Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro

25 Recommended Recordings of Negro Spirituals for Solo Vocalist Compiled by Randye Jones This is a sample of recordings recommended for enhancing library collections of Spirituals and, thus, is limited (with one exception) to recordings available on compact disc. This list includes a variety of voice types, time periods, interpretative styles, and accompaniment. Selections were compiled from The Spirituals Database, a resource referencing more than 450 recordings of Negro Spiritual art songs. Marian Anderson, Contralto He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands (1994) RCA Victor 09026-61960-2 CD, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, J. Rosamond Johnson, Hamilton Forrest, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, Roland Hayes Spirituals (1999) RCA Victor Red Seal 09026-63306-2 CD, recorded between 1936 and 1952, with piano Songs by Hall Johnson, John C. Payne, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, Hamilton Forrest, Robert MacGimsey, Roland Hayes, Florence Price, Edward Boatner, R. Nathaniel Dett Angela Brown, Soprano Mosiac: a collection of African-American spirituals with piano and guitar (2004) Albany Records TROY721 CD, variously with piano, guitar Songs by Angela Brown, Undine Smith Moore, Moses Hogan, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Margaret Bonds, Florence Price, Betty Jackson King, Roland Hayes, Joseph Joubert Todd Duncan, Baritone Negro Spirituals (1952) Allegro ALG3022 LP, with piano Songs by J. Rosamond Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Lawrence Brown, William C. Hellman, Edward Boatner Denyce Graves, Mezzo-soprano Angels Watching Over Me (1997) NPR Classics CD 0006 CD, variously with piano, chorus, a cappella Songs by Hall Johnson, Harry T. Burleigh, Marvin Mills, Evelyn Simpson- Curenton, Shelton Becton, Roland Hayes, Robert MacGimsey Roland Hayes, Tenor Favorite Spirituals (1995) Vanguard Classics OVC 6022 CD, with piano Songs by Roland Hayes Barbara Hendricks, Soprano Give Me Jesus (1998) EMI Classics 7243 5 56788 2 9 CD, variously with chorus, a cappella Songs by Moses Hogan, Roland Hayes, Edward Boatner, Harry T. -

Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications: School of Music Music, School of 8-26-2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, and the Music Commons Lefferts, Peter M., "Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography" (2016). Faculty Publications: School of Music. 64. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicfacpub/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications: School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1 08/26/2016 Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of J. Tim Brymn Materials for a Biography Peter M. Lefferts University of Nebraska-Lincoln This document is one in a series---"Chronology and Itinerary of the Career of"---devoted to a small number of African American musicians active ca. 1900-1950. They are fallout from my work on a pair of essays, "US Army Black Regimental Bands and The Appointments of Their First Black Bandmasters" (2013) and "Black US Army Bands and Their Bandmasters in World War I" (2012/2016). In all cases I have put into some kind of order a number of biographical research notes, principally drawing upon newspaper and genealogy databases. None of them is any kind of finished, polished document; all represent work in progress, complete with missing data and the occasional typographical error. -

Chanticleer Christmas 2018 Reader

A Chanticleer Christmas WHEN: VENUE: WEDNESDAY, MEMORIAL CHURCH DECEMBER 12, 2018 7∶30 PM Photo by Lisa Kohler Program A CHANTICLEER CHRISTMAS Cortez Mitchell, Gerrod Pagenkopf*, Kory Reid Alan Reinhardt, Logan Shields, Adam Ward, countertenor Brian Hinman*, Matthew Mazzola, Andrew Van Allsburg, tenor Andy Berry*, Zachary Burgess, Matthew Knickman, baritone and bass William Fred Scott, Music Director I. Corde natus ex parentis Plainsong Surge, illuminare Jerusalem Francesco Corteccia (1502–1571) Surge, illuminare Jerusalem Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594) II. Angelus ad pastores ait Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Quem vidistis, pastores dicite Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) Quem vidistis, pastores? Orlando di Lasso (1532–1594) D’où viens-tu, bergère? Trad. Canadian, arr. Mark Sirett Bring a Torch, Jeanette, Isabella Trad. French, arr. Alice Parker and Robert Shaw III. Nesciens mater Jean Mouton (1459–1522) O Maria super foeminas Orazio Vecchi (1550–1605) Ave regina coelorum Jacob Regnart (1540–1599) IV. Here, mid the Ass and Oxen Mild Trad. French, arr. Parker/Shaw O magnum mysterium+ Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) Behold, a Simple, Tender Babe Peter Bloesch (b. 1963) World Premier performances V. Hacia Belén va un borrico Trad. Spanish, arr. Parker/Shaw Staffan var en stalledräng Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (b. 1963) Commissioned in 2016 by Gayle and Timothy Ober, Allegro Fund of The Saint Paul Foundation, in honor of their 35th wedding anniversary. Chanticleer Trad. English, arr. Philip Wilder ¡Llega la Navidad! Ramón Díaz (1901–1976), arr. Juan Tony Guzmán —INTERMISSION— 2 VI. Ave Maria+ Franz Biebl (1906–2001) Bogoróditse Dyévo, ráduisya Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) VII. A selection of popular carols to be chosen from… Up! Good Christen Folk Trad. -

