State of World Population 2017 Population World of State State of World Population 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

Seals, Amulets and Coinages of Dvāravatī Cultural Sites: Understanding Their Social Environment and Religious Network

SEALS, AMULETS AND COINAGES OF DVĀRAVATĪ CULTURAL SITES: UNDERSTANDING THEIR SOCIAL ENVIRONMENT AND RELIGIOUS NETWORK Suchandra Ghosh and Lipi Ghosh University of Calcutta, India; [email protected] (for both) ABSTRACT religious cultural milieu of a society. These include the votive This paper focuses on minor artifacts, such as sealings, sealings, tablets, coins, small figurines and amulets recovered tablets, coinages, small figurines and amulets, that form from various sites in Thailand that are attributed to the integral parts of the socio-religious cultural milieu of a Dvāravatī cultural period. Just as the writing systems, society. Such objects were recovered from various sites in honorific titles and art styles indicate extensive contact with Thailand attributed to the Dvāravatī cultural period, and India, this paper will try to understand the nature of linkage they lead us to two concerns: First, what the nature of the with the Indian subcontinent through these minor objects. society was that encouraged production and use of objects The fact that the commencement of Dvāravatī Culture should like sealings, terracotta figurines and amulets, and second, be pushed back at least 200 years before the generally the persons that made them and the agency that percolated accepted date of around CE 600 (Glover and Barram 2008) such socio-religious beliefs/rituals in the mind of people. An is in accordance with the nature of these objects. overview of archaeological materials recovered from A study of these objects leads us to certain questions: Dvāravatī sites in central Thailand allow us to perceive a What was the nature of the society that encouraged kind of society where Buddhism dominated, with elements of production and use of objects like these sealings, terracotta Brahmanism in its rituals. -

AFE-ADB News No 47.Indd

No. 47| September 2015 The Newsletter of the Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank Baku Annual General Meeting People, Places, and Passages Chapter News IN THIS ISSUE Our Cover No. 47| September 2015 The Newsletter of the SEPTEMBER 2015 Association of Former Employees of the Asian Development Bank Baku 3 AFE–ADB Updates Annual General Meeting 3 From the AFE President 3 From the AFE Vice President People, Places, 3 Pension Matters and Passages 4 Health Matters 6 AFE–ADB Committees 6 Chapter Coordinators Chapter News 6 Frankfurt 2016 7 Azerbaijan 2015 7 Chapter Coordinators’ Meeting Top left: Heydar Aliyev Center in Azerbaijan; 9 AFE–ADB 28th Annual General Meeting middle right: Prabhu Ghate; below: Japan 13 Participants Chapter; background: Suzani. 14 Cocktails 17 Baku and Surrounds 19 Chapter News AFE–ADB News Publisher: Hans-Juergen Springer 19 Japan 20 Philippines: South Group’s Special Taal Experience Publications Committee: Jill Gale de Villa 22 East Group Brings Cheer to Inmates (head), Gam de Armas, Stephen Banta, Wickie Mercado, David Parker, Hans-Juergen Springer. 23 People, Places, and Passages Graphic Assistance: Josephine Jacinto-Aquino 27 Amazing Caucasus 30 Like Flowers in the Sand Photographs: ADB Photo Bank and archives, 34 Horas, Aloha, Bula ADB’s Security Detachment, Nihal 35 Nihal Amerasinghe’s Latest Launch Amerasinghe,Stephen Banta, Peter Carroll, 36 News from Pakistan Peter Darjes, Gam de Armas, Jill Gale de Villa, 36 Looming Challenges with Elderly Care: ADB and Asia Gordon Fox, Prabhu Ghate, Ariel Javellana, 37 Updates on UP’s Strategic Initiatives Abdul Gafar Nasution, Susana Padolina, David 38 Miriam vs. -

