Story of the Impunity and Facksimile Trials Cars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North Wales Car Club Ltd Will Promote a National B Permit Production Car Trial on Sunday 3Rd August 2003 at Hendrellwyn-Y

GERRY P EVANS MEMORIAL CYMRU TRIAL Run alongside the CYMRU BACH CLUBMANS TRIAL SATURDAY 20th JULY 2019 A qualifying round of the Link-Up Motorsport UK British PCT Championship, BTRDA® Car Trials & Allrounders Championships, ANWCC Trials & Allrounders Championships, WAMC Trials Championship and the Glynne Edwards Memorial Championship Welcome to the 57th Cymru Trial, again on the [5] All drivers in the event must produce a valid Hendrellwyn Farm site with its’ spectacular views Competition Licence, Club Membership Card and of the Snowdonia range, a big thanks to Mr Robin (where appropriate) Championship Registration Crossley for sponsoring the event by allowing us Card. Note that passengers, if carried (Motorsport the use of his land. UK GR T4.1), must also be in possession of a valid Club Membership Card (Motorsport UK GR As has been customary in recent years, we are T3.1.6). running as the first part of a Welsh Weekend, along with Clwyd Vale MC, for championship [6] The event is a qualifying round of the contenders and club competitors! following Championships – Motorsport UK British PCT Championship (2019/CT/0600), BTRDA® PCT We look forward to receiving your entry or, if not, Championship, BTRDA® Allrounders would welcome you to the event as a marshal or Championship (4/2019), ANWCC Trials official. Championship (23/2019), ANWCC Allrounders The Organising Team. Championship (24/2019), WAMC Trials Championship (58/2019) and the Glynne Edwards SUPPLEMENTARY REGULATIONS Memorial Championship (9/2019). [1] The North Wales Car Club Ltd will organize [7] The programme for the meeting will be: and promote a National B permit Production Car Scrutineering starts at 0900 hours. -

March/April 2007

IN THIS ISSUE • Portable Auto Storage .................... 6 • Reformulated Motor Oils ................. 5 • AGM Minutes .................................... 2 • Speedometer Cable Flick ................ 6 • At the Wheel ..................................... 2 • Speedometer Drive Repair ............. 7 • Austin-Healey Meet ......................... 3 • Tulip Rallye ....................................... 3 • Autojumble ..................................... 14 • Vehicle Importation Laws ............... 7 • Body Filler Troubles ........................ 6 • What Was I Thinking? ..................... 1 • Brits ‘Round the Parks AGM ......... 13 • World Record Garage Sale ............. 8 • Easidrivin’ ........................................ 1 • Your Rootes Are Showing .............. 6 • Executive Meeting ........................... 1 May 1 Meeting • High-Tech Meets No-Tech ............... 4 7:00 - Location TBA • MGs Gather ...................................... 9 May 18-20 AGM • MG Show Car Auction ..................... 4 • OECC 2007 Roster ........................ 11 Brits ‘Round the Parks • OECC/VCB Calendar ..................... 14 See Page __ For Details! • Oil in Classic Cars ........................... 3 Jun 5 Meeting • Oil is Killing Our Cars ...................... 5 7:00 - Location TBA OLD ENGLISH CAR CLUB OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, VANCOUVER COAST BRANCH MAR-APR 2007 - VOL 12, NUM 2 Easidrivin’ What Was I Alan Miles Thinking? The Smiths Easidrive automatic transmission was first introduced by Rootes Motors Or the Restoration of a in September 1959 in the UK and February 1960 in the U.S. It was offered as an option on the Series IIIA Hillman Minx and for the next three years on subsequent Minxes and Demon Sunbeam Imp - Part VI John Chapman Unfortunately I don't have much to report on the progress of the Imp restoration. Pat Jones has spent some 20-25 hours so far welding pieces of metal into the multitude of holes in the car created by the dreaded rust bug. After all these hours welding I can report that we have all the rear sub- frame replaced. -

