Valve Types and Char

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valve Biasing

VALVE AMP BIASING Biased information How have valve amps survived over 30 years of change? Derek Rocco explains why they are still a vital ingredient in music making, and talks you through the mysteries of biasing N THE LAST DECADE WE HAVE a signal to the grid it causes a water as an electrical current, you alter the negative grid voltage by seen huge advances in current to flow from the cathode to will never be confused again. When replacing the resistor I technology which have the plate. The grid is also known as your tap is turned off you get no to gain the current draw required. profoundly changed the way we the control grid, as by varying the water flowing through. With your Cathode bias amplifiers have work. Despite the rise in voltage on the grid you can control amp if you have too much negative become very sought after. They solid-state and digital modelling how much current is passed from voltage on the grid you will stop have a sweet organic sound that technology, virtually every high- the cathode to the plate. This is the electrical current from flowing. has a rich harmonic sustain and profile guitarist and even recording known as the grid bias of your amp This is known as they produce a powerful studios still rely on good ol’ – the correct bias level is vital to the ’over-biased’ soundstage. Examples of these fashioned valves. operation and tone of the amplifier. and the amp are most of the original 1950’s By varying the negative grid will produce Fender tweed amps such as the What is a valve? bias the technician can correctly an unbearable Deluxe and, of course, the Hopefully, a brief explanation will set up your amp for maximum distortion at all legendary Vox AC30. -

Tube Number Systems

Frank's Electron tube Pages Tube Number Systems European system after 1934 Philips system before 1934 Mazda numbering system Russian numbering system Brimar type designation code Tesla numbering system European system after 1934 (pro-electron) See also: Type Designation Code from "Preferred Types of Electron Tubes 1967". 1st letter heater indication 0 tubes without filament A 4 V AC parallel connection B 180 mA DC C 200 mA AC/DC series or parallel connection D <= 1.4 V DC dry-battery, parallel connection E 6.3 V AC or carbattery, parallel connection F 13 V carbattery G 5V AC parallel connection H early: 4V DC battery. later: 150mA AC/DC series connection I 20V AC/DC parallel connection K 2 V battery O 150 mA AC/DC series connection P 300 mA AC/DC series connection U 100 mA AC/DC series connection V 50mA AC/DC series connection X 600 mA AC/DC series connection Y 450 mA AC/DC series connection 2nd+next letters tube systems A single detection diode B double detection diode C small-signal triode D power triode E small-signal tetrode (or 2nd emmission tube EE1) F small-signal pentode H hexode or heptode K octode L power pentode or power tetrode M indicator tube N thyratron Q enneode W single gasfilled rectifier diode X double gasfilled rectifier diode Y single vacuum rectifier diode Z double vacuum rectifier diode digits socket & order x P (some are V) (except U-series (e.g.UBL1), those are octal) 1x Y8A 2x W8A, Loctal (except D-series (e.g. -

Electron Optics

Chapter 5.1 Electron Optics Sol Sherr Jerry C. Whitaker, Editor-in-Chief 5.1.1 Introduction The electron gun is basic to the structure and operation of any cathode-ray device, specifically display devices. In its simplest schematic form, an electron gun may be represented by the dia- gram in Figure 5.1.1, which shows a triode gun in cross section. Electrons are emitted by the cathode, which is heated by the filament to a temperature sufficiently high to release the elec- trons. Because this stream of electrons emerges from the cathode as a cloud rather than a beam, it is necessary to accelerate, focus, deflect, and otherwise control the electron emission so that it becomes a beam, and can be made to strike a phosphor at the proper location, and with the desired beam cross section. 5.1.2 Electron Motion The laws of motion for an electron in a uniform electrostatic field are obtained from Newton’s second law. The velocity of an emitted electron is given by 1 2eV 2 v = m (5.1.1) Where: e = 1.6 × 10–19C m = 9.1 × 10–28g V = –Ex, the potential through which the electron has fallen When practical units are substituted for the values in the previous equation, the following results: 5-7 5-8 Electron Optics and Deflection No. 1 grid No. 2 grid Heater Defining aperture Figure 5.1.1 Triode electron gun structure. 1 vV=×5.93 105 2 m/s (5.1.2) This expression represents the velocity of the electron. -