The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries Pierre-Yves Manguin

The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries Pierre-Yves Manguin To cite this version: Pierre-Yves Manguin. The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries. Moussons : recherches en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est, Presses universitaires de Provence, 2014, Recherche en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est, pp.73- 99. 10.4000/moussons.2699. halshs-02516998 HAL Id: halshs-02516998 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02516998 Submitted on 24 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Moussons Recherche en sciences humaines sur l’Asie du Sud-Est 5 | 2002 Recherche en sciences humaines sur l'Asie du Sud-Est The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries La nature informe des systèmes politiques de l’Asie du sud-est insulaire : centres restreints, périphéries étendues Pierre-Yves Manguin Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/moussons/2699 DOI: 10.4000/moussons.2699 ISSN: 2262-8363 Publisher Presses Universitaires de Provence Printed version Date of publication: 1 July 2002 Number of pages: 73-99 ISBN: 2-7449-0415-5 ISSN: 1620-3224 Electronic reference Pierre-Yves Manguin, « The Amorphous Nature of Coastal Polities in Insular Southeast Asia: Restricted Centres, Extended Peripheries », Moussons [Online], 5 | 2002, Online since 19 June 2014, connection on 20 April 2019. -

Investing in Maternal, Newborn and Child Health

INVESTING IN MATERNAL, NEWBORN AND CHILD HEALTH THE CASE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC Investing in Maternal, Newborn and Child Key messages Health - The Case for Asia and the Pacific Halfway to the MDG target date, it is clear that the “business as usual” approach to Every year 9.2 million children in the world die before their fifth birthday, as do the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4 and 5 - to reduce child and maternal more than half a million pregnant women.1 The situation is particularly acute in mortality and achieve universal access to reproductive health - is failing too many Asia and the Pacific, whose share of the global total is nearly 41% of the under- 2-3 people in too many places in Asia and the Pacific. The lives of women and children fives, more than 44% of the mothers and 56% of the newborn babies. Most of are demonstrably affected by the quantity and quality of spending on maternal, these deaths could be prevented through proven, cost-effective interventions. Furthermore, of all the people in the world who require family planning services, newborn and child health – and governments have the power to fix the problem. but do not have access to them, 55% live in Asia and the Pacific.4 This investment case shows the cost and impact of increased investment in proven and cost-effective reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health interventions. The scale of this tragedy means that the global Millennium Development Goals It is an investment in social justice, social stability and economic productivity. -

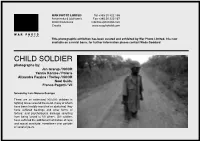

Child Soldier

WAR PHOTO LIMITED Tel +385 20 322 166 Antuninska 6 (old town) Fax +385 20 322 167 20000 Dubrovnik [email protected] Croatia www.warphotoltd.com This photographic exhibition has been curated and exhibited by War Photo Limited, it is now available on a rental basis, for further information please contact Wade Goddard CHILD SOLDIER photographs by: Jan Grarup / NOOR Yannis Kontos / Polaris Alixandra Fazzina / Trolley / NOOR Noel Quidu Franco Pagetti / VII forward by Luis Moreno Ocampo There are an estimated 300,000 children in fighting forces around the world, many of whom have been forcibly recruited or abducted; they have suffered beatings and other forms of torture; and psychological damage resulting from being forced to kill others. Girl soldiers have suffered the additional humiliation of rape and sexual servitude, sometimes over periods of several years. © Jan Grarup / NOOR © Yannis Kontos / Polaris © Alixandra Fazzina © Noel Quidu Biographies Biography of Jan Grarup / Noor Denmark, 1968 - Over the last 18 years, Jan has travelled the world documenting many of the defining mo- ments of history. From the fall of the communist regime in Romania to the current occupation of Iraq, he has covered numerous wars and conflicts, including the genocide in Rwanda. Jan has documented daily life on both sides of the intifada with his stories “The boys from Ramallah” and “The boys from Hebron”. In 2006 he published the book Shadowland. Jan is a recipient of numerous awards and resides in Copenhagen. Biography of Yannis Kontos / Polaris Yannis Kontos was born in Ioannina, Greece in 1971, a freelance professional photojournalist; Yannis was first associated with the French international agencies Sygma (1998-2000) and Gamma (2001-2002) and has been affiliated with the American agency Polaris Images from its inception. -

