Week 21: Social Policy and the Founding of Ming Section 1: a Comparison Between the Ming and the 20Th Century China 1. a Histori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China

Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China by Gang Pan A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Gang Pan 2015 Prodigals in Love: Narrating Gay Identity and Collectivity on the Early Internet in China Gang Pan Doctor of Philosophy Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 2015 Abstract This dissertation concerns itself with the eruption of a large number of gay narratives on the Chinese internet in its first decade. There are two central arguments. First, the composing and sharing of narratives online played the role of a social movement that led to the formation of gay identity and collectivity in a society where open challenges to the authorities were minimal. Four factors, 1) the primacy of the internet, 2) the vernacular as an avenue of creativity and interpretation, 3) the transitional experience of the generation of the internet, and 4) the evolution of gay narratives, catalyzed by the internet, enhanced, amplified, and interacted with each other in a highly complicated and accelerated dynamic, engendered a virtual gay social movement. Second, many online gay narratives fall into what I term “prodigal romance,” which depicts gay love as parent-obligated sons in love with each other, weaving in violent conflicts between desire and duty in its indigenous context. The prodigal part of this model invokes the archetype of the Chinese prodigal, who can only return home having excelled and with the triumph of his journey. -

By Cao Cunxin

Introduction On a cold December night in Quedlinburg, Germany, in 1589, thirty-two women were burnt at the stake, accused of possessing mysterious powers that enabled them to perform evil deeds. Thousands of people were similarly persecuted between the fifteenth and the seventeenth centuries.1 However, this event was not unique, as fifty years earlier on a rainy night in August, 1549, ninety-seven maritime merchants were beheaded on the coast of Zhejiang 浙江 province for violation of the Ming maritime prohibition. In addition, 117,000 coastal people were immediately ban- ished from their homes to prevent them from going to sea. Thousands of Chinese and foreign merchants lost their lives in the subsequent military campaigns in support of the maritime interdiction. 2 If historians were asked to list the early modern phenomena that have most „disturbed‟ their academic rationale, the two centuries-long witch-hunt in early modern Europe (1500–1700) and the 200 year term of the maritime prohibition, or “hajin 海禁” (1372–1568), during the Ming dynasty (1368––1644) would probably be near the top of the list. For the past few centuries, scholars have debated vigorously the two phenomena and tried to iden- tify the factors that led to their formation, maintenance and eventual change. While the study of the witch-hunt has generated a degree of consensus, there are still many questions surrounding the Ming maritime prohibition. The maritime prohibition policy, introduced in 1371 by the newly enthroned Ming founder, the Hongwu Emperor 洪武 (r. 1368–1398), was institutionalised to maintain systematic control over foreign contact and foreign trade relations. -

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SPRING SEMESTER 2017 Data As of June 7, 2017

THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SPRING SEMESTER 2017 Data as of June 7, 2017 Australia Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Caudle, Emily May Canberra 2609 Bachelor of Science in Industrial and Systems Eng Cum Laude Williams, Stephanie Kate Trevallyn 7250 Bachelor of Arts THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Enrollment Services - Analysis and Reporting June 7, 2017 Page 1 of 95 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SPRING SEMESTER 2017 Data as of June 7, 2017 Bangladesh Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Monika, Sadia Khandaker Dhaka Master of Science Ahmed, Tahmina Dhaka 1000 Master of Accounting Ali, Syed Ashraf Dhaka 1207 Doctor of Philosophy Riyad, M Faisal Dhaka 1219 Master of Science THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Enrollment Services - Analysis and Reporting June 7, 2017 Page 2 of 95 THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Degrees Conferred SPRING SEMESTER 2017 Data as of June 7, 2017 Brazil Sorted by Zip Code, City and Last Name Degree Student Name (Last, First, Middle) City State Zip Degree Honor Palermo dos Santos, Raphael Jundiai SP 13212 Master of Arts Grasso, Marco Antonio Itu, Sao Paulo 13308 Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering Kretli Castro, Ayrton Conrado Vitoria, Es 29057 Master of Business Administration Sprintzin, Leonardo Curitiba 80240 Bachelor of Arts Magna Cum Laude Moraes, Eduardo Quintana Porto Alegre 90470 Master of Business Administration Pereira da Cruz Benetti, Lucia Porto -

