Antenna International the Dalí Museum Permanent Collection Adult Tour Press Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Symbolism in Salvador Dali's Art: a Study of the Influences on His Late Work

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2012 Religious Symbolism in Salvador Dali's Art: A Study of the Influences on His Late Work. Jessica R. Hawley East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation Hawley, Jessica R., "Religious Symbolism in Salvador Dali's Art: A Study of the Influences on His Late Work." (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 34. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/34 This Honors Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ’ A t: A Study of the Influences on His Late Work Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors By Jessica Hawley The Honors College Fine and Performing Art Scholars Program East Tennessee State University April 6, 2012 Dr. Scott Contreras-Koterbay, Faculty Mentor Dr. Peter Pawlowicz, Faculty Reader Patrick Cronin, Faculty Reader Hawley 2 Table of Contents Preface 3 Chapter 1: ’ Ch h 4 Chapter 2: Surrealism 7 Chapter 3: War 10 Chapter 4: Catholicism 12 Chapter 5: Nuclear Mysticism 15 Conclusion 18 Images 19 Bibliography 28 Hawley 3 Preface Salvador was an artist who existed not long before my generation; yet, his influence among the contemporary art world causes many people to take a closer look at the significance of the imagery in his paintings. -

Salvador Dalí February 16 – May 15, 2005

Philadelphia Museum of Art Salvador Dalí February 16 – May 15, 2005 TEACHER RESOURCE MATERIALS: IMAGE PROGRAM These fourteen images represent only a small sample of the wide range of works by Salvador Dalí featured in the exhibition. These materials are intended for use in your classroom before, after or instead of visiting the exhibition. These materials were prepared for use with grades 6 through 12. Therefore, you may need to adapt the information to the particular level of your students. Please note that some of the images included in this program contain nudity and/or violence and may not be appropriate for all ages and audiences. SALVADOR DALÍ Philippe Halsman 1942 Photograph Phillipe Halsman Estate, Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. Dalí Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), Dalí, Gala-Salvador © 2004 Salvador Discussion Questions: • Describe the way Dalí appears in the photograph. • What do you think Dalí would say if he could speak? This portrait of Dalí was made when the artist was 38 years old. Philippe Halsman, a friend of Dalí’s, photographed the image, capturing the artist’s face animated by a maniacal expression. Since his days as an art student at the Academy in Madrid, Dalí had enjoyed dressing in an eccentric way to exhibit his individuality and artistic genius. In this portrait Dalí’s mustache, styled in two symmetrical curving arcs, enhances the unsettling expressiveness of his face. Dalí often treated his long mustache as a work of art, sculpting the hairs into the curve of a rhinoceros horn or weaving dollar bills into it. Unlike many of Dalí’s other relationships, his friendship with Halsman was quite stable, spanning more than three decades. -

1 Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida

Dalí Museum, Saint Petersburg, Florida Integrated Curriculum Tour Form Education Department, 2015 TITLE: “Salvador Dalí: Elementary School Dalí Museum Collection, Paintings ” SUBJECT AREA: (VISUAL ART, LANGUAGE ARTS, SCIENCE, MATHEMATICS, SOCIAL STUDIES) Visual Art (Next Generation Sunshine State Standards listed at the end of this document) GRADE LEVEL(S): Grades: K-5 DURATION: (NUMBER OF SESSIONS, LENGTH OF SESSION) One session (30 to 45 minutes) Resources: (Books, Links, Films and Information) Books: • The Dalí Museum Collection: Oil Paintings, Objects and Works on Paper. • The Dalí Museum: Museum Guide. • The Dalí Museum: Building + Gardens Guide. • Ades, dawn, Dalí (World of Art), London, Thames and Hudson, 1995. • Dalí’s Optical Illusions, New Heaven and London, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2000. • Dalí, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Rizzoli, 2005. • Anderson, Robert, Salvador Dalí, (Artists in Their Time), New York, Franklin Watts, Inc. Scholastic, (Ages 9-12). • Cook, Theodore Andrea, The Curves of Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1979. • D’Agnese, Joseph, Blockhead, the Life of Fibonacci, New York, henry Holt and Company, 2010. • Dalí, Salvador, The Secret life of Salvador Dalí, New York, Dover publications, 1993. 1 • Diary of a Genius, New York, Creation Publishing Group, 1998. • Fifty Secrets of Magic Craftsmanship, New York, Dover Publications, 1992. • Dalí, Salvador , and Phillipe Halsman, Dalí’s Moustache, New York, Flammarion, 1994. • Elsohn Ross, Michael, Salvador Dalí and the Surrealists: Their Lives and Ideas, 21 Activities, Chicago review Press, 2003 (Ages 9-12) • Ghyka, Matila, The Geometry of Art and Life, New York, Dover Publications, 1977. • Gibson, Ian, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dalí, New York, W.W. -

