Navy DD(X), CG(X), and LCS Ship Acquisition Programs: Oversight Issues and Options for Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs December 23, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32109 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy DDG-51 and DDG-1000 Destroyer Programs: Background and Issues for Congress Summary Consistent with a proposal announced by the Navy in July 2008, the Administration’s FY2010 defense budget proposed ending procurement of DDG-1000 (Zumwalt) class destroyers with the third ship, which was authorized and partially funded in FY2009, and restarting procurement DDG-51 (Arleigh Burke) class Aegis destroyers, which were last procured in FY2005. The proposed FY2010 defense budget requested procurement funding to complete the cost of the third DDG-1000 and to procure one DDG-51, and advance procurement funding for two more DDG- 51s that the Navy wants to procure in FY2011. The Navy’s plans for destroyer procurement in FY2012 and beyond have been unclear. The Navy since July 2008 has spoken on several occasions about a desire to build a total of 11 or 12 DDG- 51s between FY2010 and FY2015, but the Navy also testified to the Seapower subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee on June 16, 2009, that it is conducting a study on destroyer procurement options for FY2012 and beyond that is examining design options based on either the DDG-51 or DDG-1000 hull form. A January 2009 memorandum from the Department of Defense acquisition executive called for such a study. A November 2009 press report stated that the study was begun in late Spring 2009, that it was nearing completion, that it examined options for equipping the DDG-51 and DDG-1000 designs with an improved radar, and that preliminary findings from the study began to be briefed to “key parties on Capitol Hill and in industry” in October 2009. -

Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen?

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Why Has the Cost of Navy Ships Risen? A Macroscopic Examination of the Trends in U.S. Naval Ship Costs Over the Past Several Decades Mark V. Arena • Irv Blickstein Obaid Younossi • Clifford A. Grammich Prepared for the United States Navy Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Navy. -

2019 Annual Report $2B

2019 ANNUAL REPORT HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES INGALLS INDUSTRIES HUNTINGTON 2019 annual RE P ort $2B HII HAS INVESTED NEARLY $2 BILLION IN CAPITAL EXPENDITURES OVER THE PAST FIVE YEARS AT ITS INGALLS AND NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING FACILITIES TO IMPROVE EFFICIENCIES AND AFFORDABILITY ACROSS THE ENTERPRISE. Ingalls Shipbuilding, in Pascagoula, Mississippi, is the largest supplier of U.S. Navy surface combatants. HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES Huntington Ingalls Industries is America’s largest military shipbuilding company and a provider of professional services to partners in government and industry. For more than a century, HII’s Newport News and Ingalls shipbuilding divisions in Virginia and Mississippi have built more ships in more ship classes than any other U.S. naval shipbuilder. HII’s Technical Solutions division supports national security missions around the globe with unmanned systems, defense and federal solutions, nuclear and environmental services, and fleet sustainment. Headquartered in Newport News, Virginia, HII employs more than 42,000 people operating both domestically and internationally. Cover Image: Newport News Shipbuilding delivered USS Delaware (SSN 791) to the U.S. Navy in 2019. FINANCIAL OPERATING RESULTS ($ in millions, except per share amounts) 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 Sales and Service Revenues $ 8,899 $ 8,176 $ 7,441 $ 7,068 $ 7,020 Operating Income 736 951 881 876 774 Operating Margin 8.3 % 11.6 % 11.8 % 12.4 % 11.0 % (1) Adjusted Segment Operating Income 660 663 688 715 769 Adjusted Segment Operating Margin (1) 7.4 % 8.1 % 9.2 % 10.1 % 11.0 % Diluted EPS 13.26 19.09 10.46 12.14 8.36 (2) Adjusted Diluted EPS 14.01 19.09 12.14 12.14 10.55 Net Cash Provided by Operating Activities 896 914 814 822 861 (1)Adjusted Segment Operating Income and Adjusted Segment Operating Margin are non-GAAP financial measures that exclude the operating FAS/CAS adjustment, non-current state income taxes, goodwill impairment charges and purchased intangibles impairment charges. -