The Alex Cameron Diecast and Toy Collection Wednesday 9Th May 2018 at 10:00 Viewing: Tuesday 8Th May 10:00-16:00 Morning of Auction from 9:00 Or by Appointment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Plant (Director) Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) The Alex Cameron Diecast and Toy Collection Wednesday 9th May 2018 at 10:00 Viewing: Tuesday 8th May 10:00-16:00 Morning of auction from 9:00 or by appointment Saleroom One 81 Greenham Business Park NEWBURY RG19 6HW Telephone: 01635 580595 Dave Kemp Bob Leggett Fax: 0871 714 6905 Fine Diecast Toys, Trains & Figures Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com Dominic Foster Toys Bid Here Without Being Here All you need is your computer and an internet connection and you can make real-time bids in real-world auctions at the-saleroom.com. You don’t have to be a computer whizz. All you have to do is visit www.the-saleroom.com and register to bid - its just like being in the auction room. A live audio feed means you hear the auctioneer at the same time as other bidders. You see the lots on your computer screen as they appear in the auction room, and the auctioneer is aware of your bids the moment you make them. Just register and click to bid! Order of Auction Lots Dinky Toys 1-38 Corgi Toys 39-53 Matchbox 54-75 Lone Star & D.C.M.T. 76-110 Other British Diecast 111-151 French Diecast 152-168 German Diecast 152-168 Italian Diecast 183-197 Japanese Diecast 198-208 North American Diecast 209-223 Other Diecast & Models 224-315 Hong Kong Plastics 316-362 British Plastics 363-390 French Plastics 391-460 American Plastics 461-476 Other Plastics 477-537 Tinplate & Other Toys 538-610 Lot 565 Buyers Premium: 17.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 21% of the Hammer Price Internet Buyers Premium: 20.5% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24.6% of the Hammer Price 2 www.specialauctionservices.com Courtesy of Daniel Celerin-Rouzeau and Model Collector magazine (L) and Diecast Collector magazine (R) Alex Cameron was born in Stirling and , with brother Ewen , lived his whole life in the beautiful Stirlingshire countryside, growing up in the picturesque cottage built by his father. -

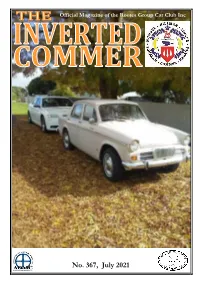

No. 367, July 2021

Official Magazine of the Rootes Group Car Club Inc No. 367, July 2021 ROOTES GROUP CAR CLUB INCORPORATED CONTACT US Address: P.O. Box 932 GLEN WAVERLEY, VIC 3150 Note that post box is only checked fortnightly – allow plenty of time for response Note new phone number: (03) 9005 0083 (AH) Email: [email protected] REG # A14412X Web Site: vic.rootesgroup.org.au MAIN OFFICE BEARERS 2020-21 PRESIDENT: Bernard Keating VICE PRESIDENT: Murray Brown 0422 550 449 (AH) (03) 5626 6340 (AH) [email protected] [email protected] SECRETARY: Thomas Clayton TREASURER: Bernie Meehan 0414 953 481 (AH) 0412 392 470 [email protected] [email protected] SOCIAL MEDIA OFFICER: Jodie Brown WEB SITE: Alex Chinnick (03) 5626 6340 (AH) [email protected] [email protected] SOCIAL COORDINATOR: Tim Christie MAGAZINE EDITOR: John Howell (03) 9741 6530 (AH) or 0409 966 942 0434 319 910 (AH) [email protected] [email protected] LIBRARIAN: Matthew Lambert REGALIA OFFICER: Kristi Lambert (03) 9570 5584 (After 8pm) (03) 9570 5584 (AH) [email protected] [email protected] SPARE PARTS OFFICER: Murray Brown CLUB PERMIT OFFICERS: (03) 5626 6340 (AH) Neil Yeomans: 0429 295 774 [email protected] Mick Lindsay: (03) 5860 8650 (AH) AOMC Reps: John Howell or 0417 304 616 Federation Reps: Neil Yeomans CLUB PERMITS For club permit applications & renewals, call one of the above Club Permit Officers who will tell you what needs to be done, and where to send your paperwork. Include a stamped envelope and don’t forget to sign the form! Fees: 1. -

