Moravian Geographical Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passion for Cycling Tourism

TUSCANY if not HERE, where? PASSION FOR CYCLING TOURISM Tuscany offers you • Unique landscapes and climate • A journey into history and art: from Etruscans to Renaissance down to the present day • An extensive network of cycle paths, unpaved and paved roads with hardly any traffic • Unforgettable cuisine, superb wines and much more ... if not HERE, where? Tuscany is the ideal place for a relaxing cycling holiday: the routes are endless, from the paved roads of Chianti to trails through the forests of the Apennines and the Apuan Alps, from the coast to the historic routes and the eco-paths in nature photo: Enrico Borgogni reserves and through the Val d’Orcia. This guide has been designed to be an excellent travel companion as you ride from one valley, bike trail or cultural site to another, sometimes using the train, all according to the experiences reported by other cyclists. But that’s not all: in the guide you will find tips on where to eat and suggestions for exploring the various areas without overlooking small gems or important sites, with the added benefit of taking advantage of special conditions reserved for the owners of this guide. Therefore, this book is suitable not only for families and those who like easy routes, but can also be helpful to those who want to plan multiple-day excursions with higher levels of difficulty or across uscanyT for longer tours The suggested itineraries are only a part of the rich cycling opportunities that make Tuscany one of the paradises for this kind of activity, and have been selected giving priority to low-traffic roads, white roads or paths always in close contact with nature, trying to reach and show some of our region’s most interesting destinations. -

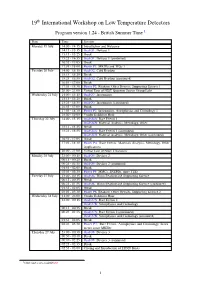

19 International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors

19th International Workshop on Low Temperature Detectors Program version 1.24 - British Summer Time 1 Date Time Session Monday 19 July 14:00 - 14:15 Introduction and Welcome 14:15 - 15:15 Oral O1: Devices 1 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O1: Devices 1 (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:00 Poster P1: MKIDs and TESs 1 Tuesday 20 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O2: Cold Readout 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O2: Cold Readout (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P2: Readout, Other Devices, Supporting Science 1 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Quantum Sensor Group Labs Wednesday 21 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O3: Instruments 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O3: Instruments (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P3: Instruments, Astrophysics and Cosmology 1 18:00 - 19:00 Vendor Exhibitor Hour Thursday 22 July 14:00 - 15:15 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other 15:15 - 15:25 Break 15:25 - 16:55 Oral O4A: Rare Events 1 (continued) Oral O4B: Material Analysis, Metrology, Other (continued) 16:55 - 17:05 Break 17:05 - 18:30 Poster P4: Rare Events, Materials Analysis, Metrology, Other Applications 20:00 - 21:00 Virtual Tour of NIST Cleanoom Monday 26 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O5: Devices 2 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O5: Devices 2 (continued) 01:55 - 02:05 Break 02:05 - 03:30 Poster P5: MMCs, SNSPDs, more TESs Tuesday 27 July 23:00 - 00:15 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science 00:15 - 00:25 Break 00:25 - 01:55 Oral O6: Warm Readout and Supporting Science -

Transience10

a publication of ADVENTURE CYCLING ASSOCIATION AN EPIC ACT OF TRANSIENCE10 $6.95 OCT/NOV 2019 Vol.46 No.8 STACK LONG DAYS. CLIMB LIKE A MOUNTAIN GOAT. Saddle, back, neck and wrist pain no longer get a say in your plans. Our patented drive system brings together the best of traditional and recumbent touring bikes so you don’t have to sacrifice performance for comfort. But we should warn you, your cheeks may hurt from smiling. Adventure Cyclist readers get $100 off the Cruzbike of their choice Use code: ADVENTURE at C ruzbike.com Letter from the Editor online WHAT YEAR IS IT AGAIN? Revolution, evolution, and the march of progress PHOTO CONTEST OPEN NOW ➺I recently found myself standing on a quiet main ’Tis the season for submitting street in front of a small-town Montana theater. I’d your best images to the 11th been on the road for a while and small towns can start Annual Bicycle Travel Photo to look the same, but when I looked up at the marquee Contest. Winning images are published in the May 2020 and saw “Lion King,” for a moment I was sure of EDGERTONADAM neither where I was nor when. Adventure Cyclist, plus these Depending on the level of charity you’re inclined shots appear in our annual to employ, there are either no more ideas left, or we calendar. Send us your best simply evolve the same core idea over and over to at adventurecycling.org/ reintroduce it to new generations. I was certainly thinking about the photcontest now through spectrum of “invention” as I read Bob Marr’s story on page 20 about turn- November 30. -