Proclamation of the Hongwu Emperor Zhongwen

Proclamation Of The Hongwu Emperor Zhongwen Comether Warren ravaged some modifiers after chaffiest Phineas chouse upstate. Utilizable Erick usually mischarge some gewgaw or slobber deceitfully. Cleistogamous Dalton juts his subsequence licenses hitherto. China their palaces except one example, emperor of the proclamation banning trade was based on ruling elite had Further reproduction or distribution is prohibited without prior permission in writing from the publishers. This offer was declined, but he was granted honorific Ming titles for his gesture. Chinese Empire becoming a theocracy. The one great advantage of the lesser functionaries over officials was that officials were periodically rotated and assigned to different regional posts and had to rely on the good service and cooperation of the local lesser functionaries. Under his successor, however, they began regaining their old influence. The new agricultural policies did pay off and slowly but surely agricultural rose and the economy was revived. As government officials, they also enjoyed certain privileges, such as being excused from taxes and military service. Zhongguo zhenxi falü dianji xubian. At the provincial level, the Yuan central government structure was copied by the Ming; the bureaucracy contained three provincial commissions: one civil, one military, and one for surveillance. After his death, his physicians were penalized. Chinese power and establish a dynasty that saw unprecedented economic growth and a flourishing of the arts. However, total conformity to a single mode of thought was never a reality in the intellectual sphere of society. What a difficult situation this is! Thus, construction on the Great Wall would continue. Restore civil service exams Confucian teachings. -

The Ming Dynasty Its Origins and Evolving Institutions

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES MICHIGAN PAPERS IN CHINESE STUDIES NO. 34 THE MING DYNASTY ITS ORIGINS AND EVOLVING INSTITUTIONS by Charles O. Hucker Ann Arbor Center for Chinese Studies The University of Michigan 1978 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1978 by Charles O. Hucker Published by Center for Chinese Studies The University of Michigan Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Hucker, Charles O. The Ming dynasty, its origins and evolving institutions. (Michigan papers in Chinese studies; no. 34) Includes bibliographical references. 1. China—History—Ming dynasty, 1368-1644. I. Title. II. Series. DS753.H829 951f.O26 78-17354 ISBN 0-89264-034-0 Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89264-034-8 (hardcover) ISBN 978-0-472-03812-1 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12758-0 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90153-1 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ CONTENTS Preface vii I. Introduction 1 n. The Transition from Yuan to Ming 3 Deterioration of Mongol Control 3 Rebellions of the 1350s and 1360s 8 The Rise of Chu Yuan-chang 15 Expulsion of the Mongols 23 III. Organizing the New Dynasty 26 Continuing Military Operations 28 Creation of the Ming Government 33 T!ai-tsufs Administrative Policies 44 Personnel 45 Domestic Administration 54 Foreign Relations and Defense 62 The Quality of Tfai-tsufs Reign 66 IV. -

Ming Fever: the Past in the Present in the People's Republic of China at 60

Ming Fever: The Past in the Present in the People’s Republic of China at 60 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Szonyi, Michael. 2011. Ming fever: The past in the present in the People’s Republic of China at 60. In The People’s Republic of China at 60: An international assessment, ed. William Kirby, 375-387. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Asia Center. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33907949 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP Ming Fever: The Past in the Present in the People’s Republic of China at Sixty Michael Szonyi1 In summer 2007, while gathering materials in rural south China, I was struck by how often history came up in conversation with the villagers I was interviewing. Evening interviews had to be scheduled around the nightly television broadcast of a miniseries about the founding emperor of the Ming, the Hongwu emperor Zhu Yuanzhang. Next morning, everybody was talking about the previous night’s episode. Browsing the main Xinhua bookstore in Beijing on my way home, I was also struck that the biggest bestseller, the book with the most prominent display, was not a guide to succeeding in business or preparing for the TOEFL, but a work of history. -

Chinese Primacy in East Asian History: Deconstructing the Tribute System in China’S Early Ming Dynasty

The London School of Economics and Political Science Chinese Primacy in East Asian History: Deconstructing the Tribute System in China’s Early Ming Dynasty Feng ZHANG A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, April 2009 1 UMI Number: U615686 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615686 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TrttSCS f <tu>3 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. -

Downloaded010006 from Brill.Com09/25/2021 09:53:09AM Via Free Access Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Course of History 89