Insider Dealing

Insider Dealing - “Family Impact” The brand new factory at Linwood near Glasgow took advantage of Government grants and was a long way from Rootes’ base in This year marks the 50th anniversary of a rear engined, sporty Coventry. This meant lengthy and costly logistics chains – the handling car with very advanced engineering. No... not the aluminium engine blocks were cast at Linwood, sent to Coventry Porsche 911 that’s festooning the covers of the anniversary for machining and back to Linwood for assembly. There was editions of car magazines right now, but the humbler Hillman Imp also reluctance from Rootes management to take an assignment which started production in May 1963. My family was connected in Scotland – the plant had 5 Managing Directors in 7 years. with the birth of this little car in Scotland, of which more later, The workers lacked the car making heritage of the Midlands, and the Imp undoubtedly influenced a young boy in short being largely ex-shipbuilders. trousers that the car industry was the life for me. Next to my Dad’s side valve 100E on the drive of our house, my uncle’s The combination of a new car, new factory, new workforce and factory fresh 1963 Imp looked like a technological marvel! changing management led to a difficult start for the Imp in terms of quality and profitability. The car was also not ready for production. Prior to launch, the Imp was subjected to thousands of miles of testing in temperature extremes from Kenya to Norway running prototypes night and day. The engineers identified some minor issues that needed improvement, but time pressures forced Rootes into holding the launch date – after all, no less than Prince Philip was booked for the opening ceremony. -

Davidson Shocked by Peugeot Pull-Out

classified advertising: 0208 267 5355 motorsport-news.co.uk January 25 2012 5 “Is Club Duratec the the voice of MOTORSPORT answer to ageing Kent?” ff1600 at a crossroads, p20 SIMON davidson shocked ARRON Davidson is now without a seat by peugeot pull-out British sportscar star Anthony ‘The potential Davidson has promised to continue chasing his dream of of race circuits winning the Le Mans 24 Hours, despite losing his race seat after Peugeot pulled the plug on its is great’ sportscar programme with immediate effect. The French automotive giant last week shocked the world of racing by announcing that it is withdrawing its successful 908 HDi Davidson (left) won Sebring with Peugeot machines from competition this year. Peugeot will not take part in this year’s Le Mans 24 Hours or in Hawkins Gary Photo: the FIA’s new World Endurance Championship. The French firm has cited both the ongoing European debt crisis and falling arron was wowed by rally action at Brands Hatch road car sales as concerns as the key reasons for its withdrawal. t might not have the cachet of, say, Ex-F1 racer Davidson, who has the 1964 Monte Carlo Rally, but a raced for Peugeot for the last two Le Mans will run dusty programme harbours fond seasons, finished fourth in last without 908s memories. The Ian Harwood Stages year’s 24 Hours with the team and was a Chester Motor Club event held was in contention to win the 2010 event before retiring with rumours over the winter that the events like Le Mans and Sebring. -

The Rootes Group: from Growth to Takeover

The Rootes Group: From Growth to takeover Begley, J., Donnelly, T. & Collis, C. Author post-print (accepted) deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Begley, J, Donnelly, T & Collis, C 2019, 'The Rootes Group: From Growth to takeover', Business History, vol. (In-press), pp. (In-press). https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2019.1598974 DOI 10.1080/00076791.2019.1598974 ISSN 0007-6791 ESSN 1743-7938 Publisher: Taylor and Francis This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Business History, on 23/08/2019, available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/00076791.2019.1598974 Copyright © and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This item cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. This document is the author’s post-print version, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer-review process. Some differences between the published version and this version may remain and you are advised to consult the published version if you wish to cite from it. The Rootes Group: from growth to take-over By Jason Begley, Clive Collis and Tom Donnelly Address: Centre for Business in Society, Faculty of Business, Jaguar Building Coventry University, Coventry, CV1 5FB. Tel +44 (0)2477 655783 Corresponding Author: Dr Jason Begley Email [email protected] Abstract This paper focusses on how a disparate group of firms was put together by the Rootes brothers in the late 1920s and early 1930s through a series of take-overs and mergers, catapulting the brothers from being simply car dealers to becoming major manufacturers in less than a decade. -

