Rêverie” (Notes, Fragments, and Collage for a Lecture) by Juan José Lahuerta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acción Surrealista Y Medios De Intervención. El Surrealismo En Las Revistas, 1930 – 1939

Acción surrealista y medios de intervención. El surrealismo en las revistas, 1930 – 1939 Javier MAÑERO RODICIO CES Felipe II, Universidad Complutense de Madrid [email protected] Entregado: 19/9/2012 Aceptado: 4/7/2013 RESUMEN Sobre la base de un estudio previo, El surrealismo en las revistas 1919 – 1929, pero de forma autónoma, se aborda a continuación la segunda década surrealista, revisitada siempre al hilo de las revistas que aglutinaron al movimiento. Tras analizar desde Un cadavre la dimensión de la crisis del grupo hacia el cambio de década, asistimos a la adaptación del surrealismo a las extremas condiciones políticas de los años 30 con su revista El surrealismo al servicio de la Revolución. Pero también, y al mismo tiempo, al momento de su máxima difusión y aceptación, particularmente a través del arte. La revista Minotaure será la principal manifestación de este proceso, aunque también son tenidas aquí en cuenta otras cabe- ceras. Palabras clave: Surrealismo, Revistas de arte, A. Breton, G. Bataille, Le surréalisme au service de la Révolution, Documents 34, Minotaure, Cahiers d’Art. Surreal action and means of intervention. Surrealism in the magazines, from 1930 to 1939 ABSTRACT Following on from the previous study, Surrealism in Magazines 1919 – 1929, the second Surrealist decade is now focussed on – at all times with regard to the magazines that united together around the movement. After analysing in Un cadavre the effects of the crisis of 1929, we witness Surrealism’s adap- tation to the extreme political panorama of the 1930’s with the magazine Surrealism in the service of the revolution. -

1 Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida

Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida Integrated Curriculum Tour Form Education Department, 2015 TITLE: “Salvador Dalí: Elementary School Dalí Museum Collection, Paintings ” SUBJECT AREA: (VISUAL ART, LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE, MATHEMATICS, SOCIAL STUDIES) Visual Art (Next Generation Sunshine State Standards listed at the end of this document) GRADE LEVEL(S): Grades: K-5 DURATION: (NUMBER OF SESSIONS, LENGTH OF SESSION) One session (30 to 45 minutes) Resources: (Books, Links, Films and Information) Books: • The Dalí Museum Collection: Oil Paintings, Objects and Works on Paper. • The Dalí Museum: Museum Guide. • The Dalí Museum: Building + Gardens Guide. • Ades, dawn, Dalí (World of Art), London, Thames and Hudson, 1995. • Dalí’s Optical Illusions, New Heaven and London, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2000. • Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 2005. • Anderson, Robert, Salvador Dalí, (Artists in Their Time), New York, Franklin Watts, Inc. Scholastic, (Ages 9-12). • Cook, Theodore Andrea, The Curves of Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1979. • D’Agnese, Joseph, Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, New York, henry Holt and Company, 2010. • Dalí, Salvador, The Secret life of Salvador Dalí, New York, Dover publications, 1993. 1 • Diary of a Genius, New York, Creation Publishing Group, 1998. • Fifty Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, New York, Dover Publications, 1992. • Dalí, Salvador , and Phillipe Halsman, Dalí’s Moustache, New York, Flammarion, 1994. • Elsohn Ross, Michael, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities, Chicago review Press, 2003 (Ages 9-12) • Ghyka, Matila, The Geometry of Art and Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1977. • Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, New York, W.W. -

Of the Omnipotent Mind, Or Surrealism

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The occultation of Surrealism: a study of the relationship between Bretonian Surrealism and western esotericism Bauduin, T.M. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Bauduin, T. M. (2012). The occultation of Surrealism: a study of the relationship between Bretonian Surrealism and western esotericism. Elck Syn Waerom Publishing. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 four Introduction: The unfortunate onset of the 1930s By the end of the 1920s, life was FO turning sour for Breton. Financially, he was floundering. Amorously, he found himself in dire straits: his marriage with Simone Kahn was over, a love affair UR with Lise Meyer had ended badly, his involvement with Nadja had been tragic and the affair with Suzanne Muzard— introduced as ‘X’ at the end of Nadja— The ‘Golden was not going well. -

Documents (Pdf)

