The Evolution of Eva Jessye's Programming As Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chanticleer Christmas 2018 Reader

A Chanticleer Christmas WHEN: VENUE: WEDNESDAY, MEMORIAL CHURCH DECEMBER 12, 2018 7∶30 PM Photo by Lisa Kohler Program A CHANTICLEER CHRISTMAS Cortez Mitchell, Gerrod Pagenkopf*, Kory Reid Alan Reinhardt, Logan Shields, Adam Ward, countertenor Brian Hinman*, Matthew Mazzola, Andrew Van Allsburg, tenor Andy Berry*, Zachary Burgess, Matthew Knickman, baritone and bass William Fred Scott, Music Director I. Corde natus ex parentis Plainsong Surge, illuminare Jerusalem Francesco Corteccia (1502–1571) Surge, illuminare Jerusalem Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594) II. Angelus ad pastores ait Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Quem vidistis, pastores dicite Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) Quem vidistis, pastores? Orlando di Lasso (1532–1594) D’où viens-tu, bergère? Trad. Canadian, arr. Mark Sirett Bring a Torch, Jeanette, Isabella Trad. French, arr. Alice Parker and Robert Shaw III. Nesciens mater Jean Mouton (1459–1522) O Maria super foeminas Orazio Vecchi (1550–1605) Ave regina coelorum Jacob Regnart (1540–1599) IV. Here, mid the Ass and Oxen Mild Trad. French, arr. Parker/Shaw O magnum mysterium+ Tomás Luis de Victoria (1548–1611) Behold, a Simple, Tender Babe Peter Bloesch (b. 1963) World Premier performances V. Hacia Belén va un borrico Trad. Spanish, arr. Parker/Shaw Staffan var en stalledräng Jaakko Mäntyjärvi (b. 1963) Commissioned in 2016 by Gayle and Timothy Ober, Allegro Fund of The Saint Paul Foundation, in honor of their 35th wedding anniversary. Chanticleer Trad. English, arr. Philip Wilder ¡Llega la Navidad! Ramón Díaz (1901–1976), arr. Juan Tony Guzmán —INTERMISSION— 2 VI. Ave Maria+ Franz Biebl (1906–2001) Bogoróditse Dyévo, ráduisya Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) VII. A selection of popular carols to be chosen from… Up! Good Christen Folk Trad. -

Philharmonic Au Dito R 1 U M

LUBOSHUTZ and NEMENOFF April 4, 1948 DRAPER and ADLER April 10, 1948 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN April 27, 1948 MENUHIN April 29, 1948 NELSON EDDY May 1, 1948 PHILHARMONIC AU DITO R 1 U M VOL. XLIV TENTH ISSUE Nos. 68 to 72 RUDOLF f No S® Beethoven: S°"^„passionala") Minor, Op. S’ ’e( MM.71l -SSsr0*“” « >"c Beethoven. h6tique") B1DÛ SAYÂO o»a>a°;'h"!™ »no. Celeb'“’ed °P” CoW»b» _ ------------------------- RUOOtf bKch . St«» --------------THE pWUde'Pw»®rc’^®®?ra Iren* W°s’ „„a olh.r,„. sr.oi «■ o'--d s,°3"' RUDOLF SERKIN >. among the scores of great artists who choose to record exclusively for COLUMBIA RECORDS Page One 1948 MEET THE ARTISTS 1949 /leJ'Uj.m&n, DeLuxe Selective Course Your Choice of 12 out of 18 $10 - $17 - $22 - $27 plus Tax (Subject to Change) HOROWITZ DEC. 7 HEIFETZ JAN. 11 SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT 1. ORICINAL DON COSSACK CHORUS & DANCERS, Jaroff, Director Tues. Nov. 1 6 2. ICOR CORIN, A Baritone with a thrilling voice and dynamic personality . Tues. Nov. 23 3. To be Announced Later 4. PATRICE MUNSEL......................................................................................................... Tues. Jan. IS Will again enchant us-by her beautiful voice and great personal charm. 5. MIKLOS GAFNI, Sensational Hungarian Tenor...................................................... Tues. Jan. 25 6. To be Announced Later 7. ROBERT CASADESUS, Master Pianist . Always a “Must”...............................Tues. Feb. 8 8. BLANCHE THEBOM, Voice . Beauty . Personality....................................Tues. Feb. 15 9. MARIAN ANDERSON, America’s Greatest Contralto................................. Sun. Mat. Feb. 27 10. RUDOLF FIRKUSNY..................................................................................................Tues. March 1 Whose most sensational success on Feb. 29 last, seated him firmly, according to verdict of audience and critics alike, among the few Master Pianists now living. -

