The Illustrated Baburnama

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baburnama Bangla Pdf

Baburnama bangla pdf Continue literally: The Story of Babur or Letters of Babur; as ,' ;ﻧﺎﻣ :Supported by WBEIDC Ltd., supported by SSTIS Technologies Pvt Ltd Memoirs Babur, founder of the Mughal Empire Awards Ceremony at the court of Sultan Ibraham, before being sent on an expedition to Sambhal Beburnama (Chagatai /Persian an alternative known as Tuzk-e-Babri) - a memoir of the Ẓahīr-ud-Dev Muhammad Babur (1483-1530), the empire of the founder of the Great Moguls and great-grandson Timur. It is written in Chagatai language, known to Baburu as Turks (meaning Turkic), the colloquial language of asijan-timurids. During the reign of Emperor Akbar, the work was fully translated into Persian, the usual literary language at the court of the Mughals, the court of the Mughals, Abdul Rahim, in 998 AD (1589-1590). Translations into many other languages followed, mostly from the 19th century. Babur was educated by Prince Timurid, and his observations and comments in his memoirs reflect an interest in nature, society, politics and economics. His vivid account of events covers not only his own life, but also the history and geography of the areas in which he lived, as well as the people with whom he came into contact. The book covers such diverse topics as astronomy, geography, state craft, military issues, weapons and battles, plants and animals, biographies and family chronicles, courtiers and artists, poetry, music and paintings, wine parties, historical monuments tours, and reflections on human nature. Although Babur himself did not appear to have ordered any illustrated versions, his grandson began as soon as he was presented with a finished Persian translation in November 1589. -

Historiography of Mughal Period-An Analytical Study

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-6, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Historiography of Mughal Period-An Analytical Study Dr. Shahina Bano Department Of History, Assistant Professor, Maharni’s Arts College For Women-Bangalore-1 Abstract: In the Mughal period an innovative class Moghul Empire and great grandson of Timur. It is of historiography- that of official histories or an autobiographical work.It was originally written namah- came in to vogue in india under Persian in the Chagatai language, known to baburas influence.Akbar introduced the practice of “Turk”(meaning Turkic), the spoken language of commissioning officials or others to write the the Andijan-Timurids. Babur’s prose is highly history of his new empire giving them access for Persianised in its sentences structure, morphology, this purpose to state records.This practice and language. It is also contains many pharases and continued down to the reign of Aurangzeb who, smaller poems in Persian.During the Emperor’s however, stopped it in his eleventh regnal reign, the work was completely translated to year.Besides,, such official histories, biographical Persian by a Moghul courtier, Abdul Rahim, in works great historical interst were also produced (1589-90) during the period under survey. And we not entirely dependent upon chroniclers; we have in some Baburnamah can be divided into three Parts. The instances contemporary, independent historians. first part begins with his accession to the throne of The historians of the Mughal Period did not Fargana and ends with his driving out from his develop any philosophy of history from which flight to his last invasion of lndia. -

Francesca Galloway

FRANCESCA GALLOWAY INDIAN PAINTINGS 1450 -1850 Catalogue by JP Losty 11th June - 20th July 2018 It is our great pleasure to introduce this group, rich in the coming year is to be decided by God. It is per- in early Mughal and pre-Mughal paintings, many of haps telling that so much of the energy of the Mughal which come from an important private collection. art of this period (the mid-18th century), when the Among this group are three folios from the first il- empire is beginning to decentralize and to decline lustrated Baburnama (cat. 5 – 7) (also known as the politically and economically, can be seen to go into V&A Baburnama), an extraordinary memoir de- the lavish detailing of courtly celebration. This is tailing the nomadic life of the Central Asian prince reflected here in the sumptuous display of conspicu- Babur, displaced from his home and in search of ous wealth, with intricately illustrated fireworks and a kingdom fit for his Timurid ancestry – an ambi- hanging lakeside lanterns, a gaudy elephant-shaped tion realised at last with his conquest of Delhi and candelabra and attending musicians, in a scene full of founding of the Mughal empire. This particular copy opulent costumes, jewels and sweetmeats. was an important event in itself, commissioned by Babur’s grandson Akbar and translated into Persian There are several fine and characterful Pahari paint- for the first time in the 1580s. In a sense this was a ings. Cat. 20 sees Raja Mahendra Pal of Basohli political act, an illustrated manuscript to enact the setting out for an expedition with his man ladies. -

