S Religious Artwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida

Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida Integrated Curriculum Tour Form Education Department, 2015 TITLE: “Salvador Dalí: Elementary School Dalí Museum Collection, Paintings ” SUBJECT AREA: (VISUAL ART, LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE, MATHEMATICS, SOCIAL STUDIES) Visual Art (Next Generation Sunshine State Standards listed at the end of this document) GRADE LEVEL(S): Grades: K-5 DURATION: (NUMBER OF SESSIONS, LENGTH OF SESSION) One session (30 to 45 minutes) Resources: (Books, Links, Films and Information) Books: • The Dalí Museum Collection: Oil Paintings, Objects and Works on Paper. • The Dalí Museum: Museum Guide. • The Dalí Museum: Building + Gardens Guide. • Ades, dawn, Dalí (World of Art), London, Thames and Hudson, 1995. • Dalí’s Optical Illusions, New Heaven and London, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2000. • Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 2005. • Anderson, Robert, Salvador Dalí, (Artists in Their Time), New York, Franklin Watts, Inc. Scholastic, (Ages 9-12). • Cook, Theodore Andrea, The Curves of Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1979. • D’Agnese, Joseph, Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, New York, henry Holt and Company, 2010. • Dalí, Salvador, The Secret life of Salvador Dalí, New York, Dover publications, 1993. 1 • Diary of a Genius, New York, Creation Publishing Group, 1998. • Fifty Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, New York, Dover Publications, 1992. • Dalí, Salvador , and Phillipe Halsman, Dalí’s Moustache, New York, Flammarion, 1994. • Elsohn Ross, Michael, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities, Chicago review Press, 2003 (Ages 9-12) • Ghyka, Matila, The Geometry of Art and Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1977. • Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, New York, W.W. -

Daladier. He Was Handed Over to the Germans and Remained In

DALI´ ,SALVADOR Daladier. He was handed over to the Germans and all the surrealists—the only one who achieved celeb- remained in detention until the end of the war. rity status during his lifetime. Although he pub- lished numerous writings, his most important Despite the violent allegations against him by the contributions were concerned with surrealist paint- then very powerful Communist Party, which never ing. While his name conjures up images of melting forgave him for his attitude toward them in 1939, watches and flaming giraffes, his mature style took Daladier returned to France and to his old post of years to develop. By 1926, Dalı´ had experimented deputy for Vaucluse in June 1946. The Radical Party, with half a dozen styles, including pointillism, pur- however, was only a shadow of its former self, and it ism, primitivism, Marc Chagall’s visionary cubism, fused into a coalition of left-wing parties, the and Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical art. The same Rassemblement des Gauches Re´publicaines, an alli- year, he exhibited the painting Basket of Bread at ance of circumstance with little power. And while the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona, inspired by the Herriot managed to become president of the seventeenth-century artist Francisco de Zurbara´n. National Assembly, Daladier never again played an However, his early work was chiefly influenced by important role. He made his presence felt with his the nineteenth-century realists and by cubist artists opposition to the European Defense Community such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. (EDC), paradoxically holding the same views as the communists. -

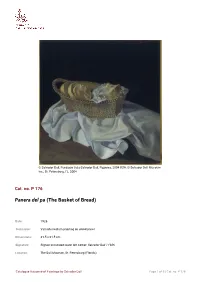

The Basket of Bread)

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2004 USA: © Salvador Dalí Museum Inc., St. Petersburg, FL, 2004 Cat. no. P 176 Panera del pa (The Basket of Bread) Date: 1926 Technique: Varnish medium painting on wood panel Dimensions: 31.5 x 31.5 cm Signature: Signed and dated lower left corner: Salvador Dalí / 1926 Location: The Dali Museum, St. Petersburg (Florida) Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí Page 1 of 5 | Cat. no. P 176 Provenance H. K. Siebeneck, Pittsburgh (Pensylvania) James Thrall Soby, Farmington (Connecticut) E. and A. Reynolds Morse, Cleveland (Ohio) Exhibitions 1926, Barcelona, Galeries Dalmau, Exposició S. Dalí, 31/12/1926 - 14/01/1927, cat. no. 5 1928, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Twenty-Seventh International Exhibition of Paintings, 18/10/1928 - 09/12/1928, cat. no. 361 1932, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, An Exhibition of Carnegie International Paintings Owned in Pittsburgh, 01/11/1932 - 15/12/1932, cat. no. 26 1941, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 19/11/1941 - 11/01/1942, cat. no. 3 1942, Indianapolis, The John Herron Art Institute (Indianapolis Museum of Art), [Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali], 05/04/1942 - 04/05/1942, cat. no. 3 1943, Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts, Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali, 15/03/1943 - 12/04/1943, no reference 1946, Boston, The Institute of Modern Art, Four Spaniards : Dali, Gris, Miro, Picasso, 24/01/1946 - 03/03/1946, cat. no. 1 1965, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 1910-1965, 18/12/1965 - 13/03/1966, cat. no. 18 1983, Barcelona, Palau Reial de Pedralbes, 400 obres de Salvador Dalí del 1914 al 1983, 10/06/1983 - 31/07/1983, cat. -

