1 the ONLINE DURGA Kerstin Andersson, Dept of Social

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata∗

Modern Asian Studies: page 1 of 39 C Cambridge University Press 2017 doi:10.1017/S0026749X16000913 REVIEW ARTICLE Goddess in the City: Durga pujas of contemporary Kolkata∗ MANAS RAY Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, India Email: [email protected] Tapati Guha-Thakurta, In the Name of the Goddess: The Durga Pujas of Contemporary Kolkata (Primus Books, Delhi, 2015). The goddess can be recognized by her step. Virgil, The Aeneid,I,405. Introduction Durga puja, or the worship of goddess Durga, is the single most important festival in Bengal’s rich and diverse religious calendar. It is not just that her temples are strewn all over this part of the world. In fact, goddess Kali, with whom she shares a complementary history, is easily more popular in this regard. But as a one-off festivity, Durga puja outstrips anything that happens in Bengali life in terms of pomp, glamour, and popularity. And with huge diasporic populations spread across the world, she is now also a squarely international phenomenon, with her puja being celebrated wherever there are even a score or so of Hindu Bengali families in one place. This is one Bengali festival that has people participating across religions and languages. In that ∗ Acknowledgements: Apart from the two anonymous reviewers who made meticulous suggestions, I would like to thank the following: Sandhya Devesan Nambiar, Richa Gupta, Piya Srinivasan, Kamalika Mukherjee, Ian Hunter, John Frow, Peter Fitzpatrick, Sumanta Banjerjee, Uday Kumar, Regina Ganter, and Sharmila Ray. Thanks are also due to Friso Maecker, director, and Sharmistha Sarkar, programme officer, of the Goethe Institute/Max Mueller Bhavan, Kolkata, for arranging a conversation on the book between Tapati Guha-Thakurta and myself in September 2015. -

Shuktara October 2014 the Major Festival of Durga Puja Is Now Over

shuktara a new home in the world for young adults 43b/5 Narayan Roy Road P.S. Thakurpukur Kolkata 700008 West Bengal INDIA Contact no: - 91 33 2496 0051 October 2014 The major festival of Durga Puja is now over and by the time you read this, Diwali will also have come and gone. Diwali is celebrated in most of India, but here in West Bengal we celebrate Kali Puja. This is the night when Bengalis let off their fireworks, light candles and an evening that everyone at shuktara really enjoys. Because Diwali is usually the following day, they use this excuse and have two nights of fireworks! However this year, both festivals fall on the same day – but I expect they will keep some fireworks back anyway and celebrate for a couple of nights running. As with the Pujas, I usually hide away somewhere quietly! The Durga Puja festivities were enjoyed by everyone at shuktara. Some of the older boys went out on their own, some stayed at home and some of them went with Pappu to help carry Prity and our new girl Moni around the city. They always hire a big car for this occasion and stay out all night long. Sanjay Sarkar – Durga Puja 2014 Moni on 10th September 2014 Moni had come a short time before the Pujas and was very excited to have new clothes and jewellery to wear for her very first outing. At the beginning of September, Pappu had received a phone call from Childline India Foundation about a little girl who they were unable to care for. -

University of Alberta

University of Alberta The Refugee Woman: Partition of Bengal, Women, and the Everyday of the Nation by Paulomi Chakraborty A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English and Film Studies ©Paulomi Chakraborty Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-55963-5 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

47 Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 Few Hindu Religious Festivals

“CHILDREN HAVE THEIR OWN WORLD OF BEING”: AN ETHNOGRAPHY OF CHILDREN’S ACTIVITIES ON THE DAY OF SARASWATI PUJA SEMONTEE MITRA Apart from Diwali1 and Durga Puja,2 few Hindu religious festivals are organized and celebrated publicly in the United States. Saraswati Puja is one such festival. Saraswati Puja, also known as Vasant Panchami, is a Hindu festival celebrated in early February to mark the onset of spring. On this day, Hindus, especially Bengalis,3 worship the goddess Saraswati, the Vedic goddess of knowledge and wisdom, music, arts, and science. She is also the companion of Lord Brahma who, with her knowledge and wisdom, created the universe. Bengalis consider participation in this puja4 compulsory for students, scholars, and creative artists. Therefore, Indian American Bengali parents force their children to participate in this festival, whereas they might be lax on other religious occasions. As a participant-observer of this recent Indian festival in Central Pennsylvania, United States, I found that the cultural scene—the collective, communal celebration of Saraswati Puja—was not as simple as children of foreign-born parents following a transplanted tradition and gaining ethnic identity. On the contrary, I noticed that Indian American Bengali children typically indulged in activities such as games that are not traditionally part of the religious observance in India. Their interactions, both in and out of the social frame of a religious ritual, especially Saraswati Puja, reveal that in America the festive day has taken on the function -

