What Do Aoes Do When They Are Deployed? Center for Naval Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress

Order Code RL32109 CRS Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress Updated April 21, 2005 Ronald O’Rourke Specialist in National Defense Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress Summary The Navy in FY2006 and future years wants to procure three new classes of surface combatants — a destroyer called the DD(X), a cruiser called the CG(X), and a smaller surface combatant called the Littoral Combat Ship (LCS). Congress in FY2005 funded the procurement of the first LCS and provided advance procurement funding for the first DD(X), which the Navy wants to procure in FY2007. The FY2006-FY2011 Future Years Defense Plan (FYDP) reduces planned DD(X) procurement to one per year in FY2007-FY2011 and accelerates procurement of the first CG(X) to FY2011. The FY2006 budget requests $666 million in advanced procurement funding for the first DD(X), which is planned for procurement in FY2007, $50 million in advance procurement funding for the second DD(X), which is planned for procurement in FY2008, and $1,115 million for DD(X)/CG(X) research and development. The budget requests $613.3 million for the LCS program, including $240.5 million in research and development funding to build the second LCS, $336.0 million in additional research and development funding, and $36.8 million in procurement funding for LCS mission modules. -

Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen?

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen? A Macroscopic Examination of the Trends in U.S. Naval Ship Costs Over the Past Several Decades Mark V. Arena • Irv Blickstein Obaid Younossi • Clifford A. Grammich Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

China's Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations

China’s Logistics Capabilities for Expeditionary Operations The modular transfer system between a Type 054A frigate and a COSCO container ship during China’s first military-civil UNREP. Source: “重大突破!民船为海军水面舰艇实施干货补给 [Breakthrough! Civil Ships Implement Dry Cargo Supply for Naval Surface Ships],” Guancha, November 15, 2019 Primary author: Chad Peltier Supporting analysts: Tate Nurkin and Sean O’Connor Disclaimer: This research report was prepared at the request of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to support its deliberations. Posting of the report to the Commission's website is intended to promote greater public understanding of the issues addressed by the Commission in its ongoing assessment of U.S.-China economic relations and their implications for U.S. security, as mandated by Public Law 106-398 and Public Law 113-291. However, it does not necessarily imply an endorsement by the Commission or any individual Commissioner of the views or conclusions expressed in this commissioned research report. 1 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Methodology, Scope, and Study Limitations ........................................................................................................ 6 1. China’s Expeditionary Operations -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs September 29, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33946 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Summary All of the Navy’s aircraft carriers, but none of its other surface ships, are nuclear-powered. Some Members of Congress, particularly on the House Armed Services Committee, have expressed interest in expanding the use of nuclear power to a wider array of Navy surface ships, starting with the CG(X), a planned new cruiser that the Navy had wanted to start procuring around FY2017. Section 1012 of the FY2008 Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4986/P.L. 110-181 of January 28, 2008) makes it U.S. policy to construct the major combatant ships of the Navy, including ships like the CG(X), with integrated nuclear power systems, unless the Secretary of Defense submits a notification to Congress that the inclusion of an integrated nuclear power system in a given class of ship is not in the national interest. The Navy studied nuclear power as a design option for the CG(X), but did not announce whether it would prefer to build the CG(X) as a nuclear-powered ship. The Navy’s FY2011 budget proposes canceling the CG(X) program and instead building an improved version of the conventionally powered Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class Aegis destroyer. The cancellation of the CG(X) program would appear to leave no near-term shipbuilding program opportunities for expanding the application of nuclear power to Navy surface ships other than aircraft carriers. -