Newsletter Two

NEWSLETTER TWO. One of the strangest Circuit entries over the years! Adrian Boyd and Beatty Crawford in the Humber Super Snipe in 1964. They were well in the lead when they got stuck in a sheugh while reversing and lost 20 minutes - on the Sunday Run naturally. Just over six weeks now before we all gather in Killarney for the big party weekend. It’s an absolute sell out and we have had to close the books thanks to your fabulous response. A TASTER Here’s a sample of what’s in store, some of the people you will meet and the motors you will marvel at. Top of the bill are the seven former winning drivers and the ten winning co-drivers. You’ll see Paddy Hopkirk in his replica Mini Cooper S 33 EJB. Billy Coleman will be in John Mulholland’s fabulous Rothmans Porsche 911. Adrian Boyd will have his recently restored Renault Alpine out for the first time. And that's only the start. We have yet to finalise the entry but cop some of these names and cars! Graham Birrell from Scotland is a former international racing driver. Bill Blair from Doagh is bringing his 1963 Austin-Healey 3000 and Maurice Malcolm his 1967 example. Derek and Brian Boyd will be in a Lancia Delta Integrale as will Martin Buckley. Martin Boyle is another former racing ace. Then there’s Russell Brookes and John Brown, two of our star guests in the Andrews Heat for Hire Lotus Sunbeam on loan from John Leahey. Dan Brosnan, Peter Doughty, John O’Kane and Patsy Keenan are making the long trip from the States. -

Impost the Hillman Imp – Beware of Charlatans! Colin Valentine, Rufforth, Yorkshire

impost The Hillman Imp – Beware of Charlatans! Colin Valentine, Rufforth, Yorkshire The following article appeared in the newsletter of the North East England Classic & Pre-War Automobiles magazine, NECPWA News, 2017 No. 6. Unusually it has an article on the Imp. Written by Richard Mundell, it makes interesting reading… A car that gave me great pleasure was an Imp I owned in 1964. It was sad, therefore, to hear Imps rubbished in a recent TV programme, The Cars that made Britain Great. The programme was made, one might suppose, to celebrate British car design over the years. To do so, it followed the depressing custom of parading ‘celebrities’ along with experts. There was three of each. The celebrities consisted of a cricketer, a hill walker and a trendy poet. The journalistic experts, one pompous and two snide, were united in an apparently complete lack of personal experience of the Imp. Such experience was confined to the poet who had a mate who had one, and dismissed it twice as ‘crap’ because it was not a ‘babe magnet’. The general message was that the Imp was a small comical load of junk and the general impression was of ignorance. Given the blanket condemnation one wondered what the poor old Imp was doing in a programme about cars that made Britain great anyway. Rather more specific in their abuse are the several books that have been published on unconventional or unsuccessful cars. Knocking such motors forms a convenient refuge for the journalistic charlatan; they can pour scorn on them and get paid for it often without ever having driven them and without any appreciation of the engineering that has gone into them. -

Download Hillman Cars Free Ebook

HILLMAN CARS DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Malcolm Bobbitt | 64 pages | 30 Jul 2011 | Crecy Publishing | 9781908347015 | English | Appleby, United Kingdom Hillman Minx This history has been put together from other related websites and documentation, links to the websites are shown below. Only one of the strike committee members was Hillman Cars. A variety of manual transmissionswith column or floor change, and automatic transmissions were offered. The task Hillman Cars the brothers was that of turning failure into success - and they accepted Hillman Cars challenge. Categories : Hillman vehicles Rear-wheel-drive vehicles Cars introduced in s cars s cars s cars s cars Station wagons Sedans. In this way, we shall be able to Hillman Cars policy and expansion both in the UK and world markets and work together to one another's advantage. Hillman Minx Convertibles, and Projecsts for sale. Dawson has created a model of "11NR" with a 1. Hillman Minx Series V. Hillman Cars car was put out of the race by a crash, but it had made a splash. Some models were re-badged in certain markets, with the Sunbeam and Humber marques used for some exports. The shop stewards at the Acton factory Hillman Cars learned how to shout strike when a couple of newly weds at the factory, Hillman Cars were Hillman Cars shift workers, asked to be transferred to day shift. During the Hillman Cars company also produced a Hillman Cars five-seat model "14" with a 4-cylinder 2. At the beginning of the war, 17, employees were on the Rootes Hillman Cars. In"Minx" was the first British Hillman Cars car received a fully Hillman Cars four-speed gearbox. -

