This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LABOUR and TECHNOLOGY in the CAR INDUSTRY. Ford Strategies in Britain and Brazil

LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY. Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil Elizabeth Bortolaia Silva Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD, Imperial College of Science and Technology University of London May 1988 LABOUR AND TECHNOLOGY IN THE CAR INDUSTRY Ford strategies in Britain and Brazil ABSTRACT This thesis looks at aspects of recent changes in international competition in the car industry. It examines the implications of the changes for the relationship between technology and work and it considers how strategies of multinational corporations interact with different national contexts. It is based on a case-study of the Ford Motor Company in its two largest factories in Britain and Brazil, Dagenham and São Bernardo. Chapter 1 describes existing theoretical approaches to comparative studies of technology and work, criticizes technological and cultural determinist approaches and argues for a method that draws on a 'historical regulation' approach. Chapters 2, 3 and 4 describe the long-term background and recent shifts in the pattern of international competition in the motor industry. In particular they look at important shifts in the late 1970s and 1980s and at Ford's changes in management structure and product strategy designed to meet these challenges. Chapter 5 considers recent debates on international productivity comparisons and presents a fieldwork-based comparison of the production process at Dagenham and São Bernardo. The description shows the importance of issues other than technology in determining the flexibility and quality of production. In different national contexts, 2 different mixes of technology and labour can produce comparable results. Chapters 6, 7 and 8 look at the national and local contexts of industrial relations in the two countries to throw light on the different patterns of change observed in the factories. -

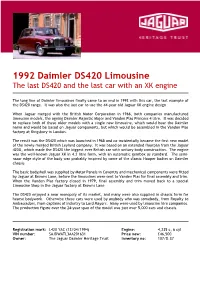

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine the Last DS420 and the Last Car with an XK Engine

1992 Daimler DS420 Limousine The last DS420 and the last car with an XK engine The long line of Daimler limousines finally came to an end in 1992 with this car, the last example of the DS420 range. It was also the last car to use the 44-year old Jaguar XK engine design When Jaguar merged with the British Motor Corporation in 1966, both companies manufactured limousine models, the ageing Daimler Majestic Major and Vanden Plas Princess 4 litre. It was decided to replace both of these older models with a single new limousine, which would bear the Daimler name and would be based on Jaguar components, but which would be assembled in the Vanden Plas factory at Kingsbury in London. The result was the DS420 which was launched in 1968 and co-incidentally became the first new model of the newly-merged British Leyland company. It was based on an extended floorpan from the Jaguar 420G, which made the DS420 the biggest ever British car with unitary body construction. The engine was the well-known Jaguar XK in 4.2 litre form, with an automatic gearbox as standard. The semi- razor edge style of the body was probably inspired by some of the classic Hooper bodies on Daimler chassis The basic bodyshell was supplied by Motor Panels in Coventry and mechanical components were fitted by Jaguar at Browns Lane, before the limousines were sent to Vanden Plas for final assembly and trim. When the Vanden Plas factory closed in 1979, final assembly and trim moved back to a special Limousine Shop in the Jaguar factory at Browns Lane The DS420 enjoyed a near monopoly of its market, and many were also supplied in chassis form for hearse bodywork. -

The North Wales Car Club Ltd Will Promote a National B Permit Production Car Trial on Sunday 3Rd August 2003 at Hendrellwyn-Y

GERRY P EVANS MEMORIAL CYMRU TRIAL Run alongside the CYMRU BACH CLUBMANS TRIAL SATURDAY 20th JULY 2019 A qualifying round of the Link-Up Motorsport UK British PCT Championship, BTRDA® Car Trials & Allrounders Championships, ANWCC Trials & Allrounders Championships, WAMC Trials Championship and the Glynne Edwards Memorial Championship Welcome to the 57th Cymru Trial, again on the [5] All drivers in the event must produce a valid Hendrellwyn Farm site with its’ spectacular views Competition Licence, Club Membership Card and of the Snowdonia range, a big thanks to Mr Robin (where appropriate) Championship Registration Crossley for sponsoring the event by allowing us Card. Note that passengers, if carried (Motorsport the use of his land. UK GR T4.1), must also be in possession of a valid Club Membership Card (Motorsport UK GR As has been customary in recent years, we are T3.1.6). running as the first part of a Welsh Weekend, along with Clwyd Vale MC, for championship [6] The event is a qualifying round of the contenders and club competitors! following Championships – Motorsport UK British PCT Championship (2019/CT/0600), BTRDA® PCT We look forward to receiving your entry or, if not, Championship, BTRDA® Allrounders would welcome you to the event as a marshal or Championship (4/2019), ANWCC Trials official. Championship (23/2019), ANWCC Allrounders The Organising Team. Championship (24/2019), WAMC Trials Championship (58/2019) and the Glynne Edwards SUPPLEMENTARY REGULATIONS Memorial Championship (9/2019). [1] The North Wales Car Club Ltd will organize [7] The programme for the meeting will be: and promote a National B permit Production Car Scrutineering starts at 0900 hours. -