Universidade Federal De Goiás Centro De Ensino E Pesquisa Aplicada À Educação

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS CENTRO DE ENSINO E PESQUISA APLICADA À EDUCAÇÃO SANTIAGO LEMOS JOGO VIRTUAL DALÍ EX: FORMAÇÃO ESTÉTICA E ENSINO DE ARTES VISUAIS GOIÂNIA 2017 SANTIAGO LEMOS JOGO VIRTUAL DALÍ EX: FORMAÇÃO ESTÉTICA E ENSINO DE ARTES VISUAIS Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ensino na Educação Básica do Centro de Ensino e Pesquisa Aplicada à Educação da Universidade Federal de Goiás, para obtenção do título de Mestre em Ensino na Educação Básica. Área de Concentração: Ensino na Educação Básica. Linha de Pesquisa: Concepções teórico- metodológicas e práticas docentes. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Maria Alice de Sousa Carvalho Rocha. GOIÂNIA 2017 ÿÿ ÿÿÿÿÿ ÿ !"ÿ #$%ÿÿ&ÿ' %( ÿÿ)" %ÿÿ0 "ÿÿ1&2 7%"ÿ) $ ÿÿÿÿÿÿ89&9ÿ@ABC1'7ÿ4'7DÿEFGÿH% " IÿGÿ9BP'QR9ÿE)CSCA3'ÿE ET)AT9ÿ4Eÿ'BCE)ÿ@A)1'A)ÿUÿ) $ÿ7%"2ÿVÿWXY62 ÿÿÿÿÿÿÿ6Xÿ2Gÿ2 ÿÿÿÿÿÿ9 Gÿ#2ÿPÿ'ÿÿÿ)"ÿ3 ÿBÿ2 ÿÿÿÿÿÿ4"" ÿ`P" aÿVÿ1 "ÿÿÿ&("ÿ3 ÿ#"b"ÿ'ÿcÿEÿ`3E#'Eaÿ#$%ÿÿ#d"V& %ÿE " ÿ ÿEÿ0("ÿ`#"" aÿ&e ÿWXY62 ÿÿÿÿÿ0$2 ÿÿ ÿÿÿÿÿÿY2ÿE " 2ÿW2ÿEÿ0("2ÿ52ÿ' "ÿ@""2ÿf2ÿ8$ÿ4$ 2ÿA2 ÿ)"ÿ3 ÿBÿÿPÿ'ÿÿ 2ÿAA2ÿCg 2 341ÿ56 RESUMO Ao refletir sobre a formação do estudante na sociedade da era digital, observa-se a necessidade de aproveitar os recursos por ela disponibilizados para contribuir com os processos de ensino/aprendizagem dentro e fora de sala de aula. A maioria desses jovens tem cada vez mais contato com os dispositivos de tecnologia móvel como celulares e tablets. Eles utilizam essas ferramentas cotidianamente para acessar as redes sociais e também para participarem de jogos. Esses últimos, segundo pesquisas, são os mais procurados e existem numa grande variedade, mas poucos deles exploram temáticas de interesse educacional. -

