HISTORICAL BACKGROUND INFORMATION for SOME of the DESIGNS That Is Not Necessarily Depicted in the Exhibits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Festive Tours: Further Information Or Simply to Book

September 2019, let’s hope for an Indian Summer to WW1 : I am delighted to enjoy a few more lighter days. We have been very lucky announce that by request we now with our tours this summer enjoying decent weather just have a tour in 2020 to the Battlefields when we have needed it. of the Great War. Dave will be Fred Olsen have launched a new selection of offers don’t returning to guide us around the area miss out on these savings. Beth is an ardent cruiser and and this tour is to include special loves her cruises on board Fred Olsen. She has just places that you our guests are returned from Norway and was amazed at the stunning requesting to visit along with many scenery and hot weather! She knows the Fred ships main inclusions. For example Tyncote, Vimmy Ridge, The Last Post and Oppy inside out and looks forward to telling you more. Wood for the Hull Pals. You will find Hot off the press I have just added two more escorted more information inside but do feel holidays by air. A cruise through the Panama Canal which free to contact me for a chat and of ticks lots off the bucket list visiting Mexico, Nicaragua, course let me know if you have a Guatamala, Costa Rica, Columbia and the Cayman Isles! special place for us to include. This an The second is an exclusive itinerary visiting Georgia and enriching and emotional tour. Armenia. Further details of both departures can be found inside this booklet, or simply give me a call for Festive tours: further information or simply to book. -

THE BLACKMAIL the Routledge Clan Society Newsletter

THE BLACKMAIL The Routledge Clan Society Newsletter NOVEMBER 2018 We Will Remember Them 40 1 Chairman's Thoughts was a hell that we will never comprehend or understand. The Sergeant John Ratlidge 13337, MM, MiD trenches, injures, disease and shelling so constant that it 10th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (West Riding) Regiment As most of you know I am a serving member of the British created a condition known only to WW1; Shell shock, where Awarded MM, 29th March 1919 Royal Air Force and therefore I have a very strong tie to the nervous system was literally shattered. remembrance and the assurance that lives given will not be Forget the tactics, the countries, the marching towards John Ratlidge was 22 years old when he enlisted and one of nine children of Henry and Mary Ellen Ratlidge. Three of John’s forgotten, nor their deeds undervalued or taken for granted. machine guns like a Napoleonic cavalry charge and even forget siblings had died in infancy and his mother had also died in 1909. By 1911 the family was living in Keighley, where Henry Our freedom to think, act and say what and how we wish has the number being slaughtered. Concentrate on the individual. worked for the local corporation as a road repairer and John, though only 15, was an overlocker at a worsted spinning mill. been built on a foundation of those who were willing or did Regardless as to the patriotic reason they went to war, or even John Ratlidge was an original member of the Battalion, having enlisted in September 1914 and had been promoted Lance give the ultimate sacrifice. -

A History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference To

The History of 119 Infantry Brigade in the Great War with Special Reference to the Command of Brigadier-General Frank Percy Crozier by Michael Anthony Taylor A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2016 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract 119 Brigade, 40th Division, had an unusual origin as a ‘left-over’ brigade of the Welsh Army Corps and was the only completely bantam formation outside 35th Division. This study investigates the formation’s national identity and demonstrates that it was indeed strongly ‘Welsh’ in more than name until 1918. New data on the social background of men and officers is added to that generated by earlier studies. The examination of the brigade’s actions on the Western Front challenges the widely held belief that there was an inherent problem with this and other bantam formations. The original make-up of the brigade is compared with its later forms when new and less efficient units were introduced. -