Classic Vehicle Auctionauctionauction

Classic Vehicle AuctionAuctionAuction Friday 28th April 2017 Commencing at 11AM Being held at: South Western Vehicle Auctions Limited 61 Ringwood Road, Parkstone, Poole, Dorset, BH14 0RG Tel:+44(0)1202745466 swva.co.ukswva.co.ukswva.co.uk £5 CLASSIC VEHICLE AUCTIONS EXTRA TERMS & CONDITIONS NB:OUR GENERAL CONDITIONS OF SALE APPLY THE ESTIMATES DO NOT INCLUDE BUYERS PREMIUM COMMISSION – 6% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) BUYERS PREMIUM – 8% + VAT (Minimum £150 inc VAT) ONLINE AND TELEPHONE BIDS £10.00 + BUYERS PREMIUM + VAT ON PURCHASE 10% DEPOSIT, MINIMUM £500, PAYABLE ON THE FALL OF THE HAMMER AT THE CASH DESK. DEPOSITS CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD OR CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% Surcharge) BALANCES BY NOON ON THE FOLLOWING MONDAY. BALANCES CAN BE PAID BY DEBIT CARD, BANK TRANSFER, CASH (Which is subject to 1.25% surcharge), OR CREDIT CARD (Which is subject to 3.5% surcharge) ALL VEHICLES ARE SOLD AS SEEN PROSPECTIVE PURCHASERS ARE ADVISED TO SATISFY THEMSELVES AS TO THE ACCURACY OF ANY STATEMENT MADE, BE THEY STATEMENTS OF FACT OR OPINION. ALL MILEAGES ARE SOLD AS INCORRECT UNLESS OTHERWISE STATED CURRENT ENGINE AND CHASSIS NUMBERS ARE SUPPLIED BY HPI. ALL VEHICLES MUST BE COLLECTED WITHIN 3 WEEKS, AFTER 3 WEEKS STORAGE FEES WILL INCUR Lot 1 BENTLEY - 4257cc ~ 1949 LLG195 is the second Bentley (see lot 61) that the late Mr Wells started to make into a special in the 1990's. All the hard work has been done ie moving the engine back 18 inches, shortening the propshaft and making a new bulkhead, the aluminium special body is all there bar a few little bits which need finishing. -

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

P 01.Qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1

p 01.qxd 6/30/2005 2:00 PM Page 1 June 27, 2005 © 2005 Crain Communications GmbH. All rights reserved. €14.95; or equivalent 20052005 GlobalGlobal MarketMarket DataData BookBook Global Vehicle Production and Sales Regional Vehicle Production and Sales History and Forecast Regional Vehicle Production and Sales by Model Regional Assembly Plant Maps Top 100 Global Suppliers Contents Global vehicle production and sales...............................................4-8 2005 Western Europe production and sales..........................................10-18 North America production and sales..........................................19-29 Global Japan production and sales .............30-37 India production and sales ..............39-40 Korea production and sales .............39-40 China production and sales..............39-40 Market Australia production and sales..........................................39-40 Argentina production and sales.............45 Brazil production and sales ....................45 Data Book Top 100 global suppliers...................46-50 Mary Raetz Anne Wright Curtis Dorota Kowalski, Debi Domby Senior Statistician Global Market Data Book Editor Researchers [email protected] [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Paul McVeigh, News Editor e-mail: [email protected] Irina Heiligensetzer, Production/Sales Support Tel: (49) 8153 907503 CZECH REPUBLIC: Lyle Frink, Tel: (49) 8153 907521 Fax: (49) 8153 907425 e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (420) 606-486729 e-mail: [email protected] Georgia Bootiman, Production Editor e-mail: [email protected] USA: 1155 Gratiot Avenue, Detroit, MI 48207 Tel: (49) 8153 907511 SPAIN, PORTUGAL: Paulo Soares de Oliveira, Tony Merpi, Group Advertising Director e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (35) 1919-767-459 Larry Schlagheck, US Advertising Director www.automotivenewseurope.com Douglas A. Bolduc, Reporter e-mail: [email protected] Tel: (1) 313 446-6030 Fax: (1) 313 446-8030 Tel: (49) 8153 907504 Keith E. -

