The Rootes Group: from Growth to Takeover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 8/21 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

The North Wales Car Club Ltd Will Promote a National B Permit Production Car Trial on Sunday 3Rd August 2003 at Hendrellwyn-Y

GERRY P EVANS MEMORIAL CYMRU TRIAL Run alongside the CYMRU BACH CLUBMANS TRIAL SATURDAY 20th JULY 2019 A qualifying round of the Link-Up Motorsport UK British PCT Championship, BTRDA® Car Trials & Allrounders Championships, ANWCC Trials & Allrounders Championships, WAMC Trials Championship and the Glynne Edwards Memorial Championship Welcome to the 57th Cymru Trial, again on the [5] All drivers in the event must produce a valid Hendrellwyn Farm site with its’ spectacular views Competition Licence, Club Membership Card and of the Snowdonia range, a big thanks to Mr Robin (where appropriate) Championship Registration Crossley for sponsoring the event by allowing us Card. Note that passengers, if carried (Motorsport the use of his land. UK GR T4.1), must also be in possession of a valid Club Membership Card (Motorsport UK GR As has been customary in recent years, we are T3.1.6). running as the first part of a Welsh Weekend, along with Clwyd Vale MC, for championship [6] The event is a qualifying round of the contenders and club competitors! following Championships – Motorsport UK British PCT Championship (2019/CT/0600), BTRDA® PCT We look forward to receiving your entry or, if not, Championship, BTRDA® Allrounders would welcome you to the event as a marshal or Championship (4/2019), ANWCC Trials official. Championship (23/2019), ANWCC Allrounders The Organising Team. Championship (24/2019), WAMC Trials Championship (58/2019) and the Glynne Edwards SUPPLEMENTARY REGULATIONS Memorial Championship (9/2019). [1] The North Wales Car Club Ltd will organize [7] The programme for the meeting will be: and promote a National B permit Production Car Scrutineering starts at 0900 hours. -

INTRODUCTION the BMW Group Is a Manufacturer of Luxury Automobiles and Motorcycles

Marketing Activities Of BMW INTRODUCTION The BMW Group is a manufacturer of luxury automobiles and motorcycles. It has 24 production facilities spread over thirteen countries and the company‟s products are sold in more than 140 countries. BMW Group owns three brands namely BMW, MINI and Rolls- Royce. This project contains detailed information about the marketing and promotional activities of BMW. It contains the history of BMW, its evolution after the world war and its growth as one of the leading automobile brands. This project also contains the information about the growth of BMW as a brand in India and its awards and recognitions that it received in India and how it became the market leader. This project also contains the launch of the mini cooper showroom in India and also the information about the establishment of the first Aston martin showroom in India, both owned by infinity cars. It contains information about infinity cars as a BMW dealership and the success stories of the owners. Apart from this, information about the major events and activities are also mentioned in the project, the 3 series launch which was a major event has also been covered in the project. The two project reports that I had prepared for the company are also a part of this project, The referral program project which is an innovative marketing technique to get more customers is a part of this project and the other project report is about the competitor analysis which contains the marketing and promotional activities of the competitors of BMW like Audi, Mercedes and JLR About BMW BMW (Bavarian Motor Works) is a German automobile, motorcycle and engine manufacturing company founded in 1917. -