1892-1929 General

HEADING RELATED YEAR EVENT VOL PAGE ABOUKIR BAY Details of HM connections 1928/112 112 ABOUKIR BAY Action of 12th March Vol 1/112 112 ABUKLEA AND ABUKRU RM with Guards Camel Regiment Vol 1/73 73 ACCIDENTS Marine killed by falling on bayonet, Chatham, 1860 1911/141 141 RMB1 marker killed by Volunteer on Plumstead ACCIDENTS Common, 1861 191286, 107 85, 107 ACCIDENTS Flying, Captain RISK, RMLI 1913/91 91 ACCIDENTS Stokes Mortar Bomb Explosion, Deal, 1918 1918/98 98 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of Major Oldfield Vol 1/111 111 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Turkish Medal awarded to C/Sgt W Healey 1901/122 122 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Ball at Plymouth in 1804 to commemorate 1905/126 126 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Death of a Veteran 1907/83 83 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1928/119 119 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Correspondence 1929/177 177 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) 1930/336 336 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) Syllabus for Examination, RMLI, 1893 Vol 1/193 193 ACRE, SORTIE FROM (1799) of Auxiliary forces to be Captains with more than 3 years Vol 3/73 73 ACTON, MIDDLESEX Ex RM as Mayor, 1923 1923/178 178 ADEN HMS Effingham in 1927 1928/32 32 See also COMMANDANT GENERAL AND GENERAL ADJUTANT GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING of the Channel Fleet, 1800 1905/87 87 ADJUTANT GENERAL Change of title from DAGRM to ACRM, 1914 1914/33 33 ADJUTANT GENERAL Appointment of Brigadier General Mercer, 1916 1916/77 77 ADJUTANTS "An Unbroken Line" - eight RMA Adjutants, 1914 1914/60, 61 60, 61 ADMIRAL'S REGIMENT First Colonels - Correspondence from Lt. -

Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme

This is a repository copy of Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/99480/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Spiers, EM (2016) Yorkshire and the First Day of the Somme. Northern History, 53 (2). pp. 249-266. ISSN 0078-172X https://doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601 © 2016, University of Leeds. This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis in Northern History on Sep 2016, available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0078172X.2016.1195601. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 YORKSHIRE AND THE FIRST DAY OF THE SOMME EDWARD M. -

EYLHS Newsletter 26 Winter / Spring 2012

EYLHS Newsletter 26 Winter / spring 2012 Newsletter of the East Yorkshire Local History Society Front cover: Hull Infirmary, Prospect St, engraving from Hull Hospital Unit archives Contributions Based in Hull it is not always easy to keep track of events in other parts of the Riding; news that members could contribute on their town or village should be sent to the editor. Short articles, illustrated or unillustrated, news on libraries, archives, museums, societies or education, queries other people may be able to answer, etc. for inclusion in future newsletters should also be sent to the editor. Newsletter Edited by Robert Barnard 825 Anlaby Rd, Hull, HU4 6DJ Telephone 01482 506001 e-mail [email protected] Published by the East Yorkshire Local History Society Secretary Jenny Stanley 15 Southcote Close, South Cave, HU15 2BQ Telephone 01430 422833 e-mail [email protected] Printed by Kall Kwik, Hull News from the Society Programme recently achieved his Doctorate which As usual, the Society has arranged a full was based on this theme. programme of lectures and excursions Commences 2.00pm for 2012. Please support the events Bridlington Central Library (Lecture and bring along your friends. Please do Room on 1st floor), King Street, not hesitate to ask for lifts; you will be Bridlington expected to contribute to petrol. Car Parking near Harbour £2 per person for tea/coffee and PLEASE NOTE: Please make all biscuits cheques payable to the East Yorkshire Local History Society. All cheques Saturday 14 April 2012 and booking slips should be sent to Ed Dennison the relevant named individual at the ‘Recent Work in the East Riding’, a address on the booking form. -

Download PDF Version of Vol. 118 No. 11

Ethical Record The Proceedings of the Conway Hall Ethical Society Vol. 118 No. 11 £1.50 December 2013 EDITORIAL - A CONVENIENT TIME TO ‘FIRE’ TRIDENT? The recent publication of a document outlining the plans for an independent Scotland raised the question of how such a state would defend itself. The document suggested that the process of shutting down the UK’s submarine base in Faslane should be started. Naturally, that would not please the British Government, which would have the difficult job of building another base somewhere else. So the UK began presenting spurious arguments against this possibility, such as that Scotland would be excluded from NATO. But having nuclear weapons is not a condition of membership of NATO; the USA, the UK and (when it feels like it) France, are the only nuclear powers in NATO. In any case, Scotland can offer other military assets to NATO involving much less risk to itself. The real point is that Faslane is a strategic weakness in the Trident system because it’s a fixed target of major importance. The advantage of being able to launch one’s missiles from submarines when at sea is their (alleged) untraceability and hence invulnerability – but the base represents a quite unnecessary danger to Scotland. I hope its days are numbered. Public pressure famously forced the UK to remove those US missiles which could be launched from England. It’s time, therefore, to cancel the costly proposals for new subs and mothball the existing ones. The UK is treaty-bound to oppose nuclear proliferation, a deadly threat to the world, which it won’t achieve unless it demonstrates the will to lead the world’s ‘2nd eleven’ nuclear powers (ie, ALL except the big two, USA and Russia) in a scheme for multilateral nuclear disarmament. -