Documents_ 18.7 7/18/01 11:40 AM Page 212 Documents 1915 1918 Exhibition of Paintings by Cézanne, Van Gogh, Picasso, Tristan Tzara, 25 poèmes; H Arp, 10 gravures sur bois, Picabia, Braque, Desseignes, Rivera, New York, Zurich, 1918 ca. 1915/16 Flyer advertising an edition of 25 poems by Tristan Tzara Flyer with exhibition catalogue list with 10 wood engravings by Jean (Hans) Arp 1 p. (folded), 15.3x12 Illustrated, 1 p., 24x16 1916 Tristan Tzara lira de ses oeuvres et le Manifeste Dada, Autoren-Abend, Zurich, 14 July 1916 Zurich, 23 July 1918 Program for a Dada event in the Zunfthaus zur Waag Flyer announcing a soirée at Kouni & Co. Includes the 1 p., 23x29 above advertisement Illustrated, 2 pp., 24x16 Cangiullo futurista; Cafeconcerto; Alfabeto a sorpresa, Milan, August 1916 Program published by Edizioni futuriste di “Poesia,” Milan, for an event at Grand Eden – Teatro di Varietà in Naples Illustrated, 48 pp., 25.2x17.5 Pantomime futuriste di Francesco Cangiullo, Rome, 1916 Flyer advertising an event at the Club al Cantastorie 1 p., 35x50 Galerie Dada envelope, Zurich, 1916 1 p., 12x15 Stationary headed ”Mouvement Dada, Zurich,“ Zurich, ca. 1916 1 p., 14x22 Stationary headed ”Mouvement Dada, Zeltweg 83,“ Zurich, ca. 1916 Club Dada, Prospekt des Verlags Freie Strasse, Berlin, 1918 1 p., 12x15 Booklet with texts by Richard Huelsenbeck, Franz Jung, and Raoul Hausmann Mouvement Dada – Abonnement Liste, Zurich, ca. 1916 Illustrated, 16 pp., 27.1x20 Subscription form for Dada publications 1 p., 28x20.5 Centralamt der Dadaistischen Bewegung, Berlin, ca. 1918–19 1917 Stationary of Richard Huelsenbeck with heading of the Sturm Ausstellung, II Serie, Zurich, 14 April 1917 Dada Movement Central Office Catalogue of an exhibition at the Galerie Dada. -

S Religious Artwork

A look at Salvador Dali’s religious artwork The American public loves the later paintings of Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), the Spanish artist who was a leader of the surrealist movement in the 1920s and 1930s but who announced his return to the Catholic faith and a classical style of painting in 1942. But most art critics and a number of theologians have dismissed Dalí’s later work. Some judged his Catholicism as insincere, while others thought Dalí lost his creative spark when he rejected the abstraction of modern art. Thanks to the exhibit “Dalí: The Late Work,” which runs through Jan. 9 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, we can now see Dalí’s later works as continuing the traits that made him such a compelling artist: his devotion to “good” painting (meaning, for him, the ability to accurately reproduce reality in pigments), and his fascination with the intersection of science and mathematics with the subconscious mind. Curator Elliott King told Our Sunday Visitor that Dalí, who was raised Catholic by his mother during his youth in Spain’s Catalan region, never completely left the faith, even though all the surrealists denounced the Church in the 1920s. His first painting to win a prize was a “Basket of Bread,” revealing a lifelong interest in the iconography of bread and its importance in the miracle of the Eucharist. And thanks to theologian Michael Anthony Novak’s analysis of the “Sacrament of the Last Supper” in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., we can also appreciate Dalí’s effort to interpret traditional religious subject matter in a way that expresses both contemporary reality and the central mystery of the Catholic faith. -

Its Principles and Structures in Andre Breton's Nadja, L

The surrealist novel: its principles and structures in André Breton's "Nadja," "L'Amour Fou" and "Arcane 17" Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Lang, Carol Elizabeth Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 12:17:21 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/565482 THE SURREALIST NOVEL: ITS PRINCIPLES AND STRUCTURES IN ANDRE BRETON'S NADJA, L'AMOUR FOU AND ARCANE 17 by Carol Elizabeth Lang A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ROMANCE LANGUAGES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WITH A MAJOR IN FRENCH In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 8 0 Copyright 1980 Carol Elizabeth Lang THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Final Examination Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Carol Elizabeth Lang__________________ entitled The Surrealist Novel: Its Principles and Structures in Andr£ Breton's Nadia, 1*Amour fou and Arcane 17 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor o f Philosophy__________________________ . IjLdjiz. Date ij-- t - £ 0 Date 12. 17- Date Date Date Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate's submission of the final copy of the dissertation to the Graduate College. -

"Dalí Museum: Keeping It Fresh"

