Oscar Levant: Pianist, Gershwinite, Middlebrow Media Star

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

The Leadership Issue

SUMMER 2017 NON PROFIT ORG. U.S. POSTAGE PAID ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL connections BALTIMORE, MD 5204 Roland Avenue THE MAGAZINE OF ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL Baltimore, MD 21210 PERMIT NO. 3621 connections THE ROLAND PARK COUNTRY SCHOOL COUNTRY PARK ROLAND SUMMER 2017 LEADERSHIP ISSUE connections ROLAND AVE. TO WALL ST. PAGE 6 INNOVATION MASTER PAGE 12 WE ARE THE ROSES PAGE 16 ADENA TESTA FRIEDMAN, 1987 FROM THE HEAD OF SCHOOL Dear Roland Park Country School Community, Leadership. A cornerstone of our programming here at Roland Park Country School. Since we feel so passionately about this topic we thought it was fitting to commence our first themed issue of Connections around this important facet of our connections teaching and learning environment. In all divisions and across all ages here at Roland Park Country School — and life beyond From Roland Avenue to Wall Street graduation — leadership is one of the connecting, lasting 06 President and CEO of Nasdaq, Adena Testa Friedman, 1987 themes that spans the past, present, and future lives of our (cover) reflects on her time at RPCS community members. Joe LePain, Innovation Master The range of leadership experiences reflected in this issue of Get to know our new Director of Information and Innovation Connections indicates a key understanding we have about the 12 education we provide at RPCS: we are intentional about how we create leadership opportunities for our students of today — and We Are The Roses for the ever-changing world of tomorrow. We want our students 16 20 years. 163 Roses. One Dance. to have the skills they need to be successful in the future. -

The “Advertiser” Stands for the Best Interests of Belmar

Library, Public The “Advertiser” Stands for the Best Interests of Belmar BOTH CtfHXHK Vol. XXV. No. 27, Whole No. 1981. BELMAR, N. J., FRIDAY, JULY 6, 1917. Single Copy Three Cents BOOMING BELMAR F. P. Philbrick FAMOUS MUSICIAN HERE Guests at Belmar’s COUNTY BANKS ISSUE STATEMENTS Work Being Done by the Miller- Eugene Bernstein is a Summer Res Margerum Co., Trenton. Passes Away ident of Belmar. Ever Popular Hotels Thirty Institutions in Monmouth County Show Increase of The tract of land that belonged to One of the distinguished summer the David H. Wilson estate, located HAD BEEN IN DRUG BUSINESS IN residents of Belmar is a famous mu HOLIDAY BRINGS MANY PEOPLE on our Main street at the corner of BELMAR 40 YEARS sician, Eugene Bernstein. Mr. Bern TO THE SHORE $3,700,000 in a Year. New Bedford road, Belmar, was re stein and his family came to Belmar cently purchased by that enterpris One of New Jersey’s Best Known last week for their second season Columbia Hotel Opening Dinner is 1916, but on that date this year the During the past week the thirty ing land development firm, the Mil- Pharmacists—Had Wide Circle of and are occupying .the Sanford Attended by About Two Hundred banks of Monmouth county have pub deposits had increased to an amount ler-Margerum Company, 150 East house, Twelfth avenue and River exceeding that of a year ago. Acquaintances. People. lished linancial statements. These State street, Trenton. road. Mr. Bernstein is very much E. F. Lyman, Jr., who assumed the They are now grading through please with Belmar and says that statements were called for on June Frank P. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

The Harlem Renaissance: a Handbook

.1,::! THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF ARTS IN HUMANITIES BY ELLA 0. WILLIAMS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES ATLANTA, GEORGIA JULY 1987 3 ABSTRACT HUMANITIES WILLIAMS, ELLA 0. M.A. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY, 1957 THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE: A HANDBOOK Advisor: Professor Richard A. Long Dissertation dated July, 1987 The object of this study is to help instructors articulate and communicate the value of the arts created during the Harlem Renaissance. It focuses on earlier events such as W. E. B. Du Bois’ editorship of The Crisis and some follow-up of major discussions beyond the period. The handbook also investigates and compiles a large segment of scholarship devoted to the historical and cultural activities of the Harlem Renaissance (1910—1940). The study discusses the “New Negro” and the use of the term. The men who lived and wrote during the era identified themselves as intellectuals and called the rapid growth of literary talent the “Harlem Renaissance.” Alain Locke’s The New Negro (1925) and James Weldon Johnson’s Black Manhattan (1930) documented the activities of the intellectuals as they lived through the era and as they themselves were developing the history of Afro-American culture. Theatre, music and drama flourished, but in the fields of prose and poetry names such as Jean Toomer, Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen and Zora Neale Hurston typify the Harlem Renaissance movement. (C) 1987 Ella 0. Williams All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special recognition must be given to several individuals whose assistance was invaluable to the presentation of this study. -