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Title Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of mixed John W. Work 1952 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0110 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Go Tell it on the Mountain for chorus of women's John W. Work 1949 voices, three part 1121-113-001_0109 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals I Want Jesus to Walk with Me Edward Boatner 1949 1121-113-001_0028 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Heritage of Spirituals Lord, I'm out Here on Your Word for John W. Work 1952 unaccompanied mixed chorus 1121-113-001_0111 1121-113-001 Galaxy Music Corporation A Lincoln Letter Ulysses Kay 1958 1121-113-001_0185 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Like as a Father Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0188 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus O Praise the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0187 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation A New Song, Three Psalms for Chorus Sing Unto the Lord Ulysses Kay 1961 1121-113-001_0186 1121-113-001 C. F. Peters Corporation Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Title Added Description Contributor(s) Date(s) Item # Box Publisher Additional Notes A Wreath for Waits II. Lully, Lully Ulysses Kay 1956 1121-113-001_0189 1121-113-001 Associated Music Publishers Aeolian Choral Series King Jesus is A-Listening, negro folk song William L. -

Porgy and Bess» in Oltre Settant’Anni Di Interpretazioni DISCOGRAFIA SU «PORGY and BESS»

1 Giovinezza di «Porgy and Bess» in oltre settant’anni di interpretazioni DISCOGRAFIA SU «PORGY AND BESS» di Aloma Bardi [all’interno di ciascun capitolo, le voci sono elencate secondo l’ordine cronologico delle registrazioni] I. «PORGY AND BESS» NELL’INTERPRETAZIONE DI GEORGE GERSHWIN Gershwin performs Gershwin: Rare recordings, 1931-1935. Registr. dal vivo delle prove di una selezione dell’opera; 19 luglio 1935. Introduction – Summertime (Abbie Mitchell); A woman is a sometime thing (Edward Matthews); Atto I, Scena I, Finale; My man’s gone now (Ruby Elzy); Bess, you is my woman now (Todd Duncan, Anne Brown); George Gershwin, pf., dir. e annunciatore; 18:07; MusicMasters 5062-2-C, 1991. Testimonianza memorabile per respiro melodico, scelta dei tempi e ritegno antisentimentalistico risultanti dalla concezione sinfonica della direzione, che pone le voci nel fitto tessuto strumentale. II. INCISIONI DELL’OPERA In Porgy and Bess, la definizione di opera integrale e di versione definitiva è articolata e richiede una precisazione: l’edizione per voce e pf., l’unica stampata e pubblicamente disponibile (Warner Bros., 1935) non è una riduzione della partitura orchestrale, bensì testimonia la fase precedente a quella dell’orchestrazione ed è legata agli abbozzi manoscritti; Gershwin orchestrò l’opera mentre tale ed. era già in stampa. Il testo definitivo è invece convenzionalmente – e discutibilmente – considerato quello stabilito durante le rappresentazioni del debutto a Broadway, risultante da tagli numerosi e talora estesi, per lo più effettuati allo scopo di abbreviare la durata dello spettacolo e di eliminare difficoltà per gli interpreti o complessità ritenute eccessive in quel particolare contesto. Porgy and Bess. -

Proquest Dissertations

Leonard de Paur's arrangements of spirituals, work songs, and African songs as contributions to choral music: A black choral musician in the mid-twentieth century Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Woods, Timothy Erickson, 1958- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 18:42:48 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/282726 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