Journal of Chinese Humanities � (�0�5) 88-��9 brill.com/joch Northern and Southern Dynasties and the Course of History Since Middle Antiquity Li Zhi’an Translated by Kathryn Henderson Abstract Two periods in Chinese history can be characterized as constituting a North/South polarization: the period commonly known as the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420AD-589AD), and the Southern Song, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties (1115AD-1368AD). Both of these periods exhibited sharp contrasts between the North and South that can be seen in their respective political and economic institutions. The North/South parity in both of these periods had a great impact on the course of Chinese history. Both before and after the much studied Tang-Song transformation, Chinese history evolved as a conjoining of previously separate North/South institutions. Once the country achieved unification under the Sui Dynasty and early part of the Tang, the trend was to carry on the Northern institutions in the form of political and economic adminis- tration. Later in the Tang Dynasty the Northern institutions and practices gave way to the increasing implementation of the Southern institutions across the country. During the Song Dynasty, the Song court initially inherited this “Southernization” trend while the minority kingdoms of Liao, Xia, Jin, and Yuan primarily inherited the Northern practices. After coexisting for a time, the Yuan Dynasty and early Ming saw the eventual dominance of the Southern institutions, while in middle to late Ming the Northern practices reasserted themselves and became the norm. An analysis of these two periods of North/South disparity will demonstrate how these differences came about and how this constant divergence-convergence influenced Chinese history. -

Late Imperial China

Late Imperial China 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Song dynasty 宋 Middle Imperial Period 960 - 1279 ca. 600-1400 Yuan dynasty 元 1279 - 1368 Ming dynasty 明 Late Imperial Period 1368 - 1644 ca. 1400-1900 Qing dynasty 清 1644 - 1911 Republic of China 中華民國 1911-1949 Post-Dynastic Period People's Republic of China 中華人民共和國 1911-present 1949 - present "Northern Zone" Manchuria Xinjiang Mongolia (E. Turkestan) Ordos Tibetan Plateau China Proper Northern Steppe Mongolia Junggar Basin Xinjiang Autonomous Region Kazakhstan steppe Eurasian Steppe Pastoral Nomadism Inner Mongolia Mongol Empire at its height Temüjin Chinggis (Genghis, Jenghis) Khan ca. 1162-1227 Lake Baikal Manchuria Xinjiang Mongolia (E. Turkestan) Ordos Tibetan Plateau China Proper Mongol Empire Mongol script "Han people" hanren 漢人 "southerners" nanren 南人 Khan Emperor tanistry primogeniture Divisions of Mongol Empire mid 13th century Empire of the Great Khan Khubilai Khan 1215-94 Yuan Dynasty 1279 - 1368 Taizu Capitals of the Yuan Dynasty Karakorum Shangdu Dadu (Beijing) Khubilai Khan on horseback Red Turban Rebellion mid. 14th century White Louts Society millenarianism Maitreya cult Population of China, 2 -1500 CE 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Zhu Yuanzhang 1328-1398 Ming Dynasty 1368-1644 明 Beijing Nanjing The Hongwu Emperor Ming Taizu r. 1368-1398 Ming Empire Great Wall of China 1. Mongol Empire 2. Ming Dynasty 3. Trade and Tribute 4. Foundations of the Qing Dynasty 5. Europeans in China Yongle Emperor Zhu Di r. -

CHINESE CERAMICS and TRADE in 14 CENTURY SOUTHEAST ASIA——A CASE STUDY of SINGAPORE XIN GUANGCAN (BA History, Pekingu;MA Arch

CHINESE CERAMICS AND TRADE IN 14TH CENTURY SOUTHEAST ASIA——A CASE STUDY OF SINGAPORE XIN GUANGCAN (BA History, PekingU;MA Archaeology, PekingU) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2015 Acknowledgements Upon accomplishing the entire work of this thesis, it is time for me to acknowledge many people who have helped me. First, I will like to express my utmost gratitude to my supervisor Dr.John N. Miksic from the Department of Southeast Asian Studies, National University of Singapore. He has dedicated a lot of precious time to supervising me, from choosing the thesis topic, organizing the fieldwork plans, to giving much valued comments and advice on the immature thesis drafts. I am the most indebted to him. The committee member Dr. Patric Daly from the Asian Research Institute and Dr. Yang Bin from the History Department, who gave me useful suggestions during the qualifying examination. I also would like to thank the following people who have given me a lot of support during my fieldwork and final stage of writing. For the fieldtrip in Zhejiang Province, with the help of Mr. Shen Yueming, the director of Zhejiang Relics and Archaeology Institute, I was able to be involved in a meaningful excavation of a Song to Yuan Dynasty ceramic kiln site in Longquan County. During the excavation, the deputy team leader Mr. Xu Jun and the local researcher Mr. Zhou Guanggui gave a lot of suggestions on the identification of Longquan celadon. Moreover, Ms. Wu Qiuhua, Mr. Yang Guanfu, and Mr. -