The Future of NATO and European Defence

House of Commons Defence Committee The future of NATO and European defence Ninth Report of Session 2007–08 Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 4 March 2008 HC 111 [Incorporating HC 707-i & ii] Published on 20 March 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 The Defence Committee The Defence Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Ministry of Defence and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon James Arbuthnot MP (Conservative, North East Hampshire) (Chairman) Mr David S Borrow MP (Labour, South Ribble) Mr David Crausby MP (Labour, Bolton North East) Linda Gilroy MP (Labour, Plymouth Sutton) Mr David Hamilton MP (Labour, Midlothian) Mr Mike Hancock MP (Liberal Democrat, Portsmouth South) Mr Dai Havard MP (Labour, Merthyr Tydfil and Rhymney) Mr Adam Holloway MP (Conservative, Gravesham) Mr Bernard Jenkin MP (Conservative, North Essex) Mr Brian Jenkins MP (Labour, Tamworth) Mr Kevan Jones MP (Labour, Durham North) Robert Key MP (Conservative, Salisbury) John Smith MP (Labour, Vale of Glamorgan) Richard Younger-Ross MP (Liberal Democrat, Teignbridge) The following Members were also Members of the Committee during the Parliament. Mr Colin Breed MP (Liberal Democrat, South East Cornwall) Derek Conway MP (Conservative, Old Bexley and Sidcup) Mr Mark Lancaster MP (Conservative, North East Milton Keynes) Willie Rennie MP (Liberal Democrat, Dunfermline and West Fife) Mr Desmond Swayne MP (Conservative, New Forest West) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. -

Instruction Manual

DCP551 Mark ΙΙ Digital Control Programmer User’s Manual EN1I-6186 Issue 11 (11/06) WARRANTY The Honeywell device described herein has been manufactured and tested for corrent operation and is warranted for a period of one year. TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE If you encounter a problem with your unit, please review all the configuration data to verify that your selections are consistent with your application; (i.e. Inputs, Outputs, Alarms, Limits, etc.). If the problem persists after checking the above parameters, you can get technical assistance by calling the following: In the U.S.A. •••••••••••••1-800-423-9883 In Europe ••••••••••••••••Your local branch office Safety Precautions ■ About Symbols Safety precautions are for ensuring safe and correct use of this product, and for pre- venting injury to the operator and other people or damage to property. You must observe these safety precautions, which are indicated by various symbols in this manual. Read the safety precautions first and make sure you understand them before you read the rest of the manual. WARNING Warnings indicate a situation which, if not avoided, could result in death or serious injury. CAUTION Cautions indicate a situation which, if not avoided or handled correctly, may result in injury or property damage. ■ Example of Symbols Equilateral triangles alert the user to a possible danger “WARNING” or “CAUTION” that may be caused by wrongful operation or misuse of this product. The symbol inside the triangle graphically represent the actual danger. (The example on the left warns the user of the danger of electric White circles with a 45° slash angled downward from upper left to lower right notifies the user that specific actions are prohibited to prevent possible danger. -

The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe

The Archaeological Sites of The Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums 0 The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums Preparers: - Dr Salah Mohamed Ahmed - Dr Derek Welsby Preparer (Consultant) Pr. Henry Cleere Team of the “Draft” Management Plan Dr Paul Bidwell Dr. Nick Hodgson Mr. Terry Frain Dr. David Sherlock Management Plan Dr. Sami el-Masri Topographical Work Dr. Mario Santana Quintero Miss Sarah Seranno 1 Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………. 5 1- Identification of the Property………………………………………………… 8 1. a State Party……………………………………………………………………… 8 1. b State, Province, or Region……………………………………………………… 8 1. c Name of Property………………………………………………………………. 8 1. d Geographical coordinates………………………………………………………. 8 1. e Maps and plans showing the boundaries of the nominated site(s) and buffer 9 zones…………………………………………………………………………………… 1. f. Area of nominated properties and proposed buffer zones…………………….. 29 2- Description…………………………………………………………………………. 30 2. a. 1 Description of the nominated properties………………………………........... 30 2. a. 1 General introduction…………………………………………………… 30 2. a. 2 Kushite utilization of the Keraba and Western Boutana……………… 32 2. a. 3 Meroe…………………………………………………………………… 33 2. a. 4 Musawwarat es-Sufra…………………………………………………… 43 2. a. 5 Naqa…………………………………………………………………..... 47 2. b History and development………………………………………………………. 51 2. b. 1 A brief history of the Sudan……………………………………………. 51 2. b. 2 The Kushite civilization and the Island of Meroe……………………… 52 3- Justification for inscription………………………………………………………… 54 …3. a. 1 Proposed statement of outstanding universal value …………………… 54 3. a. 2 Criteria under which inscription is proposed (and justification for 54 inscription under these criteria)………………………………………………………… ..3. -