January 2013 Newsletter.Pub

US Coast Guard Auxiliary Newsletter, South Lake Tahoe, Flotilla 11N -11-04 DIRECTIONDIRECTION FINDER FINDER Newsletter date: January 2013 Volume XLVII, Issue 1 Inside this Issue: Page Happy New year 1 FLOT 11 04 Officers 2 Battleship IOWA 3 IOWA 4,5 IOWA 6 IOWA 7 Trivia Answer 8 Odds and Ends 9 The DIRECTION FINDER is published by the US Coast Guard Auxiliary, South Lake Tahoe CA. Flotilla 11-04. Submission of articles or sub- jects of interest, including pho- tographs are welcomed and encouraged. The editor reserves the right to make changes without altering the intended content. All sub- missions should be directed to the editor: Victor Beelik Po box 10514 Zephyr Cove, NV 89448 WE WISH YOU A HAPPY Email: [email protected] NEW YEAR! The information contained in this publication is subject to The provisions of the Privacy Act of 1974, and may be used only for the official business of the Coast Guard or the Coast Guard Auxiliary. Page 2 DIRECTION FINDER FLOTILLA 11-04 OFFICERS (YEAR 2013) Flotilla Commander Jim Snell [email protected] Vice Flotilla Commander Stuart Harrington [email protected] FSO-NS (Navigation Systems) Bruce Cole [email protected] FSO-CM (Communications) Vic Beelik [email protected] FSO-FN (Finance) Bruce Cole [email protected] FSO–CS (Communication Serv.) Jim Snell [email protected] FSO-MA (Materials) Jim Snell [email protected] FSO-VE (Vessel Examiner) Vic Beelik [email protected] FSO-PB (Publications) Vic Beelik [email protected] FSO-MT (Member Training) Stu Harrington [email protected] FSO-PE (Public -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

The Cost of the Navy's New Frigate

OCTOBER 2020 The Cost of the Navy’s New Frigate On April 30, 2020, the Navy awarded Fincantieri Several factors support the Navy’s estimate: Marinette Marine a contract to build the Navy’s new sur- face combatant, a guided missile frigate long designated • The FFG(X) is based on a design that has been in as FFG(X).1 The contract guarantees that Fincantieri will production for many years. build the lead ship (the first ship designed for a class) and gives the Navy options to build as many as nine addi- • Little if any new technology is being developed for it. tional ships. In this report, the Congressional Budget Office examines the potential costs if the Navy exercises • The contractor is an experienced builder of small all of those options. surface combatants. • CBO estimates the cost of the 10 FFG(X) ships • An independent estimate within the Department of would be $12.3 billion in 2020 (inflation-adjusted) Defense (DoD) was lower than the Navy’s estimate. dollars, about $1.2 billion per ship, on the basis of its own weight-based cost model. That amount is Other factors suggest the Navy’s estimate is too low: 40 percent more than the Navy’s estimate. • The costs of all surface combatants since 1970, as • The Navy estimates that the 10 ships would measured per thousand tons, were higher. cost $8.7 billion in 2020 dollars, an average of $870 million per ship. • Historically the Navy has almost always underestimated the cost of the lead ship, and a more • If the Navy’s estimate turns out to be accurate, expensive lead ship generally results in higher costs the FFG(X) would be the least expensive surface for the follow-on ships. -

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress

Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Ronald O'Rourke Specialist in Naval Affairs September 29, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL33946 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Navy Nuclear-Powered Surface Ships: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress Summary All of the Navy’s aircraft carriers, but none of its other surface ships, are nuclear-powered. Some Members of Congress, particularly on the House Armed Services Committee, have expressed interest in expanding the use of nuclear power to a wider array of Navy surface ships, starting with the CG(X), a planned new cruiser that the Navy had wanted to start procuring around FY2017. Section 1012 of the FY2008 Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 4986/P.L. 110-181 of January 28, 2008) makes it U.S. policy to construct the major combatant ships of the Navy, including ships like the CG(X), with integrated nuclear power systems, unless the Secretary of Defense submits a notification to Congress that the inclusion of an integrated nuclear power system in a given class of ship is not in the national interest. The Navy studied nuclear power as a design option for the CG(X), but did not announce whether it would prefer to build the CG(X) as a nuclear-powered ship. The Navy’s FY2011 budget proposes canceling the CG(X) program and instead building an improved version of the conventionally powered Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class Aegis destroyer. The cancellation of the CG(X) program would appear to leave no near-term shipbuilding program opportunities for expanding the application of nuclear power to Navy surface ships other than aircraft carriers. -

