Still Alive, Dammit!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Morpheus Staff

2012 Morpheus Staff Editor-in-Chief Laura Van Valkenburgh Contest Director Lexie Pinkelman Layout & Design Director Brittany Cook Marketing Director Brittany Cook Cover Design Lemming Productions Merry the Wonder Cat appears courtesy of Sandy’s House-o-Cats. No animals were injured in the creation of this publication. Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 2 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 3 Table of Contents Morpheus Literary Competition Author Biographies...................5 3rd Place Winners.....................10 2nd Place Winners....................26 1st place Winners.....................43 Senior Writing Projects Author Biographies...................68 Brittany Cook...........................70 Lexie Pinkelman.......................109 Laura Van Valkenburgh...........140 Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 4 Author Biographies Logan Burd Logan Burd is a junior English major from Tiffin, Ohio just trying to take advantage of any writing opportunity Heidelberg will allow. For “Onan on Hearing of his Broth- er’s Smiting,” Logan would like to thank Dr. Bill Reyer for helping in the revision process and Onan for making such a fas- cinating biblical tale. Erin Crenshaw Erin Crenshaw is a senior at Heidelberg. She is an English literature major. She writes. She dances. She prances. She leaps. She weeps. She sighs. She someday dies. Enjoy the Morpheus! Heidelberg University Morpheus Literary Magazine 2012 5 April Davidson April Davidson is a senior German major and English Writing minor from Cincin- nati, Ohio. She is the president of both the German Club and Brown/France Hall Council. She is also a member of Berg Events Council. After April graduates, she will be entering into a Masters program for German Studies. -

¬タᆰmichael Jackson Mtv Awards 1995 Full

Rafael Ahmed Shared on Google+ · 1 year ago 1080p HD Remastered. Best version on YouTube Reply · 415 Hide replies ramy ninio 1 year ago Il est vraiment très fort Michael Jackson !!! Reply · Angelo Oducado 1 year ago When you make videos like this I recommend you leave the aspect ratio to 4:3 or maybe add effects to the black bars Reply · Yehya Jackson 11 months ago Hello My Friend. Please Upload To Your Youtube Channel Michael Jackson's This Is It Full Movie DVD Version And Dangerous World Tour (Live In Bucharest 1992). Reply · Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago Hello and thanks for sharing this :). I put it into my favs. Every other video that I've found of this performance is really blurry. The quality on this is really good. I love it. Reply · Jarvis Hardy 11 months ago Thank cause everyother 15 mn version is fucked damn mike was a bad motherfucker Reply · 6 Moonwalker Holly 11 months ago +Jarvis Hardy I like him bad. He's my naughty boy ;) Reply · 1 Nathan Peneha A.K.A Thepenjoker 11 months ago DopeSweet as Reply · vaibhav yadav 9 months ago I want to download michael jackson bucharest concert in HD. Please tell the source. Reply · L. Kooll 9 months ago buy it lol, its always better to have the original stuff like me, I have the original bucharest concert in DVD Reply · 1 vaibhav yadav 9 months ago +L. Kooll yes you are right. I should buy one. Reply · 1 L. Kooll 9 months ago +vaibhav yadav :) do it, you will see you wont regret it. -

Music for Guitar

So Long Marianne Leonard Cohen A Bm Come over to the window, my little darling D A Your letters they all say that you're beside me now I'd like to try to read your palm then why do I feel so alone G D I'm standing on a ledge and your fine spider web I used to think I was some sort of gypsy boy is fastening my ankle to a stone F#m E E4 E E7 before I let you take me home [Chorus] For now I need your hidden love A I'm cold as a new razor blade Now so long, Marianne, You left when I told you I was curious F#m I never said that I was brave It's time that we began E E4 E E7 [Chorus] to laugh and cry E E4 E E7 Oh, you are really such a pretty one and cry and laugh I see you've gone and changed your name again A A4 A And just when I climbed this whole mountainside about it all again to wash my eyelids in the rain [Chorus] Well you know that I love to live with you but you make me forget so very much Oh, your eyes, well, I forget your eyes I forget to pray for the angels your body's at home in every sea and then the angels forget to pray for us How come you gave away your news to everyone that you said was a secret to me [Chorus] We met when we were almost young deep in the green lilac park You held on to me like I was a crucifix as we went kneeling through the dark [Chorus] Stronger Kelly Clarkson Intro: Em C G D Em C G D Em C You heard that I was starting over with someone new You know the bed feels warmer Em C G D G D But told you I was moving on over you Sleeping here alone Em Em C You didn't think that I'd come back You know I dream in colour -