Rootes and Chrysler U.K. Passenger Cars

Rootes and Chrysler U.K. Passenger Cars New Chassis Number Format A new vehicle identification format was introduced in July 1970. New chassis plate example:- Chassis R G 211 000115 No. Service Paint H AA H 108 Code Code Trim Type 701 211 H 4 Code Code Breakdown of details shown in Chassis No. box:- 1st digit is the Plant Indicator (one letter) L = Linwood R = Ryton 2nd digit is the Series Year (one letter or figure) H = H Series G = G Series 3 = 3 Series Next 3 digits indicate Product Code (group of three numbers) IMP RANGE G SERIES H & 3 SERIES Hillman Imp Basic 423 423 Hillman Imp De-Luxe 413 413 Hillman Imp Super 443 443 Sunbeam Sport 593 593 Singer Chamois 543 - Sunbeam Stiletto 302 302 Hillman Husky 482 - Hillman Imp Van 463 - ARROW RANGE G SERIES EARLY H SERIES LATER H & 3 SERIES Hillman Minx 012 - - Hillman Minx Estate 082 - - Hillman Hunter 053 - - Hillman GT 041 - - Singer Vogue 353 - - Singer Vogue Estate 383 - - Hunter De-Luxe Saloon - 063 064 Hunter De-Luxe Estate - 085 160 Hunter Super - 074 075 Hunter GL Saloon - 058 059 Hunter GL Estate - 087 150 Hunter GLS - - 040 Hunter GT - 830 031 Humber Sceptre 112 112 090* Sunbeam Alpine 389 389 100 Sunbeam Rapier 342 342 190* Rapier H120 391 391 120 * On cars for France these numbers are replaced by L2S (Sceptre) and LSR (Rapier) for H Series and AAE (Sceptre) and AAD (Rapier) for 3 Series. AVENGER RANGE G SERIES H & 3 SERIES 3 SERIES Avenger Basic Saloon - 201 - Avenger De-Luxe Saloon 211 211 - (Export - Sunbeam 1250/1500) Avenger De-Luxe Estate - 280 - Avenger Super Saloon 221 221 - (Export - Sunbeam 1250/1500 De-Luxe) Avenger Super Estate - 283 - Avenger G.L. -

BTRDA Champions History Car Trials

BTRDA Championship Winners (Car Trials) Year PCT and CAR TRIALS Year Gold car Silver car Bronze car 1961 Mike Hinde Beetle 1961 1962 Mike Hinde Beetle 1962 1963 Mike Hinde 1963 1964 Mike Stephens DAF 55 1964 1965 Mike Hinde MG TF 1965 1966 Ken Hoare Beetle 1966 1967 Mike Hinde Mike Stephens 1967 1968 Brian Pickering Sumbean Imp Sport R Fitt 1968 1969 Gerry Evans Austin 1300 R White 1969 1970 Bill Moffatt Hillman Imp B Symes 1970 1971 Bill Moffatt Hillman Imp Mike Stephens 1971 1972 Bill Moffatt Hillman Imp Mike Harrison 1972 1973 Geoff Spencer Mini D Slater 1973 1974 Bill Moffatt Gineta G15 Brian Betteridge 1974 1975 Geoff Spencer Mini Malcolm Brown 1975 1976 Geoff Spencer Mini Dennis Wells ???? 1976 1977 Jim Loveday Panther Lima D Carr 1977 1978 Barrie Parker Peugeot 104 1978 1979 Ron Acres Steve Courts ???? 1979 1980 Barrie Parker Peugeot 104 Steve Courts 1980 1981 Steve Courts Skoda I Spencer ?????? 1981 1982 Graham Hoare Golf Mk 1 I Spencer 1982 1983 Mike Stephens Skoda D Hanley 1983 1984 Ken Hoare Golf Mk 1 C Harris ????? 1984 1985 Nick Pollitt Vauxhall Nova 1985 1986 Steve Courts Hillman Imp 1986 1987 Barrie Parker Peugeot 205 1987 1988 Steve Courts Hillman Imp 1988 1989 Mike Stephens VW Beetle 1989 1990 Neil Mackay Vauxhall Nova Swing 1990 1991 Mike Stephens VW Beetle 1302s 1991 1992 Barrie Parker Peugeot 205 Garry Preston 1992 1993 Neil Mackay Vauxhall Nova Swing C Richardson 1993 1994 Steve Courts Hillman Imp Graham Hoare Audi 80 Sport Cliff Morrell Hillman Imp 1994 1995 Steve Courts Hillman Imp Graham Hoare Audi 80 Sport Simon