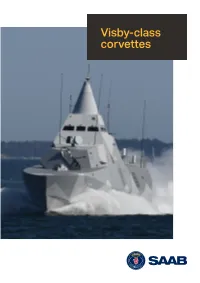

Visby-Class Corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES

Visby-class corvettes VISBY-CLASS CORVETTES Visby-class corvettes Virtually invisible in all signature bands, the innovative and powerful Visby-class corvettes from Saab continues to set the world benchmark for littoral fighting ships. Stealth, shallow draught, speed and fighting power makes Visby-class corvette a truly formidable surface combatant in the littoral arena. Visby-class corvette is a flexible surface combatant, designed for a wide range of roles: anti-surface warfare (ASuW), anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine countermeasures (MCM), patrol and much more. Gone are the days when the mere firepower of a ship was sufficient for its own protection. The concept today is action before – or even without – being detected. All-carbon fibre The all-composite carbon-fibre sandwich hull and superstructure allows the 650-ton Visby- class corvette the same payload capacity as that of a steel ship. At the same the carbon-fibre Visby-class corvette’s all-composite carbon- means that the Visby-class corvette has at least fibre hull and superstructure is not only lighter a 50% reduction in displacement compared with than steel, but also comparable for fire resistance a steel ship. and ballistic properties, and superior to steel for Resulting combat advantages are: higher speed vulnerability to blast and underwater explosions. for the same power as conventional metal ship of In terms of life cycle costs, the carbon-fibre com- the same dimensions, as well as greater manoeu- posite is entirely superior to steel and aluminium vrability and shallower draught – both important for fatigue. And the superior corrosion resistance tactical considerations in littoral waters. -

Wilfred Sykes Education Corporation

Number 302 • summer 2017 PowerT HE M AGAZINE OF E NGINE -P OWERED V ESSELS FRO M T HEShips S T EA M SHI P H IS T ORICAL S OCIE T Y OF A M ERICA ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Messageries Maritimes’ three musketeers 8 Sailing British India An American Classic: to the Persian steamer Gulf 16 Post-war American WILFRED Freighters 28 End of an Era 50 SYKES 36 Thanks to All Who Continue to Support SSHSA July 2016-July 2017 Fleet Admiral – $50,000+ Admiral – $25,000+ Maritime Heritage Grant Program The Dibner Charitable The Family of Helen & Henry Posner, Jr. Trust of Massachusetts The Estate of Mr. Donald Stoltenberg Ambassador – $10,000+ Benefactor ($5,000+) Mr. Thomas C. Ragan Mr. Richard Rabbett Leader ($1,000+) Mr. Douglas Bryan Mr. Don Leavitt Mr. and Mrs. James Shuttleworth CAPT John Cox Mr. H.F. Lenfest Mr. Donn Spear Amica Companies Foundation Mr. Barry Eager Mr. Ralph McCrea Mr. Andy Tyska Mr. Charles Andrews J. Aron Charitable Foundation CAPT and Mrs. James McNamara Mr. Joseph White Mr. Jason Arabian Mr. and Mrs. Christopher Kolb CAPT and Mrs. Roland Parent Mr. Peregrine White Mr. James Berwind Mr. Nicholas Langhart CAPT Dave Pickering Exxon Mobil Foundation CAPT Leif Lindstrom Peabody Essex Museum Sponsor ($250+) Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ferguson Mr. and Mrs. Jeffrey Lockhart Mr. Henry Posner III Mr. Ronald Amos Mr. Henry Fuller Jr. Mr. Jeff MacKlin Mr. Dwight Quella Mr. Daniel Blanchard Mr. Walter Giger Jr. Mr. and Mrs. Jack Madden Council of American Maritime Museums Mrs. Kathleen Brekenfeld Mr. -

