Researching the Underground Railroad in Delaware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African American Literature in Transition, 1850–1865

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42748-7 — African American Literature in Transition Edited by Teresa Zackodnik Frontmatter More Information AFRICAN AMERICAN LITERATURE IN TRANSITION, – The period of – consists of violent struggle and crisis as the United States underwent the prodigious transition from slaveholding to ostensibly “free” nation. This volume reframes mid-century African American literature and challenges our current understand- ings of both African American and American literature. It presents a fluid tradition that includes history, science, politics, economics, space and movement, the visual, and the sonic. Black writing was highly conscious of transnational and international politics, textual circulation, and revolutionary imaginaries. Chapters explore how Black literature was being produced and circulated; how and why it marked its relation to other literary and expressive traditions; what geopolitical imaginaries it facilitated through representation; and what technologies, including print, enabled African Americans to pursue such a complex and ongoing aesthetic and political project. is a Professor in the English and Film Studies Department at the University of Alberta, where she teaches critical race theory, African American literature and theory, and historical Black feminisms. Her books include The Mulatta and the Politics of Race (); Press, Platform, Pulpit: Black Feminisms in the Era of Reform (); the six-volume edition African American Feminisms – in the Routledge History of Feminisms series (); and “We Must be Up and Doing”: A Reader in Early African American Feminisms (). She is a member of the UK-based international research network Black Female Intellectuals in the Historical and Contemporary Context, and is completing a book on early Black feminist use of media and its forms. -

'The Slaves' Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812'

H-War Hemmis on Smith, 'The Slaves' Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812' Review published on Tuesday, March 8, 2016 Gene Allen Smith. The Slaves' Gamble: Choosing Sides in the War of 1812. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. xiii + 257 pp. $27.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-230-34208-8. Reviewed by Timothy C. Hemmis (University of Southern Mississippi) Published on H-War (March, 2016) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey A Chance at Freedom In The Slaves’ Gamble, Gene Allen Smith tackles a seemingly simple question in early American history: “why did some free blacks and slaves side with the United States during the War of 1812, and why did others join the British, the Spanish, the Native American tribes, or maroon communities?” (p. xi). Smith discovers a complex and multifaceted answer. Tracing the service of many African American men from colonial times through the War of 1812, the author finds that moments of international conflict gave free and enslaved black men a chance at freedom if they chose wisely. Smith opens the book with the story of HMS Leopard stopping USS Chesapeake in 1807. He explains that three of the four sailors whom the British captured were black men claiming to be Americans. The Chesapeake-Leopard affair seemingly had little to do with race, but Smith argues that race was “central ... to the history of the subsequent War of 1812” (p. 2). War gave African American men an opportunity to choose their own futures; during several flash points in history, Smith demonstrates, free and enslaved blacks had a brief chance to determine their own destiny. -

Woodland Ferry History

Woodland Ferry: Crossing the Nanticoke River from the 1740s to the present Carolann Wicks Secretary, Department of Transportation Welcome! This short history of the Woodland Ferry, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was written to mark the commissioning of a new ferryboat, the Tina Fallon, in 2008. It is an interesting and colorful story. TIMELINE 1608 Captain John Smith explores 1843 Jacob Cannon Jr. murdered at the the Nanticoke River, and encounters wharf. Brother Isaac Cannon dies one Nanticoke Indians. Native Americans month later. Ferry passes to their sister have resided in the region for thousands Luraney Boling of years 1845 Inventory of Luraney Boling’s 1734 James Cannon purchases a estate includes “one wood scow, one land tract called Cannon’s Regulation at schooner, one large old scow, two small Woodland old scows, one ferry scow, one old and worn out chain cable, one lot of old cable 1743? James Cannon starts operating a chains and two scow chains, on and ferry about the wharves” 1748 A wharf is mentioned at the 1883 Delaware General Assembly ferry passes an act authorizing the Levy Court of Sussex County to establish and 1751 James Cannon dies and his son maintain a ferry at Woodland Jacob takes over the ferry 1885 William Ellis paid an annual 1766 A tax of 1,500 lbs. of tobacco salary of $119.99 by Sussex County for is paid “to Jacob Cannon for keeping operating the ferry a Ferry over Nanticoke River the Year past” 1930 Model “T” engine attached to the wooden ferryboat 1780 Jacob Cannon dies and -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1976, Volume 71, Issue No. 3