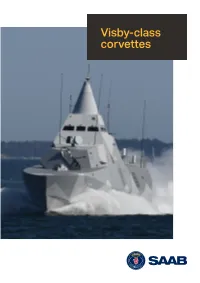

Visby-Class Corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES

Visby-class corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES Visby-class corvettes Virtually invisible in all signature bands, the innovative and powerful Visby-class corvettes from Saab continues to set the world benchmark for littoral fighting ships. Stealth, shallow draught, speed and fighting power makes Visby-class corvette a truly formidable surface combatant in the littoral arena. Visby-class corvette is a flexible surface combatant, designed for a wide range of roles: anti-surface warfare (ASuW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine countermeasures (MCM), patrol and much more. Gone are the days when the mere firepower of a ship was sufficient for its own protection. The concept today is action before – or even without – being detected. All-carbon fibre The all-composite carbon-fibre sandwich hull and superstructure allows the 650-ton Visby- class corvette the same payload capacity as that of a steel ship. At the same the carbon-fibre Visby-class corvette’s all-composite carbon- means that the Visby-class corvette has at least fibre hull and superstructure is not only lighter a 50% reduction in displacement compared with than steel, but also comparable for fire resistance a steel ship. and ballistic properties, and superior to steel for Resulting combat advantages are: higher speed vulnerability to blast and underwater explosions. for the same power as conventional metal ship of In terms of life cycle costs, the carbon-fibre com- the same dimensions, as well as greater manoeu- posite is entirely superior to steel and aluminium vrability and shallower draught – both important for fatigue. And the superior corrosion resistance tactical considerations in littoral waters. -

Deck Runoff NOD, Phase I Uniform National Discharge Standards For

This document is part of Appendix A, Deck Runoff: Nature of Discharge for the “Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS),” published in April 1999. The reference number is EPA-842-R-99-001. Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS) Appendix A Deck Runoff: Nature of Discharge April 1999 NATURE OF DISCHARGE REPORT Deck Runoff 1.0 INTRODUCTION The National Defense Authorization Act of 1996 amended Section 312 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA)) to require that the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) develop uniform national discharge standards (UNDS) for vessels of the Armed Forces for “...discharges, other than sewage, incidental to normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces, ...” [Section 312(n)(1)]. UNDS is being developed in three phases. The first phase (which this report supports), will determine which discharges will be required to be controlled by marine pollution control devices (MPCDs)—either equipment or management practices. The second phase will develop MPCD performance standards. The final phase will determine the design, construction, installation, and use of MPCDs. A nature of discharge (NOD) report has been prepared for each of the discharges that has been identified as a candidate for regulation under UNDS. The NOD reports were developed based on information obtained from the technical community within the Navy and other branches of the Armed Forces with vessels potentially subject to UNDS, from information available in existing technical reports and documentation, and, when required, from data obtained from discharge samples that were collected under the UNDS program. -

NAVY AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Cost-Effectiveness of Conventionally and Nuclear-Powered Carriers

United States General Accounting Office GAO Report to Congressional Requesters August 1998 NAVY AIRCRAFT CARRIERS Cost-Effectiveness of Conventionally and Nuclear-Powered Carriers GAO/NSIAD-98-1 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-259298 August 27, 1998 The Honorable Ted Stevens Chairman The Honorable Daniel K. Inouye Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on Defense Committee on Appropriations United States Senate The Honorable C.W. Bill Young Chairman The Honorable John P. Murtha Ranking Minority Member Subcommittee on National Security Committee on Appropriations House of Representatives The aircraft carrier forms the building block of the Navy’s forward deployed peacetime presence, crisis response, and war-fighting forces. The nuclear-powered carrier is the most expensive weapon system in the Nation’s arsenal and represents a significant portion of the Navy’s shipbuilding and conversion future years defense program. As requested, this report discusses the cost-effectiveness to the Navy of using conventionally and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers. As the Defense Department and the Navy assess design concepts for a new class of carriers, they will evaluate a number of factors, including different propulsion types. This report contains information and analysis that you may find useful in the process of allocating future defense resources. We are sending copies of this report to the Secretaries of Defense, Navy, Energy, and State and the Director, Office of Management and Budget. Copies will also be made available to others on request. Please contact me on (202) 512-3504 if you or your staff have any questions concerning this report. -

Optimization Models for Underway Replenishment of a Dispersed Carrier Battle Group

Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 1992-03 Optimization models for underway replenishment of a dispersed carrier battle group Wu, Tzu-li Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/30607 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey , California THESIS OPTIMIZATION MODELS FOR UNDERWAY REPLENISHMENT OF A DISPERSED CARRIER BA,TTLE GROUP by I Wu, Tzu-Li March 1992 Thesis Co-Advisor: Robert Dell Thesis Co-Advisor: Siriphong Lawphongpanich Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. Thesis + W9315 c!2 SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF THIS PAGE REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE la. REPORT SECURITY CLASSIFICATION 1b. RESTRICTIVE MARKINGS JNCLASSFIED 2a. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION AUTHORITY 3. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABlLlTYOF REPORT Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 2b. DECLASSIFICATION/DOWNGRADlNGSCHEDULE 4. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 5. MONITORING ORGANIZATION REPORT NUMBER(S) 6a NAME OF PERFORMING ORGANIZATION 6b OFFICE SYMBOL 7a. NAME OF MONITORING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School (If a~~licable) Naval Postgraduate School 55 6c. ADDRESS (City, State, and ZIP Code) 7b. ADDRESS (City, State, andZlPCode) Monterey, CA 93943-5000 Monterey, CA 93943-5000 8a. NAME OF FUNDING/SPONSORING 8b. OFFICE SYMBOL 9 PROCUREMENT INSTRUMENT IDENTIFICATION NUMBER ORGANIZATION (If applicable) I 8c ADDRESS (City, State, andZlP Code) 10 SOURCE OF FUNDING NUMBERS Program Element No Project No I I&.No Vvorl, Unn Access~ori Number 1 1 TITLE (Include Security Classification) OI'TIMIZATION MODELS FOR UNDERWAY REPLENISHMENT OF A DISPERSED CARRIER-BATTLE GROUP 12 PERSONAL AUTHOR(S) Wu, Tzu-1.i 13a TYPE OF REPORT 13b TIME COVERED 14 DATE OF REPORT (year, month, day) 15 PAGE COUNT Master's Thesls From lo 92 March 20 9 5 16. -

China's Global Navy—Today's Challenge for the United States And

Naval War College Review Volume 73 Number 4 Autumn 2020 Article 4 2020 China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and the U.S. Navy James E. Fanell U.S. Navy (Ret.) Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Fanell, James E. (2020) "China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and the U.S. Navy," Naval War College Review: Vol. 73 : No. 4 , Article 4. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol73/iss4/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fanell: China’s Global Navy—Today’s Challenge for the United States and t Captain James E. Fanell, USN (Ret.), concluded a career of nearly thirty years as a naval intelligence officer specializing in Indo-Pacific security affairs, with an emphasis on China’s navy and operations. He most recently served as the director of intelligence and information operations for the U.S. Pacific Fleet. He is a Government Fellow with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy and the creator and manager of the Indo-Pacific security forum Red Star Rising. Naval War College Review, Autumn 2020, Vol. 73, No. 4 Published by U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons, 2020 1 Naval War College Review, Vol. -

Cathodic Protection NOD, Phase I Uniform National Discharge

This document is part of Appendix A, Cathodic Protection: Nature of Discharge for the “Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS),” published in April 1999. The reference number is EPA-842-R-99-001. Phase I Final Rule and Technical Development Document of Uniform National Discharge Standards (UNDS) Appendix A Cathodic Protection: Nature of Discharge April 1999 NATURE OF DISCHARGE REPORT Cathodic Protection 1.0 INTRODUCTION The National Defense Authorization Act of 1996 amended Section 312 of the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (also known as the Clean Water Act (CWA)) to require that the Secretary of Defense and the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) develop uniform national discharge standards (UNDS) for vessels of the Armed Forces for “...discharges, other than sewage, incidental to normal operation of a vessel of the Armed Forces, ...” [Section 312(n)(1)]. UNDS is being developed in three phases. The first phase (which this report supports), will determine which discharges will be required to be controlled by marine pollution control devices (MPCDs)—either equipment or management practices. The second phase will develop MPCD performance standards. The final phase will determine the design, construction, installation, and use of MPCDs. A nature of discharge (NOD) report has been prepared for each of the discharges that has been identified as a candidate for regulation under UNDS. The NOD reports were developed based on information obtained from the technical community within the Navy and other branches of the Armed Forces with vessels potentially subject to UNDS, from information available in existing technical reports and documentation, and, when required, from data obtained from discharge samples that were collected under the UNDS program.