Norfolk's Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64

Norfolk’s Nauticus: USS Wisconsin BB‐64 The history of the U.S. Navy’s use of battleships is quite interesting. Some say the first battleship was the USS Monitor, used against the CSS Virginia (Monitor) in Hampton Roads in 1862. Others say it was the USS Michigan, commissioned in 1844. It was the first iron‐ hulled warship for the defense of Lake Erie. In any case, battleships, or as some have nicknamed them “Rolling Thunder,” have made the United States the ruler of the high seas for over one century. A history of those famous ships can be found in the source using the term bbhistory. By the way, BB‐64 stands for the category battleship and the number assigned. This photo program deals with the USS Wisconsin, which is moored in Norfolk and part of the Hampton Road Naval Museum and Nauticus. Though the ship has been decommissioned, it can be recalled into duty, if necessary. On July 6, 1939, the US Congress authorized the construction of the USS Wisconsin. It was built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Its keel was laid in 1941, launched in 1943 and commissioned on April 15, 1944. The USS Wisconsin displaces 52,000 tons at full load, length 880 fee, beam 108 feet and draft at 36 feet. The artillery includes 16‐inch guns that fire shells weighing one‐ton apiece. Other weapons include antiaircraft guns and later added on missile launchers. The ship can reach a speed of 30 nautical miles (knots) per hour or 34 miles mph. The USS Wisconsin’s first battle star came at Leyte Operation, Luzon attacks in the Pacific in December 1944. -

United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana

Case 2:20-cv-01002-BWA-JVM Document 22 Filed 05/14/20 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA ROBERT BOURGEOIS II CIVIL ACTION VERSUS NO. 20-1002 HUNTINGTON INGALLS SECTION M (1) INC., ET AL. ORDER & REASONS Before the Court is a motion by plaintiff Robert Bourgeois II to remand this matter to the Civil District Court for the Parish of Orleans, State of Louisiana (“CDC”).1 Defendants Huntington Ingalls Inc.2 and Albert L. Bossier, Jr.3 (collectively, “Avondale”) respond in opposition,4 and Bourgeois replies in further support of his motion.5 Considering the parties’ memoranda, the record, and the applicable law, the Court denies the motion to remand. I. BACKGROUND This is a toxic tort case related to asbestos exposure. In February 2019, Bourgeois was diagnosed with malignant pleural mesothelioma.6 On April 1, 2019, Bourgeois filed this action in the CDC alleging that his cancer was caused by exposure to asbestos.7 In addition to Avondale, Bourgeois names as defendants Travelers Indemnity Company,8 Conagra Grocery 1 R. Doc. 11. 2 Huntington Ingalls Inc. has had several past names including Northrop Grumman Ship Systems, Inc., Avondale Industries, Inc., Avondale Shipyards, Inc., and Avondale Marine Ways, Inc. 3 Bossier was an executive officer of Huntington Ingalls. R. Doc. 1-2 at 1. 4 R. Doc. 17. 5 R. Doc. 21. 6 R. Doc. 1-2 at 2. 7 Id. at 1-2. 8 Travelers is alleged to be the insurer of three former Avondale executive officers. R. Doc. 1-5 at 1. -

What Do Aoes Do When They Are Deployed? Center for Naval Analyses

CAB D0000255.A1 / Final May 2000 What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? Burnham C. McCaffree, Jr. • Jay C. Poret Center for Naval Analyses 4401 Ford Avenue • Alexandria, Virginia 22302-1498 Copyright CNA Corporation/Scanned October 2002 Approved for distribution: May 2000 ,*&. KW^f s£^ ••—H. Dwight Lydtis, Jr.rDfffector USMC & Expeditionary Systems Team Acquisition, Technology & Systems Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION UNLIMITED For copies of this document, call the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section (703) 824-2130 Copyright © 2000 The CNA Corporation What Do AOEs Do When They Are Deployed? The Navy has twelve aircraft carriers and eight fast combat support ships (AOEs) that were built to act as carrier battle group (CVBG) station ships. The multi-product AOE serves as a "warehouse" for fuel, ammunition, spare parts, provisions, and stores to other CVBG ships, especially the carrier. Currently, an AOE deploys with about four out of every five CVBGs on peacetime forward deployments. Prior to 1996, when there were only four AOEs, only two of every five CVBGs deployed with an AOE. That frequency could resume in the latter part of this decade when AOE-1 class ships are retired at the end of their 35-year service life. The combat logistics force (CLF) that supports forward deployed combatant ships consists of CVBG station ships and shuttle ships (oilers, ammunition ships, and combat stores ships) that resupply the station ships and the combatants as well.