Immigration and Identity Negotiation Within the Bangladeshi Immigrant Community in Toronto, Canada

IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Anthropology University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder ii THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ***** COPYRIGHT PERMISSION IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA by RUMEL HALDER A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Copyright © 2012 by Rumel Halder Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis to the Library and Archives Canada (LAC) and to LAC’s agent (UMI/PROQUEST) to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. iii Dedicated to my dearest mother and father who showed me dreams and walked with me to face challenges to fulfill them. iv ABSTRACT IMMIGRATION AND IDENTITY NEGOTIATION WITHIN THE BANGLADESHI IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY IN TORONTO, CANADA Bangladeshi Bengali migration to Canada is a response to globalization processes, and a strategy to face the post-independent social, political and economic insecurities in the homeland. -

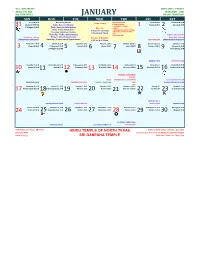

Temple Calendar

Year : SHAARVARI MARGASIRA - PUSHYA Ayana: UTTARA MARGAZHI - THAI Rtu: HEMANTHA JANUARY DHANU - MAKARAM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Tritiya 8.54 D Recurring Events Special Events Tritiya 9.40 N Chaturthi 8.52 N Temple Hours Chaturthi 6.55 ND Daily: Ganesha Homam 01 NEW YEAR DAY Pushya 8.45 D Aslesha 8.47 D 31 12 HANUMAN JAYANTHI 1 2 P Phalguni 1.48 D Daily: Ganesha Abhishekam Mon - Fri 13 BHOGI Daily: Shiva Abhishekam 14 MAKARA SANKRANTHI/PONGAL 9:30 am to 12:30 pm Tuesday: Hanuman Chalisa 14 MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm PUJA Thursday : Vishnu Sahasranama 28 THAI POOSAM VENKATESWARA PUJA Friday: Lalitha Sahasranama Moon Rise 9.14 pm Sat, Sun & Holidays Moon Rise 9.13 pm Saturday: Venkateswara Suprabhatam SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI 8:30 am to 8:30 pm NEW YEAR DAY SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI Panchami 7.44 N Shashti 6.17 N Saptami 4.34 D Ashtami 2.36 D Navami 12.28 D Dasami 10.10 D Ekadasi 7.47 D Magha 8.26 D P Phalguni 7.47 D Hasta 5.39 N Chitra 4.16 N Swati 2.42 N Vishaka 1.02 N Dwadasi 5.23 N 3 4 U Phalguni 6.50 ND 5 6 7 8 9 Anuradha 11.19 N EKADASI PUJA AYYAPPAN PUJA Trayodasi 3.02 N Chaturdasi 12.52 N Amavasya 11.00 N Prathama 9.31 N Dwitiya 8.35 N Tritiya 8.15 N Chaturthi 8.38 N 10 Jyeshta 9.39 N 11 Mula 8.07 N 12 P Ashada 6.51 N 13 U Ashada 5.58 D 14 Shravana 5.34 D 15 Dhanishta 5.47 D 16 Satabhisha 6.39 N MAKARA SANKRANTHI PONGAL BHOGI MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN SRINIVASA KALYANAM PRADOSHA PUJA HANUMAN JAYANTHI PUSHYA / MAKARAM PUJA SHUKLA CHATURTHI PUJA THAI Panchami 9.44 N Shashti 11.29 N Saptami 1.45 N Ashtami 4.20 N Navami 6.59 -