A Conductor's Guide to Twentieth-Century Choral-Orchestral Works in English

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9314580 A conductor's guide to twentieth-century choral-orchestral works in English Green, Jonathan David, D.M.A. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2009 Music for the (American) People: The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964 Jonathan Stern The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2239 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE CONCERTS AT LEWISOHN STADIUM, 1922-1964 by JONATHAN STERN VOLUME I A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2009 ©2009 JONATHAN STERN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Ora Frishberg Saloman Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan Date Executive Officer Professor Stephen Blum Professor John Graziano Professor Bruce Saylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE LEWISOHN STADIUM CONCERTS, 1922-1964 by Jonathan Stern Adviser: Professor John Graziano Not long after construction began for an athletic field at City College of New York, school officials conceived the idea of that same field serving as an outdoor concert hall during the summer months. The result, Lewisohn Stadium, named after its principal benefactor, Adolph Lewisohn, and modeled much along the lines of an ancient Roman coliseum, became that and much more. -

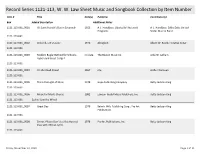

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number

Record Series 1121-113, W. W. Law Sheet Music and Songbook Collection by Item Number Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0001 It's Saint Patrick's Day in Savannah 1953 A. J. Handiboe; Liberty Bell Network A. J. Handiboe; Eddie Daly; United Programs States Marine Band 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0002 Beloved, Let Us Love 1976 Abingdon Albert W. Ream; Horatius Bonar 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0003 Modern Bugle Method for Schools, no date The Boston Music Co. Arlie W. Latham Legion and Scout Corps 1 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0004 On the Road Ahead 1967 n/a Arthur Donovan 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0005 This Little Light of Mine 1978 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0006 Music for Men's Chorus 1982 Lawson-Gould Music Publishers, Inc. Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 Ezekiel Saw the Wheel 1121-113-001_0007 Great Day 1976 Belwin Mills Publishing Corp.; Pro Art Betty Jackson King Publications 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0008 Sinner, Please Don't Let this Harvest 1978 Pro Art Publications, Inc. Betty Jackson King Pass with African Lyrics 1121-113-001 Friday, November 13, 2020 Page 1 of 31 Item # Title Date(s) Publisher Contributor(s) Box Added Description Additional Notes 1121-113-001_0009 Marks Choral Library 1973 Edward B. Marks Music Corporation; Belwin Betty Jackson King Mills Publishing Corp. 1121-113-001 I Want God's Heaven to be Mine 1121-113-001_0010 Stand the Storm 1980 Hope Publishing Company Betty Jackson King 1121-113-001 1121-113-001_0011a God is a God! 1983 Mar-Vel Betty Jackson King; Roland M. -

For Sewer Investigation

.^ c .w;.v.;^u.'u^v:^ RAHWAY RECORD, TUESDAY, JUNE 10,1930 WfeATHER /oitECAST ; , ; ' PUBL.I8HED Today: Cloudy, illghtly warmer. TV/ICE WEEKLY Tomorrow: F»|r, not much change In ttmper«tUT0. IN RAHWAY'S INTEpE8T8 '• The New Jersey Advocate Announcing Absorbing Tht Rahyyay Newa-Hcrald, the successor of the Union Democrat, Established 1840 ANOTHER VOL. XIX. SERIAL NO. 2152 Sixteen Pages PRICE THREE CENTS ] Mi RAHWAY, UNION CflUNTY, N! J., FRIDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 13,1930 WILL GfeAdUAtE WITH HIGHEST-HONORS r ''''.>".•.5": PROPERTY FOR PARK Corner Lake Avenue and St. George ^Avenue. FOR SEWER INVESTIGATION Tracts of Land, Including SquUr THE MANAGEMENT OF - idfD Ordinance PassedUAfter-Long Mt&cusswn iou.nl of Adjustment By Councilman andr-Gitizens-t-Engineer- A BoafoV of Adjustment to Questioned oh Workmanship carry out the provisions of the The same prompt and courteous treatment will be given, as tbat which has made our Station at Milton Avenue and Irving Street a success. LAND IN SQUIER FAMILY 151 YEARS zoning ordinance which was re- cently passed for this city, -was .appointed-by Mayor Adolph Ul- MONEY FOR CITIZENS' COMMITTEE brlch and announced at the Upohtherecomm^datiohofMayor^lolpfrui= meeting of the. Common Ooun- brich,'the Common Council at its meeting Wedne^ .cILWednesday night.' :_'_ . At the conclusion of a two-hour discussion, the. —The—personnel—of_the—boards featei^artrof-which-was-telcen-uvi^y--menibers-of:- Follow the "Mites of Smiles*' each Tuesday in the Record;- Every Lubrication Job Guaranteed to Give Satisfaction. "day rtightracceptednhTg-three^tracts of land owned follows: Three years, John J. -

Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Spring 5-15-2020 Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star Caleb Taylor Boyd Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Music Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Caleb Taylor, "Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star" (2020). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 2169. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/2169 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Todd Decker, Chair Ben Duane Howard Pollack Alexander Stefaniak Gaylyn Studlar Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star by Caleb T. Boyd A dissertation presented to The Graduate School of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 St. Louis, Missouri © 2020, Caleb T. Boyd Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................ -

112 Kansas History Western University at Quindaro and Its Legacy of Music by Paul Wenske

Promotional material, Jackson Jubilee Singers, Western University. Courtesy of Redpath Chautauqua Collection, University of Iowa Libraries, Iowa City, Iowa. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 42 (Summer 2019): 112–123 112 Kansas History Western University at Quindaro and Its Legacy of Music by Paul Wenske very seat in the Wausau, Wisconsin, Methodist church was filled on a fall October night in 1924 as the Jackson Jubilee Singers from Western University in distant Quindaro, Kansas, completed their last encore of spirituals. The next day, the Wausau Record-Herald enthused that the performance was “one of the most enjoyable concerts of the year” and that the enthralled audience “testified its approval by appreciative applause.”1 Today one might ask, who were the Jackson Jubilee Singers and where is—or was—Western University? But between 1903 and E1931, as African Americans sought to secure a place in American culture barely two generations after slavery, the Jackson Jubilee Singers were immensely popular. They toured the United States and Canada on the old Redpath-Horner Chautauqua circuit, promoting Western University, whose buildings graced the bluffs of the Missouri River in what is now a neighborhood in north Kansas City, Kansas. In fact, for a brief but significant period, the Jackson Jubilee Singers were the very face of Western University. Their talent, discipline, and professionalism raised awareness of and aided recruitment for the oldest African American school west of the Mississippi River and the best in the Midwest for musical training. “So great was their success in render- ing spirituals and the advertising of the music department of Western University that all young people who had any type of musical ambition decided to go to Western University at Quindaro,” wrote historian and Western alumnus Orrin McKinley Murray Sr.2 Despite its promising start, Western’s success was fleeting, and it closed in 1943. -

1000 Freshmen Begin College Careers Here

North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship NCAT Student Newspapers Digital Collections 10-1953 The Register, 1953-09&10-00 North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister Recommended Citation North Carolina Agricutural and Technical State University, "The Register, 1953-09&10-00" (1953). NCAT Student Newspapers. 129. https://digital.library.ncat.edu/atregister/129 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collections at Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in NCAT Student Newspapers by an authorized administrator of Aggie Digital Collections and Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Meet Me at Welcome Homecoming to all November 7 Freshmen 'The Cream of College News" VOL. XLVIX A. and T. College, Greensboro, N. C, Sept.-Oci., 1953 5 CENTS PER COPY 1000 FRESHMEN BEGIN COLLEGE CAREERS HERE Korean Vets Help TOPS LYCEUM Swell Enrollment GREENSBORO, N. C. — Miss By KENNETH KIRBY, '55 Margaret Tynes, leading soprano The office of the Registrar reveals with the New York City Opera that approximately 2,575 students en Company and a graduate of this rolled at A. and T. College during college, tops a list of outstanding the fall quarter registration. Of this artists to appear on the lyceum number, over 1,000 are freshmen. The series at A. and T. College for the final tabulations, however, have nol current school year. been completed. A native of Greensboro and The new students arrived at a time soloist with the famed A.