Fatal Journeys 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Child Soldier

WAR PHOTO LIMITED Tel +385 20 322 166 Antuninska 6 (old town) Fax +385 20 322 167 20000 Dubrovnik [email protected] Croatia www.warphotoltd.com This photographic exhibition has been curated and exhibited by War Photo Limited, it is now available on a rental basis, for further information please contact Wade Goddard CHILD SOLDIER photographs by: Jan Grarup / NOOR Yannis Kontos / Polaris Alixandra Fazzina / Trolley / NOOR Noel Quidu Franco Pagetti / VII forward by Luis Moreno Ocampo There are an estimated 300,000 children in fighting forces around the world, many of whom have been forcibly recruited or abducted; they have suffered beatings and other forms of torture; and psychological damage resulting from being forced to kill others. Girl soldiers have suffered the additional humiliation of rape and sexual servitude, sometimes over periods of several years. © Jan Grarup / NOOR © Yannis Kontos / Polaris © Alixandra Fazzina © Noel Quidu Biographies Biography of Jan Grarup / Noor Denmark, 1968 - Over the last 18 years, Jan has travelled the world documenting many of the defining mo- ments of history. From the fall of the communist regime in Romania to the current occupation of Iraq, he has covered numerous wars and conflicts, including the genocide in Rwanda. Jan has documented daily life on both sides of the intifada with his stories “The boys from Ramallah” and “The boys from Hebron”. In 2006 he published the book Shadowland. Jan is a recipient of numerous awards and resides in Copenhagen. Biography of Yannis Kontos / Polaris Yannis Kontos was born in Ioannina, Greece in 1971, a freelance professional photojournalist; Yannis was first associated with the French international agencies Sygma (1998-2000) and Gamma (2001-2002) and has been affiliated with the American agency Polaris Images from its inception. -

Menstrual Hygiene Around the World

A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world Sarah House, Thérèse Mahon and Sue Cavill p.2 Introductory pages Copyright © WaterAid. All rights reserved. This material is under copyright but may be reproduced by any method for educational purposes by anyone working to improve the lives of women and girls through strengthening menstrual hygiene knowledge and practices, as long as the source is clearly referenced. It should not be reproduced for sale or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the copyright holders. The authors would appreciate receiving information on when, where and for what purpose the materials have been used. Please send details to [email protected] Disclaimer This resource is a synthesis of good practice. While every effort has been made to obtain permission for the inclusion of materials, and also to verify that information is from a reputable source, checks have not been possible for all entries. Therefore, users are encouraged to follow up with the original references when considering using sections of this resource. This resource is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical conditions. WaterAid has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but makes no warranty as to its accuracy. A doctor or other healthcare professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. All examples of commercial products included within this resource are for learning purposes only and do not suggest endorsement by WaterAid and co-publishing organisations. Cover: A young woman producing low cost, First edition, 2012 hygienic sanitary pads in Mirpur, Dhaka. -

Refugee Women's Leadership in Jordan

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan Widad Hassan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2016 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BEYOND VULNERABILITY: REFUGEE WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN JORDAN By WIDAD HASSAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 WIDAD HASSAN All Rights Reserved iii Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan By Widad Hassan The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Thomas G. Weiss Thesis Advisor ____________________ _______________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan By Widad Hassan Advisor: Thomas G. Weiss While both men and women are affected by conflicts and humanitarian crises, 80 percent of the world’s refugees and internally displaced persons are women and children, indicating that women experience conflict and war differently. The emphasis on women’s vulnerability during conflicts and humanitarian crises leads to their exclusion from leadership roles and decision- making on humanitarian programs and issues that impact them. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Gr 2010 Operational Support A