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1

Vacuum Tube Theory, a Basics Tutorial – Page 1 Vacuum Tubes or Thermionic Valves come in many forms including the Diode, Triode, Tetrode, Pentode, Heptode and many more. These tubes have been manufactured by the millions in years gone by and even today the basic technology finds applications in today's electronics scene. It was the vacuum tube that first opened the way to what we know as electronics today, enabling first rectifiers and then active devices to be made and used. Although Vacuum Tube technology may appear to be dated in the highly semiconductor orientated electronics industry, many Vacuum Tubes are still used today in applications ranging from vintage wireless sets to high power radio transmitters. Until recently the most widely used thermionic device was the Cathode Ray Tube that was still manufactured by the million for use in television sets, computer monitors, oscilloscopes and a variety of other electronic equipment. Concept of thermionic emission Thermionic basics The simplest form of vacuum tube is the Diode. It is ideal to use this as the first building block for explanations of the technology. It consists of two electrodes - a Cathode and an Anode held within an evacuated glass bulb, connections being made to them through the glass envelope. If a Cathode is heated, it is found that electrons from the Cathode become increasingly active and as the temperature increases they can actually leave the Cathode and enter the surrounding space. When an electron leaves the Cathode it leaves behind a positive charge, equal but opposite to that of the electron. In fact there are many millions of electrons leaving the Cathode. -

The Development of the Vacuum Tube Creators

The Knowledge Bank at The Ohio State University Ohio State Engineer Title: The Development of the Vacuum Tube Creators: Jeffrey, Richard B. Issue Date: May-1928 Publisher: Ohio State University, College of Engineering Citation: Ohio State Engineer, vol. 11, no. 7 (May, 1928), 9-10. URI: http://hdl.handle.net/1811/34260 Appears in Collections: Ohio State Engineer: Volume 11, no. 7 (May, 1928) THE OHIO STATE ENGINEER The Development of the Vacuum Tube By RICHARD B. JEFFREY, '31 The history of the vacuum tube began with the discovery of the Edison Effect. This, like a great many other important discoveries, was an acci- dent. Edison, while experimenting with his in- candescent lamps, had placed more than one fila- output ment in the same bulb, and he noticed that if one of the filaments was held positive with respect to the other a current would flow through the bulb. He also found that this positive element, or, as it is now called, plate, did not have to be hot to sustain this current flow. This phenomenon li—- H was known for some time as a curiosity, but noth- 1 +90 to \35 ing more. Then Fleming, an English experiment- +4-5 er, noticed that if an alternating current were The screen-qrid tube (tetrode). applied to this plate the current would flow only plicated system by making use of the rectifying when the plate was positive. In other words, the properties of a crystal, notably galena. When tube acted as a rectifier, allowing the current to signals were received in this way it was the signal flow in only one direction. -

1999-2017 INDEX This Index Covers Tube Collector Through August 2017, the TCA "Data Cache" DVD- ROM Set, and the TCA Special Publications: No

1999-2017 INDEX This index covers Tube Collector through August 2017, the TCA "Data Cache" DVD- ROM set, and the TCA Special Publications: No. 1 Manhattan College Vacuum Tube Museum - List of Displays .........................1999 No. 2 Triodes in Radar: The Early VHF Era ...............................................................2000 No. 3 Auction Results ....................................................................................................2001 No. 4 A Tribute to George Clark, with audio CD ........................................................2002 No. 5 J. B. Johnson and the 224A CRT.........................................................................2003 No. 6 McCandless and the Audion, with audio CD......................................................2003 No. 7 AWA Tube Collector Group Fact Sheet, Vols. 1-6 ...........................................2004 No. 8 Vacuum Tubes in Telephone Work.....................................................................2004 No. 9 Origins of the Vacuum Tube, with audio CD.....................................................2005 No. 10 Early Tube Development at GE...........................................................................2005 No. 11 Thermionic Miscellany.........................................................................................2006 No. 12 RCA Master Tube Sales Plan, 1950....................................................................2006 No. 13 GE Tungar Bulb Data Manual................................................................. -