Motor Industry Facts 2015 Environment

UK AUTOMOTIVE AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: PROFILE MANUFACTURING REGISTRATIONS THE SOCIETY OF MOTOR VEHICLES ON MANUFACTURERS AND TRADERS THE ROAD MOTOR INDUSTRY FACTS 2015 ENVIRONMENT SAFETY AND SECURITY CONNECTED CARS UK AUTOMOTIVE WHAT IS SMMT? AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) is one of the largest INDUSTRY: and most influential trade associations operating in the UK. Its resources, PROFILE reputation and unrivalled automotive data place it at the heart of the UK automotive industry. It undertakes a variety of activities to support and represent the interests of the industry and has a long history MANUFACTURING of achievement. Working closely with member companies, SMMT acts as the voice of the UK motor industry, supporting and promoting its interests, at home and abroad, REGISTRATIONS to government, stakeholders and the media. VEHICLES ON SMMT represents over 600 automotive companies in the UK, providing them THE ROAD with a forum to voice their views on issues affecting the automotive sector, helping to guide strategies and build positive relationships with government and regulatory authorities. ENVIRONMENT To find out how to join SMMT and for more information, visit www.smmt.co.uk/memberservices SAFETY AND or e-mail [email protected]. SECURITY CONNECTED www.smmt.co.uk 02 CARS UK AUTOMOTIVE CONTENTS AT A GLANCE UK AUTOMOTIVE INDUSTRY: UK AUTOMOTIVE AT A GLANCE ...................................4-5 REGISTRATIONS ............................................................16 -

201502-Chrysler-Book-Stock.Pdf

C D E 1 Current as of February 24 2015 ***See Last page for Notes 2 Part Number Description Supplier 3 1940FAAD 1940 FARGO COE TRUCK AD MACLEANS APR 1941 CHRYSLER 4 WM3814 1942 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO PARTS BOOK CDN CHRYSLER 5 WM4281 1951-52 CHRYS/DOD/DESOTO/PLY PARTS BOOK CHRYSLER 6 C522 1952 CHRYSLER SALES BROCHURE CDN CHRYSLER 7 DS532 1953 DE SOTO FIREDOME 8 S/BRO CDN 12 PG CHRYSLER 8 PA1969 1956 PLYMOUTH S/BRO FOLD OUT 9 X 34" US CHRYSLER 9 1956SIPT 1956-62 SIMCA ARONDE PARTS CDN 284 PG c1962 CHRYSLER 10 WM4357 1957 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO SERVICE MANUAL SUPPLEMENT TO 55-56 MANUAL CHRYSLER 11 WM4393 1958 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO SERVICE MANUAL SUPPLEMENT TO 55-56 S/M WM-4335 CHRYSLER 12 WM4387 1958 DODGE OWNER'S MANUAL CDN CHRYSLER 13 P582 1958 PLYMOUTH S/BRO FOLD OUT 25 X 38" CDN CHRYSLER 14 PD16 1959 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO MOULDINGS CATALOG CDN CHRYSLER 15 WM4414 1959 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO SERVICE MANUAL SUPPLEMENT TO 55-56 S/M WM-4335 CHRYSLER 16 WM4480 1959 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO/IMP PARTS BOOK M SERIES CHRYSLER 17 D17247 1959 SIMCA ARONDE S/M 136 PG c1959 CHRYSLER 18 818703016 1959-63 SIMCA ARONDE S/M 154 PG c1963 CHRYSLER 19 WM4462 1960 CHR/PLY/DOD/DESOTO SERVICE MANUAL SUPPLEMENT TO 57-59 S/M WM-4430-31-32 CHRYSLER 20 57NY400 1960 CHRYSLER RADIO O/M AND PARTS LIST USA CHRYSLER 21 813700030 1960 DODGE TRUCK P SERIES S/M US CHRYSLER 22 WM4463 1960 DODGE, FARGO TRUCK S/M CDN SUPPLEMENT TO 57-59 S/M WM-4435-36-37 CHRYSLER 23 VA601 1960 'THE STORY OF VALIANT' S/B CDN CHRYSLER 24 CH601 1960 WINDSOR, SARATOGA, NEW YORKER S/B CDN CHRYSLER 25 WM4589 1960-63 VALIANT, -