Operational support and management Executive Direction and Management Headquarters (including the DIST Hub in Kuala Lumpur), and an ad hoc inspection of an operation in Africa to look into The formulates policy, ensures effective reported management concerns, were also conducted. management and accountability, and oversees UNHCR activities An Inspection Review Board (IRB), comprising members worldwide. It designates corporate and operational priorities in mandated to provide an objective analysis of each inspection consultation with senior management and endeavours to secure report, was piloted in 2010. At the end of its trial phase, it was political and financial support for the organization. The assessed as having enhanced the quality of inspection reports. Executive Office comprises the High Commissioner, the Deputy One advanced and one basic inspection training workshop High Commissioner, the two Assistant High Commissioners for were held. The advanced workshop was attended by both IGO Operations and for Protection, the Chef de Cabinet, and their and selected non-IGO staff from HQ and field operations. The staff. The Inspector General's Office, the Ethics Office, and basic workshop was attended by senior HQ-based colleagues UNHCR's office in New York report directly to the High with a view to further expanding the Inspection Service’s roster Commissioner and work in close coordination with the Chef de of non-IGO participants who could participate in future Cabinet. inspection missions. The ensures that all staff members A review of lessons learned from 2010 inspections was understand, observe and perform their functions consistent with undertaken, which resulted in an action plan to adjust the the highest standards of integrity and fosters a culture of respect, “Conduct of Inspections” methodology in 2011, including further transparency and accountability throughout the organization. -

High Commissioner's Opening Statement to 61St Session of Excom Palais Des Nations, Geneva 4 October 2010 Check Against Deliver

UNHCR Case postale 2500 Tel.: +41 22 739 8282 CH-1211 Genève 2 Fax: +41 22 739 7314 Email: [email protected] High Commissioner’s Opening Statement to 61st Session of Excom Palais des Nations, Geneva 4 October 2010 Check against delivery Mr. Chairman, Honourable Ministers, Excellencies. May I express my very deep gratitude and appreciation for your leadership and support. Thank you very much on behalf of UNHCR. In December of this year, UNHCR will mark its 60th birthday. Next year we will celebrate that same anniversary for the 1951 Refugee Convention, as well as the 50th anniversary of the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness. We will also mark 150 years since the birth of the first High Commissioner for Refugees at the League of Nations, Fridtjof Nansen. All these anniversaries present an opportunity to broaden and renew support for the principles of international protection upon which our work depends. I am thus delighted to welcome you all to this 61st session of UNHCR’s Executive Committee. Ladies and gentlemen, In this first Excom since being re-elected in April, I would like to begin my remarks by exploring the increasing resilience of conflict and its implications for our work. Last year was the worst in two decades for the voluntary repatriation of refugees. Only approximately 250,000 returned home. And that is about one quarter of the annual average over the past ten years. And there is a simple explanation for this. The changing nature and the growing intractability of conflict make achieving and sustaining peace more difficult in today’s world. -

Bulletin of the World Health Organization

NewsNews Public health round-up More health workers needed Meeting demand for the oral cholera vaccine Some countries in the WHO European Region may not have enough health workers to respond to the growing health needs of their ageing populations in coming years, according to a WHO report. The report, entitled Core health indicators in the WHO European Region 2015, with a special focus on human resources, shows that health workforce shortages and imbalances constitute a major public health concern for the region that requires prompt action. Although the number of health- care workers has increased overall in Pezzoli the region by nearly 10% over the last decade, this growth was uneven between WHO/L countries and not necessarily in the The global oral cholera vaccine supply is set to double to 6 million doses this year after the countries where health professionals are World Health Organization (WHO) approved a third producer of the vaccine, Eubiologics most needed, the report said. Co., Ltd based in the Republic of Korea. Vaccine manufacturers must be approved under One in three physicians is more the WHO’s pre-qualification programme so that United Nations agencies can buy their than 55 years old, an increase of 6 per- vaccines. The photograph shows a 2015 cholera vaccination campaign in Malawi. centage points over the past 7 years. http://www.who.int/cholera/vaccines/double The report found that there were five times more physicians in some countries than in others, and that some countries had nine times fewer nurses Ebola transmission ends in virus after 42 days or two incubation than others calculated per head of popu- Guinea cycles of the Ebola virus since the last lation. -

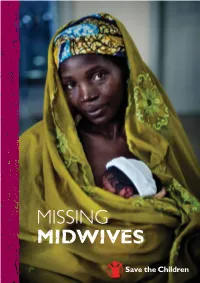

MISSING MIDWIVES MISSING MIDWIVES Save the Children Works in More Than 120 Countries