THE HOT-CATHODE DISCHARGE in HELIUM by Michael A. Gusinow A

The hot-cathode discharge in helium Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Gusinow, Michael Allen, 1939- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 02/10/2021 14:07:46 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319504 THE HOT-CATHODE DISCHARGE IN HELIUM by Michael A. Gusinow A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1963 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of re quirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to bor rowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED APPROVAL BY THESIS DIRECTOR This thesis has been approved on the date shown below: / Date Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express his appreciation to Dr. -

Tutorial: Adding a Control Grid to a High-Current Electron Gun

Tutorial: adding a control grid to a high-current electron gun Stanley Humphries, Copyright 2012 Field Precision PO Box 13595, Albuquerque, NM 87192 U.S.A. Telephone: +1-505-220-3975 Fax: +1-617-752-9077 E mail: techinfo@fieldp.com Internet: http://www.fieldp.com 1 Recently, I was asked to consider whether a control grid consisting of parallel or crossed wires could be added to an existing space-charge-limited electron gun for beam modulation. I identified two main questions: • Because considerable effort had been invested in the gun design, would it possible to add the grid without significantly changing the macro- scopic beam optics? • What was the contribution to the angular divergence of the beam rel- ative to the focal requirements? With regard to first question, the best approach would be to locate the wire grid at the former position of the cathode surface and to move the cathode a short distance upstream. The grid would be attached to the focus electrode bounding the former cathode surface. Figure 1 is a schematic view of the cathode-grid region. The values of D and Vc should be chosen to generate an electron current density je equal to the space-charge limited design value in the main acceleration gap. In this way, the grid surface would act almost like the original cathode, preserving the gun optics. There are two options to fabricate a grid: 1) parallel wires with spacing W or 2) a crossed grid with square openings with side length W . For a rough estimate, I did not consider the effect of the wire width. -

Pentodes Connected As Triodes

Pentodes connected as Triodes by Tom Schlangen Pentodes connected as Triodes About the author Tom Schlangen Born 1962 in Cologne / Germany Studied mechanical engineering at RWTH Aachen / Germany Employments as „safety engineering“ specialist and CIO / IT-head in middle-sized companies, now owning and running an IT- consultant business aimed at middle-sized companies Hobby: Electron valve technology in audio Private homepage: www.tubes.mynetcologne.de Private email address: [email protected] Tom Schlangen – ETF 06 2 Pentodes connected as Triodes Reasons for connecting and using pentodes as triodes Why using pentodes as triodes at all? many pentodes, especially small signal radio/TV ones, are still available from huge stock cheap as dirt, because nobody cares about them (especially “TV”-valves), some of them, connected as triodes, can rival even the best real triodes for linearity, some of them, connected as triodes, show interesting characteristics regarding µ, gm and anode resistance, that have no expression among readily available “real” triodes, because it is fun to try and find out. Tom Schlangen – ETF 06 3 Pentodes connected as Triodes How to make a triode out of a tetrode or pentode again? Or, what to do with the “superfluous” grids? All additional grids serve a certain purpose and function – they were added to a basic triode system to improve the system behaviour in certain ways, for example efficiency. We must “disable” the functions of those additional grids in a defined and controlled manner to regain triode characteristics. Just letting them “dangle in vacuum unconnected” will not work – they would charge up uncontrolled in the electron stream, leading to unpredictable behaviour. -