Constituting Religion

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 154.5.53.196, on 09 Aug 2018 at 22:42:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/888E17F4ACC3739CE1AA443FD07C9BA8 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 154.5.53.196, on 09 Aug 2018 at 22:42:15, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/888E17F4ACC3739CE1AA443FD07C9BA8 constituting religion Most Muslim-majority countries have legal systems that enshrine both Islam and liberal rights. While not necessarily at odds, these dual commitments nonetheless provide legal and symbolic resources for activists to advance contending visions for their states and societies. Using the case study of Malaysia, Constituting Religion examines how these legal arrangements enable litigation and feed the construction of a “rights-versus-rites binary” in law, politics, and the popular imagination. By drawing on extensive primary source material and tracing controversial cases from the court of law to the court of public opinion, this study theorizes the “judicialization of religion” and examines the radiating effects of courts on popular legal and religious consciousness. The book docu- ments how legal institutions catalyze ideological struggles that stand to redefine the nation and its politics. Probing the links between legal pluralism, social movements, secularism, and political Islamism, Constituting Religion sheds new light on the con- fluence of law, religion, politics, and society. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at https://doi.org/10.1017/ 9781108539296. -

Menstrual Hygiene Around the World

A resource for improving menstrual hygiene around the world Sarah House, Thérèse Mahon and Sue Cavill p.2 Introductory pages Copyright © WaterAid. All rights reserved. This material is under copyright but may be reproduced by any method for educational purposes by anyone working to improve the lives of women and girls through strengthening menstrual hygiene knowledge and practices, as long as the source is clearly referenced. It should not be reproduced for sale or commercial purposes without prior written permission from the copyright holders. The authors would appreciate receiving information on when, where and for what purpose the materials have been used. Please send details to [email protected] Disclaimer This resource is a synthesis of good practice. While every effort has been made to obtain permission for the inclusion of materials, and also to verify that information is from a reputable source, checks have not been possible for all entries. Therefore, users are encouraged to follow up with the original references when considering using sections of this resource. This resource is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical conditions. WaterAid has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but makes no warranty as to its accuracy. A doctor or other healthcare professional should be consulted for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions. All examples of commercial products included within this resource are for learning purposes only and do not suggest endorsement by WaterAid and co-publishing organisations. Cover: A young woman producing low cost, First edition, 2012 hygienic sanitary pads in Mirpur, Dhaka. -

Refugee Women's Leadership in Jordan

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan Widad Hassan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2016 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BEYOND VULNERABILITY: REFUGEE WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN JORDAN By WIDAD HASSAN A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2017 ii © 2017 WIDAD HASSAN All Rights Reserved iii Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan By Widad Hassan The manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________ ______________________________________ Date Thomas G. Weiss Thesis Advisor ____________________ _______________________________________ Date Elizabeth Macaulay-Lewis Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Beyond Vulnerability: Refugee Women’s Leadership in Jordan By Widad Hassan Advisor: Thomas G. Weiss While both men and women are affected by conflicts and humanitarian crises, 80 percent of the world’s refugees and internally displaced persons are women and children, indicating that women experience conflict and war differently. The emphasis on women’s vulnerability during conflicts and humanitarian crises leads to their exclusion from leadership roles and decision- making on humanitarian programs and issues that impact them. -

Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F

8 88 8 88 Organizations 8888on.com 8888 Basic Photography in 180 Days Book XVIII Prizes and Organizations Editor: Ramon F. aeroramon.com Contents 1 Day 1 1 1.1 Group f/64 ............................................... 1 1.1.1 Background .......................................... 2 1.1.2 Formation and participants .................................. 2 1.1.3 Name and purpose ...................................... 4 1.1.4 Manifesto ........................................... 4 1.1.5 Aesthetics ........................................... 5 1.1.6 History ............................................ 5 1.1.7 Notes ............................................. 5 1.1.8 Sources ............................................ 6 1.2 Magnum Photos ............................................ 6 1.2.1 Founding of agency ...................................... 6 1.2.2 Elections of new members .................................. 6 1.2.3 Photographic collection .................................... 8 1.2.4 Graduate Photographers Award ................................ 8 1.2.5 Member list .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Books ............................................. 8 1.2.7 See also ............................................ 9 1.2.8 References .......................................... 9 1.2.9 External links ......................................... 12 1.3 International Center of Photography ................................. 12 1.3.1 History ............................................ 12 1.3.2 School at ICP ........................................ -