MISSING MIDWIVES MISSING MIDWIVES Save the Children works in more than 120 countries. We save children’s lives. We fi ght for their rights. We help them fulfi l their potential. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was written by Kathryn Rawe, Advocacy Offi cer, Save the Children UK, with support from Sarah Williams, Health Adviser, Save the Children UK; and from Kate Kerber, Newborn Health Adviser, and Joy Lawn, Director of Global Evidence and Policy, at Save the Children USA/Saving Newborn Lives. Thanks are also due to Nouria Bricki, Lara Brearley, Simon Wright, Patrick Watt and Kitty Arie. Published by Save the Children UK 1 St John’s Lane London EC1M 4AR UK +44 (0)20 7012 6400 savethechildren.org.uk First published 2011 © The Save the Children Fund 2011 The Save the Children Fund is a charity registered in England and Wales (213890) and Scotland (SC039570). Registered Company No. 178159 This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee or prior permission for teaching purposes, but not for resale. For copying in any other circumstances, prior written permission must be obtained from the publisher, and a fee may be payable. Cover photo: Katsina, northern Nigeria. Uleima, holding her baby boy, has been trained by hospital staff in ‘kangaroo mother care’, a technique of providing warmth and comfort to premature babies through skin-to-skin contact, as an alternative to an incubator. (Photo: Pep Bonet/Noor) Typeset by Grasshopper Design Company Printed by Stephen Austin Ltd CONTENTS FOREWORD v SUMMARY vii 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. MIDWIVES SAVE LIVES 7 3. -

MONTHS on Mois Après

AgenceACTED d’Aide à la Coopération Technique et au Développement www.acted.org NEWSLETTER #70 Focus April / Avril 2011 PAKISTAN MONTHS ON 9 MOIS APRÈS MISSION TERRE-OCéan towards new horizons / vers de nouveaux horizons KYRGYZSTAN - Mapping for a better assessment KIRGHIZISTAN - Cartographier pour mieux évaluer DRC - Marching for women / RDC - Marcher pour les femmes Contents / Sommaire ACTED NEWSLETTER #70 April / Avril 2011 6 News from the field / Nouvelles du terrain Mission Terre-Océan, towards new horizons CTED and the French NGO Ecole de l’Aventure have joined forces to set up “Mission Terre- Océan”, an initiative A aimed at conducting scientific, cultural and humanitarian © ACTED 2011 missions with the French sailing boat La Boudeuse throughout the world, with a strong will to keep Man at the heart of worldwide concerns and to promote a humanist and sustainable environment. PAKISTAN FOCUS The goal of Mission Terre-Océan is to resume the exploration campaigns of La Boudeuse and to contribute to global issues such as environmental problems, climate change and humanitarian © ACTED / Alixandra Fazzina / NOOR Images - 2011 challenges. These missions will be dedicated to biodiversity, environment protection and sustainable development. They 22 favor a dialogue between cultures, a necessary component of international cooperation. The next Mission Terre-Océan campaign will focus on the impact of climate change on populations around the world, and ACTED will provide its experience of development projects for climate change victims or vulnerable populations. With La Boudeuse, ACTED wishes to offer a new action model that brings a scientific approach, advocacy campaigns and grassroots interventions together. The idea is to propose an adapted response to the environmental and human challenges of today and tomorrow. -

Research Report

Trends, factors and risks of unaccompanied child migration from Ethiopia through the eastern migration routes Research Report Ethiopian and Somali refugees and migrants waiting for smugglers to take them across the Gulf of Aden to Yemen. Credit: UNHCR/Alixandra Fazzina. Save the Children Ethiopia February 2021 Analysis and writing by Chris Horwood and Katherine Grant. Ravenstone Consult. With field research by Includovate Ethiopia. 1 Contents 1. Executive summary and recommendations Page 4 1.1 Executive summary Page 4 1.2 Recommendations Page 7 2. Introducing the migration context Page 13 2.1 The migratory context 2.2 Institutional and programmatic context 3. Research Framework Page 21 4. Methodology, definitions & limitations Page 23 5. Findings and analysis with key takeaways Page 27 5.1 Flow volume and demographic characteristics Page 27 5.2 Characteristics and trends of irregular migration (east) Page 34 5.2.1 Popularity of the eastern route 5.2.2 Destination choices 5.2.3 Duration intentions 5.2.4 Use of smugglers 5.2.5 Use of technology 5.2.6 Returns of child migrants 5.2.7 Re-migration of child migrants 5.2.8 Resorting to irregularity 5.2.9 Risks and protection factors of the eastern route 5.2.10 Gendered conditions and risks 5.2.11 The impact of Covid-19 5.3 Perceptions of success, failure & migration ‘culture’ Page 50 5.3.1 Migration ‘success’ rates 5.3.2 Impacts of migration ‘failure’ 5.3.3 The impact of success 5.3.4 ‘culture of migration’ and notions of success 5.4 Perception of risk Page 59 5.5 Migration decisions and root causes Page 64 5.6 Financial and social aspirations of migrants Page 70 5.7 Assistance, services, and responses Page 72 5.7.1 Assistance during the migration journey 5.7.2 Parents and children’s perspectives 5.7.3 Government stakeholder perspectives 5.7.4 Existing areas of engagement 5.7.5 Suggested interventions / responses 6. -