The Evolution of Eva Jessye's Programming As Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982

The Evolution of Eva Jessye's Programming as Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jenkins, Lynnel Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 23:30:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/622962 THE EVOLUTION OF EVA JESSYE’S PROGRAMMING AS EVIDENCED IN HER CHORAL CONCERT PROGRAMS FROM 1927-1982 by Lynnel Jenkins __________________________ Copyright © Lynnel Jenkins 2016 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Lynnel Jenkins, titled The Evolution of Eva Jessye’s Programming as Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree. ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 Bruce Chamberlain ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 Elizabeth Schauer ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 John Brobeck Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Title Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of mixed John W. Work 1952 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0110 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of women's John W. Work 1949 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0109 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals I Want Jesus to Walk with Me Edward Boatner 1949 1121-113-001_0028 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Lord, I'm out Here on Your Word for John W. Work 1952 unaccompanied mixed chorus 1121-113-001_0111 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Lincoln Letter Ulysses Kay 1958 1121-113-001_0185 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Like as a Father Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0188 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus O Praise the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0187 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Sing Unto the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0186 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Wreath for Waits II. Lully, Lully Ulysses Kay 1956 1121-113-001_0189 1121-113-001 Associated Music Publishers Aeolian Choral Series King Jesus is A-Listening, negro folk song William L. -

Hall Johnson's Choral and Dramatic Works

Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Wittmer, Micah. 2016. Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939). Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:26718725 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) A dissertation presented by Micah Wittmer To The Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Music Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January, 2016 © 2016, Micah Wittmer All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Carol J. Oja Micah Wittmer -- Performing Negro Folk Culture, Performing America: Hall Johnson’s Choral and Dramatic Works (1925-1939) Abstract This dissertation explores the portrayal of Negro folk culture in concert performances of the Hall Johnson Choir and in Hall Johnson’s popular music drama, Run, Little Chillun. I contribute to existing scholarship on Negro spirituals by tracing the performances of these songs by the original Fisk Jubilee singers in 1867 to the Hall Johnson Choir’s performances in the 1920s-1930s, with a specific focus on the portrayal of Negro folk culture. -

Lift Every Voice: Celebrating the African American Spirit

Lift Every Voice: Hear My Prayer Moses Hogan Celebrating the African American Spirit Set Me as a Seal Julius Miller Saturday, February 22. , 2014 7:30 pm Lord We Give Thanks to Thee Undine Smith Moore Campus Auditorium Lift Every Voice and Sing arr. Roland Carter South Bend Symphonic Choir How Great is Our God Chris Tomlin Naomi Penate, alto Jake Hughes, tenor CONDUCTOR BIOGRAPHIES For Every Mountain Kurt Carr Gwen Norwood, alto David Brock was born and raised in Benton Harbor, Mich. to the union of Walter and the late Doris Brock. He started playing I’m Determined Oscar Hayes the piano at the age of six and began taking lessons at age 11. He also began playing piano at churches when he was 11. Mr. Brock Hallelujah Elbernita “Twinkie” Clark performed in bands and orchestras throughout his education. He IU South Bend Gospel Choir attended Olivet College where he studied music. Mr. Brock is Formatted: Font: Not Bold currently employed at Benton Harbor High School as a pianist and Dich Teure Halley Richard Wagner assistant music teacher. He teaches keyboard theory and voice. He has been playing the keyboard for 44 years. Witness Hall Johnson Marvin Curtis, dean of the Ernestine M. Raclin School of You Can Tell the World Margaret Bonds the Arts at Indiana University South Bend is director of the South Denise Payton, soprano Bend Symphonic Choir. Dean Curtis has held positions at Intermezzo, Op. 118, No. #2 Johannes Fayetteville State University, California State University, Brahms Stanislaus, Virginia Union University, and Lane College. He earned degrees from North Park Troubled Water Margaret Bonds College, The Presbyterian School of Christian Education, Formatted: Indent: First line: 0.5" Maria Corley, piano and The University of the Pacific, and took additional studies at Westminster Choir College and The Julliard School of Music. -