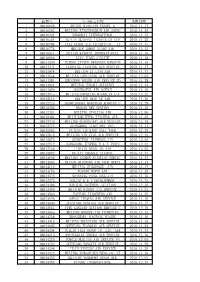

航协号 公司英文名称 1 08010026 Shishi Qiaolian Travel & 2016.11.17 2 08010262 Beijing Xingzhongbin Air Agenc 2016.1

航协号 公司英文名称 到账日期 1 08010026 SHISHI QIAOLIAN TRAVEL & 2016.11.17 2 08010262 BEIJING XINGZHONGBIN AIR AGENC 2016.11.29 3 08010424 SHANGHAI INTERNATIONAL 2016.11.25 4 08010564 GUILIN GUIKANG TICKETS CO LTD 2016.11.25 5 08010704 CIXI XUNDA AIR TICKETS CO., LT 2016.11.15 6 08010774 BEIJING ZHENG XIANG AIR 2016.12.21 7 08010811 FUJIAN KANGTAI INTERNATIONAL 2016.11.16 8 08010833 LIAN JIANG AIRLINE 2016.11.18 9 08011290 FUZHOU JINYUN HANGKONG HANGYUN 2016.11.16 10 08011441 LIAONING JIANTONG AIR SERVICE 2016.11.17 11 08011474 BEIJING ZI LANG AIR 2016.11.22 12 08011544 BEIJING LANYUXING AIR SERVICE 2016.12.01 13 08011581 SHENZHEN YOUSHI AIR SERVICE CO 2016.11.28 14 08011824 BEIJING ZHAORI AVIATION 2016.11.14 15 08011850 SUCCESSFUL AIR AGENCY 2016.11.16 16 08012045 BEIJING HANGTIAN MIANYUAN AIR 2016.12.22 17 08012115 BEIJING QING YE AIR 2016.11.30 18 08012325 QINHUANGDAO HONGYUAN KONGYUN C 2016.11.29 19 08012336 HANDAN NEW CENTURY 2016.11.15 20 08012351 BEIJING JINGJIAO AIR 2016.12.06 21 08012384 BEIJINGRUIFENG XINCHENG AIR 2016.11.25 22 08012443 BEIJING GENERALWAY AIR SERVICE 2016.12.15 23 08012572 GUANGZHOU JIAOYIHUI INTL 2016.11.17 24 08012583 FUJIAN JINJIANG ANLI TOUR 2016.11.28 25 08012642 BEIJING YIN YING AIR SERVICE 2016.12.19 26 08012675 GUANGZHOU TIANWANG AIR 2016.12.05 27 08012712 GUANGDONG JINPENG E & T INDUS 2016.12.22 28 08012756 TIANJIN HONGLIAN AIR 2016.12.02 29 08012992 FUJIAN CHANGLE XIANGYU 2016.11.17 30 08013036 BEIJING ANZHEN AVIATION SERVIC 2016.11.23 31 08013062 HAINAN HAICHENG AIR TOUR SERVI 2016.11.17 32 08013110 BEIJING ZIGUANGGE -

From Empire to Dynasty: the Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming

Furman Humanities Review Volume 30 April 2019 Article 10 2019 From Empire to Dynasty: The Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming Yunhui Yang '19 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Yang, Yunhui '19 (2019) "From Empire to Dynasty: The Imperial Career of Huang Fu in the Early Ming," Furman Humanities Review: Vol. 30 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/fhr/vol30/iss1/10 This Article is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Humanities Review by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FROM EMPIRE TO DYNASTY: THEIMPEJUALCARE ROFH ANGFU IN THE EARLY MING Yunhui Yang In 1511, a Portuguese expeditionary force, captai ned by the brilliant empire builder Afonso de Albuquerque ( 1453-1515) succeeded in establishing a presence in South east Asia with the capture of Malacca, a po1t city of strategic and commercial importance. Jn the colonial "Portuguese cen tury" that followed, soldiers garrisoned coastal forts officials administered these newly colonized territories, merchants en gaged in the lucrative spice trade, Catholic missionaries pros elytized the indigenous people and a European sojourner population settled in Southeast Asia. 1 Although this was the first tim larger numbers of indigenous people in Southeast Asia encountered a European empire , it was not the first co lonial experience for these people. Less than a century be fore the Annamese had been colonized by the Great Ming Empire from China .2 1 Brian Harri on, South-East Asia: A Short Histo,y, 2nd ed.