Protect the Soldiers, Dammit

candidchronicle candidchronicle candidnewspaper Vol. 2 Issue 17 | Friday, November 17, 2017 | candidchronicle.com #CandidChronicle What’s Inside? Protect The Soldiers, Dammit High Times At The Har- vest Cup- p.2 "First, second, and third places were awarded on Sunday to winning partici- pants in the best CBD con- centrate, best topical, best glass, and best hybrid flower categories as well as many more." Image and article By Benjie But for those who serve, this matic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is A 2016 report by the VA showed Cooper dedication to the protection of something that, for veterans, can that in 2014, 20 veterans died land and loved ones often comes result from exposure to graphic by suicide each day, constituting IG: @nuglifenews with a heavy price. violence, sexual harassment, and 20% of all deaths by suicides that Tommy Chong- p.4 life-threatening situations experi- year. The agency also reports that YouTube: Lucid's Vlog When William Tecumseh Sher- enced during their enlistment. veterans are at an increased risk for suicide, particularly among Despite being a relatively young man told the Michigan Military "I'm so blessed. When you're Academy graduates that 'war is The U.S. Department of Vet- males. blessed like I am, then you nation compared to much of the rest of the world, the United hell' in 1879, he was referring not erans Affairs (VA) reports the want to somehow spread States of America has become a only to the horrific and bloody percentage of soldiers experi- The VA is a federal agency and the happiness around. -

500 Drugstore Feat. Thom Yorke El President 499 Blink

500 DRUGSTORE FEAT. EL PRESIDENT THOM YORKE 499 BLINK 182 ADAMS SONG 498 SCREAMING TREES NEARLY LOST YOU 497 LEFTFIELD OPEN UP 496 SHIHAD BEAUTIFUL MACHINE 495 TEGAN AND SARAH WALKING WITH A GHOST 494 BOMB THE BASS BUG POWDER DUST 493 BAND OF HORSES IS THERE A GHOST 492 BLUR BEETLEBUM 491 DISPOSABLE HEROES TELEVISION THE DRUG OF THE OF... NATION 490 FOO FIGHTERS WALK 489 AIR SEXY BOY 488 IGGY POP CANDY 487 NINE INCH NAILS THE HAND THAT FEEDS 486 PEARL JAM NOT FOR YOU 485 RADIOHEAD EVERYTHING IN ITS RIGHT PLACE 484 RANCID TIME BOMB 483 RED HOT CHILI MY FRIENDS PEPPERS 482 SANTIGOLD LES ARTISTES 481 SMASHING PUMPKINS AVA ADORE 480 THE BIG PINK DOMINOS 479 THE STROKES REPTILIA 478 THE PIXIES VELOURIA 477 BON IVER SKINNY LOVE 476 ANIMAL COLLECTIVE MY GIRLS 475 FILTER HEY MAN NICE SHOT 474 BRAD 20TH CENTURY 473 INTERPOL SLOW HANDS 472 MAD SEASON SLIP AWAY 471 OASIS SOME MIGHT SAY 470 SLEIGH BELLS RILL RILL 469 THE AFGHAN WHIGS 66 468 THE FLAMING LIPS FIGHT TEST 467 ALICE IN CHAINS MAN IN THE BOX 466 FAITH NO MORE A SMALL VICTORY 465 THE THE DOGS OF LUST 464 ARCTIC MONKEYS R U MINE 463 BECK DEADWEIGHT 462 GARBAGE MILK 461 BEN FOLDS FIVE BRICK 460 NIRVANA PENNYROYAL TEA 459 SHIHAD YR HEAD IS A ROCK 458 SNEAKER PIMPS 6 UNDERGROUND 457 SOUNDGARDEN BURDEN IN MY HAND 456 EMINEM LOSE YOURSELF 455 SUPERGRASS RICHARD III 454 UNDERWORLD PUSH UPSTAIRS 453 ARCADE FIRE REBELLION (Lies) 452 RADIOHEAD BLACK STAR 451 BIG DATA DANGEROUS 450 BRAN VAN 3000 DRINKING IN LA 449 FIONA APPLE CRIMINAL 448 KINGS OF LEON USE SOMEBODY 447 PEARL JAM GETAWAY 446 BEASTIE -

MAT MUSTO Almost Hero, Scream Infamy, the Krays, the Shivers, and More!

STITCHED SOUND Issue #20 MAT MUSTO Almost Hero, Scream Infamy, The Krays, The Shivers, and more! 1 Fires upon fires. Not good. Yeah, so many of you have probably heard Stitched Sound is an online magazine that Issue 20 of the disastrous fire that happened in Slave brings you the latest news about upcoming Lake. It’s such a pity, and being from Alberta, I and distinguished bands. We do this through loved Slave Lake, it was just gorgeous and interviews, journalism, reviews, updates, and most of the people I encountered there were photography. Keeping the mood light and fun nothing but nice. There was also another fire is something we love to do. Whether it's up by Fort McMurray that spread insanely fast through an intriguing interview, simple update, and wide. Then today, while I was driving home or complete issue, we strive to bring you news from school, what else do I see but solid grey and updates about the fast growing music STITCHED SOUND smoke bursting up from a neighborhood? It’s scene today. crazy, and it puts a downer on the whole summer-time, bon fire thing. Plus many people Cynthia Lam have lost their homes and Anyway, that was a complete irrelevant subject, but it’s something that has been happening lately. This issue is pretty short, our shortest so far, but it’s short & sweet! Featuring the most amazing Mat Musto on the cover, and interviews with some great bands. I’m sorry that this issue is shorter, but with finals and school coming to a close, things are geting a bit stressful. -

Whyisn'ttheinternetsecureyet, Dammit?

