29. the Royal School Dungannon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

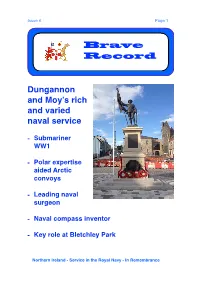

Brave Record Issue 6

Issue 6 Page !1 Brave Record Dungannon and Moy’s rich and varied naval service - Submariner WW1 - Polar expertise aided Arctic convoys - Leading naval surgeon - Naval compass inventor - Key role at Bletchley Park Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !2 Moy man may be Northern Ireland’s first submariner loss HM Submarine D5 was lost on 03/11/1914. In the ship was 29 year old Fred Bradley. He had previously served during the Boer War. He had also served in HMS Hyacinth in the Somali Expedition. HMS D5 was a British D class submarine built by Vickers, Barrow. D5 was laid down on 23/2/1910, launched 28/08/1911 and was commissioned 19/02/1911. One source states she was sunk by a German mine laid by SMS Stralsund after responding to a German attack on Yarmouth by cruisers. The bombardment, which was very heavy and aimed at the civilian population, was rather ineffective, due to the misty weather and only a few shells landed on the beaches at Gorleston. In response, the submarines D3, E10 and D5 - the latter being under the command of Lt.Cdr. Godfrey Herbert, were ordered out into the roadstead to intercept the enemy fleet. Northern Ireland - Service in the Royal Navy - In Remembrance Issue 6 Page !3 Another source states HMS D5 was sunk by a British mine two miles south of South Cross Buoy off Great Yarmouth in the North Sea. 20 officers and men were lost. There were only 5 survivors including her Commanding Officer. -

Briefing Notes for Education Committee 15 October 2014 Colin

Briefing Notes for Education Committee 15th October 2014 Colin Knox and Vani Borooah Definitions Difference between shared education and integrated education: Shared Education Shared Education encompasses a number of different types of sharing, from projects and shared classes through to shared education models, such as those defined in the Bain report (eg: Federations/Confederations; Shared Campus and Shared Faith schools). Under Article 64 (1) of The Education Reform (NI) Order 1989, integrated education is defined as “the education together at school of Protestant and Roman Catholic pupils (Minister of Education) The Terms of Reference for the Ministerial Advisory Group on Advancing Shared Education defined Shared Education as: The organisation and delivery of education so that it: meets the needs of, and provides for the education together of, learners from all Section 75 categories and socio-economic status; involves schools and other education providers of differing ownership, sectoral identity and ethos, management type or governance arrangements; and delivers educational benefits to learners, promotes the efficient and effective use of resources, and promotes equality of opportunity, good relations, equality of identity, respect for diversity and community cohesion (MAG Report) By its nature, Shared Education involves more than one school type. This view has been endorsed by the Ministerial Advisory Group, which further refined the definition to “...involves two or more schools or other education institutions from different sectors -

Department of Education

24 January 2012 AQW 6153/11-15 Trevor Lunn has asked: To ask the Minister of Education to list the schools which can hold the pupil numbers recommended in the Bain Report, broken down by school type. In the Report of the Independent Strategic Review of Education (the Bain Report) it was recommended that the minimum enrolments for new primary schools (Years 1-7) should be 140 pupils in urban areas and 105 pupils in rural areas and for Years 8-12 in new post primary schools should be 500 pupils. It was recommended that the minimum enrolment for a new sixth form in an 11-18 school should be 100 pupils. The Department’s sustainable schools policy classifies schools located within the Belfast and Derry District Council areas as urban. Schools located in other areas are considered rural. Schools which have an approved enrolment number in 2011/12 that falls within the recommended minimum enrolments are detailed below. Urban Primary Schools Controlled Ashlea Primary School Avoniel Primary School Ballygolan Primary School Ballysillan Primary School Belmont Primary School Blackmountain Primary School Blythefield Primary School Botanic Primary School Carr's Glen Primary School Cavehill Primary School Cumber Claudy Primary School Currie Primary School Donegall Road Primary School Drumahoe Primary School Dundela Infants School Ebrington Controlled Primary School Edenbrooke Primary School Eglinton Primary School Elmgrove Primary School Euston Street Primary School Fane Street Primary School Finaghy Primary School Forth River Primary School Fountain Primary School Glenwood Primary School Greenhaw Primary School Greenwood Primary School Harding Memorial Primary School Harmony Primary School Knocknagoney Primary School Ligoniel Primary School Londonderry Model Primary School Lowwood Primary School Malvern Primary School Nettlefield Primary School Newbuildings Primary School Orangefield Primary School Rosetta Primary School Seaview Primary School, Belfast. -