Exhibition Checklist

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST Dalí: Painting and Film June 29 – September 15, 2008 Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Madrid Night Scene, 1922 Gouache and watercolor on paper 8 1/4 x 6" (21 x 15.2 cm) Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Brothel, 1922 Gouache on paper 8 3/16 x 5 7/8" (20.8 x 15 cm) Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Summer Night, 1922 Gouache on paper 8 3/16 x 5 7/8" (20.8 x 15 cm) Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 The Drunkard, 1922 Gouache on paper 8 3/16 x 5 7/8" (20.8 x 15 cm) Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Madrid Suburb, circa 1922-23 Gouache on paper 8 3/16 x 5 7/8" (20.8 x 15 cm) Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Portrait of Luis Buñuel, 1924 Oil on canvas 26 15/16 x 23 1/16" (68.5 x 58.5 cm) Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Portrait of my Father, 1925 Oil on canvas 41 1/8 x 41 1/8" (104.5 x 104.5 cm) Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 The Marriage of Buster Keaton, 1925 Collage and ink on paper 8 3/8 x 6 5/8" (21.2 x 16.8 cm) Fundación Federico García Lorca, Madrid Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Penya segats (Woman on the Rocks), 1926 Oil on panel 10 5/8 x 16 1/8" (27 x 41 cm) Private collection Print Date: 06/20/2008 01:22 PM Page 1 of 15 Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 The Hand, 1927 India ink on paper 7 1/2 x 8 1/4" (19 x 21 cm) Private collection Salvador Dalí, Spanish, 1904-1989 Apparatus and Hand, 1927 Oil on panel 24 1/2 x 18 3/4" (62.2 x 47.6 cm) Salvador Dalí Museum, St. -

Memories & Dreams

Memories & Dreams The Studiowith with Salvador Dalí ART HIST RY KIDS WEEK 2 Quote to ponder “Every morning upon awakening, I experience a supreme pleasure: that of being Salvador Dalí, and I ask myself, wonderstruck, what prodigious thing will he do today, this Salvador Dalí?” –Salvador Dalí January 2021 15 Memories & Dreams The Studiowith with Salvador Dalí ART HIST RY KIDS LET’S MEET THE ARTIST Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domenech May 11, 1904 — January 23, 1989 Salvador Dali was born in Figueres– a town in the Catalonia region of Spain. He grew up with a strict father and lenient mother (who encouraged his artistic endeavors and supported his creative personality). She even let him have a pet bat! Dali studied art in Spain and later in Paris where he met legendary painters (like Picasso) who influenced his work. He soon became involved with the Surrealist art movement. In addition to his art, Dali was also known for his funny personality and unusual public behavior. He had outrageous pets, including an ocelot named Babou who never left his side. He took Babou into restaurants and even on plane trips! Sometimes he’d tell people that Babou was just a normal cat that he had painted. He walked around Paris with his pet anteater on a leash. He grew a unique mus- tache and shaped it with pomade. (In 2010 Dali’s mustache was voted the most famous mustache of all time.) Terry Fincher/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images Dali’s transformed his daily life into a surreal piece of art. -

S Religious Artwork

A look at Salvador Dali’s religious artwork The American public loves the later paintings of Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), the Spanish artist who was a leader of the surrealist movement in the 1920s and 1930s but who announced his return to the Catholic faith and a classical style of painting in 1942. But most art critics and a number of theologians have dismissed Dalí’s later work. Some judged his Catholicism as insincere, while others thought Dalí lost his creative spark when he rejected the abstraction of modern art. Thanks to the exhibit “Dalí: The Late Work,” which runs through Jan. 9 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, we can now see Dalí’s later works as continuing the traits that made him such a compelling artist: his devotion to “good” painting (meaning, for him, the ability to accurately reproduce reality in pigments), and his fascination with the intersection of science and mathematics with the subconscious mind. Curator Elliott King told Our Sunday Visitor that Dalí, who was raised Catholic by his mother during his youth in Spain’s Catalan region, never completely left the faith, even though all the surrealists denounced the Church in the 1920s. His first painting to win a prize was a “Basket of Bread,” revealing a lifelong interest in the iconography of bread and its importance in the miracle of the Eucharist. And thanks to theologian Michael Anthony Novak’s analysis of the “Sacrament of the Last Supper” in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., we can also appreciate Dalí’s effort to interpret traditional religious subject matter in a way that expresses both contemporary reality and the central mystery of the Catholic faith. -