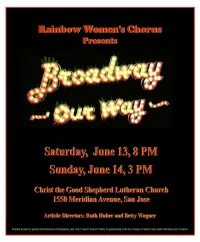

Broadway-Our-Way-2015.Pdf

Our Mission Rainbow Women’s Chorus works together to develop musical excellence in an atmosphere of mutual support and respect. We perform publicly for the entertainment, education and cultural enrichment of our audiences and community. We sing to enhance the esteem of all women, to celebrate diversity, to promote peace and freedom, and to touch people’s hearts and lives. Our Story Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a nonprofit corporation governed by the Action Circle, a group of women dedicated to realizing the organization’s mission. Chorus members began singing together in 1996, presenting concerts in venues such as Christ the Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Le Petit Trianon Theatre, the San Jose Repertory Theater and Triton Museum. The chorus also performs at church services, diversity celebrations, awards ceremonies, community meetings and private events. Rainbow Women’s Chorus is a member of the Gay and Lesbian Association of Choruses (GALA). In 2000, RWC proudly co-hosted GALA Festival in San Jose, with the Silicon Valley Gay Men’s Chorus. Since then, RWC has participated in GALA Festivals in Montreal (2004), Miami (2008), and Denver (2012). In February 2006, members of RWC sang at Carnegie Hall in NYC with a dozen other choruses for a breast cancer and HIV benefit. In July 2010, RWC traveled to Chicago for the Sister Singers Women’s Choral Festival. But we like it best when we are here at home, singing for you! Support the Arts Rainbow Women’s Chorus and other arts organizations receive much valued support from Silicon Valley Creates, not only in grants, but also in training, guidance, marketing, fundraising, and more. -

Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health: a Global Perspective

Chapter 12 Smokeless Tobacco Use in the African Region 353 Blank page. Smokeless Tobacco and Public Health: A Global Perspective Chapter Contents Description of the Region ........................................................................................................................357 Prevalence of Smokeless Tobacco Use....................................................................................................358 Types of Products and Patterns of Use ....................................................................................................362 Toxicity and Nicotine Profiles .................................................................................................................365 Health Problems Associated With Product Use.......................................................................................365 Marketing and Production Practices of Industry .....................................................................................367 Production ..........................................................................................................................................367 Distribution ........................................................................................................................................367 Marketing ...........................................................................................................................................368 Current Policy and Interventions .............................................................................................................369 -

The Evolution of Eva Jessye's Programming As Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982

The Evolution of Eva Jessye's Programming as Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982 Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Jenkins, Lynnel Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 25/09/2021 23:30:45 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/622962 THE EVOLUTION OF EVA JESSYE’S PROGRAMMING AS EVIDENCED IN HER CHORAL CONCERT PROGRAMS FROM 1927-1982 by Lynnel Jenkins __________________________ Copyright © Lynnel Jenkins 2016 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2016 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Lynnel Jenkins, titled The Evolution of Eva Jessye’s Programming as Evidenced in Her Choral Concert Programs from 1927-1982 and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree. ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 Bruce Chamberlain ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 Elizabeth Schauer ________________________________________________ Date: 10/14/16 John Brobeck Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Philharmonic Au Dito R 1 U M

LUBOSHUTZ and NEMENOFF April 4, 1948 DRAPER and ADLER April 10, 1948 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN April 27, 1948 MENUHIN April 29, 1948 NELSON EDDY May 1, 1948 PHILHARMONIC AU DITO R 1 U M VOL. XLIV TENTH ISSUE Nos. 68 to 72 RUDOLF f No S® Beethoven: S°"^„passionala") Minor, Op. S’ ’e( MM.71l -SSsr0*“” « >"c Beethoven. h6tique") B1DÛ SAYÂO o»a>a°;'h"!™ »no. Celeb'“’ed °P” CoW»b» _ ------------------------- RUOOtf bKch . St«» --------------THE pWUde'Pw»®rc’^®®?ra Iren* W°s’ „„a olh.r,„. sr.oi «■ o'--d s,°3"' RUDOLF SERKIN >. among the scores of great artists who choose to record exclusively for COLUMBIA RECORDS Page One 1948 MEET THE ARTISTS 1949 /leJ'Uj.m&n, DeLuxe Selective Course Your Choice of 12 out of 18 $10 - $17 - $22 - $27 plus Tax (Subject to Change) HOROWITZ DEC. 7 HEIFETZ JAN. 11 SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT 1. ORICINAL DON COSSACK CHORUS & DANCERS, Jaroff, Director Tues. Nov. 1 6 2. ICOR CORIN, A Baritone with a thrilling voice and dynamic personality . Tues. Nov. 23 3. To be Announced Later 4. PATRICE MUNSEL......................................................................................................... Tues. Jan. IS Will again enchant us-by her beautiful voice and great personal charm. 5. MIKLOS GAFNI, Sensational Hungarian Tenor...................................................... Tues. Jan. 25 6. To be Announced Later 7. ROBERT CASADESUS, Master Pianist . Always a “Must”...............................Tues. Feb. 8 8. BLANCHE THEBOM, Voice . Beauty . Personality....................................Tues. Feb. 15 9. MARIAN ANDERSON, America’s Greatest Contralto................................. Sun. Mat. Feb. 27 10. RUDOLF FIRKUSNY..................................................................................................Tues. March 1 Whose most sensational success on Feb. 29 last, seated him firmly, according to verdict of audience and critics alike, among the few Master Pianists now living.