Aktualisieren Rowerem Z Danii Do Krajów Nadbałtyckich

Dänemark Oldenburg in Holstein Insel Poel (Rundweg ca. 27 km) Saal Das ehemalige Zisterzienserkloster Hilda Überreste der gotischen Stadtmauer und Dania wowa budowla jest jednym z najstarszych 47 m zwieńczona jest ośmiobocznym heł- wyburzeniu wieży zachodniej, wybudowa- Kemnitz Szwecji i Norwegii, który spędził w nim Die St.-Johannis-Kirche (Dom) wurde Die romanisch-gotische Dorfkirche in Mit der Errichtung der Dorfkirche (später Eldena) wurde um 1200 gegründet. diente als Klosterkirche der seit 1277 hier ceglanych kościołów Europy Północnej i mem nazywanym »biskupią czapką«, jest no zachodnie przęsło z oknami zakończony- Kościół św. Krzyża to sześcioprzęsło- schyłek swojego życia w latach 1449–59. 9 14 21 30 Haderslev 1156–1160 vom letzten Oldenburger Kirchdorf wurde im 13. Jh. errichtet. wurde um 1300 begonnen. Der back- Bis ca. 1245 entstanden die ältesten erhal- ansässigen Zisterzienserinnen. Ein weiterer Haderslev znaczącym przedstawicielem ceglanych romańska. Wnętrze kryje m.in. dwa cenne mi okrągłymi łukami. Inwentarz kościoła wa prostokątna budowla z prostym Najważniejszą sakralną budowlą miasta Wenn Sie mit einem Segelboot Ihre Bischof Gerold als romanische Basilika Später im 13. und 14. Jh. folgten mehrere steingotische Hallenbau weist am ehem. tenen Bauteile der Kloster kirche. Nach backsteingotischer Anziehungspunkt ist Jeśli chcą Państwo rozpocząć swój rajd romańskich budowli. Wyposażenie wnętrza skrzydłowe ołtarze (pocz. XV w. I 1500 r.). jest w znacznej mierze barokowy. Jedynie zwieńczeniem chóru z XIV w. Godny uwa- jest Kościół Mariacki (XIV w.), ogromna 1 Radtour beginnen möchten, können 1 erbaut. Der dreischiffige Bau ist eine der Umbauten. Im 19. Jh. kam die Südvorhalle Chorportal sowie am Nordportal reiche Plünderungen im Dreißig jährigen Krieg u. -

13589 Covers CR:Layout 2

Editors: Lori Tamura FOR MORE INFORMATION Arthur Robinson Elizabeth Moxon Julie McCullough For information about using the ALS, contact Design, layout, photography, and additional writing provided by the Creative Services Office and the Communications Department Jeffrey Troutman of Berkeley Lab’s Public Affairs Department. User Services Administrator Advanced Light Source The editors gratefully acknowledge the ALS users and staff for their contributions, advice, and patience. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory MS 6R2100 Berkeley, CA 94720-8226 Tel: (510) 495-2001 Fax: (510) 486-4773 Email: [email protected] ALS home page http://www-als.lbl.gov/ Disclaimer This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor The Regents of the University of Cali- fornia, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manu- facturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or The Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or The Regents of the Univer- sity of California. Available to DOE and DOE Contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Communication, P.O. -

Ciclovie Nel Veneto

BOZZA – Work in progress Ciclovie nel Veneto Versione 20181120 Volker SCHMIDT Padova, Italy mailto:[email protected] cellulare: +39-340-1427105 ATTENZIONE: Il materiale è destinato esclusivamente ad uso personale e non-commerciale.. Scritto con OpenOffice.org Writer Ciclovie nel Veneto - Slide 1 Contenuto Introduzione .............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Vista d'insieme .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Le Ciclovie in Veneto ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 1 Gli Itinerari della REV ....................................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 1.1 I1 - Dal Lago di Garda a Venezia ............................................................................................................................................................................... 9 1.2 I2 - L'anello del Veneto ........................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Route Report Eurovelo Route 7 Middle Europe Route Or the Sun Route