We Always Aim to Supply Transfers of the Highest Quality in Mint Condition

INTRODUCTION We hope you enjoy reading through our latest catalogue. We aim to provide restorers and historic vehicle enthusiasts with transfers and graphics to the highest attainable standard. Our background is mainly motor cycle orientated but over the years we have found that many motor cycle transfers were used on bicycles, and vice versa. If you are unable to find what you need always ask - we may be about to have the item printed. The majority of our stocks are the popular waterslide transfers but we also supply vinyl graphics where originally they were in that format. Low volume sellers are also supplied as vinyl graphics where a waterslide print run would be totally uneconomic. We use only best quality cast 10 year vinyl with a 'thinness' of 50 microns (2 thou inch). We are also able to offer white registration letters and numbers in four sizes, 1¾ inch and 2½ inch deep for motor cycles and 3 inch and 3½ inch for three wheelers and motor cars. See last page for further details. By far the majority of our artwork is produced by hand-drawing (as were the originals) and we resist the temptation to produce transfers using standard computer fonts, thus keeping the period look of the originals. We have tried to be as accurate as we can with the relevant location and year information in our listings, but your detailed knowledge of a particular model may well be greater than ours. LEGEND 4 Figure ref. nos. only - Waterslide Type 4 Figure ref. nos. suffixed by LC - Vinyl Graphics Best quality, 2 thou material V - Varnish Fix R.L.H. -

RESOLUTION INDEX Cont'd Resolution No. 63-5 the Board Has Designated the Scott Research Laboratories, Inc., As An- Authorized Control Testing Laboratory

- 4 - RESOLUTION INDEX Cont'd Resolution No. 63-5 The Board has designated the Scott Research Laboratories, Inc., as an- authorized control testing laboratory. Resolution No. 63-6 The Board approved the State-B.R. Higbie contract number 6137 for $2,46$'. Resolution No. 63-7 United Air Cleaner Division, Novo Industrial Corporation filed an application for certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control device on February 28, 1962. Resolution No. 63-8 Humber, Ltd. filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control device on October 29, 1962. Resolution No. 63-9 WHEREAS, every possible means must be used to effect a significant reduction in air pollution because of continued growth of Los Angeles and the State and, to give immediate 6 attention to the need for mass rapid transit in Los Angeles W County. Resolution No. 63-10 Fiat s.P.A. filed an application for a certificate of A approval for a crankcase emission control system on 1/22/63. W Resolution No. 63-11 Renault filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control system on 1/21/63. Resolution No. 63-12 Resolution exempting foreign cars from provisions of • Section 24390, Rover Motor Cars (England) Aston Martin (England) Lagonda (England). Resolution No. 63-13 Norris-Thermador filed an application for a certificate of approval for a crankcase emission control system on 2/19/63. Resolution No. 63-14 Resolution to exempt from Article 3 of this Chapter mo.tor driven cycles, implements of husbandry and•••••••••••••••· Reso_lution No. -

Samantha CARTER, Plaintiff, V. BENTLEY MOTORS INC. and F.C. Kerbeck Bentley, Defendants

Carter v. Bentley Motors Inc., --- F.Supp.3d ---- (2020) 2020 WL 5743042 Bentley salesperson she had witnessed discrimination against people of color inquiring about purchasing Bentleys, but 2020 WL 5743042 did not expect to be the subject of discrimination herself Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. when she later sought to purchase a Bentley. Plaintiff has United States District Court, D. New Jersey. alleged that she visited F.C. Kerbeck, a dealership located in Samantha CARTER, Plaintiff, Palmyra, New Jersey, on January 15, 2019 with intentions of purchasing a vehicle. Plaintiff alleges she had previously v. made an unsuccessful attempt to purchase a Bentley from a BENTLEY MOTORS INC. and different Bentley dealership named Bentley O'Gara.2 F.C. Kerbeck Bentley, Defendants. Plaintiff alleges she was greeted by an F.C. Kerbeck 1:19-cv-18035-NLH-JS salesperson named Brian McKnight.3 Plaintiff alleges that she | was told she could not test drive a vehicle without paying for it Signed 09/25/2020 first. According to Plaintiff, after questioning the salesperson and hearing from another F.C. Kerbeck employee that there Attorneys and Law Firms was no policy preventing her from test driving a car, she was SAMANTHA CARTER, 1001 S MAIN ST., SUITE 49, able to test drive an Aston Martin. KALISPELL, MT 59901, Plaintiff Pro se. Plaintiff alleges that she then gave F.C. Kerbeck a $100,000 GREGORY EDWARD REID, SILLS CUMMIS & GROSS deposit for a Bentley, using her phone to wire the money PC, ONE RIVERFRONT PLAZA, NEWARK, NJ 07102, to the dealership. -