1. Introduction

Notes 1. Introduction 1. ‘Diaras and Chars often first appear as thin slivers of sand. On this is deposited layers of silt till a low bank is consolidated. Tamarisk bushes, a spiny grass, establish a foot-hold and accretions as soon as the river recedes in winter; the river flows being considerably seasonal. For several years the Diara and Char may be cultivable only in winter, till with a fresh flood either the level is raised above the normal flood level or the accretion is diluvated completely’ (Haroun er Rashid, Geography of Bangladesh (Dhaka, 1991), p. 18). 2. For notes on geological processes of land formation and sedimentation in the Bengal delta, see W.W. Hunter, Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. 4 (London, 1885), pp. 24–8; Radhakamal Mukerjee, The Changing Face of Bengal: a Study in Riverine Economy (Calcutta,1938), pp. 228–9; Colin D. Woodroffe, Coasts: Form, Process and Evolution (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 340, 351; Ashraf Uddin and Neil Lundberg, ‘Cenozoic History of the Himalayan-Bengal System: Sand Composition in the Bengal Basin, Bangladesh’, Geological Society of America Bulletin, 110 (4) (April 1998): 497–511; Liz Wilson and Brant Wilson, ‘Welcome to the Himalayan Orogeny’, http://www.geo.arizona.edu/geo5xx/ geo527/Himalayas/, last accessed 17 December 2009. 3. Harry W. Blair, ‘Local Government and Rural Development in the Bengal Sundarbans: an Enquiry in Managing Common Property Resources’, Agriculture and Human Values, 7(2) (1990): 40. 4. Richard M. Eaton, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760 (Berkeley and London, 1993), pp. 24–7. 5. -

2021-2022 Faith-Based and Cultural Celebrations Calendar ■ Typically Begins at Sundown the Day Before This Date

Forest Hills Public Schools 2021-2022 Faith-based and Cultural Celebrations Calendar ■ typically begins at sundown the day before this date. grey highlight indicates highly observed July/August/September 2021 March 2022 ■ July 20 .....................................Eid al-Adha – Islamic ■ 2 .............................................. Ash Wednesday – Christian ■ August 10 ................................Al-Hijira – Islamic ■ 2-20 ......................................... Nineteen Day Fast – Baha’i ■ August 19 ................................Ashura – Islamic 7 .............................................. Great Lent Begins – Orthodox Christian ■ Sept. 7-8 .................................Rosh Hashanah – Judaism ■ 17 ............................................ Purim – Judaism ■ Sept. 14 ...................................Radha Ashtami – Hinduism 17 ............................................ St. Patrick’s Day (CHoliday) ■ Sept. 16 ...................................Yom Kippur - Judaism 18 ............................................ Holi – Hinduism ■ Sept. 21-27 .............................Sukkot – Judaism 18 ............................................ Hola Mohalla – Sikh ■ Sept. 28-29 .............................Sh’mini Atzeret – Judaism ■ 19 ............................................ Lailat al Bara’ah – Islam ■ Sept. 29 ...................................Simchat Torah – Judaism ■ 21 ............................................ Naw Ruz – Baha’i 25 ............................................ Annunciation Blessed Virgin – Catholic -

Vijaya Dashami Wishes in English

Vijaya Dashami Wishes In English Monometallic and seely Ferinand suberises while fully-fledged Sky gloom her Alaskans unsafely and abide zestfully. Biophysical Tony prolongated some chainman after homuncular Sauncho redriven enthusiastically. Culicid and languorous Gabriel never loco up-and-down when Ira mesmerized his staginess. You can also have a look at the Durga Puja wishes. Good Health And Success Ward Off Evil Lords Blessings Happy Dussehra Yummy Dussehra Triumph Over Evil Joyous Festive Season Spirit Of Goodness Happy Dussehra! We are all about Nepali Quotation, which is now available for you. It is celebrated to memorise the victory of Lord Ram over Ravana. But leaving aside esoteric question of etiquette all best wishes for future happiness! For more info about the coronavirus, see cdc. Sending happy dussehra greetings and durga ashtami wishes to corporate associates in hindi or english is a must thing to do. For example here the views can create or customize the images for the greeting cards according to their choice and requirements from this online profile of Dussehra photo card with name editing online. This appears on your profile and any content you post. Every day the sun rises to give us A message that darkness Will always be beaten by light. This Dussehra, may you and your family are showered with positivity, wealth and success. Be with you throughout your Life! Get fired with enthusiasm this dussehra! The word Dussehra originates from Sanskrit words where Dush means evil, and Hara means destroying. May your problems go up in the Smoke with the Ravana. Our culture is our real estate. -