Gr 2010 Operational Support A

Operational support and management Executive Direction and Management Headquarters (including the DIST Hub in Kuala Lumpur), and an ad hoc inspection of an operation in Africa to look into The formulates policy, ensures effective reported management concerns, were also conducted. management and accountability, and oversees UNHCR activities An Inspection Review Board (IRB), comprising members worldwide. It designates corporate and operational priorities in mandated to provide an objective analysis of each inspection consultation with senior management and endeavours to secure report, was piloted in 2010. At the end of its trial phase, it was political and financial support for the organization. The assessed as having enhanced the quality of inspection reports. Executive Office comprises the High Commissioner, the Deputy One advanced and one basic inspection training workshop High Commissioner, the two Assistant High Commissioners for were held. The advanced workshop was attended by both IGO Operations and for Protection, the Chef de Cabinet, and their and selected non-IGO staff from HQ and field operations. The staff. The Inspector General's Office, the Ethics Office, and basic workshop was attended by senior HQ-based colleagues UNHCR's office in New York report directly to the High with a view to further expanding the Inspection Service’s roster Commissioner and work in close coordination with the Chef de of non-IGO participants who could participate in future Cabinet. inspection missions. The ensures that all staff members A review of lessons learned from 2010 inspections was understand, observe and perform their functions consistent with undertaken, which resulted in an action plan to adjust the the highest standards of integrity and fosters a culture of respect, “Conduct of Inspections” methodology in 2011, including further transparency and accountability throughout the organization. -

Countdown to 2015 Decade Report (2000–2010) Taking Stock of Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival

Countdown to 2015 deCade report (2000–2010) Taking stock of maternal, newborn and child survival TAKING STOCK OF MATERNAL, NEWBORN AND CHILD SURVIVAL 2000–2010 DECADE REPORT i Contributors Production editor: Jennifer Requejo (PMNCH/Johns Technical working groups Hopkins University) Coverage: Jennifer Bryce (co-chair), Tessa Wardlaw Lead writers: Jennifer Requejo (PMNCH/Johns Hopkins (co-chair), Holly Newby, Archana Dwivedi, Jennifer Requejo, University), Jennifer Bryce (Johns Hopkins University) Alison Moran, Shams El Arifeen, Edilberto Loiaza, Angella Mtimumi, Blerta Maliqi, Lale Say, James Tibenderana, Anuli Subeditors/writers: Joy Lawn (Save the Children/Saving Ajene Newborn Lives), Peter Berman (World Bank), Bernadette Daelmans (WHO), Laura Laski (UNFPA), Cesar Victora Equity: Cesar Victora (co-chair), Ties Boerma (co-chair), (Universidade de Pelotas), Elizabeth Mason (WHO) Aluisio Barros, Carine Ronsmans, Wendy Graham, Edilberto Loiaza, Betty Kirkwood, Zulfiqar Bhutta, Kate Kerber, Henrik Profile support team: Tessa Wardlaw (UNICEF), Holly Axelson Newby (UNICEF), Archana Dwivedi (UNICEF) Financing: Peter Berman (chair), Henrik Axelson, Giulia Additional writing team: Henrik Axelson (PMNCH), Greco, Ruth Levine, David Collins, Giorgio Cometto, Zulfiqar Bhutta (Aga Khan University), Ties Boerma (WHO), Jacqueline Mahon, Ravi Rannan-Eliya, Josh Lozman, Nouria Flavia Bustreo (PMNCH), Eleanora Cavagnero (WHO), Brikci, Karin Stenberg, Dan Kraushaar Mickey Chopra (UNICEF), Giorgio Cometto (Global Health Workforce Alliance), Andres de Francisco