King of the Birds

KING OF THE BIRDS Print of a peacock. Catherine Hettler. SPRING 2020 50 KRISTEN HICKEY KING OF THE BIRDS: MAKING SYMBOL, SUBJECT, AND SCIENCE IN THE SKIES OF HINDUSTAN When the Mughals founded an empire in Hindustan, they sought to legitimize their budding dynasty through diverse sources of power. In the texts and art produced by emperors and their courts during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, these performances of power constantly featured birds. Birds, enfleshed and imagined, were used as motifs that positioned the Mughals as the cultural descendants of a long Islamic tradition of storytelling and spirituality. Wild and captive birds became an extension of the imperial court as emperors strove to model the legendary rule of King Solomon, who was renowned for his just power over all creatures. During this age of scientist-kings, avians also became catalysts for experimentation and the production of knowledge. This intricate relationship between birds and power reveals a Mughal conception of empire, defined by fluid boundaries between the human and animal kingdoms. Kristen Hickey Written for Ruling Hindustan (HIST 494) Dr. Lisa Balabanlilar In the Hindustani empire of the Mughals, birds were companions, partners in the hunt, playthings, and sources of great entertainment. They were fascinating airborne creatures, worthy of great scientific attention. The subject of unimaginable hours of artistic labor, they appeared in countless folios, with their feathers adorning the jeweled turbans of only the most powerful emperors.1 The presence of birds illuminated and defined the seat of the Mughal emperor as a ruler in an ancient tradition of powerful kingships. -

Five Travelers by Nishant Batsha

Five Travelers by Nishant Batsha he history of India is in many ways a history of travelers. Some of these travelers came aboard tall-masted ships in the name of trade. Others arrived prepared for battle, with weaponry and T armies that stretched behind them for miles. And still others, like the artist Jan Serr, came to be inspired by a subcontinent so different and so unlike any other place. Truthfully, prior to the conveniences of modern travel, most visitors to India came as a mix, or as a result, of other categories. The curious could only come as a result of the conqueror. The conqueror carried with him a healthy amount of curiosity. The relationship between travel and event is so enmeshed that it becomes possible to pick four travelers and through them, find a history of India. Al-Bīrūnī “We must form an adequate idea of that which renders it so particularly difficult to penetrate to the essential nature of any Indian subject. First, they differ from us in everything which other nations have in common.” (Al-Bīrūnī, Alberuni’s India, 17). In the early eleventh century, Abū al-Rayhān Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Bīrūnī (973–1048), commonly known as Al-Bīrūnī, sat down and wrote a history of India. He did so after watching, in horror, the pillaging of the country. Al-Bīrūnī was born in 973 in Khwarezm, near modern-day Khiva in Uzbekistan. His birth coincided with the nadir of the Samanid Empire, an empire that had made Bukhara and Samarkand—and to a lesser extent, Khwarezm—areas of intense learning in the arts, sciences, and humanities. -

Sources on Timurid History and Art

A Century of Princes Sources on Timurid History-and Art -- -- -- --- ---- -- ---- - -- --------- -- -- -.: -=..::. ----- Selected and Translated by W. M. Thackston ------------ --- ~-=- ---=-=- A CENTURY OF PRINCES "Bibi Khanim" Mosque, Samarqand. Peter M. Brenner © 1988. A Century of Prince~/ Sources on Timurid History and Art Selected and Translated by w. M. Thackston * Published in Conjunction with the Exhibition "Timur and the Princely Vision," Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, 1989 * The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture Cambridge, Massachusetts 1989 · - n -_I ,I The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at HarvardUniversity and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Copyright © 1989 M.I.T. LIBRARIES ISBN 0-922673-11-X JUN 2 198~ RECEIVED as.=-- __ .\ Contents MAPS vii GENEALOGICAL CHARTS x INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND HISTORIOGRAPHY History: Retrospective on the Timurid Years Mir Dawlatshah Samarqandi's Tadhkirat al-shu'ara ll Sharafuddin Ali Yazdi's Zafarnama 63 Khwandamir's Habib al-siyar l01 Synopsis of the House of Timur 237 Autobiography: From Within the Ruling House Babur Mirza's Baburnama: A Visit to Herat.. 247 Observations of the Outside Ghiyathuddin Naqqash's Report on a Timurid Mission to China 279 Kamaluddin Abdul-Razzaq Samarqandi's Mission to Calicut and Vijayanagar 299 THE ARTS Artistic Production Arzadasht 323 Miscellaneous Documents 329 Calligraphers and Artists -\ Dost-Muhammad's Introduction to the Bahram Mirza Album 335 Malik Daylami's Introduction to the Amir Husayn Beg Album 351 v CONTENTS Mir Sayyid-Ahmad's Introduction to the Amir Ghayb Beg Album 353 Mirza Muhammad-Haydar Dughlat's Tarikh-i Rashidi 357 Literary Conceits: Self-Images Sultan-Husayn Mirza's "Apologia" 363 Mir Ali-Sher Nawa'i's Preface to His First Divan .373 GLOSSARY OF TI1l.ES AND TERMS ..........................•....•......•...................................... -