Salvador Dali 1904-1989

Salvador Dali 1904-1989 Ideas of things to bring to the classroom with you: Salvador Dali presentation CD and script/folder Box with different hats – “A Matter of Style” See end of script for this idea IF you have time. Book Salvador Dali by Dick Venezia from the series, “Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Artists” You can read this book to get a quick overview of Dali’s life and art. You can also read to the class if time allows or just flip through it with them. Introduce yourself and tell the children that you are in today for Art in the Classroom. Before we can begin today, can anyone tell me the important points about the artist you spoke about last time in Art in the Classroom? Spend a minute or two reviewing and then move on. When we look at the artwork that I am going to show you today, let’s keep in mind the tools that an artist uses. “Elements of art page” Line, color, shape, light, texture, space Slide 1 Clues about the personality of today’s artist: He has said: “Nothing is more important to me … than me.” He once arrived at an important event in a Rolls Royce convertible filled with cauliflower. He has also said “Every morning when I wake up I experience the exquisite joy – the joy of being Salvador Dali – and I ask myself in rapture ‘What wonderful things this Salvador Dali will accomplish today?’ ” As you may have guessed, today’s artist, Salvador Dali, is going to be different. -

Rêverie” (Notes, Fragments, and Collage for a Lecture) by Juan José Lahuerta

©Juan José Lahuerta, 2007 & 2016 “Rêverie” (notes, fragments, and collage for a lecture) by Juan José Lahuerta - “Rêverie” was published in Le Surréalisme au Service de la Révolution, no. 4, Paris, December 1931, pp. 31-36. - Issues 3 and 4 appeared simultaneously in December 1931. Dalí also contributed to issue 3 with the major article “Objets surréalistes” and a note on “Visage Paranoïaque,” together with a postcard about Picasso’s “black period.” - Both of these issues have a distinct political bent; for example, no. 3 opens with the long Aragon article “Le surréalisme et le devenir révolutionnaire.” Thus a certain tension arises between Dalí’s contributions, particularly “Rêverie,” and this strongly political vein. - The consequences of publishing this “story,” if it can be called that, must be understood within the context of this tension. In fact, these consequences had a significant impact on the Surrealists, since the piece helped spark the definitive break between Breton and Aragon. Once it was published, the story’s pornographic nature caused a considerable scandal, to the point that Surrealists who were members of the Communist Party were called before a commission that demanded explanations of them. Shortly thereafter, in March of 1932, Éditions Surréalistes published Breton’s plaquette Misère de la poésie. Its objective was to defend Aragon, who found himself embroiled in legal and police proceedings following publication of the poem “The Red Front.” In this plaquette, however, and contrary to party directives and the ambiguous position of Aragon himself, Breton defended such things as the complementary relationship between dialectic thought and Freudian analysis. -

Dali Keynote

Dali’s father, Salvador Dali i Cusi, was a notary. His mother, Felipa Domenech Ferres, was a homemaker. Salvador Domingo Felipe Dali was born in 1904. His older brother with the same name died a year before his birth. At five, Dali’s mother told him that he was a REINCARNATION OF HIS BROTHER. Dali believed this. At five, Dali wanted to be a cook. At six, Dali painted a landscape and wanted to become an artist. At seven, Dali wanted to become Napoleon (they had a portrait of Napoleon in their home). Dali’s boyhood was in Figueres (Fee-yair-ez), Spain, a town near Barcelona. This church is where Dali was baptized and eventually where his funeral was held. Summers were spent in the tiny fishing village of Cadaques (Ka-da-kiz). Dali loved the sea and the image of it shows up frequently in his paintings. Local legends suggested that the howling winds and twisted yellow terrain of the region in Catalonia would eventually make a man mad! With sister Ana Maria Later with his wife With poet friend Lorca Photos from Cadaques Dali attended drawing school. While in Cadaques, he discovered modern painting. His father organized an exhibition of his charcoal drawings in his family home. At 15, Dali had his first public exhibition of his art. When he was 16, Dali’s mother died of cancer. He later said that this was the “greatest blow I had experienced in life. I worshipped her.” Dali was accepted into the San Fernando Academy of Art in Madrid. -