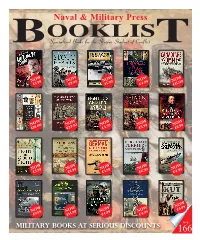

List at £18.00 Saving £10 from the Full Published Price

Naval & Military Press Specialised Books for the Serious Student of Conflict NOW £5.99 NOW £9.99 NOW £5.99 NOW NOW £4.99 £18.00 NOW NOW £15.00 £27.50 NOW £4.99 NOW NOW £3.99 £5.99 NOW NOW £6.99 £6.99 NOW £3.99 NOW NOW £6.99 £9.99 military books at serious discounts NOW NOW £4.99 £14.99 NOW £4.99 NOW £4.99 NOW £6.99 166Issue A new “Westlake” classic A Guide to The British Army’s Numbered Infantry Regiments of 1751-1881 Ray Westlake An oversized 127 page softback published by The Naval & Military Press, September 2018. On Early Bird offer with this Booklist at £18.00 saving £10 from the full published price. Order No: 27328. This book, the first in a series of British Army ‘Guides’, deals with the numbered regiments that existed between 1751, when the British infantry was ordered to discard their colonels’ names as titles and be known in future by number only (1st Regiment of Foot, 2nd Regiment of Foot, etc), and 1881 when numerical designations were replaced by the now familiar territorial names such as the Hampshire Regiment or Middlesex Regiment. The book provides the formation date of each regiment, names of colonels prior to 1751, changes of title, battle honours awarded before 1881 and brief descriptions of uniform and badges worn. Helpful to the collector will be the badge authorisation dates included. With a view to further research, details of important published regimental histories have been noted. The numbering of infantry regiments reached 135 but, come the reforms of 1881, only 109 were still in existence. -

How Should Sport Remember? a British Future Essay Authors

How Should Sport Remember? A British Future essay Authors: Sunder Katwala and Matthew Rhodes INTRODUCTION The largest collective acts of commemoration this 2012 remembrance weekend will take place at sporting events. Cardiff Arms Park, Murrayfield and Twickenham will fall silent ahead of the rugby internationals, and more than half a million supporters will pay their respects at club grounds, large and small, around Britain. The red poppies embroidered into football shirts in the English and Scottish premier leagues, a relatively recent development, symbolize how remembrance has become more prominent, not less over the last decade, in sport as in society. This year’s remembrance weekend should also be a chance to begin a public conversation about how sport will mark the centenary of the Great War, the year after next. Should national civic activities to mark 2014 include specific activities of sporting commemoration? Not everybody will instinctively think it should. Some may prefer sport and remembrance to be kept apart, perhaps feeling that military engagement in sporting events may be more suited to US than British sporting culture. Some may prefer that the Great War centenary should be marked in national ceremonies at the Cenotaph and Westminster Abbey, and educational exhibitions in military museums, but doubt that our national games offer as appropriate a forum for solemn remembrance. Those who know our sporting history can find in it a powerful, persuasive counter-argument: that sport has a special responsibility to commemorate and remember the Great War, which goes beyond its contemporary role as a prominent gathering place in our modern civic life. -

TEL: 01482 212525 - Office Hours: Mon-Fri 9Am - 4Pm (We Have Our Own Small Car Park) : Saturday - Telesales Only

August 2019, Last month we had yet another excellent WW1 : I am delighted to tour on the Isles of Scilly. I do keep being asked to repeat announce that by request we now tours hence we have now started lists of interested have a tour in 2020 to the Battlefields guests for each destination. I am planning on revisiting of the Great War. Dave will be the Isles of Scilly 2021 & Highgrove in 2020 plus other returning to guide us around the area tours subject to numbers. Do let me know if you wish to and this tour is to include special be on any of the lists. places that you our guests are Saga’s new ship Discovery is an amazing ship. Emma and requesting to visit along with many I really enjoyed every aspect of the ship, accommodation, main inclusions. For example Tyncote, food, service and the selection of public areas to choose Vimmy Ridge, The Last Post and Oppy Wood for the Hull Pals. You will find from. So much is always included in the cost; speciality more information inside but do feel restaurants, gratuities & drinks. If you would like to make free to contact me for a chat and of a booking or hear more about the ship please do not course let me know if you have a hesitate to ask. We have a good supply of brochures in special place for us to include. This an the office available too. enriching and emotional tour. OFFERS too numerous to mention! We have 1000’s please just ask for anything you are interested in and we Festive tours: will do the leg work to get you the best offer. -