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605

Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, 1500 - 1605 A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrew de la Garza Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor; Stephen Dale; Jennifer Siegel Copyright by Andrew de la Garza 2010 Abstract This doctoral dissertation, Mughals at War: Babur, Akbar and the Indian Military Revolution, examines the transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. It emphasizes the practical specifics of how the Imperial army waged war and prepared for war—technology, tactics, operations, training and logistics. These are topics poorly covered in the existing Mughal historiography, which primarily addresses military affairs through their background and context— cultural, political and economic. I argue that events in India during this period in many ways paralleled the early stages of the ongoing “Military Revolution” in early modern Europe. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. ii Dedication This document is dedicated to John Nira. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my advisor, Professor John F. Guilmartin and the other members of my committee, Professors Stephen Dale and Jennifer Siegel, for their invaluable advice and assistance. I am also grateful to the many other colleagues, both faculty and graduate students, who helped me in so many ways during this long, challenging process. -

12 Review of Literature on Variability of Various Characteristics of Mughal Period (1707-1857) Dr. Jayveer Singh and Mrs. Pushpl

Review Of Literature On Variability Of Various Characteristics Of Mughal Period (1707-1857) Dr. Jayveer Singh and Mrs. Pushplata Chaturvedi *Associate Professor, Department of History, OPJS University, Churu, Rajasthan (India) **Research Scholar, Department of History, OPJS University, Churu, Rajasthan (India) e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Mughal Empire at its zenith commanded resources unprecedented in Indian history and covered almost the entire subcontinent. From 1556 to 1707, during the heyday of its fabulous wealth and glory, the Mughal Empire was a fairly efficient and centralized organization, with a vast complex of personnel, money, and information dedicated to the service of the emperor and his nobility. Much of the empire’s expansion during that period was attributable to India’s growing commercial and cultural contact with the outside world. The 16th and 17th centuries brought the establishment and expansion of European and non-European trading organizations in the subcontinent, principally for the procurement of Indian goods in demand abroad. Indian regions drew close to each other by means of an enhanced overland and coastal trading network, significantly augmenting the internal surplus of precious metals. With expanded connections to the wider world came also new ideologies and technologies to challenge and enrich the imperial edifice. [Singh, J. and Chaturvedi, P. Review Of Literature On Variability Of Various Characteristics Of Mughal Period (1707-1857). Academ Arena 2020;12(8):12-23]. ISSN 1553-992X (print); ISSN 2158-771X (online). http://www.sciencepub.net/academia. 4. doi:10.7537/marsaaj120820.04. Keywords: Review Of Literature, Variability, Characteristics, Mughal Period (1707-1857) Introduction: depicting vividly a systematic historical treatment of For the study of this kind in hand, factual this region through different periods. -

Babur`S Contributions to Understanding and Development of Linkages Between Central and South Asia

Zahid Anwar BABUR’S CONTRIBUTIONS TO UNDERSTANDING AND DEVELOPMENT OF LINKAGES BETWEEN CENTRAL AND SOUTH ASIA It is an interesting study to explore linkages between Central and South Asia in historical perspective. This piece of research digs out the impact of increased linkages on the people of the two regions. Central and South Asian Regions have geographical, ethnic, historical and cultural connections. Natural and human geography played a significant role in the transfer of ideas and goods between the Central and South Asia. From time immemorial important personalities and crucial events have affected these linkages. Maurya, Kushan, Greek, Hindushahi, Mongol, Timurid and Mughul dynasties influenced the developments in Central Asia and South Asia. Zahiruddin Mohammad Babur defeated Ibrahim Lodhi of the Indian Lodhi dynasty in the battle of Panipat in 1526 and founded Mughal Empire and influenced to a great extent the war technology in the subcontinent. Babur is credited with introducing cannons in warfare when he invaded India. During the 1st Battle of Panipat, he has about fifteen thousand soldiers and many cannons. Ibrahim Lodi the Sultan of Delhi on the other hand had about forty thousand troops and hundred war elephants. Babur is said to have used his cannons to good effect. The success and the new developments in its wake facilitated the flow of ideas and natural resources and goods between South and Central Asian Areas. This paper explores the development of linkages in the aftermath of Babar`s Indian expeditions. It will be useful to know Babur`s Central Asian pedigree and understand the origins of Indian Mughal Empire in a new perspective. -