National Docent Symposium 2013 "Dalí in the Details: Successful Strategies for Refreshing Your Tours from a Dalínian Perspective" Presented by Peter Tush Dalí Museum Curator of Education Diane Shea Williams Dalí Museum Docent Chair of the Volunteer Council 1) Who is Salvador Dalí? and what makes the Dalí Museum so special? Salvador Dalí Surrealist painter of dreams Salvador Dalí 1904 – 1989 Painter, writer, filmmaker, Surrealist, explorer of the unconscious, Nuclear Mystical painter, designer of ballets, architecture, clothing, book illustrations, album covers, jewelry, and commercials HH Alice Cooper Hologram – 1973 "All my ambition on the pictorial level consists of putting on canvas, with the most imperial fury of precision, the images of concrete irrationality." - Salvador Dalí The Persistence of Memory, 1931, Museum of Modern Art, NY The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition, 1934 Dalí’s Autobiography 1942 Cover – The Persistence of Memory 1931 The Hallucinogenic Toreador 1969-70 The Dalí Museum holds the largest collection of his art outside Spain – with 96 oil paintings and more than 5,000 other works The Basket of Bread, 1926 Reynolds and Eleanor Morse, Dalí Museum founders, with Dalí and his wife Gala D Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope!, 1940 The New Dalí Museum Jewel Box by Tampa Bay Spiral staircase ascends to galleries Dalí believed the spiral shape was nature’s perfect form and symbolized cosmic unity View of Tampa Bay from third floor View of the math garden View of the labyrinth Visitors tie wristbands to the wishing tree to end their visit to the museum with a wish. Voted #1 Attraction in Tampa Bay Area by Trip Advisor and Yelp "Don’t go through without a docent…it really comes to life when a docent explains Dalí’s life, his art, and his fame." "Dalí’s paintings are fascinating. -

Daladier. He Was Handed Over to the Germans and Remained In

DALI´ ,SALVADOR Daladier. He was handed over to the Germans and all the surrealists—the only one who achieved celeb- remained in detention until the end of the war. rity status during his lifetime. Although he pub- lished numerous writings, his most important Despite the violent allegations against him by the contributions were concerned with surrealist paint- then very powerful Communist Party, which never ing. While his name conjures up images of melting forgave him for his attitude toward them in 1939, watches and flaming giraffes, his mature style took Daladier returned to France and to his old post of years to develop. By 1926, Dalı´ had experimented deputy for Vaucluse in June 1946. The Radical Party, with half a dozen styles, including pointillism, pur- however, was only a shadow of its former self, and it ism, primitivism, Marc Chagall’s visionary cubism, fused into a coalition of left-wing parties, the and Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical art. The same Rassemblement des Gauches Re´publicaines, an alli- year, he exhibited the painting Basket of Bread at ance of circumstance with little power. And while the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona, inspired by the Herriot managed to become president of the seventeenth-century artist Francisco de Zurbara´n. National Assembly, Daladier never again played an However, his early work was chiefly influenced by important role. He made his presence felt with his the nineteenth-century realists and by cubist artists opposition to the European Defense Community such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. (EDC), paradoxically holding the same views as the communists. -

Paris, New York and Madrid: Picasso and Dalí Before Great International Exhibitions

Paris, New York and Madrid: Picasso and Dalí before Great International Exhibitions Dalí’s attitude toward Picasso began with admiration, which later became competition, and finally a behavior that, still preserving some features of the former two, also included provocative and exhibitionist harassment, simulated or expressed rivalry, and recognition. As we shall see, this attitude reached its climax at the great international exhibitions. On the other hand, Picasso always stayed away from these provocations and kept a completely opposite, yet watchful and serene behavior toward the impetuous painter from Figueres. Paris 1937, New York 1939 and Madrid 1951: these three occasions in these three major cities are good examples of the climaxes in the Picasso and Dalí confrontation. These international events show their relative divergences, postures, commitments and ways of conceiving art, as well as their positions in relation to Spain. After examining the origins of their relationship, which began in 1926, these three spaces and times shall guide our analysis and discussion of this suggestive relationship. The cultural centers of Madrid, Paris and New York were particularly important in Picasso’s and Dalí’s artistic influence, as well as scenes of their agreements and disagreements. On the one hand, Picasso had already lived in Madrid at the beginning of the 20th century, while Paris had then become the main scene of his artistic development, and New York played a relevant role in his self-promotion. On the other hand, Dalí arrived in Madrid in the early 1920s, and its atmosphere allowed him to get to Paris by the end of this decade, although New York would later become his main advertising and art promotion center. -

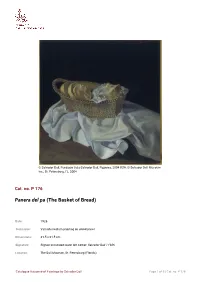

The Basket of Bread)