AKfLAND •AZIN Published Quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society FALL 1976 Vol. 71, No. 3 BOARD OF EDITORS JOSEPH L. ARNOLD, University of Maryland, Baltimore County JEAN BAKER, Goucher College GARY BROWNE, Wayne State University JOSEPH W. COX, Towson State College CURTIS CARROLL DAVIS, Baltimore RICHARD R. DUNCAN, Georgetown University RONALD HOFFMAN, University of Maryland, College Park H. H. WALKER LEWIS, Baltimore EDWARD C. PAPENFUSE, Hall of Records BENJAMIN QUARLES, Morgan State College JOHN B. BOLES, Editor, Towson State College NANCY G. BOLES, Assistant Editor RICHARD J. COX, Manuscripts MARY K. MEYER, Genealogy MARY KATHLEEN THOMSEN, Graphics FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE, 1906-1909 LOUIS H. DIELMAN, 1910-1937 JAMES W. FOSTER, 1938-1949, 1950-1951 HARRY AMMON, 1950 FRED SHELLEY, 1951-1955 FRANCIS C. HABER 1955-1958 RICHARD WALSH, 1958-1967 RICHARD R. DUNCAN, 1967-1974 P. WILLIAM FILBY, Director ROMAINE S. SOMERVILLE, Assistant Director The Maryland Historical Magazine is published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201. Contributions and correspondence relating to articles, book reviews, and any other editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor in care of the Society. All contributions should be submitted in duplicate, double-spaced, and consistent with the form out- lined in A Manual of Style (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969). The Maryland Historical Society disclaims responsibility for statements made by contributors. Composed and printed at Waverly Press, Inc., Baltimore, Maryland 21202,. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Maryland. © 1976, Maryland Historical Society. 6 0F ^ ^^^f^i"^^lARYLA/ i ^ RECORDS LIBRARY \9T6 00^ 26 HIST NAPOLIS, M^tl^ND Fall 1976 #. -

Chapter 1 - Introduction to the Corridor Management Plan

Introduction to the Corridor Management Plan, Statement 1 of Purpose, and Corridor Story CHAPTER 1 - INTRODUCTION TO THE CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN 1.1 - Statement of Purpose CMP began. Th ere has been an actively engaged group of corridor residents that began meeting in 2009 / 2010 Th e Nanticoke Heritage Byway (NHB) Corridor to discuss ways to enhance and promote the corridor’s Management Plan (CMP) is intended to provide a tremendous sites and resources. Th e current CMP detailed collection of information that will assist in process, which began offi cially in August 2013, has meeting the corridor Mission and Vision Statement also engaged a diverse group of vested stakeholders, (see Chapter 2.0) developed for the corridor. Th is including many of the original stakeholders. Th ese CMP will attempt to foster economic development, stakeholders include citizens, business owners, continued research, and set a clear course for future government and other public agencies, religious actions (projects) within the Nanticoke Heritage entities, and private entities. In an eff ort to include Byway region. In addition, the CMP will provide and coordinate with as many entities as possible the direction and foresight as to the proper course of following groups (which we call Stakeholder groups) promotion, use, and preservation of the corridor’s were coordinated with throughout the development resources. of the CMP. Th e CMP is a product of extensive coordination and 1.3.1 Steering Committee input from the NHB communities and stakeholders. Th e Steering Committee, which was formally Th is CMP is an extension of the people – the people of identifi ed in the early stages of this CMP the NHB. -

Underground Railroad Byway Delaware

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway Delaware Chapter 3.0 Intrinsic Resource Assessment The following Intrinsic Resource Assessment chapter outlines the intrinsic resources found along the corridor. The National Scenic Byway Program defines an intrinsic resource as the cultural, historical, archeological, recreational, natural or scenic qualities or values along a roadway that are necessary for designation as a Scenic Byway. Intrinsic resources are features considered significant, exceptional and distinctive by a community and are recognized and expressed by that community in its comprehensive plan to be of local, regional, statewide or national significance and worthy of preservation and management (60 FR 26759). Nationally significant resources are those that tend to draw travelers or visitors from regions throughout the United States. National Scenic Byway CMP Point #2 An assessment of the intrinsic qualities and their context (the areas surrounding the intrinsic resources). The Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Byway offers travelers a significant amount of Historical and Cultural resources; therefore, this CMP is focused mainly on these resource categories. The additional resource categories are not ignored in this CMP; they are however, not at the same level of significance or concentration along the corridor as the Historical and Cultural resources. The resources represented in the following chapter provide direct relationships to the corridor story and are therefore presented in this chapter. A map of the entire corridor with all of the intrinsic resources displayed can be found on Figure 6. Figures 7 through 10 provide detailed maps of the four (4) corridors segments, with the intrinsic resources highlighted. This Intrinsic Resource Assessment is organized in a manner that presents the Primary (or most significant resources) first, followed by the Secondary resources. -