Annual Report(2009-2010)

ANNUAL REPORT (2009-2010) with Accounts CHAIR’S REPORT THE PAST YEAR HAS SEEN CRISIS ActION COME OF AGE. WITH OFFICES IN SEVEN COUNTRIES, ON THREE CONTINENTS, IT HAS WELL AND TRULY EStaBLISHED ITSELF AS AN INTERNatIONALLY RECOGNISED AND RESPEctED actOR ON THE CONFLIct PREVENTION StaGE. The scope of its work is impressive – from bringing together civil society across 19 countries to campaign on Sudan, to mobilising an unprecedented network of European organisations on Gaza. Through the efforts of its Cairo office, it is now a trusted and valued partner for Arab civil society and has managed to scale up its activities tremendously in the Middle East and North Africa region. It will soon be doing similar work with African partners through its newly established Nairobi office. Given the rapid expansion of Crisis Action over the last three years, the focus will now be on consolidation, and ensuring that the larger organisation doesn’t lose its nimbleness and responsiveness. The financial position is good, and sustainable: income passed the €1 million mark for the first time this year, and the Board is confident that the organisation can continue to raise this amount on an ongoing basis with the support of its core partners and donors. The impact Crisis Action achieves with its limited means continues to impress. Despite its geographical spread, the organisation has just 14 staff. This is worth bearing in mind as one reads through the extensive list of achievements and results in this year’s annual report. Crisis Action’s Board is also undergoing its own changes. -

A Million SHILLINGS

a million SHILLINGS Nineteen-year-old Salima sits nervously in a dark, cramped room of a smuggler's house in the photographs & text by Alixandra Fazzina slums of Basatine, Yemen. Having fled her home in Mogadishu following the death of her husband and baby son in a editor+designer: Yumi Goto mortar attack, at seven months pregnant Salima translator: Saya Namikawa made the decision to flee to Yemen for her own safety. Caught up in a chain controlled by human text editor: Karen Coates, Akiko Higgins traffickers, she spent 20 days in trucks before reaching Somalia's northern coast from where design production assistant: Kishin Shimomoto she would make the perilous journey across the Gulf of Aden. Packed into a tiny fishing boat with 120 other migrants, Salima went into labour during the two-day crossing. Having passed out, she only remembers waking up to see the smugglers throw her newborn baby overboard into the sea. Finding her way to Aden, the traumatised teenager once again found herself with smuggling gangs who send women to Saudi Arabia. Without any money, this is the only place she can stay in safety. バサティーンのスラム街にある密入国斡旋業者の家。 暗く窮屈な部屋で、不安にかられる19歳のサリマ。 砲撃で夫と赤ん坊だった息子を亡くしたとき妊娠 7ヶ月だった彼 女は、自分の身を守るためにモガ ディシュの家を出てイエメンへ逃げようと決意した。 アデン湾を渡る船が出港するソマリア北部の海岸 に着くまで、斡旋業者によって鎖で縛られたまま20 日間をトラックの中で過ごした。120人もの亡命者 と共に小さな漁船にぎゅうぎゅうに押し込まれた サリマは、2日間の航海中に陣痛を迎えてしまった。 気絶した彼女が次に目を覚ましたとき、生まれて きた赤ん坊は斡旋業者たちによって海に投げ捨て られるところだった。 アデンへたどり着いたものの、トラウマを抱えた 彼女は再び斡旋業者のもとにいた。彼らは女性を サウジアラビアへ引き渡そうとしていたが、お金が ない彼女にとって、ここが 唯 一 安 全 に生きながらえる ことのできる場 所 だ 。 A group of Somali migrants anxiously look back from the sea for friends and relatives left behind on the beach as they prepare to board a smuggler's boat moored off the coast at Shimbelle.