Salvador Dali Biography

SALVADOR DALI BIOGRAPHY • Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dali Domenech • born: 11th May 1904 in Figueras • at ten he painted a self- portreit titled "Ill Child” • expelled from San Fernando School of Fine Art • twice expelled from the Royal Academy in Madrid • joined Paris surrealist group • first surrealist painting ”Honey is sweeter than blood” • painted the world of the unconscious • met Gala Helena Deluviana Diakonoff Eluard Honey is sweeter than blood • expelled from the surrealist group • contoversial auto-biography "the secret life of Salvador Dali” • Gala's death in 1982 • Dali's health began to fail • 1983 - last work, "The Swallow´s Tail” • January 23, 1989, Salvador Dali died from heart failure and respiratory complications • buried in the crypt-mausoleum of the Museum Theatre in Galatea Figueras. SECRET LIFE • autobiography The secret life of Salvador Dali • marketing a product - his own art • "The difference between false memories and true ones is the same as for jewels: it is always the false ones that look the most real, the most brilliant." The secret life of Salvador Dali - cover • "It is not important what you do as long as you are in the headlines." • ”Disorder has to be created systematically." • “The only diference between me and a mad man is that I am not mad.” • 5 years: - pushed a little boy of a bridge - put a dead bat coverd with ants in his mouth and bit it in half • 6 years: kicks his three- year old sister in the head • “When I was six years old I wanted to be a cook and when I was seven, Napoleon. -

"Dalí Museum: Keeping It Fresh"

National Docent Symposium 2013 "Dalí in the Details: Successful Strategies for Refreshing Your Tours from a Dalínian Perspective" Presented by Peter Tush Dalí Museum Curator of Education Diane Shea Williams Dalí Museum Docent Chair of the Volunteer Council 1) Who is Salvador Dalí? and what makes the Dalí Museum so special? Salvador Dalí Surrealist painter of dreams Salvador Dalí 1904 – 1989 Painter, writer, filmmaker, Surrealist, explorer of the unconscious, Nuclear Mystical painter, designer of ballets, architecture, clothing, book illustrations, album covers, jewelry, and commercials HH Alice Cooper Hologram – 1973 "All my ambition on the pictorial level consists of putting on canvas, with the most imperial fury of precision, the images of concrete irrationality." - Salvador Dalí The Persistence of Memory, 1931, Museum of Modern Art, NY The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition, 1934 Dalí’s Autobiography 1942 Cover – The Persistence of Memory 1931 The Hallucinogenic Toreador 1969-70 The Dalí Museum holds the largest collection of his art outside Spain – with 96 oil paintings and more than 5,000 other works The Basket of Bread, 1926 Reynolds and Eleanor Morse, Dalí Museum founders, with Dalí and his wife Gala D Daddy Longlegs of the Evening – Hope!, 1940 The New Dalí Museum Jewel Box by Tampa Bay Spiral staircase ascends to galleries Dalí believed the spiral shape was nature’s perfect form and symbolized cosmic unity View of Tampa Bay from third floor View of the math garden View of the labyrinth Visitors tie wristbands to the wishing tree to end their visit to the museum with a wish. Voted #1 Attraction in Tampa Bay Area by Trip Advisor and Yelp "Don’t go through without a docent…it really comes to life when a docent explains Dalí’s life, his art, and his fame." "Dalí’s paintings are fascinating. -

Daladier. He Was Handed Over to the Germans and Remained In

DALI´ ,SALVADOR Daladier. He was handed over to the Germans and all the surrealists—the only one who achieved celeb- remained in detention until the end of the war. rity status during his lifetime. Although he pub- lished numerous writings, his most important Despite the violent allegations against him by the contributions were concerned with surrealist paint- then very powerful Communist Party, which never ing. While his name conjures up images of melting forgave him for his attitude toward them in 1939, watches and flaming giraffes, his mature style took Daladier returned to France and to his old post of years to develop. By 1926, Dalı´ had experimented deputy for Vaucluse in June 1946. The Radical Party, with half a dozen styles, including pointillism, pur- however, was only a shadow of its former self, and it ism, primitivism, Marc Chagall’s visionary cubism, fused into a coalition of left-wing parties, the and Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical art. The same Rassemblement des Gauches Re´publicaines, an alli- year, he exhibited the painting Basket of Bread at ance of circumstance with little power. And while the Dalmau Gallery in Barcelona, inspired by the Herriot managed to become president of the seventeenth-century artist Francisco de Zurbara´n. National Assembly, Daladier never again played an However, his early work was chiefly influenced by important role. He made his presence felt with his the nineteenth-century realists and by cubist artists opposition to the European Defense Community such as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. (EDC), paradoxically holding the same views as the communists. -