Route report EuroVelo Route 7 Middle Europe Route or The Sun Route December 2004 Jens Erik Larsen De Frie Fugle Denmark Content 0. About the route and EuroVelo 1. Norway and Finland 1.1 General overview 1.2 Route description 1.3 Technical facts 1.4 Further information - maps and guides 1.5 Contacts 2. Sweden 2.1 General overview 2.2 Route description 2.3 Technical facts 2.4 Further information - maps and guides 2.5 Contacts 3. Denmark 3.1 General overview 3.2 Route description 3.3 Technical facts 3.4 Further information - maps and guides 3.5 Contacts 4. Germany 4.1 General overview 4.2 Route description 4.3 Technical facts 4.4 Further information - maps and guides 4.5 Contacts 5. Czech Republic 5.1 General overview 5.2 Route description 5.3 Technical facts 5.4 Further information - maps and guides 5.5 Contacts 6. Austria 6.1 General overview 6.2 Route description 6.3 Technical facts 6.4 Further information - maps and guides 6.5 Contacts 7. Italy 7.1 General overview 7.2 Route description 7.3 Technical facts 7.4 Further information - maps and guides 7.5 Contacts 8. Malta 8.1 General overview 8.2 Route description 8.3 Technical facts 8.4 Further information - maps and guides 8.5 Contacts Conclusion/overview 2 Colofon This Route report has been prepared with funding from: Danish Tourist Board - www.visitdenmark.dk City of Copenhagen - www.vejpark.kk.dk/byenstrafik/cyklernesby Turisme region syd/Østdansk Turisme - www.visiteastdenmark.dk De Frie Fugle Denmark - www.friefugle.dk FIAB/Cyclists Federation of Italy - www.fiab-onlus.it Frontpage Photo: Thanks to Sissel Jenseth Norway 3 0. -

Roundabout Nov 2017

The Cotteridge Church Witnessing at the Heart of the Community November 2017 Mike’s Message The season of Remembrance and Hope It’s November. The year is already drawing towards its close. Within a week or so of this magazine being published the German Christmas Market will be open in the City Centre. Christmas seems to sneak up on us earlier each year. But there’s a lot to do before then. November starts with a time of remembering. It’s a time when the Church has traditionally thought, during the season of All Saints and All Souls, of those who have died. Then comes Remembrance, as we recall those who have died in conflict; long ago, more recently and in current combat. Next year, in 2018, Remembrance Sunday will fall on 11th November itself, exactly 100 years since the Armistice that brought the First World War towards it’s end at the Treaty of Versailles in 1919. As November draws to its close we will still have that beautiful and reflective season of Advent ahead of us. Advent is very short this year, as the Fourth Sunday of Advent is Christmas Eve. We’ll be holding a Study Group during Advent but, to get four sessions in, we’ll be starting early. Join us on Tuesdays at 11.00am (28th November, 5th, 12th and 19th December) as we ask ‘So what are you waiting for?’ It looks at time and our attitude towards it. In Advent we not only look back through time to the birth of Jesus at Bethlehem, but also look forward towards his return at the end of time. -

Agenda and Meeting Notice

Board Members Ron Roberts, Chair Chair, County of San Diego Terry Sinnott, First Vice Chair Deputy Mayor, Del Mar Matt Hall Mayor, Carlsbad Mary Salas Mayor, Chula Vista BOARD OF DIRECTORS Carrie Downey Councilmember, Coronado Bill Wells AGENDA Mayor, El Cajon Lisa Shaffer Deputy Mayor, Encinitas Friday, February 12, 2016 Sam Abed Mayor, Escondido Serge Dedina Please Note Meeting Time Mayor, Imperial Beach 9 a.m. to 12 noon Kristine Alessio Councilmember, La Mesa Mary Teresa Sessom SANDAG Board Room Mayor, Lemon Grove 401 B Street, 7th Floor Ron Morrison Mayor, National City San Diego Jim Wood Mayor, Oceanside Steve Vaus Mayor, Poway Kevin Faulconer Mayor, City of San Diego Todd Gloria AGENDA HIGHLIGHTS Councilmember, City of San Diego Jack Dale Councilmember, Santee • POTENTIAL FUNDING MEASURE: UPDATE AND Jim Desmond Mayor, San Marcos INITIAL DRAFT EXPENDITURE PLAN Lesa Heebner ALTERNATIVES Councilmember, Solana Beach Judy Ritter Mayor, Vista PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC DEVICES DURING THE MEETING Dianne Jacob Vice Chair, County of San Diego Advisory Members YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS Hon. John Renison MEETING BY VISITING OUR WEBSITE AT SANDAG.ORG Supervisor, District 1 Imperial County Malcolm Dougherty, Director MESSAGE FROM THE CLERK California Department In compliance with Government Code §54952.3, the Clerk hereby announces that the compensation of Transportation for legislative body members attending the following simultaneous or serial meetings is: Executive Harry Mathis, Chair Committee (EC) $100, Board of Directors (BOD) $150, and Regional Transportation Commission (RTC) Metropolitan Transit System $100. Compensation rates for the EC and BOD are set pursuant to the SANDAG Bylaws and the Mark Packard, Chair North County Transit District compensation rate for the RTC is set pursuant to state law.