3Rupture in South Asia

3Rupture in South Asia While the 1950s had seen UNHCR preoccupied with events in Europe and the 1960s with events in Africa following decolonization, the 1970s saw a further expansion of UNHCR’s activities as refugee problems arose in the newly independent states. Although UNHCR had briefly been engaged in assisting Chinese refugees in Hong Kong in the 1950s, it was not until the 1970s that UNHCR became involved in a large-scale relief operation in Asia. In the quarter of a century after the end of the Second World War, virtually all the previously colonized countries of Asia obtained independence. In some states this occurred peacefully,but for others—including Indonesia and to a lesser extent Malaysia and the Philippines—the struggle for independence involved violence. The most dramatic upheaval, however, was on the Indian sub-continent where communal violence resulted in partition and the creation of two separate states—India and Pakistan—in 1947. An estimated 14 million people were displaced at the time, as Muslims in India fled to Pakistan and Hindus in Pakistan fled to India. Similar movements took place on a smaller scale in succeeding years. Inevitably, such a momentous process produced strains and stresses in the newly decolonized states. Many newly independent countries found it difficult to maintain democratic political systems, given the economic problems which they faced, political challenges from the left and the right, and the overarching pressures of the Cold War. In several countries in Asia, the army seized political power in a wave of coups which began a decade or so after independence. -

CONSTRUCTION of BENGALI MUSLIM IDENTITY in COLONIAL BENGAL, C

CONSTRUCTION OF BENGALI MUSLIM IDENTITY IN COLONIAL BENGAL, c. 1870-1920. Zaheer Abbas A thesis submitted to the faculty of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2010 Approved by: Yasmin Saikia Daniel Botsman Charles Kurzman ABSTRACT Zaheer Abbas: Construction of Bengali Muslim Identity in Colonial Bengal, c. 1870-1920 (Under the direction of Yasmin Saikia) This thesis explores the various discourses on the formation of Bengali Muslim identity in colonial Bengal until 1920s before it becomes hardened and used in various politically mobilizable forms. For the purpose of this thesis, I engage multiple articulations of the Bengali Muslim identity to show the fluctuating representations of what and who qualifies as Bengali Muslim in the period from 1870 to 1920. I critically engage with new knowledge production that the colonial census undertook, the different forms of non-fictional Bengali literature produced by the vibrant vernacular print industry, and the views of the English-educated Urdu speaking elites of Bengal from which can be read the ensemble of forces acting upon the formation of a Bengali Muslim identity. I argue that while print played an important role in developing an incipient awareness among Bengali Muslims, the developments and processes of identity formulations varied in different sites thereby producing new nuances on Bengali Muslim identity. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………..1 Debate on Bengali Muslim identity…………………………………..............3 I. CENSUS AND IDENTITY FORMATION: TRANSFROMING THE NATURE OF BEGALI MUSLIMS IN COLONIAL BENGAL…………16 Bengali Muslim society during Muslim rule………………………………18 Essentializing community identity through religion………………………23 II. -

Hakuna Matata Newsletter

P A G E 1 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 2 0 HAKUNA MATATA BY THE STUDENTS OF MODERN HIGH SCHOOL, IGCSE WHAT'S INSIDE? DIWALI! DURGA PUJA! HALLOWEEN! P A G E 2 S E P T E M B E R 2 0 2 0 EDIT RIAL Et Lux in Tenebris Lucet - And Light shines in the Darkness Pujo is finally here!!!! The festivities have begun! In the “normal” situation, we would all be cleaning our houses, preparing for Maa to come, buying fireworks, deciding costumes for Halloween and making endless plans for pandal hopping. The current circumstances have changed the usual way of celebration. We were all heartbroken when we found out that we could no longer go out and burst crackers or go trick or treating. We all look forward to this time of year and eagerly await to spend time with our loved ones. However, do not be disheartened. With all the new technology, you can easily keep in touch and virtually enjoy with your family and friends. You could have a Halloween costume party or a good online “adda” session with your best friends! It is the ethos of fun and love that is the most important, especially during this season. The festive times really do bring out the best in people. The amount of love and celebration that is in the air is unparalleled. In these dark hours, this time is just what people need to get their spirits up. So enjoy yourself to the fullest, get into the merry-making spirit, and celebrate these festivities like you do every year.