Cet Ouvrage a Été Publié Avec Le Concours Et Le

Rd Responsable du volum: Col. (R) Dr. Gh. Nicolescu Traduction en français: Ruxandra Lupan Cet ouvrage a été publié avec le concours et le généreux appui de la FONDATION „GENERAL ŞTEFAN GUŞA” COMMISSION FRANÇAISE COMMISSION ROUMAINE D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE D’HISTOIRE MILITAIRE GUERRE ET SOCIÉTÉ EN EUROPE Perspectives des nouvelles recherches Coordination générale: Prof. émérite Dr André CORVISIER Prof. Dr Dumitru PREDA Editions EUROPA NOVA BUCAREST 2004 2 Couverture: Maria PAŞOL Mise en pages: Mariana IONIŢĂ ISBN 973-8158-38-9 Imprimé en Roumanie. 3 GUERRE ET SOCIÉTÉ EN EUROPE Perspectives des nouvelles recherches ans l’historiographie militaire, plus que dans les autres domaines de l’histoire, les barrières culturelles, tout comme DD les frontières nationales constituent une difficulté pour la recherche. C’est contre quoi lutte la Commission Internationale d’Histoire Militaire, en proposant à ses membres (une trentaine de commissions nationales) des études en commun de thèmes bien définis. Ces confrontations permettent des réflexions qui, au-delà de la consolidation de nos connaissances, invitent à des interprétations plus objectives des sensibilités nationales et des comportements des hommes. Plus rares sont les appels adressés par les historiens d’une nation à leurs collègues des autres pays pour s’informer de leurs méthodes et amorcer ou renforcer les échanges. Aussi convient-il de saluer l’initiative d’un jeune historien français, Emanuel Constantin Antoche, visant à établir des contacts directs entre la France et la Roumanie au moyen d’une publication commune. D’origine roumaine, il a suivi d’une manière constante, entre 1992 et 1998, les travaux de mon séminaire «Armées et Sociétés» à la Sorbonne où il a présenté plusieurs exposés concernant l’art militaire en Europe Centrale et Orientale, axés particulièrement sur l’histoire de la Roumanie aux époques médiévale et moderne: La stratégie de Vlad l’Empaleur, prince de Valachie contre les Ottomans pendant la guerre de 1461-1462 (séance de 01.12.1992 avec le professeur Matei Cazacu); Deux ans après Poltava. -

First World War Items Held in East Riding Museums Service Collections

First World War items held in East Riding Museums Service collections ID Number Description ERYMS : Brass East Yorkshire Volunteers battalion shoulder badge - with the four letters joined together. 1995.722 Pin in slide on back. Probably dates to the period of the First World War. ERYMS : Hexagonal bronze Peace Medal 1914-1918 war, with Peace Celebration, the 3B's shield with 19 on 1996.1095 each side of it, the word Bridlington in a scroll beneath it, and Ernest Lambert Mayor at the bottom. On the reverse side 'To the honour of our gallant sea, land and air forces which under God brought victory and peace'. A bronze clasp with a pin worded, 'Finis a dest belli sunt et sua munera paci' and a black and white ribbon. ERYMS (BAG) : Bronze medal depicting head and shoulders of an army officer on one side, marked 'C.M. 1998.448 Schwerdtner'; and the reverse shows a soldier with a rifle standing on a mountain. Probably WWI period. Part of a group found with a plaque marked '15' (1998.17). Probably an art medal rather than a military item as such. ERYMS : Gilt metal and enamel shield with old Bridlington coat of arms and crown above, shield enclosed in 1995.724 scrolls, dark blue, yellow and red enamel. Legend - 'Bridlington Volunteer Force'. On reverse the number 107. ERYMS (BAG) : Iron (?) medal with 'ROGER CASEMENT'on one side and a portrait of a man being executed, plus 1998.461 inscription in German; a book (dated 1351), a spider and a web on the other.