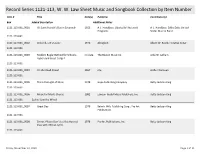

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0001 It's Saint Patrick's Day in Savannah 1953 A. J. Handiboe; Liberty Bell Network A. J. Handiboe; Eddie Daly; United Programs States Marine Band 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0002 Beloved, Let Us Love 1976 Abingdon Albert W. Ream; Horatius Bonar 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0003 Modern Bugle Method for Schools, no date The Boston Music Co. Arlie W. Latham Legion and Scout Corps 1 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0004 On the Road Ahead 1967 n/a Arthur Donovan 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0005 This Little Light of Mine 1978 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0006 Music for Men's Chorus 1982 Lawson-Gould Music Publishers, Inc. Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 Ezekiel Saw the Wheel 1121-113-001_0007 Great Day 1976 Belwin Mills Publishing Corp.; Pro Art Betty Jackson King Publications 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0008 Sinner, Please Don't Let this Harvest 1978 Pro Art Publications, Inc. Betty Jackson King Pass with African Lyrics 1121-113-001 Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0009 Marks Choral Library 1973 Edward B. Marks Music Corporation; Belwin Betty Jackson King Mills Publishing Corp. 1121-113-001 I Want God's Heaven to be Mine 1121-113-001_0010 Stand the Storm 1980 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0011a God is a God! 1983 Mar-Vel Betty Jackson King; Roland M. -

For Sewer Investigation

.^ c .w;.v.;^u.'u^v:^ RAHWAY RECORD, TUESDAY, JUNE 10,1930 WfeATHER /oitECAST ; , ; ' PUBL.I8HED Today: Cloudy, illghtly warmer. TV/ICE WEEKLY Tomorrow: F»|r, not much change In ttmper«tUT0. IN RAHWAY'S INTEpE8T8 '• The New Jersey Advocate Announcing Absorbing Tht Rahyyay Newa-Hcrald, the successor of the Union Democrat, Established 1840 ANOTHER VOL. XIX. SERIAL NO. 2152 Sixteen Pages PRICE THREE CENTS ] Mi RAHWAY, UNION CflUNTY, N! J., FRIDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 13,1930 WILL GfeAdUAtE WITH HIGHEST-HONORS r ''''.>".•.5": PROPERTY FOR PARK Corner Lake Avenue and St. George ^Avenue. FOR SEWER INVESTIGATION Tracts of Land, Including SquUr THE MANAGEMENT OF - idfD Ordinance PassedUAfter-Long Mt&cusswn iou.nl of Adjustment By Councilman andr-Gitizens-t-Engineer- A BoafoV of Adjustment to Questioned oh Workmanship carry out the provisions of the The same prompt and courteous treatment will be given, as tbat which has made our Station at Milton Avenue and Irving Street a success. LAND IN SQUIER FAMILY 151 YEARS zoning ordinance which was re- cently passed for this city, -was .appointed-by Mayor Adolph Ul- MONEY FOR CITIZENS' COMMITTEE brlch and announced at the Upohtherecomm^datiohofMayor^lolpfrui= meeting of the. Common Ooun- brich,'the Common Council at its meeting Wedne^ .cILWednesday night.' :_'_ . At the conclusion of a two-hour discussion, the. —The—personnel—of_the—boards featei^artrof-which-was-telcen-uvi^y--menibers-of:- Follow the "Mites of Smiles*' each Tuesday in the Record;- Every Lubrication Job Guaranteed to Give Satisfaction. "day rtightracceptednhTg-three^tracts of land owned follows: Three years, John J. -