Afua Cooper, "Ever True to the Cause of Freedom – Henry Bibb

Ever True to the Cause of Freedom Henry Bibb: Abolitionist and Black Freedom’s Champion, 1814-1854 Afua Cooper Black abolitionists in North America, through their activism, had a two-fold objective: end American slavery and eradicate racial prejudice, and in so doing promote race uplift and Black progress. To achieve their aims, they engaged in a host of pursuits that included lecturing, fund-raising, newspaper publishing, writing slave narratives, engaging in Underground Railroad activities, and convincing the uninitiated to do their part for the antislavery movement. A host of Black abolitionists, many of whom had substantial organizational experience in the United States, moved to Canada in the three decades stretching from 1830 to 1860. Among these were such activists as Henry Bibb, Mary Bibb, Martin Delany, Theodore Holly, Josiah Henson, Mary Ann Shadd, Samuel Ringgold Ward, J.C. Brown and Amelia Freeman. Some like Henry Bibb were escaped fugitive slaves, others like J.C. Brown had bought themselves out of slavery. Some like Amelia Freeman and Theodore Holly were free-born Blacks. None has had a more tragic past however than Henry Bibb. Yet he would come to be one of the 19th century’s foremost abolitionists. At the peak of his career, Bibb migrated to Canada and made what was perhaps his greatest contribution to the antislavery movement: the establishment of the Black press in Canada. This discussion will explore Bibb’s many contributions to the Black freedom movement but will provide a special focus on his work as a newspaper founder and publisher. Henry Bibb was born in slavery in Kentucky around 1814.1 Like so many other African American slaves, Bibb’s parentage was biracial. -

The Historic Woodland Ferry Continued from Pg 1 Isaac and His Younger Brother, Jacob Continued Until 1843

The Historic Woodland Ferry continued from pg 1 Isaac and his younger brother, Jacob continued until 1843. A sensational power the boat Jr. inherited the Cannon Ferry. The end came to their shady business along the cables. brothers were shrewd businessmen practices. On April 10, 1843, Jacob, The Delaware and became very wealthy. By 1816, Jr. was at the ferry dock, having Department of they owned almost 5000 acres of land, just returned from appealing to the Transportation operating not only the ferry, but stores, Governor for protection against began overseeing warehouses, and houses. They owned threats from people, whom he claimed the ferry in 1935, slaves and a number of commercial he had aided. He was approached purchasing a new vessels that traveled to Baltimore. by Owen O’Day, who accused Jacob wooden boat. By They became the loan sharks of the of stealing property, supposedly a 1958, the old ferry, day, lending money, extending credit, gum tree branch, containing a hive of known as the Patty Collection R. Zebley of Hagley Museum , F. Courtesy Ferry, Men at honey. In broad daylight, Cannon became unserviceable due to placed on the National Register Owen shot Jacob with his increased traffic and failure to meet of Historic Places, recognizing its musket. As Owen fled, U.S. Coast Guard standards. The state historical and cultural value. It is a part Jacob stumbled home. A seriously considered a bridge instead of the Nanticoke Heritage Byway. The doctor found over 27 pieces of refurbishing or replacing the ferry. Woodland Ferry keeps history alive at of musket shot in Jacob’s The cost of a bridge, plus the uproar this river crossing. -

William Cooper Nell. the Colored Patriots of the American Revolution

William Cooper Nell. The Colored Patriots of the American ... http://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/nell/nell.html About | Collections | Authors | Titles | Subjects | Geographic | K-12 | Facebook | Buy DocSouth Books The Colored Patriots of the American Revolution, With Sketches of Several Distinguished Colored Persons: To Which Is Added a Brief Survey of the Condition And Prospects of Colored Americans: Electronic Edition. Nell, William Cooper Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title. Text scanned (OCR) by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Images scanned by Fiona Mills and Sarah Reuning Text encoded by Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith First edition, 1999 ca. 800K Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1999. © This work is the property of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as long as this statement of availability is included in the text. Call number E 269 N3 N4 (Winston-Salem State University) The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South. All footnotes are moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs. Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references. All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively. All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively. -