Paris, New York and Madrid: Picasso and Dalí Before Great International Exhibitions

Paris, New York and Madrid: Picasso and Dalí before Great International Exhibitions Dalí’s attitude toward Picasso began with admiration, which later became competition, and finally a behavior that, still preserving some features of the former two, also included provocative and exhibitionist harassment, simulated or expressed rivalry, and recognition. As we shall see, this attitude reached its climax at the great international exhibitions. On the other hand, Picasso always stayed away from these provocations and kept a completely opposite, yet watchful and serene behavior toward the impetuous painter from Figueres. Paris 1937, New York 1939 and Madrid 1951: these three occasions in these three major cities are good examples of the climaxes in the Picasso and Dalí confrontation. These international events show their relative divergences, postures, commitments and ways of conceiving art, as well as their positions in relation to Spain. After examining the origins of their relationship, which began in 1926, these three spaces and times shall guide our analysis and discussion of this suggestive relationship. The cultural centers of Madrid, Paris and New York were particularly important in Picasso’s and Dalí’s artistic influence, as well as scenes of their agreements and disagreements. On the one hand, Picasso had already lived in Madrid at the beginning of the 20th century, while Paris had then become the main scene of his artistic development, and New York played a relevant role in his self-promotion. On the other hand, Dalí arrived in Madrid in the early 1920s, and its atmosphere allowed him to get to Paris by the end of this decade, although New York would later become his main advertising and art promotion center. -

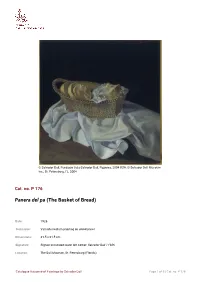

The Basket of Bread)

© Salvador Dalí, Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí, Figueres, 2004 USA: © Salvador Dalí Museum Inc., St. Petersburg, FL, 2004 Cat. no. P 176 Panera del pa (The Basket of Bread) Date: 1926 Technique: Varnish medium painting on wood panel Dimensions: 31.5 x 31.5 cm Signature: Signed and dated lower left corner: Salvador Dalí / 1926 Location: The Dali Museum, St. Petersburg (Florida) Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings by Salvador Dalí Page 1 of 5 | Cat. no. P 176 Provenance H. K. Siebeneck, Pittsburgh (Pensylvania) James Thrall Soby, Farmington (Connecticut) E. and A. Reynolds Morse, Cleveland (Ohio) Exhibitions 1926, Barcelona, Galeries Dalmau, Exposició S. Dalí, 31/12/1926 - 14/01/1927, cat. no. 5 1928, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, Twenty-Seventh International Exhibition of Paintings, 18/10/1928 - 09/12/1928, cat. no. 361 1932, Pittsburgh, Carnegie Institute, An Exhibition of Carnegie International Paintings Owned in Pittsburgh, 01/11/1932 - 15/12/1932, cat. no. 26 1941, New York, The Museum of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 19/11/1941 - 11/01/1942, cat. no. 3 1942, Indianapolis, The John Herron Art Institute (Indianapolis Museum of Art), [Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali], 05/04/1942 - 04/05/1942, cat. no. 3 1943, Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts, Exhibition of paintings by Salvador Dali, 15/03/1943 - 12/04/1943, no reference 1946, Boston, The Institute of Modern Art, Four Spaniards : Dali, Gris, Miro, Picasso, 24/01/1946 - 03/03/1946, cat. no. 1 1965, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, Salvador Dalí, 1910-1965, 18/12/1965 - 13/03/1966, cat. no. 18 1983, Barcelona, Palau Reial de Pedralbes, 400 obres de Salvador Dalí del 1914 al 1983, 10/06/1983 - 31/07/1983, cat.