1000 Freshmen Begin College Careers Here

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 10-1953 The Register, 1953-09&10-00 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1953-09&10-00" (1953). NCAT Student Newspapers. 129. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/129 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meet Me at Welcome Homecoming to all November 7 Freshmen 'The Cream of College News" VOL. XLVIX A. and T. College, Greensboro, N. C, Sept.-Oci., 1953 5 CENTS PER COPY 1000 FRESHMEN BEGIN COLLEGE CAREERS HERE Korean Vets Help TOPS LYCEUM Swell Enrollment GREENSBORO, N. C. — Miss By KENNETH KIRBY, '55 Margaret Tynes, leading soprano The office of the Registrar reveals with the New York City Opera that approximately 2,575 students en Company and a graduate of this rolled at A. and T. College during college, tops a list of outstanding the fall quarter registration. Of this artists to appear on the lyceum number, over 1,000 are freshmen. The series at A. and T. College for the final tabulations, however, have nol current school year. been completed. A native of Greensboro and The new students arrived at a time soloist with the famed A. -

Topical Weill: News and Events

Volume 29 Number 1 topical Weill Spring 2011 A supplement to the Kurt Weill Newsletter news & news events Mark Your Calendars! “Is it opera or musical? Formal definitions seem academic when confronted by a show of such passion and power . a show that deserves to be seen” (The Guardian). Street Scene won the Evening Standard Award for best musical on the London stage in 2008. This fall the Opera Group/Young Vic production, directed by John Fulljames, will return to the Young Vic’s South Bank theater on 15 September 2011, where it will play 14 times through 1 October, except for a two-day interval (25–26 September) during which the company will travel to Vienna’s Theater an der Wien for two performances. Keith Lockhart will conduct the BBC Concert Orchestra in London 15–20 September and in Vienna; in the other performances, the Southbank Sinfonia will be conducted by Tim Murray. Immediately following the London run, the production will tour the U.K., making stops in Basingstoke (3–4 October), Edinburgh (6–8 October), Newport (10–12 October), and Hull (13–15 October). Weill’s first opera, Der Protagonist, premiered at the Dresden State Opera in 1926. Eighty-five years later and sixty-five years after its creation for Broadway, Street Scene debuts at Dresden’s Semperoper, the first of Weill’s American works ever to be presented there. Street Scene opens on 19 June for a seven-performance run ending 3 July, in a production conducted by Jonathan Darlington and directed by Bettina Bruinier, with a cast including Sabine Brohm (Anna Maurrant), Markus Marquardt (Frank Maurrant), Carolina Ullrich (Rose), and Simeon Esper (Sam Kaplan). -

Singing African-American Spirituals: a Reflection on Racial Barriers In

451_486_JOS May_June05 Features 3/27/05 5:59 PM Page 451 Lourin Plant Singing African-American Spirituals: A Reflection on Racial Barriers in Classical Vocal Music tive communication across historic complex racial legacy, African- racial dividing lines. American spirituals provide positive Although the world enjoys African- means to that end. The path to under- American solo spirituals everywhere, standing our nation’s racial legacy American singers in the last half cen- passes through our shared joys, pains, tury have found fewer occasions to and sorrows, not by painfully forget- sing or record them. This may be due ting or fearfully ignoring them. in part to the troubled racial history Learning to love, teach, and especially of the American performing stage, to sing solo spirituals brings us closer especially in the shadow of blackface to humbly reconciling the truth of minstrelsy, and in the larger realm of what we are, together. a nation struggling mightily with its racial legacy. With race and spiritu- PART ONE— als in mind, I explore the subject for A CALL TO REFLECTION Lourin Plant solo singers in two parts. Part One explores a combination of elements: “. the problem of the Twentieth Century INTRODUCTION the barrier of race in solo spirituals; is the problem of the color-line.”1 (W. E. white discomfort with Negro dialect B. DuBois) America witnessed the passing of and the conjuring ghosts of blackface More than one hundred years after three leading late twentieth century minstrelsy; possible rebuke by some DuBois raised the veil on his prophetic exponents of the African-American African-Americans who believe The Souls of Black Folk (1903), his spiritual within seven months of each America’s largely unaddressed racial thoughtful statement remains a sen- other: William Warfield, solo artist/ history creates an atmosphere of dis- tinel of American racial history and educator; Eileen Southern, Harvard trust of whites who sing these sacred again calls the nation to reflection.