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

March/April 2007

IN THIS ISSUE • Portable Auto Storage .................... 6 • Reformulated Motor Oils ................. 5 • AGM Minutes .................................... 2 • Speedometer Cable Flick ................ 6 • At the Wheel ..................................... 2 • Speedometer Drive Repair ............. 7 • Austin-Healey Meet ......................... 3 • Tulip Rallye ....................................... 3 • Autojumble ..................................... 14 • Vehicle Importation Laws ............... 7 • Body Filler Troubles ........................ 6 • What Was I Thinking? ..................... 1 • Brits ‘Round the Parks AGM ......... 13 • World Record Garage Sale ............. 8 • Easidrivin’ ........................................ 1 • Your Rootes Are Showing .............. 6 • Executive Meeting ........................... 1 May 1 Meeting • High-Tech Meets No-Tech ............... 4 7:00 - Location TBA • MGs Gather ...................................... 9 May 18-20 AGM • MG Show Car Auction ..................... 4 • OECC 2007 Roster ........................ 11 Brits ‘Round the Parks • OECC/VCB Calendar ..................... 14 See Page __ For Details! • Oil in Classic Cars ........................... 3 Jun 5 Meeting • Oil is Killing Our Cars ...................... 5 7:00 - Location TBA OLD ENGLISH CAR CLUB OF BRITISH COLUMBIA, VANCOUVER COAST BRANCH MAR-APR 2007 - VOL 12, NUM 2 Easidrivin’ What Was I Alan Miles Thinking? The Smiths Easidrive automatic transmission was first introduced by Rootes Motors Or the Restoration of a in September 1959 in the UK and February 1960 in the U.S. It was offered as an option on the Series IIIA Hillman Minx and for the next three years on subsequent Minxes and Demon Sunbeam Imp - Part VI John Chapman Unfortunately I don't have much to report on the progress of the Imp restoration. Pat Jones has spent some 20-25 hours so far welding pieces of metal into the multitude of holes in the car created by the dreaded rust bug. After all these hours welding I can report that we have all the rear sub- frame replaced. -

Pages for Preview

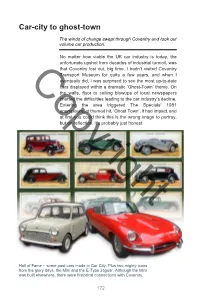

Car-city to ghost-town The winds of change swept through Coventry and took out volume car production. No matter how viable the UK car industry is today, the unfortunate upshot from decades of industrial turmoil, was that Coventry lost out, big time. I hadn’t visited Coventry Transport Museum for quite a few years, and when I eventually did, I was surprised to see the most up-to-date Copyrightcars displayed within a dramatic ‘Ghost-Town’ theme. On the walls, floor to ceiling blowups of local newspapers charted the difficulties leading to the car industry’s decline. Entering the area triggered The Specials’ 1981 unemployment themed hit, ‘Ghost Town’. It had impact, and at first you could think this is the wrong image to portray, but on reflection, it’s probably just honest. Hall of Fame – some past cars made in Car City. Plus two mighty icons from the glory days, the Mini and the E-Type Jaguar. Although the Mini was built elsewhere, there were historical connections with Coventry. 172 Copyright A year before the finish of car production, my father took part in the London to Brighton veteran car run driving a 1904 Siddeley which his department, Education and Training, maintained. As a postscript to car production ending, a special racing car had been built at Parkside for Tommy Sopwith junior – the son of the Hawker Siddeley owner. The 3.5 litre Sphinx was a massive departure from all that had gone My father in the before and was raced at Snetterton, Goodwood and 1904 Siddeley. Parked next to him Oulton Park, winning at the latter. -