1 Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida

Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida Integrated Curriculum Tour Form Education Department, 2014 TITLE: “Salvador Dalí: Middle School Dalí Museum Collection, Paintings” SUBJECT AREA: (VISUAL ART, LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE, MATHEMATICS, SOCIAL STUDIES) Visual Art (Next Generation Sunshine State Standards listed at the end of this document) GRADE LEVEL(S): Grades: 6-8 DURATION: (NUMBER OF SESSIONS, LENGTH OF SESSION) One session (30 to 45 minutes) Resources: (Books, Links, Films and Information) Books: • The Dalí Museum Collection: Oil Paintings, Objects and Works on Paper. • The Dalí Museum: Museum Guide. • The Dalí Museum: Building + Gardens Guide. • Ades, dawn, Dalí (World of Art), London, Thames and Hudson, 1995. • Dalí’s Optical Illusions, New Heaven and London, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2000. • Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 2005. • Anderson, Robert, Salvador Dalí, (Artists in Their Time), New York, Franklin Watts, Inc. Scholastic, (Ages 9-12). • Cook, Theodore Andrea, The Curves of Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1979. • D’Agnese, Joseph, Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, New York, henry Holt and Company, 2010. • Dalí, Salvador, The Secret life of Salvador Dalí, New York, Dover publications, 1993. 1 • Diary of a Genius, New York, Creation Publishing Group, 1998. • Fifty Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, New York, Dover Publications, 1992. • Dalí, Salvador , and Phillipe Halsman, Dalí’s Moustache, New York, Flammarion, 1994. • Elsohn Ross, Michael, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities, Chicago review Press, 2003 (Ages 9-12) • Ghyka, Matila, The Geometry of Art and Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1977. • Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, New York, W.W. -

Antenna International the Dalí Museum Permanent Collection Adult Tour Press Script

Antenna International The Dalí Museum Permanent Collection Adult Tour Press Script Antenna Audio 2010 | The Dali Museum Adult Press Script Stop 1 Introduction, Enigma Hall Stop 1-02 Architecture Stop 99 Player Instructions Stop 2 Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope!, 1940 Stop 3 View of Cadaqués with Shadow of Mount Paní, 1917 Stop 4 Self-Portrait (Figueres), 1921 Stop 5 Cadaqués, 1923 Stop 6 Portrait of My Sister, 1923 Stop 7 The Basket of Bread, 1926 Stop 8 Girl with Curls, 1926 Stop 9 Portrait of My Dead Brother, 1963 Stop 10 Apparatus and Hand, 1927 Stop 10-02 Apparatus and Hand, 1927 [Second Level] Stop 11 Gala Contemplating the Mediterranean Sea which at Twenty Meters Becomes the Portrait of Abraham Lincoln - Homage to Rothko (Second Version), 1976 Stop 12 Nature Morte Vivante (Still Life – Fast Moving), 1956 Stop 13 The Average Bureaucrat, 1930 Stop 14 The First Days of Spring, 1929 Stop 15 Eggs on the Plate Without the Plate, 1932 Stop 16 Archeological Reminiscence of Millet’s ―Angelus,‖ 1933-35 Stop 17 Enchanted Beach with Three Fluid Graces, 1938 Stop 18 The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition, 1934 Stop 19 The Discovery of America by Christopher Columbus, 1958 Stop 20 The Hallucinogenic Toreador, 1969-1970 Stop 20-02 The Hallucinogenic Toreador, 1969-1970 [Second Level] Stop 21 Geopoliticus Child Watching the Birth of the New Man, 1943 Stop 22 Old Age, Adolescence, Infancy (The Three Ages), 1940 Stop 23 Slave Market with the Disappearing Bust of Voltaire, 1940 Antenna Audio 2010 | The Dali Museum Adult Press Script Stop 24 The -

Salvador Dalí, Surrealism, and the Luxury Fashion Industry

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2016 Salvador Dalí, Surrealism, and the Luxury Fashion Industry Chantal Houglan College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Contemporary Art Commons, Modern Languages Commons, and the Theory and Criticism Commons Recommended Citation Houglan, Chantal, "Salvador Dalí, Surrealism, and the Luxury Fashion Industry" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 902. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/902 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Houglan 2 For both my mother, Nicole Houglan, who introduced me to the Surrealist’s work at a young age and for the Great Dalí, the artist who continues to captivate and spur my imagination, providing me with a creative outlet during my most trying times. Houglan 3 Table of Contents Introduction…................................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1. Dalí’s Self-Fashioning into a Surrealist Spectacle.........................................................8 Chapter 2. Dressing the Self and the Female Figure.....................................................................28 Chapter 3. Dalí’s -