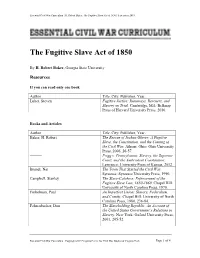

The Fugitive Slave Act Resources

Essential Civil War Curriculum | H. Robert Baker, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 | September 2015 The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 By H. Robert Baker, Georgia State University Resources If you can read only one book Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Lubet, Steven Fugitive Justice: Runaways, Rescuers, and Slavery on Trial. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2010. Books and Articles Author Title. City: Publisher, Year. Baker, H. Robert The Rescue of Joshua Glover: A Fugitive Slave, the Constitution, and the Coming of the Civil War. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006, 26-57. ———. Prigg v. Pennsylvania: Slavery, the Supreme Court, and the Ambivalent Constitution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2012. Brandt, Nat The Town That Started the Civil War. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1990. Campbell, Stanley The Slave-Catchers: Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, 1850-1860. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1970. Finkelman, Paul An Imperfect Union: Slavery, Federalism, and Comity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1980, 236-84. Fehrenbacher, Don The Slaveholding Republic: An Account of the United States Government’s Relations to Slavery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, 205-52. Essential Civil War Curriculum | Copyright 2015 Virginia Center for Civil War Studies at Virginia Tech Page 1 of 4 Essential Civil War Curriculum | H. Robert Baker, The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 | September 2015 Foner, Eric Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad. New York: W. W. Norton, 2015. Harrold, Stanley Border War: Fighting Over Slavery Before the Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010. -

To Make Their Own Way in the World the Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes

To Make Their Own Way in the World The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes Edited by Ilisa Barbash Molly Rogers DeborahCOPYRIGHT Willis © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD C LEGE To Make Their Own Way in the World The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes Edited by Ilisa Barbash Molly Rogers Deborah Willis With a foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. COPYRIGHT © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD C LEGE COPYRIGHT © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD C LEGE Contents 9 Foreword by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. 15 Preface by Jane Pickering 17 Introduction by Molly Rogers 25 Gallery: The Zealy Daguerreotypes Part I. Photographic Subjects Chapter 1 61 This Intricate Question The “American School” of Ethnology and the Zealy Daguerreotypes by Molly Rogers Chapter 2 71 The Life and Times of Alfred, Delia, Drana, Fassena, Jack, Jem, and Renty by Gregg Hecimovich Chapter 3 119 History in the Face of Slavery A Family Portrait by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham Chapter 4 151 Portraits of Endurance Enslaved People and Vernacular Photography in the Antebellum South by Matthew Fox-Amato COPYRIGHT © 2020 PRESIDENT AND FELLOWS OF HARVARD C LEGE Part II. Photographic Practice Chapter 5 169 The Curious Art and Science of the Daguerreotype by John Wood Chapter 6 187 Business as Usual? Scientific Operations in the Early Photographic Studio by Tanya Sheehan Chapter 7 205 Mr. Agassiz’s “Photographic Saloon” by Christoph Irmscher Part III. Ideas and Histories Chapter 8 235 Of Scientific Racists and Black Abolitionists The Forgotten Debate over Slavery and Race by Manisha Sinha Chapter 9 259 “Nowhere Else” South Carolina’s Role in a Continuing Tragedy by Harlan Greene Chapter 10 279 “Not Suitable for Public Notice” Agassiz’s Evidence by John Stauffer Chapter 11 297 The Insistent Reveal Louis Agassiz, Joseph T. -

1. Slavery, Resistance and the Slave Narrative

“I have often tried to write myself a pass” A Systemic-Functional Analysis of Discourse in Selected African American Slave Narratives Tobias Pischel de Ascensão Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Sprach- und Literaturwissenschaft der Universität Osnabrück Hauptberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Oliver Grannis Nebenberichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Ulrich Busse Osnabrück, 01.12.2003 Contents i Contents List of Tables iii List of Figures iv Conventions and abbreviations v Preface vi 0. Introduction: the slave narrative as an object of linguistic study 1 1. Slavery, resistance and the slave narrative 6 1.1 Slavery and resistance 6 1.2 The development of the slave narrative 12 1.2.1 The first phase 12 1.2.2 The second phase 15 1.2.3 The slave narrative after 1865 21 2. Discourse, power, and ideology in the slave narrative 23 2.1 The production of disciplinary knowledge 23 2.2 Truth, reality, and ideology 31 2.3 “The writer” and “the reader” of slave narratives 35 2.3.1 Slave narrative production: “the writer” 35 2.3.2 Slave narrative reception: “the reader” 39 3. The language of slave narratives as an object of study 42 3.1 Investigations in the language of the slave narrative 42 3.2 The “plain-style”-fallacy 45 3.3 Linguistic expression as functional choice 48 3.4 The construal of experience and identity 51 3.4.1 The ideational metafunction 52 3.4.2 The interpersonal metafunction 55 3.4.3 The textual metafunction 55 3.5 Applying systemic grammar 56 4.