The Timurid Legacy: a Reaffirmation and a Reassessment

Cahiers d’Asie centrale 3/4 | 1997 L’héritage timouride : Iran – Asie centrale – Inde, XVe- XVIIIe siècles The Timurid Legacy: A Reaffirmation and a Reassessment Maria Eva Subtelny Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/462 ISSN: 2075-5325 Publisher Éditions De Boccard Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 1997 Number of pages: 9-19 ISBN: 2-85744-955-0 ISSN: 1270-9247 Electronic reference Maria Eva Subtelny, « The Timurid Legacy: A Reaffirmation and a Reassessment », Cahiers d’Asie centrale [Online], 3/4 | 1997, Online since 03 January 2011, connection on 14 November 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/asiecentrale/462 © Tous droits réservés The Timurid Legacy : A Reaffirmation and a Reassessment Maria Eva Subtelny The Timurids have universally been acknowledged by medieval Islamic cultural historians as representing the pinnacle of patronage of the arts and letters, notably poetry, calligraphy, painting and manuscript illumination, as well as architecture. They also patronized entire areas that are just beginning to come to light with new research and that further underscore the important role that this dynasty of Turko-Mongolian origin played in the cultural history of the eastern Islamic world. The entire proceedings of this conference are, in fact, devoted to the “legacy” of the Timurids, the impact of which was entirely out of proportion both to this dynasty’s geographical scope and to the relatively short length of its political rule (certainly when compared with such long-lived dynastic states as those of the Safavids, Ottomans and Mughals). We might ask ourselves whether the significance of the Timurid legacy results from the intrinsic extraordinariness of the Timurid per- iod or from the extraordinary richness of the sources available to scholars for its study. -

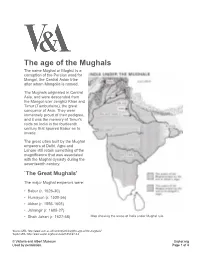

The Age of the Mughals the Name Mughal Or Moghul Is a Corruption of the Persian Word for Mongol, the Central Asian Tribe After Whom Mongolia Is Named

The age of the Mughals The name Mughal or Moghul is a corruption of the Persian word for Mongol, the Central Asian tribe after whom Mongolia is named. The Mughals originated in Central Asia, and were descended from the Mongol ruler Jenghiz Khan and Timur (Tamburlaine), the great conqueror of Asia. They were immensely proud of their pedigree, and it was the memory of Timur's raids on India in the fourteenth century that spurred Babur on to invade. The great cities built by the Mughal emperors at Delhi, Agra and Lahore still retain something of the magnificence that was associated with the Mughal dynasty during the seventeenth century. `The Great Mughals' The major Mughal emperors were: • Babur (r. 1526-30) • Humayun (r. 1530-56) • Akbar (r. 1556-1605) • Jahangir (r. 1605-27) • Shah Jahan (r. 1627-58) Map showing the areas of India under Mughal rule. Source URL: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/the-age-of-the-mughals/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth305/#1.4.2 © Victoria and Albert Museum Saylor.org Used by permission. Page 1 of 4 Aurangzeb (r. 1658-1707) Portrait of Babur, unknown artist, Around 1630, Museum no. IS.37-1972. Portrait of Mughal Emperor Zahir ud-Din Mohammad a.k.a.Babur (1483 - 1530), who reigned from 1526 - 30, from an album of paintings & calligraphy. Babur , the first Mughal emperor, was born in present-day Uzbekistan, and became ruler of Kabul in Afghanistan. From there, he invaded the kingdom of the Lodi Afghans in northern India in 1526 and established a dynasty that was to rule for three centuries. -

Osu1179937403.Pdf (2.74

THE LORDS OF THE AUSPICIOUS CONJUNCTION: TURCO-MONGOL IMPERIAL IDENTITY ON THE SUBCONTINENT A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lisa Ann Balabanlilar, M.A. ****** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Stephen Dale, Advisor Professor Jane Hathaway ____________________________ Professor Geoffrey Parker Advisor Graduate Program in History Copyright by Lisa Ann Balabanlilar 2007 ABSTRACT Contemporary studies of the Mughal dynasty in India have long been dominated by nationalist, sectarian and ideological agendas which typically present the empire of the Mughal as an exclusively Indian phenomenon, politically and culturally isolated on the sub- continent. Cross disciplinary scholarship on the Middle East and Islamic Central Asia assigns to the Mughals a position on the periphery. Omitting reference to a Central Asian legacy, scholars instead link the Mughals to the preceding nearly one thousand years of Muslim colonization in India. Yet to insist on a thousand years of Muslim continuity in India is to ignore the varied religious, cultural, and political traditions which were transmitted to the subcontinent by a widely diverse succession of immigrant communities. This study radically re-evaluates the scholarly and intellectual isolation with which the Mughals have been traditionally treated, and argues that the Mughals must be recognized as the primary inheritors of the Central Asian Turco- Persian legacy of their ancestor Timur (known in the West as Tamerlane). Driven from their homeland in Central Asia, the Timurid refugee community of South Asia meticulously maintained and asserted the universally admired charisma of their imperial lineage and inherited cultural ii personality.