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2004 USA: © Salvador Dalí Museum Inc., St. Petersburg, FL, 2004 Cat. no. P 176 Panera del pa (The Basket of Bread) Date: 1926 Technique: Varnish medium painting on wood panel Dimensions: 31.5 x 31.5 cm Signature: Signed and dated lower left corner: Salvador Dalí / 1926 Location: The Dali Museum, St. Petersburg (Florida) Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí Page 1 of 5 | Cat. no. P 176 Provenance H. K. Siebeneck, Pittsburgh (Pensylvania) James Thrall Soby, Farmington (Connecticut) E. and A. Reynolds Morse, Cleveland (Ohio) Exhibitions 1926, Barcelona, Galeries Dalmau, Exposició S. Dalí, 31/12/1926 - 14/01/1927, cat. no. 5 1928, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Twenty-Seventh International Exhibition of Paintings, 18/10/1928 - 09/12/1928, cat. no. 361 1932, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, An Exhibition of Carnegie International Paintings Owned in Pittsburgh, 01/11/1932 - 15/12/1932, cat. no. 26 1941, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 19/11/1941 - 11/01/1942, cat. no. 3 1942, Indianapolis, The John Herron Art Institute (Indianapolis Museum of Art), [Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali], 05/04/1942 - 04/05/1942, cat. no. 3 1943, Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts, Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali, 15/03/1943 - 12/04/1943, no reference 1946, Boston, The Institute of Modern Art, Four Spaniards : Dali, Gris, Miro, Picasso, 24/01/1946 - 03/03/1946, cat. no. 1 1965, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 1910-1965, 18/12/1965 - 13/03/1966, cat. no. 18 1983, Barcelona, Palau Reial de Pedralbes, 400 obres de Salvador Dalí del 1914 al 1983, 10/06/1983 - 31/07/1983, cat. -

Salvador Dali 1904-1989

Salvador Dali 1904-1989 Ideas of things to bring to the classroom with you: Salvador Dali presentation CD and script/folder Box with different hats – “A Matter of Style” See end of script for this idea IF you have time. Book Salvador Dali by Dick Venezia from the series, “Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Artists” You can read this book to get a quick overview of Dali’s life and art. You can also read to the class if time allows or just flip through it with them. Introduce yourself and tell the children that you are in today for Art in the Classroom. Before we can begin today, can anyone tell me the important points about the artist you spoke about last time in Art in the Classroom? Spend a minute or two reviewing and then move on. When we look at the artwork that I am going to show you today, let’s keep in mind the tools that an artist uses. “Elements of art page” Line, color, shape, light, texture, space Slide 1 Clues about the personality of today’s artist: He has said: “Nothing is more important to me … than me.” He once arrived at an important event in a Rolls Royce convertible filled with cauliflower. He has also said “Every morning when I wake up I experience the exquisite joy – the joy of being Salvador Dali – and I ask myself in rapture ‘What wonderful things this Salvador Dali will accomplish today?’ ” As you may have guessed, today’s artist, Salvador Dali, is going to be different. -

For André Breton)

Published by Peculiar Mormyrid peculiarmormyrid.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher or author. Texts Copyright © The Authors Images Copyright © The Artists Direction: Angel Therese Dionne, Casi Cline, Steven Cline, Patrik Sampler, Jason Abdelhadi Cover Art by Ody Saban ISBN 978-1-365-09136-0 First Edition 2016 CONTRIBUTORS Jason Abdelhadi Rik Lina Elise Aru Michaël Löwy Johannes Bergmark Renzo Margonari Jay Blackwood Rithika Merchant Anny Bonnin Paul McRandle Bruce Boston Andrew Mendez Maurizio Brancaleoni Steve Morrrison Cassandra Carter David Nadeau Miguel de Carvalho Valery Oisteanu Claude Cauët Ana Orozco Casi Cline Jaan Patterson Steven Cline Toby Penny Paul Cowdell Mitchell Poor Ashley DeFlaminis Evelyn Postic Angel Dionne Jean-Raphaël Prieto Richard Dotson John Richardson Guy Ducornet Penelope Rosemont Alfredo Fernandes Ody Saban Daniel Fierro Ron Sakolsky Mattias Forshage Patrik Sampler Joël Gayraud Nelly Sanchez Guy Girard Mark Sanders Jon Graham Pierre-André Sauvageot Jean-Pierre Guillon Matt Schumacher Janice Hathaway Scheherazade Siobhan Nicholas Hayes Arthur Spota Sherri Higgins Dan Stanciu Dale Houstman Virginia Tentindo Karl Howeth TD Typaldos Stuart Inman Tamara K. Walker James Jackson John Welson Alex Januário Craig Wilson Philip Kane William Wolak Stelli Kerk İzem Yaşın Stephen Kirin Mark Young Megan Leach Michel Zimbacca CONTENTS PAS UN CADAVRE: