Chapters 5C—Transit and Non-Motorized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7.2 Transit Lines

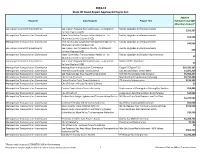

User Guide and Model Documentation for SACSIM19 – June 2020 Transit Lines The major fixed route transit services in the SACOG region are explicitly represented in the transit networks as “lines”, or series of stops served by a transit vehicle at a specified service frequency. Table 7-1 provides a listing of the operators included. Each line operating on a fixed (or largely fixed) route, and with a published schedule, is coded into the SACSIM transit networks. 7.2.1 Transit Service Periods SACSIM fixed-route transit considers five different service periods: • Period 1, spanning from 5:00am until 9:00am • Period 2, from 9:00am until 3:00pm • Period 3, from 3:00pm until 6:00pm • Period 4, from 6:00pm until 8:00pm • Period 5, from 8:00pm until 11:00pm By breaking up transit service into these periods, SACSIM aims to accurately represent how transit service varies throughout the day, e.g.: • Transit availability and frequency differences throughout the day • How transit is affected by changes in highway traffic congestion throughout the day 7.2.2 Transit Line Attributes Table 7-2 provides a listing of the key variables coded for each transit line. • The NAME of the line. o For lines existing in the base year, the first 4 characters refer to the operator name: . AMTR – Amtrak Capitol Corridor service . AUBT – Auburn Transit . CSUS – California State University Sacramento Hornet Shuttle . ELDO – El Dorado Transit . ETRN – E-Tran, in Elk Grove . FOLS – Folsom Stage Line . PLAC – Placer County Transit . RSVL – Roseville Transit . SCTL – South County Link (serving south Sacramento County) . -

Copy of LCTOP 14-15 Cycle 2 Final Projects.Xlsx

LCTOP ITEM I J Fiscal Year 2014-15 Cycle 2 Project List Disadvantaged Community (DAC) Ref. Project title Project Description Project Lead Total benefit? Reduce Fare Project for Mendocino College This funding will be used to subsidize the bus fares for 1 Students Mendocino College students. No DAC Mendocino Transit Authority $ 31,142 No Expansion of express Expand express route transit services provided by Redding 2 services Area Bus Authority. No DAC Shasta Regional Transportation Agency $ 62,657 No To install 27 shelters throughout the regional transit Tehama County Transportation 3 Bus Shelter Install service area. Commission $ 20,762 Yes Provide means of information (signage, info boxes, Increase Awareness of displays) at bus stops, social services, senior agencies, 4 Transit System connection locations. No DAC Trinity County - Transit $ 4,618 No To upgrade an existing transit stop to include a bus shelter Auburn Transit- Municipal within the newly expanded airport route in order to Airport Route - Earhart & increase active transportation and encourage ridership. 5 Rickenbacker Bus Shelter No DAC City of Auburn $ 3,782 No City of Davis/Unitrans Weekend Service To increase service (extend transit routes, increase 6 Expansion frequency of service, extend service hours). No DAC City of Davis/Unitrans $ 30,977 No E-tran Local Route 156 Improve headways from 30 minutes to 15 minutes to Transit Service Frequency complement Sacramento RT's New Blue Line Light Rail 7 Improvements Service. City of Elk Grove $ 59,300 Yes Louis Orlando Transfer Reconstruction of the Louis Orlando Transfer Point will Point Improvements and allow for transit service expansion, enhancement and Fixed Route Service upgrades to encourage ridership, mode sharing and to 8 Enhancements support and encourage active transportation. -

FY 2018-19 SGR Project List

2018-19 State Of Good Repair Approved Project List 2018-19 Recipient Sub-Recipient Project Title Estimated total SGR Allocation Amount* San Joaquin Council of Governments San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission - to Altamont Facility Upgrades and Improvements $256,937 Corridor Express (ACE) Metropolitan Transportation Commission Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority - to Facility Upgrades and Improvements $31,362 Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) Metropolitan Transportation Commission Alameda County Congestion Management Agency - to Facility Upgrades and Improvements $40,599 Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) San Joaquin Council of Governments San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority - to Altamont Facility Upgrades and Improvements $44 Corridor Express (ACE) Metropolitan Transportation Commission Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority - to Facility Upgrades and Capital Improvements $0 Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) San Joaquin Council of Governments San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission - to Altamont Railcar Midlife Overhaul $0 Corridor Express (ACE) Metropolitan Transportation Commission Metropolitan Transportation Commission Clipper®/Clipper® 2.0 $10,250,287 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District East Bay Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) $3,053,265 Metropolitan Transportation Commission San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District STA SGR Preventative Maintenance $5,980,007 Metropolitan Transportation Commission City of San Francisco Muni Facility Rehabilitation Campaign $9,794,303 Metropolitan Transportation -

Transportation

Chapter 16—Transportation 16.1 Introduction This chapter describes the existing conditions (environmental and regulatory) and assesses the potential transportation impacts of the 2020 Metropolitan Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy (proposed MTP/SCS). Where necessary and feasible, mitigation measures are identified to reduce these impacts. The information presented in this chapter is based on review of existing information and is regional in scope. Data, analysis, and findings provided in this chapter were considered and prepared at a programmatic level. In response to the Notice of Preparation (NOP), SACOG received several comments related to transportation from Sierra Club (Placer County), Sacramento Metropolitan Air Quality Management District (SMAQMD), ECOS, Sierra Club (Placer County), and Delta Protection Commission. The commenters expressed that the Draft EIR should consider the following: . Different transportation improvements for Placer County, . Relationship between planned transportation improvements and the goals of the MTP/SCS, . Increased transit service, . Induced vehicle miles traveled, . Multiple lanes as a part of consideration of managed lanes, . Increased funding for active transportation projects, . Shared modeling with member jurisdictions, . Relationship between vehicle miles traveled (VMT) and greenhouse gases (GHG), . Equity and environmental justice concerns related to transit access, . VMT impacts, and . Delta Trail Master Plan. The CEQA Guidelines note that comments received during the NOP scoping process can be helpful in “identifying the range of actions, alternatives, mitigation measures, and significant effects to be analyzed in depth in an EIR and in eliminating from detailed study issues found not to be important.” (CEQA Guidelines Section 15083.) Neither the CEQA Guidelines nor Statutes require a lead agency to respond directly to comments received in response to the NOP, but they do require they be considered. -

FY 2012 Short Range Transit Plan: FY 2012-2022

Attachment 1 DRAFT Short Range Transit Plan: FY 2011 FY Plan: Transit Range Short FY 2012 – FY 2022 - 2021 November 2012 Short Range Transit Plan: FY 2012-2022 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ----------------------------------------------------4 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND VISION------------------------------------------------------5 2.0 OVERVIEW OF THE DISTRICT AND THE TRANSIT SYSTEM -----------8 3.0 SERVICE PLANNING AND EVALUATION------------------------------------- 20 4.0 OPERATING PLAN ------------------------------------------------------------------- 32 5.0 CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PLANNING ----------------------------------------- 53 6.0 STRATEGIC PLANNING AND MARKETING---------------------------------- 65 7.0 CONCLUSION ------------------------------------------------------------------------- 70 TABLES 2.1 SACRAMENTO’S TRANSIT HISTORY ------------------------------------------8 2.2 DISTRICT FACTS AND OPERATING CHARACTERISTICS------------- 11 2.3 FARE PAYMENT METHODS BY DURATION--------------------------------15 2.4 USE OF DISCOUNT FARES------------------------------------------------------16 2.5 SPECIAL PASSES AND NON-PAYING PASSENGERS------------------- 17 4.1 NUMBER OF BUS ROUTES BY DAY ------------------------------------------ 32 4.2 BUS HEADWAYS -------------------------------------------------------------------- 33 4.3 AVERAGE DAILY RIDERSHIP BY LIGHT RAIL STATION--------------- 38 4.4 RIDERSHIP, REVENUE, REVENUE HOUR, AND COST TRENDS TRENDS AND PROJECTIONS THROUGH FY 2021 ----------------------41 4.5 PRODUCTIVITY TRENDS -

2018-19 State of Good Repair Approved Project List

2018-19 State Of Good Repair Approved Project List 2018-19 Project Location Estimated total # Recipient Sub-Recipient Project Title Project Description City SGR Allocation Amount* 1 San Joaquin Council of Governments San Joaquin Regional Rail Commission - to Altamont Facility Upgrades and Improvements The Western Pacific Depot building, adjacent to the Robert Stockton Corridor Express (ACE) J. Cabral Station, is currently in a state of disrepair due to a fire. The building will be rehabilitated for future use by ACE $256,937 passengers and SJRRC employees. Metropolitan Transportation Commission Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority - to Facility Upgrades and Improvements The Western Pacific Depot building, adjacent to the Robert Stockton Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) J. Cabral Station, is currently in a state of disrepair due to a fire. The building will be rehabilitated for future use by ACE $31,362 passengers and SJRRC employees. Metropolitan Transportation Commission Alameda County Congestion Management Agency - to Facility Upgrades and Improvements The Western Pacific Depot building, adjacent to the Robert Stockton Altamont Corridor Express (ACE) J. Cabral Station, is currently in a state of disrepair due to a fire. The building will be rehabilitated for future use by ACE $40,599 passengers and SJRRC employees. San Joaquin Council of Governments San Joaquin Joint Powers Authority - to Altamont Facility Upgrades and Improvements The Western Pacific Depot building, adjacent to the Robert Stockton Corridor Express (ACE) J. Cabral Station, is currently in a state of disrepair due to a fire. The building will be rehabilitated for future use by ACE $44 passengers and SJRRC employees. 2 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Metropolitan Transportation Commission Clipper®/Clipper® 2.0 Replacement and modernization of the San Francisco Bay All 101 cities of the San Area's Clipper electronic transit fare payment system Francisco Bay Area $10,250,287 which is used by 22 transit operators. -

Regulatory Setting

TRANSPORTATION AND CIRCULATION | 3 Regulatory Setting Federal Safe and Complete Streets Act of 2011 (HR 1780 & S 1056) On May 5, 2011, Representatives Matsui and LaTourette of California introduced HR 1780, the Safe and Complete Streets Act of 2011, on the U.S. House floor. On May 24, 2011, Senator Harkin of Iowa and several other senators introduced a companion bill, S 1056, on the U.S. Senate floor. These bills were crafted to ensure that all users of the transportation system, including bicyclists, pedestrians, children, transit users, older adults, and disabled people, are able to travel safely and conveniently on the nation’s roadways. At present, the bills remain in committee awaiting approval to be reviewed by their respective whole legislative bodies. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) legislation prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability. Other Federal laws which affect the design, construction, alteration, and operation of facilities include the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) of 1968 and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. These laws apply to all Federally-funded facilities. The ADA applies to facilities, both public (Title II) and private (Title III), which are not Federally-funded. Newly constructed and altered facilities covered by Titles II and III of the ADA must be readily accessible to and usable by people with disabilities. In July 1999, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) issued an Accessibility Policy Statement pledging a fully accessible and multimodal transportation system. Accessibility in Federally-assisted programs is governed by the USDOT regulations (49 CFR part 27) implementing Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (29 U.S.C. -

Triennial Performance Audit

El Dorado County Transit Authority Triennial Performance Audit for Fiscal Years 2015-16, 2016-17, and 2017-18 Prepared for the El Dorado County Transit Authority Prepared by TRIENNIAL PERFORMANCE AUDIT of the EL DORADO COUNTY TRANSIT AUTHORITY for Fiscal Years 2015-16 through 2017-18 Final Prepared for the El Dorado County Transportation Commission 2828 Easy Street Placerville, California 95667 530 • 642-5260 Prepared by LSC Transportation Consultants, Inc. P.O. Box 5875 2690 Lake Forest Road, Suite C Tahoe City, California 96145 530 • 583-4053 May 15, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 Performance Audit Report and Organization .................................................................................. 1 Background ...................................................................................................................................... 1 EDCTA Operating and Financial Statistics ........................................................................................ 1 Review of Compliance Requirements .............................................................................................. 2 Status of Prior Audit Recommendations ......................................................................................... 2 Detailed Review of Transit Operator Functions ............................................................................... 2 Findings ........................................................................................................................................... -

FY 2017-18 Approved SGR Project List (PDF)

2017-18 State of Good Repair Approved Project List 2017-18 Recipient Sub-Recipient Project Title Estimiated Total SGR Allocation Amount* Metropolitan Transportation Commission Alameda-Contra Costa Transit District East Bay Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) $ 3,149,541 Metropolitan Transportation Commission San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District Railcar Procurement Project $ 10,247,507 Metropolitan Transportation Commission San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District STA SGR Preventative Maintenance $ 6,102,066 Metropolitan Transportation Commission City of San Francisco Muni Facility Rehabilitation Campaign $ 9,513,519 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Central Contra Costa Transit Authority Intelligent Transportation System Security Maint $ 119,162 Metropolitan Transportation Commission City of Dixon - Funds to Soltrans $ - Metropolitan Transportation Commission Eastern Contra Costa Transit Authority Replacement of Damaged or Missing Bus Shelters $ 55,157 Metropolitan Transportation Commission City of Fairfield Local Bus Fleet Replacement $ 26,276 Golden Gate Bridge Highway and Transportation Metropolitan Transportation Commission District MS Marin Ferry Boat Repower and Dry Dock $ 578,261 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Livermore-Amador Valley Transit Authority Bus Shelter and Stop Maintenance $ 55,640 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Marin County Transit District Purchase One Shuttle Vehicle $ 130,000 Metropolitan Transportation Commission Marin County Transit District MCTD: Replace Four (4) Rural cutaway vehicles $ -

OVERALL WORK PROGRAM SACOG-11-001 Fiscal Year 2011-12

OWP OVERALL WORK PROGRAM SACOG-11-001 Fiscal Year 2011-12 Adopted May 19, 2011 Sacramento Area Council of Governments 1415 L Street Suite 300 Sacramento, CA 95814 tel: 916.321.9000 fax: 916.321.9551 www..sacog.org SACOG MISSION BOARD MEMBER Provide leadership MEMBERS COUNTIES & and a dynamic, CITIES Susan Peters Kevin Johnson collaborative public (Chair) City of Sacramento Sacramento County El Dorado County forum for achieving John Knight Placer County Peter Hill El Dorado County Sacramento County an efficient (Vice Chair) Sutter County City of Rocklin Joe Krovoza Yolo County regional City of Davis Yuba County John Allard City of Auburn transportation City of Roseville Roberta MacGlashan City of Citrus Heights Sacramento County system, innovative City of Colfax Harold Anderson City of Davis Leslie McBride and integrated City of Winters City of Elk Grove City of Yuba City City of Folsom Christina Billeci City of Galt regional planning, Steve Miklos City of Marysville City of Isleton City of Folsom and a high quality City of Lincoln Linda Budge City of Live Oak of life within the City of Rancho Cordova Steve Miller City of Citrus Heights Town of Loomis City of Marysville Christopher Cabaldon greater Sacramento City of Placerville City of West Sacramento Larry Montna City of Rancho Cordova region. Sutter County Steve Cohn City of Rocklin City of Roseville City of Sacramento Barbara Payne City of Galt City of Sacramento Tom Cosgrove City of West Sacramento City of Lincoln Suzanne Roberts City of Wheatland City of Colfax City of Winters Gary -

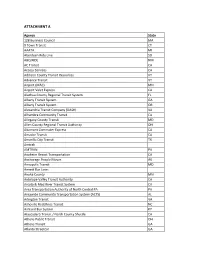

Attachment A

ATTACHMENT A Agency State 128 Business Council MA 9 Town Transit CT AAATA MI Aberdeen Ride Line SD ABQ RIDE NM AC Transit CA Access Services CA Addison County Transit Resources VT Advance Transit VT Airport (MAC) MN Airport Valet Express CA Alachua County Regional Transit System FL Albany Transit System GA Albany Transit System OR Alexandria Transit Company (DASH) VA Alhambra Community Transit CA Allegany County Transit MD Allen County Regional Transit Authority OH Altamont Commuter Express CA Amador Transit CA Amarillo City Transit TX Amtrak AMTRAN PA Anaheim Resort Transportation CA Anchorage People Mover AK Annapolis Transit MD Annett Bus Lines Anoka County MN Antelope Valley Transit Authority CA Arcata & Mad River Transit System CA Area Transportation Authority of North Central PA PA Areawide Community Transportation System (ACTS) AL Arlington Transit VA Asheville Redefines Transit NC Ashland Bus System KY Atascadero Transit / North County Shuttle CA Athens Public Transit OH Athens Transit GA Atlanta Streetcar GA Atlantic Station Shuttle GA Atomic City Transit NM Auburn Transit (Placer County Department of Public Works) CA Augusta Public Transit GA Avila Trolley CA Baker City Community Connection OR Banning Transit CA Barstow Area Transit CA Bart Bus WI Basin Transit Service OR Battle Creek Transit MI Bay Area Rapid Transit CA Bay Area Transportation Authority MI Bay Metro MI Bay State Cruise Company MA Bay Town Trolley FL Baylink CA BCTA (Beaver County Transit Authority) PA BE Line CA Beach Cities Transit - City of Redondo Beach (BCT) -

Transit Master Plan

Placer County Transportation Planning Agency Transit Master Plan for South Placer County CTSA • Auburn Transit • Lincoln Transit • Placer County Transit • Roseville Transit • Consolidated Transportation Services Agency Prepared by URS CORPORATION With the assistance of DKS Associates, Inc. June 2007 Placer County Transportation Planning Agency Transit Master Plan for South Placer County TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY OF FINDINGS AND OPPORTUNITIES ................................... S-1 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................1 1.1 Background and Purpose.................................................................................... 1 1.2 Master Plan Objectives ....................................................................................... 1 1.3 Master Plan Participants and Development Process........................................... 2 1.4 Organization of This Document........................................................................... 2 2.0 Existing Transit Service and Public Perceptions.................................3 2.1 Existing Transit Service....................................................................................... 3 2.2 Public Outreach Findings .................................................................................... 3 3.0 Conceptual Long-Range Service Plan ..................................................8 3.1 Background and Approach.................................................................................. 8