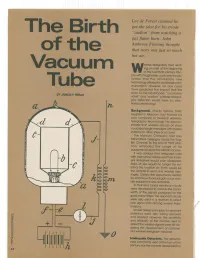

Lee De Forest Claimet\He Got the Idea for His Triode ''Audion" From

Lee de Forest claimet\he got the idea for his triode h ''audion" from wntching a gas flame bum. John Ambrose Flen#ng thought that story ·~just so much hot air. lreJess telegraphy held excit m WIng promise at the beginning of the twentieth century. Peo ~With Imagination could seethe po.. tentlal thot 'the rematkoble new technology offered forworlct1Nk:le com munfcotion. However, no one could hove predicted the impact that the soon-to-be-developed "osdllotlon volve" ond "oudlon" Wireless-telegra phy detector& wauid have on elec tronics technology. Backpouncl. Shortly before 1900, · Guglielmo Morconl had formed his own company to develop wireless telegraphy technology. He demon strated that wireless set-ups on ships eot~ld~messageswlth nearby stations on other ships or on land. t The Marconi Company hOd also j transmitted messages across the EhQ Jish Channel. By the end of 1901. Mar coni extended the range of his equipmenttospantheAtlan1tcOcean. It was obvlgus. 1hot ~raph ~MeS with subrhatlrie cables and ihelr lnber ent flmltations woUld soon disappear, Ships· at sea would no longer be iso la1ed. No locatlon on Eorth would. be too remote to send and receive mes sages. Clear1y; the opportunity existed tor enormous tiOOnciql gain once Jelio ble equlprrient was avoltable. To that end, 1Uned electrical circuits were developed to reduce the band width of the signals produced by ,the spark transrnlf'tirs. The resonont clfcults were also used in a receiver to select one signal from omong several trans missions. Slm~deslgn principles for resonont ontennas were also being explored and applied, However, the senstflvlty and reUabltlty of the devices used to ctetectthe Wireless signals were still hln cterlng the development of commer () cial wireless-telegraph nefWorks. -

Eimac Care and Feeding of Tubes Part 3

SECTION 3 ELECTRICAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS 3.1 CLASS OF OPERATION Most power grid tubes used in AF or RF amplifiers can be operated over a wide range of grid bias voltage (or in the case of grounded grid configuration, cathode bias voltage) as determined by specific performance requirements such as gain, linearity and efficiency. Changes in the bias voltage will vary the conduction angle (that being the portion of the 360° cycle of varying anode voltage during which anode current flows.) A useful system has been developed that identifies several common conditions of bias voltage (and resulting anode current conduction angle). The classifications thus assigned allow one to easily differentiate between the various operating conditions. Class A is generally considered to define a conduction angle of 360°, class B is a conduction angle of 180°, with class C less than 180° conduction angle. Class AB defines operation in the range between 180° and 360° of conduction. This class is further defined by using subscripts 1 and 2. Class AB1 has no grid current flow and class AB2 has some grid current flow during the anode conduction angle. Example Class AB2 operation - denotes an anode current conduction angle of 180° to 360° degrees and that grid current is flowing. The class of operation has nothing to do with whether a tube is grid- driven or cathode-driven. The magnitude of the grid bias voltage establishes the class of operation; the amount of drive voltage applied to the tube determines the actual conduction angle. The anode current conduction angle will determine to a great extent the overall anode efficiency. -

Series 600 Hot Cathode Bayard-Alpert Ionization Vacuum Gauges

InstruTech® Series 600 Hot Cathode Bayard-Alpert Ionization Vacuum Gauges BA600 Mini IG: Electron Bombardment (EB) degas design 1 x 10-9 to 5 x 10-2 Torr Measurement Range BA601 UHV Nude: Electron Bombardment (EB) degas design 2 x 10-11 to 1 x 10-3 Torr Measurement Range 2 BA602/BA603: Resistive degas (I R) design BA600 BA601 -10 -3 4 x 10 to 1 x 10 Torr Measurement Range Wide range of emission currents (100 μA to 10 mA) All 4 models can be degassed using electron bombardment, BA602/BA603 can also be degassed using resistive degas (I2R) BA602 BA603 Description The hot cathode Bayard-Alpert ionization vacuum gauge (IG) operates by ionizing the Collector gas inside the gauge and then measuring the number of ions generated. The ions are Filament 1 Grid then collected giving a measurement of the density or pressure of the gas inside the Filament 2 transducer. The various electrodes used in the transducer design are a collector surrounded by a circular grid with one or two filaments outside the grid. An electric current is passed through the filament to cause the filament temperature to increase. As the filament temperature is increased, electrons are emitted from the filament surface. The bias voltage between the filament and the grid will accelerate the electrons toward the grid. Most electrons will pass through the grid volume and exit the other side of the grid and then be drawn back into the grid for another traversal through the grid volume. Eventually, most electrons will impact the grid surface generating a current between the filament and the grid which is referred to as the emission current.