘tyrannina’ clade. -

Duets Defend Mates in a Suboscine Passerine, the Warbling Antbird Hypocnemis Cantator

NOT FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Behavioral Ecology doi:10.1093/beheco/ari096 Duets defend mates in a suboscine passerine, the warbling antbird Hypocnemis cantator Nathalie Seddona and Joseph A. Tobiasb aDepartment of Zoology, University of Cambridge,, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK, and bBirdLife International, Wellbrook Court, Girton, Cambridge CB2 ONA, UK Despite the widespread occurrence of avian duets, their adaptive significance is poorly understood. Most research indicates that they function in territory defense, but no study has yet distinguished this hypothesis, which invokes cooperation between the sexes, from mate defense, which invokes conflict. Further, most duetting studies have focused on oscine passerines, yet duets are performed by a number of suboscines. We therefore tested the mate defense hypothesis in the warbling antbird Hypocnemis cantator of Amazonia, a suboscine that produces sex-specific songs and duets. We carried out acoustic analyses of song in conjunction with playback experiments and found support for the hypothesis that females respond to male songs to prevent themselves from being usurped by same-sex rivals. We found that (1) duets were initiated by males, (2) the structure of male but not female song changed during duet formation, (3) swift responses by females resulted in males producing shorter songs comprising fewer notes, (4) solos elicited strong responses from paired birds of either sex, (5) duets elicited weaker responses than same-sex solos from paired birds of either sex, and (6) females responded more strongly to same-sex solos, answering a higher proportion of their partner’s songs and doing so more promptly than after playback of male solos or duets. -

Phenotypic and Niche Evolution in the Antbirds (Aves: Thamnophilidae)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2012 Phenotypic and Niche Evolution in the Antbirds (Aves: Thamnophilidae) Gustavo Adolfo Bravo Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Recommended Citation Bravo, Gustavo Adolfo, "Phenotypic and Niche Evolution in the Antbirds (Aves: Thamnophilidae)" (2012). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4010. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4010 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PHENOTYPIC AND NICHE EVOLUTION IN THE ANTBIRDS (AVES, THAMNOPHILIDAE) A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Biological Sciences by Gustavo Adolfo Bravo B. S. Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia 2002 August 2012 A mis viejos que desde niño me inculcaron el amor por la naturaleza y me enseñaron a seguir mis sueños. And, to the wonderful birds that gave their lives to make this project possible. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I would like to thank my advisors Dr. J. V. Remsen, Jr. and Dr. Robb T. Brumfield. Van and Robb form a terrific team that supported me constantly and generously during my time at Louisiana State University. They were sufficiently wise to let me make my decisions and learn from my successes and my failures. -

Vocal Behaviour of Barred Antshrikes, a Neotropical Duetting Suboscine Bird

J Ornithol (2013) 154:51–61 DOI 10.1007/s10336-012-0867-6 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Vocal behaviour of Barred Antshrikes, a Neotropical duetting suboscine bird Julianne Koloff • Daniel J. Mennill Received: 21 December 2011 / Revised: 3 April 2012 / Accepted: 25 May 2012 / Published online: 23 June 2012 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2012 Abstract Despite the high biodiversity that characterizes of duet responsiveness varied between the sexes; males the tropics, we know little about the behaviour of most responded more quickly to their partner’s song (1.6 s) than tropical birds. Antbirds (Thamnophilidae) are a biodiverse females (2.0 s). This detailed account of the vocalizations family of more than 200 species found throughout Central and vocal behaviour of a population of Barred Antshrikes and South America, yet their ecology and behaviour are creates a foundation for future comparative studies of poorly known. In this study, we provide the first detailed antbirds. Our study highlights similarities and differences description of the vocalizations and vocal behaviour of in the behavioural patterns of tropical birds and contributes Barred Antshrikes (Thamnophilus doliatus), a widespread to our understanding of the function of vocal duets and the Neotropical suboscine passerine. We studied 38 territorial vocal behaviour of antbirds. pairs in a population in Costa Rica from 2008 to 2010, using field recordings and observations to quantify their Keywords Antbird Á Duet Á Song Á Thamnophilidae Á vocalizations and vocal behaviour. Males and females Vocal behaviour produced similar songs consisting of rapidly repeated chuckling notes. Several aspects of their songs distinguish Zusammenfassung the sexes: male songs were longer in duration, contained more syllables, and were lower in pitch. -

Signal Design and Perception in Hypocnemis Antbirds: Evidence for Convergent Evolution Via Social Selection

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00795.x SIGNAL DESIGN AND PERCEPTION IN HYPOCNEMIS ANTBIRDS: EVIDENCE FOR CONVERGENT EVOLUTION VIA SOCIAL SELECTION Joseph A. Tobias1,2 and Nathalie Seddon1,3 1Edward Grey Institute, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, OX1 3PS, United Kingdom 2E-mail: [email protected] 3E-mail: [email protected] Received March 29, 2009 Accepted July 15, 2009 Natural selection is known to produce convergent phenotypes through mimicry or ecological adaptation. It has also been proposed that social selection—i.e., selection exerted by social competition—may drive convergent evolution in signals mediating interspe- cific communication, yet this idea remains controversial. Here, we use color spectrophotometry, acoustic analyses, and playback experiments to assess the hypothesis of adaptive signal convergence in two competing nonsister taxa, Hypocnemis peruviana and H. subflava (Aves: Thamnophilidae). We show that the structure of territorial songs in males overlaps in sympatry, with some evi- dence of convergent character displacement. Conversely, nonterritorial vocal and visual signals in males are strikingly diagnostic, in line with 6.8% divergence in mtDNA sequences. The same pattern of variation applies to females. Finally, we show that songs in both sexes elicit strong territorial responses within and between species, whereas songs of a third, allopatric and more closely related species (H. striata) are structurally divergent and elicit weaker responses. Taken together, our results provide compelling evidence that social selection can act across species boundaries to drive convergent or parallel evolution in taxa competing for space and resources. KEY WORDS: Character displacement, convergent evolution, interspecific competition, signal evolution, species recognition, suboscine birds, territorial signals.