Salvador Dalí Checklist – Philadelphia Museum of Art

Salvador Dalí Checklist – Philadelphia Museum of Art Impressions of Africa 1938 Oil on canvas Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam Self-Portrait with the Neck of Raphael 1920–21 Oil on canvas Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, Spain. Gift of Dalí to the Spanish State View of Cadaqués from Mount Pani 1917 Oil on burlap Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida Portrait of the Cellist Ricardo Pichot 1920 Oil on canvas Private Collection Self-Portrait c. 1921 Oil on cardboard Private Collection Self-Portrait in the Studio 1918–19 Oil on canvas Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida Portrait of My Father 1920–21 Oil on canvas Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, Spain. Gift of Dalí to the Spanish State Port of Cadaqués (Night) 1918–19 Oil on canvas Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida 1 Portrait of Grandmother Ana Sewing 1921 Oil on burlap Collection of Dr. Joaquín Vila Moner The Lane to Port Lligat with View of Cap Creus 1922–23 Oil on canvas Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, Doña Felipa Domènech de Dalí 1920 Pastel on paper on cardboard Private Collection Portrait of Señor Pancraci c. 1919 Oil on canvas Private Collection The Basket of Bread 1926 Oil on panel Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida Fiesta at the Hermitage c. 1921 Oil and gouache on cardboard Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, Spain Head of a Girl 1924 Monotype and etching on paper Collection of Lawrence Saphire Figure at a Table (Portrait of My Sister) 1925 Oil on cardboard Private Collection The First Days of Spring 1922–23 Ink and gouache on paper Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, Spain 2 The Windmill—Landscape near Cadaqués 1923 Oil and gouache on cardboard Private Collection Study for “Portrait of Manuel de Falla” 1924–25 Pencil on paper Salvador Dalí Museum, Inc., Saint Petersburg, Florida Woman at the Window at Figueres 1926 Oil on panel Gala-Salvador Dalí Foundation, Figueres, Spain Federico Lorca in the Café de Oriente with a Guitar c. -

Chapter 11: Salvador Dalí and the Spanish Baroque: from Still Life To

©William Jeffett, 2007 & 2016 Dalí and the Spanish Baroque: From Still Life to Velázquez by William Jeffett Dalí famously turned to baroque modes of representation in the years after World War II, first with The Madonna of Port Lligat (1949) and more dramatically with Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951), both of which announced a new style that dominated his work during the 1950s. These paintings were followed by Eucharistic Still Life (1952) and Corpus Hypercubus (Crucifixion) (1954), which adopted conventional religious subjects as their themes and represented them in a pictorial language distinct from that of Surrealism. Dalí’s new strategy notably deployed stylistic characteristics associated with the Baroque art of Spain’s Golden Age, especially the works of Alonso Cano, Sánchez Cotán, El Greco, Blas de Ledesma, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Jusepe de Ribera, Diego Velázquez, and Francisco Zurbarán. In 1958, Dalí’s Velázquez Painting the Infanta Margarita with the Lights and Shadows of His Own Glory made specific reference not to a religious theme but rather to court painting during the reign of Philip IV and its greatest practitioner of the seventeenth century, Velázquez. Dalí thus cast himself in the role of the greatest living painter of his age, and two years later gave visual representation to this stance in The Ecumenical Council (1960), which quotes Las Meninas (1656) and substitutes his own figure for that of Velázquez. While this period of Dalí’s work is conventionally seen in opposition to his earlier Surrealist period (1929–39), the artist remained rooted in Surrealism and other intellectual strands of modern thought that had reassessed the baroque. -

The Dalí Theatre-Museum: the Result of an Artist's Obsessive Zeal For

The Dalí Theatre-Museum: the result of an artist’s obsessive zeal for research Montse Aguer i Teixidor Director of the Centre for Dalinian Studies Revista de Girona, year L, number 222, january-february 2004 The Dalí Theatre-Museum in Figueres is a unique space, a museographical model based on the artist’s conception of enhancing the semantic possibilities of his own creation, an outstanding work of art which gives priority to concepts and ideas over chronological historicism, an original outlook … just part of what we find here and need to know in order to understand the whole. When Dalí created his total masterpiece, his great surrealist object, his self-designated “ready-made” space, he distanced himself once again from the fashion of the time and offered a centre full of evocations, statements and provocations that never fail to arouse the interest of the visitor-spectator. In the Museum, the building itself shapes the general outline of Dalinian creativity, offering visitors a journey through Salvador Dalí’s personal and artistic trajectory, from both the surrealist approach to art exhibition and that of Dalí himself. We can see works from each of Dalí’s artistic periods, from the early impressionist, cubist, pointillist and fauvist paintings to his surrealist, classicist and mystical-nuclear periods, with the latter works linked to the scientific progress of the age. Also displayed here are paintings from his last 1980-1983 period, during which Dalí reclaimed the great classical masters, notably Michelangelo and Velázquez. Here we find Dalí at his most provocative, Dalí the mystic, Dalí the set designer, Dalí the science enthusiast and, above all, the Dalí of the final period.