Luton Motor Town

Contents Luton: Motor Town Luton: Motor Town 1910 - 2000 The resources in this pack focus on the major changes in the town during the 20th century. For the majority of the period Luton was a prosperous, optimistic town that encouraged forward-looking local planning and policy. The Straw Hat Boom Town, seeing problems ahead in its dependence on a single industry, worked hard to attract and develop new industries. In doing so it fuelled a growth that changed the town forever. However Luton became almost as dependant on the motor industry as it had been on the hat industry. The aim of this pack is to provide a core of resources that will help pupils studying local history at KS2 and 3 form a picture of Luton at this time. The primary evidence included in this pack may photocopied for educational use. If you wish to reproduce any part of this park for any other purpose then you should first contact Luton Museum Service for permission. Please remember these sheets are for educational use only. Normal copyright protection applies. Contents 1: Teachers’ Notes Suggestions for using these resources Bibliography 2: The Town and its buildings 20th Century Descriptions A collection of references to the town from a variety of sources. They illustrate how the town has been viewed by others during this period. Luton Council on Luton The following are quotes from the Year Book and Official Guides produced by Luton Council over the years. They offer an idea of how the Luton Council saw the town it was running. -

2008 Dodge Avenger Product Heritage

Contact: Brandt Rosenbusch 2008 Dodge Avenger Product Heritage The First Avenger Plans for the first car to carry the Avenger name were initiated by the Rootes Group (later to become Chrysler Europe) in England in 1963. Intended to replace Rootes’ best-selling vehicle of the time, the Hillman Minx, the project was delayed by funding issues; another car, the Arrow, would become the replacement for the Minx. Still, Rootes executives saw the need for a smaller car, and consideration of what they would call the “B-Car” began in earnest in November 1965. It would prove to be the first and last car developed by Rootes, following its 1967 takeover by Chrysler Corporation. Said to have drawn its inspiration from Detroit, the new car featured a readily identifiable “semi-fastback” design that would become its trademark. Much consideration was given to the needs of female customers; fashion consultants were employed during the design phase. The Hillman Avenger would feature a four-link rear suspension in place of traditional leaf springs, standard front anti-roll bars and a selection of four inline-four cylinder engines. The Hillman Avenger was introduced in February 1970 to popular acclaim. This B-class vehicle, built in sedan and wagon versions to compete with the Austin 1300, Ford Escort, Vauxhall Viva and other small cars, was designed to be the basic no-frills Hillman, with a four-speed manual gearbox an all-iron overhead valve engine. Four-door saloons were built first, followed by two-door saloons and five-door “estate” models. Many variations of the basic Avenger appeared over the years. -

British Car Dealerships in Victoria

British Car Dealerships In Victoria – ‘40’s, 50’s, 60’s, 70’s Victoria native Wayne Watkins presents an overview of who sold which English cars in Victoria during the period from the end of World War 2 until the late 1970s. MG Horwood Bros. took over Triumph and Standard In the late 1940’s, Victoria Super Service, at Vanguard from Louis Nelson in 1958 and then later Johnson and Blanshard, was just one dealership MG. My own ‘69 MGB was sold from Horwood Bros. in where a new MG could be bought. The garage 1969. They also sold Wolseley, Riley, Morris as well. backed out on to Pandora and was a past home of Bob Rebitt was the sales manager and he had a few DePape Motors. It is now the WIN store. The main tales to tell when I spoke to him recently. The cars front garage area was the past home of Romeo’s Pizza were shipped from England and eventually made on Johnson & Blanshard, but is now the Juliet their way to Ogden Point where they were dropped condominiums. I owned a ‘49 MG Y-Tourer that was off ‘dry’. That means no fluids. They were all towed to first bought by one of the young salesmen – they Horwood Bros. and topped up with oil and gasoline didn’t have demos in those days. That salesman was and electrolyte added to the Robin Yellowlees, who now batteries. As well as Rover, lives in Kelowna. That Morris was one of the Y-Tourer is now under marques sold by Horwood restoration by Ken Finnigan Bros.