March/April 2007

IN THIS ISSUE • Portable Auto Storage .................... 6 • Reformulated Motor Oils ................. 5 • AGM Minutes .................................... 2 • Speedometer Cable Flick ................ 6 • At the Wheel ..................................... 2 • Speedometer Drive Repair ............. 7 • Austin-Healey Meet ......................... 3 • Tulip Rallye ....................................... 3 • Autojumble ..................................... 14 • Vehicle Importation Laws ............... 7 • Body Filler Troubles ........................ 6 • What Was I Thinking? ..................... 1 • Brits ‘Round the Parks AGM ......... 13 • World Record Garage Sale ............. 8 • Easidrivin’ ........................................ 1 • Your Rootes Are Showing .............. 6 • Executive Meeting ........................... 1 May 1 Meeting • High-Tech Meets No-Tech ............... 4 7:00 - Location TBA • MGs Gather ...................................... 9 May 18-20 AGM • MG Show Car Auction ..................... 4 • OECC 2007 Roster ........................ 11 Brits ‘Round the Parks • OECC/VCB Calendar ..................... 14 See Page __ For Details! • Oil in Classic Cars ........................... 3 Jun 5 Meeting • Oil is Killing Our Cars ...................... 5 7:00 - Location TBA OLD ENGLISH CAR CLUB OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, VANCOUVER COAST BRANCH MAR-APR 2007 - VOL 12, NUM 2 Easidrivin’ What Was I Alan Miles Thinking? The Smiths Easidrive automatic transmission was first introduced by Rootes Motors Or the Restoration of a in September 1959 in the UK and February 1960 in the U.S. It was offered as an option on the Series IIIA Hillman Minx and for the next three years on subsequent Minxes and Demon Sunbeam Imp - Part VI John Chapman Unfortunately I don't have much to report on the progress of the Imp restoration. Pat Jones has spent some 20-25 hours so far welding pieces of metal into the multitude of holes in the car created by the dreaded rust bug. After all these hours welding I can report that we have all the rear sub- frame replaced. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Luton Motor Town

Contents Luton: Motor Town Luton: Motor Town 1910 - 2000 The resources in this pack focus on the major changes in the town during the 20th century. For the majority of the period Luton was a prosperous, optimistic town that encouraged forward-looking local planning and policy. The Straw Hat Boom Town, seeing problems ahead in its dependence on a single industry, worked hard to attract and develop new industries. In doing so it fuelled a growth that changed the town forever. However Luton became almost as dependant on the motor industry as it had been on the hat industry. The aim of this pack is to provide a core of resources that will help pupils studying local history at KS2 and 3 form a picture of Luton at this time. The primary evidence included in this pack may photocopied for educational use. If you wish to reproduce any part of this park for any other purpose then you should first contact Luton Museum Service for permission. Please remember these sheets are for educational use only. Normal copyright protection applies. Contents 1: Teachers’ Notes Suggestions for using these resources Bibliography 2: The Town and its buildings 20th Century Descriptions A collection of references to the town from a variety of sources. They illustrate how the town has been viewed by others during this period. Luton Council on Luton The following are quotes from the Year Book and Official Guides produced by Luton Council over the years. They offer an idea of how the Luton Council saw the town it was running. -

Notes to the Introduction I the Expansion of England

NOTES Abbreviations used in the notes: BDEE British Documents of the End of Empire Cab. Cabinet Office papers C.O. Commonwealth Office JICH journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History Notes to the Introduction 1. J. C. D. Clark, '"The Strange Death of British History?" Reflections on Anglo-American Scholarship', Historical journal, 40: 3 (1997), pp. 787-809 at pp. 803, 809. 2. S. R. Ashton and S. E. Stockwell (eds), British Documents of the End of Empire, series A, vol. I: Imperial Policy and Colonial Practice, 1925-1945, part I: Metro politan Reorganisation, Defence and International Relations, Political Change and Constitutional Reform (London: HMSO, 1996), p. xxxix. Some general state ments were collected, with statements on individual colonies, and submitted to Harold Macmillan, who dismissed them as 'scrappy, obscure and jejune, and totally unsuitable for publication' (ibid., pp. 169-70). 3. Clark,' "The Strange Death of British History"', p. 803. 4. Alfred Cobban, The Nation State and National Self-Determination (London: Fontana, 1969; first issued 1945 ), pp. 305-6. 5. Ibid., p. 306. 6. For a penetrating analysis of English constitutional thinking see William M. Johnston, Commemorations: The Cult of Anniversaries in Europe and the United States Today (New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers, 1991). 7. Elizabeth Mancke, 'Another British America: a Canadian Model for the Early Modern British Empire',]ICH, 25: 1 (January 1997), pp. 1-36, at p. 3. I The Expansion of England 1. R. A. Griffiths, 'This Royal Throne ofKings, this Scept'red Isle': The English Realm and Nation in the later Middle Ages (Swansea, 1983), pp.