Why Isn’t the Internet Secure Yet, Dammit? Peter Gutmann University of Auckland Introduction Standards for secure email and network communication have been around for years Every Windows desktop has S/MIME, SSL, IPsec US export controls are (effectively) gone Why isn’t the Internet secure yet? •Existing mechanisms are too hard to use •Existing mechanisms solve the wrong problem What this talk won’t cover Viruses / worms / trojan horses Buffer overflows / rootkits / IIS hacks Intrusion detection / network monitoring Spam filtering DRM / TCPA / DMCA Microsoft What this talk will cover User identification (Some aspects of) spam, along with phishing, viruses/trojans •This is a blended threat that goes beyond pure spam Credit card fraud Opportunistic encryption Key continuity management User Identification /Authentication Allow users to sign up for online information (mailing lists, web sites) •Fraudsters sign up in other people’s names –Used for DoS, not just pure fraud •Bots sign up large numbers of addresses for spam purposes Email-based Identification Use the ability to receive mail as a form of (weak) authentication •Sign up using an email address •Server sends an authenticator to the given address •Address owner responds with the authenticator to confirm the subscription Widely used for password resets, mailing list subscriptions •Good enough unless the opponent is the ISP Email-based Identification (ctd) Self-auditing via email confirmation •Attempting to use the account results in the legitimate owner being notified •Changing the email -

7SIN F Aug15:7SIN F 8/24/15 3:10 PM Page I 7SIN F Aug15:7SIN F 8/24/15 3:10 PM Page Ii

Self-Help/Humor $14.95 44 Life Lessons to Bring You Years of Glee, Passion, and Chutzpah You’ve heard it said again and again since childhood…avoid those seven deadly sins: lust, anger, pride, sloth, envy, gluttony, and greed (insert “boo-hiss” here). Oh yes, you know they’re wicked, you do your best to beat them down. But what if, just what if, you should be basking in these baddies rather than shunning them? What if a life reveling in the seven sins would bring you overwhelming happiness, never-ending fulfillment? And what if there were seven other sins that you really should be dodging? In The 7 Lively Sins, best-selling author Karen Salmansohn turns the familiar sins on their heads and dares us to indulge in them with gusto. What’s more, she unmasks the seven so-much-deadlier sins: emotional masochism, guilt, fear, repression of self-expression, need for speed, worry, and apathy. These are the real spirit-killers, so watch out for them! If they sneak into your life, you’re guaranteed a joyless future. But if you welcome those seven lively sins, well, a good time will be enjoyed by all. So be lustful! Be greedy! Be happy, dammit! KAREN SALMANSOHN is the best-selling author of How to Be Happy, Dammit; How to Make Your Man Behave in 21 Days or Less Using the Secrets of Professional Dog Trainers; and the Alexandra Rambles On series for ’tween readers. She is the founder of Glee Industries, an SALMANSOHN award-winning image consulting and book packaging firm serving clients such as MTV, KAREN Nickelodeon, Oxygen Media, and Avon. -

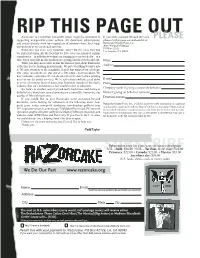

Read Razorcake Issue #48 As a PDF

RIP THIS PAGE OUT Razorcake LV D ERQD¿GH QRQSUR¿W PXVLF PDJD]LQH GHGLFDWHG WR If you wish to donate through the mail, PLEASE supporting independent music culture. All donations, subscriptions, please rip this page out and send it to: and orders directly from us—regardless of amount—have been large Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. components to our continued survival. $WWQ1RQSUR¿W0DQDJHU PO Box 42129 Razorcake has been very fortunate. Why? By the mere fact that Los Angeles, CA 90042 we still exist today. By the fact that we have over one hundred regular contributors—in addition to volunteers coming in every week day—at a time when our print media brethren are getting knocked down and out. Name What you may not realize is that the fanciest part about Razorcake is the zine you’re holding in your hands. We put everything we have into Address it. We pay attention to the pragmatic details that support our ideology. Our entire operations are run out of a 500 square foot basement. We don’t outsource any labor we can do ourselves (we don’t own a printing press or run the postal service). We’re self-reliant and take great pains E-mail WRFRYHUDERRPLQJIRUPRIPXVLFWKDWÀRXULVKHVRXWVLGHRIWKHPXVLF Phone industry, that isn’t locked into a fair weather scene or subgenre. Company name if giving a corporate donation 6RKHUH¶VWRDQRWKHU\HDURIJULWWHGWHHWKKLJK¿YHVDQGVWDULQJDW disbelief at a brand new record spinning on a turntable, improving our Name if giving on behalf of someone quality of life with each spin. Donation amount If you would like to give Razorcake some -