MUDC601 Copy Of

MUDC601 STATEMENT OF COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT (SCI) FOR THE NEW MID ULSTER LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2030 AND DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT FUNCTIONS May 2016 1 CONTENTS 1.0 What is the purpose of the Statement of Community Involvement? 1.1 Purpose of the Statement 1.2 Vision of Participation 1.6 Principles of Community Involvement 2.0 Local Community Involvement in the preparation of the Mid Ulster Local Development Plan 2030 2.1 Purpose and Structure of the Local Development Plan 2.8 Who can get Involved? 2.10 Empowering disadvantaged and under-represented groups 2.13 How and when will the community be involved? 2.14 Developing an Evidence Base 2.15 Preferred Options Paper 2.17 Publication of Draft Plan Strategy 2.18 Public Inspection of Representations 2.19 Independent Examination 2.20 Adoption of Plan Strategy 2.21 Local Policies Plan 2.22 Public Inspection of Representations 2.23 Independent Examination 2.24 Adoption of Local Policies Plan 2.25 Next Steps 3.0 Local Community Involvement in Mid Ulster Development Management Functions 3.1 Purpose 3.3 Pre-Application Discussions (PAD’s) 3.4 Pre-Application Community Consultation (PACC) 3.7 Application Stage 3.8 Advertising 3.10 EIA Development 2 3.12 Neighbour Notification 3.15 Obtaining Further Information and getting involved in planning applications 3.16 Public Register 3.17 File Inspection 3.18 Submitting Comments 3.27 Community Involvement at the Planning Committee Stage 3.28 Pre-determination hearings and speaking at the Planning Committee 3.30 Community Involvement after a Planning Application -

Report on the 31 March 2019 Actuarial Valuation

Report on the 31 March 2019 actuarial valuation Local Government Pension Scheme (Northern Ireland) Prepared for Northern Ireland Local Government Officers' Superannuation Committee as Scheme Manager of LGPS (NI) Prepared by Aon 2019 30 March 2020 At a glance Past Service Position Shorthand There was a surplus of £836.9M relative to the liabilities. The funding level was 112%. Funding level: the value of assets held by the Fund divided by the liabilities. Funding target (liabilities): the level of assets determined by the Committee as being appropriate to meet member benefits, assuming the Fund continues indefinitely. Future service rate: the employer share of the cost of benefits being earned in future, expressed as a percentage of pensionable pay. The figure quoted is a weighted average of all employers' future service rates. Pensionable Pay: as defined in the Regulations in Employer Contributions relation to post-2015 membership. % of 2019 valuation 2016 valuation Recovery period: the period over which any surplus or Pensionable Pay shortfall is eliminated. Future service rate 20.7% 19.3% Past service rate: the adjustment to the future service Past service rate (4.3)% 1.7% rate, expressed as a % of pensionable pay, needed to Allowance for possible cost 3.2%* n/a restore the funding level of the Fund as a whole to 100% over the recovery period, if the membership is broadly of McCloud / Cost Cap stable and pay increases and other assumptions are as Total rate 19.6% 21.0% assumed. This adjustment is negative when the Fund is in Recovery period 20 years from 1 April 2020 20 years from 1 April 2017 surplus. -

Admissions Criteria

GBA News - 20th January 2021 Chairperson's Message Dear member school, I trust and hope that you are keeping well in these extremely challenging times. Unfortunately, the start of 2021 appears to be just as turbulent as 2020 as our schools continue to provide remote learning and much needed support for vulnerable children and the children of key workers. The challenges brought about by the pandemic continue to arise. As we have witnessed in the past, and particularly in the last year, our schools do adapt and deliver, even in the most challenging of circumstances. The GBA staff continue to work remotely on your behalf. If you have any issues that you wish to raise please contact Nuala or Helen. I place on record my thanks for your continued leadership and dedication to the education of our young people. With best wishes for the New Year, Jacqueline Weir GBA Chairperson Admissions Criteria Recent days have seen animated discussion and varied suggestions about admissions criteria. It is unsurprising that the GBA, as the representative body for 50 Voluntary Grammar Schools, should seek to uphold the Voluntary Principle which is central to each school’s identity and individual ethos. A defining feature of the Voluntary Principle is the duty of each Board of Governors to determine its Year 8 admissions criteria. The GBA represents a range of schools. Some have an academic component in their admissions criteria; some apply academic criteria to determine a proportion of their intake and others make no use of such criteria. In each school, regardless of any specific criterion, it is Governors’ responsibility to ensure the criteria are kept under review and are legally compliant. -

Northern Ireland

List of Schools in Northern Ireland This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar School Newry Mourne and Down 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Abbey Community College Antrim and Newtownabbey 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints College Belfast 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG Antrim Grammar School Antrim and -

Registration Form and Guidance Notes for Common Entrance Assessment

Association for Quality Education Limited Registration Form and Guidance Notes for Common Entrance Assessment CLOSING DATE FOR APPLICATIONS: 11 SEPTEMBER 2015 The schools listed below are entitled to use the Common Entrance Assessment in their admissions process. Please complete this form to register your child for the Common Entrance Assessment. North-Eastern Area Belfast Area Antrim Grammar School Belfast Royal Academy Ballyclare High School Bloomfield Collegiate Grammar School Ballymena Academy Campbell College Belfast High School Grosvenor Grammar School Cambridge House Grammar School Hunterhouse College Carrickfergus Grammar School Methodist College Belfast Coleraine Grammar School Royal Belfast Academical Institution Dalriada School, Ballymoney Strathearn School Larne Grammar School Victoria College Wellington College Western Area South Eastern Area Collegiate Grammar School, Bangor Grammar School Enniskillen Foyle College Down High School Friends’ School, Lisburn Limavady Grammar School Glenlola Collegiate School Omagh Academy Regent House School Portora Royal School Sullivan Upper School Strabane Academy The Wallace High School Southern Area Banbridge Academy The Royal School, Armagh The Royal School, Dungannon Any child entering P7 in 2015 who wishes to apply to any of the schools listed above should sit the Common Entrance Assessment (CEA). It is the responsibility of parents to ensure that the CEA registration form is completed. Please read the instructions carefully before completing the form. - 1 - AQE Office, Unit 3, Weavers Court Business Park, BELFAST BT12 5GH Tel: 028 9022 4002 Email: [email protected] www.aqe.org.uk Guidance Notes Guidance Notes Filling in the Form Use black ink only. Write clearly in BLOCK CAPITALS. Attach three recent passport size photographs of your child for identification purposes and write the full name of your child on the back of each photograph. -

![CCEA Consultation on Proposed Changes 2021 [FINAL DRAFT] V2 for Design, with Queries 14-09-DESIGN-VERSION-Trackaccept](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9322/ccea-consultation-on-proposed-changes-2021-final-draft-v2-for-design-with-queries-14-09-design-version-trackaccept-2619322.webp)

CCEA Consultation on Proposed Changes 2021 [FINAL DRAFT] V2 for Design, with Queries 14-09-DESIGN-VERSION-Trackaccept

CONSULTATION ON PROPOSED CHANGES TO CCEA GCSE, AS AND A LEVEL QUALIFICATIONS FOR SUMMER 2021 Consultation Findings on Proposed Changes to CCEA GCSE, AS and A Level Qualifications for Summer 2021 First published 9 October 2020 i Consultation Findings on Proposed Changes to CCEA GCSE, AS and A Level Qualifications for Summer 2021 CONTENTS Introduction 2 Methodology 3 Background 3 Consultation Arrangements 3 Results 4 Demographics 4 Public Health Adaptations 7 Specification Order 8 AS and A Level Assessment Arrangements 10 Changes to Assessment at GCSE 13 GCSE English Language and Mathematics 20 Equality 22 Additional Comments 24 Conclusions 25 Appendices 27 Appendix 1 List of Respondent Organisations 27 Appendix 2 Split Response 31 Appendix 3 Subject-Specific Feedback 40 First published 9 October 2020 1 Consultation Findings on Proposed Changes to CCEA GCSE, AS and A Level Qualifications for Summer 2021 Introduction The disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures has been felt by learners across Northern Ireland. The pandemic has caused many difficulties for young people, including the loss of face-to-face teaching and social interaction, pressure on mental wellbeing and, in some cases, the difficulties of bereavement. The Department of Education has put in place a range of different interventions to support children and young people (as well as school leaders and teachers) in these unique circumstances. It also commissioned CCEA to look at how best to adapt qualifications during 2020/21 to take account of current public health requirements, lost learning time, potential further disruption and, above all, to reduce the burden of assessment on students. -

Registration Form to Allow Parents to Register Their Children in a Way Which Can Be Processed Immediately by Staff at Home

REGISTRATION DURING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC AQE staff are currently working from home with limited access to the AQE Office. We have provided an online registration form to allow parents to register their children in a way which can be processed immediately by staff at home. Please consider using the online form, which can be found at www.aqe.org.uk. Any form submitted by post to the AQE Office, will be processed as soon as possible but will experience delays due to the current circumstances. We are not accepting forms by hand delivery to the office at this current time. While all forms will be processed, Admissions Cards will not be posted out to any candidates until such times at the office can safely re-open to all AQE staff. Please be aware that in the event of the assessments being cancelled by AQE, the fee will be partially refunded (£20). The remaining £35 is non-refundable. AQE Association for Quality Education Limited Registration Form & Guidance Notes for the Common Entrance Assessment For children entering Primary 7 in September 2020 who wish to apply to any of the schools listed below. Opening Date of Registration: Thursday 14th May 2020 from 9am Final Date for Registration Forms: Friday 25th September 2020 at 4pm This form MUST be completed to register your child for the Common Entrance Assessment. Confirmation of your registration will be in the form of your child’s Admission Card. Please note it can take 4 WEEKS for registration forms to be processed and Admissions Cards issued to parents. -

Voluntary Grammar Schools (Post Primary)

Voluntary Grammar Schools (Post Primary) Revised Formula Funding Budgets 201617 (including 'ASB Addition') DE ASB Budget Revised Total School Reference School Name Addition Share formula funding Type Number 201617 201617 5420059 VGS Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar, Newry 25,508 3,971,142 1420277 VGS Aquinas Diocesan Grammar, Belfast 22,983 3,548,535 4420086 VGS Assumption Grammar, Ballynahinch 23,595 3,707,055 3420011 VGS Ballymena Academy 34,512 5,251,229 4420015 VGS Bangor Grammar School 24,504 3,815,273 3420077 VGS Belfast High School 25,744 3,924,873 1420028 VGS Belfast Royal Academy 40,034 6,186,289 1420020 VGS Campbell College, Belfast 25,632 4,129,420 2420064 VGS Christian Brothers' Grammar, Omagh 27,712 4,262,568 3420317 VGS Coleraine Grammar 41,766 6,542,894 3420012 VGS Dalriada School, Ballymoney 24,670 3,783,415 1420082 VGS Dominican College, Belfast 28,979 4,496,058 3420068 VGS Dominican College, Portstewart 13,642 2,157,295 2420229 VGS Foyle College, Londonderry 23,115 3,631,173 4420050 VGS Friends' School, Lisburn 28,739 4,416,780 1420265 VGS Hunterhouse College, Belfast 19,695 3,115,167 3420046 VGS Larne Grammar School 20,753 3,241,662 3420034 VGS Loreto College, Coleraine 22,778 3,532,866 2420065 VGS Loreto Grammar, Omagh 24,933 3,829,783 2420287 VGS Lumen Christi College, Londonderry 24,130 3,746,658 1420022 VGS Methodist College, Belfast 51,629 7,855,123 2420041 VGS Mount Lourdes Grammar, Enniskillen 21,818 3,476,101 4420259 VGS Our Lady and St Patrick's College Belfast 35,875 5,451,493 5420060 -

Download Northern Ireland Visitor List

School/college name Post code Visitors 3D Morden College SE1 7SP 10 Abbey Christian Brothers' Grammar School, Newry BT34 1QN 130 Abbey Community College BT36 0EA 20 Aquinas Diocesan Grammar School. Belfast BT6 0BY 120 Ashfield Girls' High School, Belfast BT4 2LY 54 Assumption Grammar School BT248EA 107 Ballyclare High School 152 Bangor Academy and Sixth Form College BT20 4TB 100 Belfast Boys' Model School, Belfast BT14 6RB 75 Belfast High School BT37 0PX 115 Belfast Metropolitan College 120 Belfast Metropolitan College, Millfield BT24 7AY 15 Belfast Royal Academy BT14 6JL 210 Bloomfield Collegiate School BT5 6HW 90 Campbell College BT4 2ND 45 Carndonagh Community School F93VK61 42 Carrickfergus College BT387QX 80 Carrickfergus Grammar School BT38 7RA 100 Coleraine Grammar School BT51 3 LA 100 Cross & Passion College BT54 6LA 52 Cullybackey College BT42 1BP 50 Dalriada School BT53 6BL 125 De La Salle College BT118LT 118 Devenish College BT74 6JL 33 Drumragh College BT790GW 50 Dunclug College BT43 6SU 60 Enniskillen Royal Grammar School, Cooper Crescent BT74 6DQ 130 Fivemiletown College BT75 0SB 41 Glenlola Collegiate School BT20 4TH 140 Holy Trinity College, Cookstown BT80 8QB 110 Hunterhouse College BT10 OLE 76 Integrated College Dungannon BT716LS 62 Kilkeel High School BT34 4BP 60 Kilskeery Independent Christian School BT78 3RN 9 Larne Grammar School BT40 1PQ 100 Limavady Grammar School BT499ET 100 Limavady High School BT49 9AN 45 Lismore Comprehensive School, Craigavon BT655DU 177 Lisneal College BT47 5AD 25 Loreto Grammar School, Omagh BT781DL 139 Lurgan College BT66 6JW 117 Magherafelt High School BT456AF 40 Malone College BT10 0JB 70 Methodist College BT9 6BY 292 Monaghan Collegiate School IE 50 North West Regional College, Derry BT49 OEX 86 Northern Regional College BT52 1QA 200 Oakgrove Integrated College BT47 6TG 54 Our Lady and Saint Patrick's College BT5 7DL 175 Our Lady's Grammar School BT35 6DY 130 Parkhall Integrated College BT411AF 48 Portadown College BT63 5BU 100 Priory Integrated College, Co.