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE're STILL in KANSAS: the FALLACY of FEMINIST EVOLUTION in a MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell a Diss

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE’RE STILL IN KANSAS: THE FALLACY OF FEMINIST EVOLUTION IN A MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Martha Hixon, Director Dr. Will Brantley Dr. Jane Marcellus This dissertation is dedicated, in loving memory, to two dearly departed souls: to Dr. David L. Lavery, the first director of this project and a constant voice of encouragement in my studies, whose absence will never be wholly realized because of the thousands of lives he touched with his spirit, enthusiasm, and scholarship. I am eternally grateful for our time together. And to my beautiful grandmother, Fay M. Rhodes, who first introduced me to the yellow brick road and took me on her back to a pear-tree Emerald City one hundred times or more. I miss you more than Dorothy missed Kansas. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the educators who have pushed me to challenge myself, to question everything in the world around me, and to be unashamed to explore what I “thought” I already knew, over and over again. Though there are too many to list by name, know that I am forever grateful for your encouragement and dedication to learning, whether in the classroom or the world. I would like to thank my phenomenal committee for their tireless support and assistance in this project. I am especially grateful for Dr. Martha Hixon, who stepped in as my director after the passing of Dr. -

THE MILDRED HAUN REVIEW a Journal of Appalachian Literature, Culture, and Scholarship ACKNOWLEDGMENTS President, Dr

THE MILDRED HAUN REVIEW A Journal of Appalachian Literature, Culture, and Scholarship ACKNOWLEDGMENTS President, Dr. Wade McCamey Vice President for Academic Affairs, Dr. Lori Campbell Dean of Humanities, Carla Todaro Secretary to the Dean of Humanities, Debbie Wilson Secretary to the Humanities, Glenda Nolen English Department Chair, Chippy McLain All rights reserved by individual contributors. No work herein may be reproduced, copied, or transmitted by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise without the permission of the copyright owner. Mildred Haun Conference Humanities Division Walters State Community College 500 S. Davy Crockett Parkway Morristown, TN 37813-6899 http://www.ws.edu/special-events/mildred-haun/default.shtm THE MILDRED HAUN REVIEW A Journal of Appalachian Literature, Culture, and Scholarship 2014 In this issue: Editor’s Note Religious Liberty and The Mildred Haun Conference Committee members are Snake-handling Churches proud to offer this selection of some of the best presenta- by Gregory L. Bock, Ph.D. tions from this past year’s conference. The Mildred Haun Conference is dedicated to advancing literary and scholarly The Resiliant Appalachian excellence; this journal represents just a sampling of the Woman: Lesson from conference offerings. The Mildred Haun Review provides a Life and Fiction by juried selection of papers on Appalachian literature, culture, Jamie Branam Kridler, Ph.D. and scholarship. Linda M. Daugherty, M.S., ABD, and Dr. Viki Rouse, our committee chair, has worked tirelessly Terry L. Holley, B.A. to provide a quality conference for our region, and without her dedication none of this would be possible. Exploring Affrilachian Special thanks to all those who have helped make this con- Identity: ‘A Beautiful Sort ference and this journal a reality. -

Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History Summer 8-12-2013 Sit In, Stand Up and Sing Out!: Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement Michael Castellini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Recommended Citation Castellini, Michael, "Sit In, Stand Up and Sing Out!: Black Gospel Music and the Civil Rights Movement." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/76 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIT IN, STAND UP AND SING OUT!: BLACK GOSPEL MUSIC AND THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT by MICHAEL CASTELLINI Under the Direction of Dr. John McMillian ABSTRACT This thesis explores the relationship between black gospel music and the African American freedom struggle of the post-WWII era. More specifically, it addresses the paradoxical suggestion that black gospel artists themselves were typically escapist, apathetic, and politically uninvolved—like the black church and black masses in general—despite the “classical” Southern movement music being largely gospel-based. This thesis argues that gospel was in fact a critical component of the civil rights movement. In ways open and veiled, black gospel music always spoke to the issue of freedom. Topics include: grassroots gospel communities; African American sacred song and coded resistance; black church culture and social action; freedom songs and local movements; socially conscious or activist gospel figures; gospel records with civil rights themes.