From Mbube to Wimoweh: African Folk Music in Dual Systems of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Characteristics of Trauma

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Music and Trauma in the Contemporary South African Novel“ Verfasser Christian Stiftinger angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2011. Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 190 344 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: UF Englisch Betreuer: Univ. Prof. DDr . Ewald Mengel Declaration of Authenticity I hereby confirm that I have conceived and written this thesis without any outside help, all by myself in English. Any quotations, borrowed ideas or paraphrased passages have been clearly indicated within this work and acknowledged in the bibliographical references. There are no hand-written corrections from myself or others, the mark I received for it can not be deducted in any way through this paper. Vienna, November 2011 Christian Stiftinger Table of Contents 1. Introduction......................................................................................1 2. Trauma..............................................................................................3 2.1 The Characteristics of Trauma..............................................................3 2.1.1 Definition of Trauma I.................................................................3 2.1.2 Traumatic Event and Subjectivity................................................4 2.1.3 Definition of Trauma II................................................................5 2.1.4 Trauma and Dissociation............................................................7 2.1.5 Trauma and Memory...……………………………………………..8 2.1.6 Trauma -

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, and EMPIRE: a PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R

MAATSKAPPY, STATE, AND EMPIRE: A PRO-BOER REVISION Joseph R. Stromberg* As we approach the centennial of the Second Anglo–Boer War (Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, or “Second War for Freedom”), reassessment of the South African experience seems in order. Whether the recent surrender by Afrikaner political leaders of their “central theme” and the dismantling of their grandiose Apartheid state will lead to heaven on earth (as some of the Soweto “comrades” expected), or even to a merely tolerable multiracial polity, remains in doubt. Historians have tended to look for the origins of South Africa’s “very strange society” in the interaction of various peoples and political forces on a rapidly changing frontier, especially in the 19th century. APPROACHES TO SOUTH AFRICAN FRONTIER HISTORY At least two major schools of interpretation developed around these issues. The first, Cape Liberals, viewed the frontier Boers largely as rustic ruffians who abused the natives and disrupted or- derly economic progress only to be restrained, at last, by humani- tarian and legalistic British paternalists. Afrikaner excesses, therefore, were the proximate cause and justification of the Boer War and the consolidation of British power over a united South Africa. The “imperial factor” on this view was liberal and pro- gressive in intent if not in outcome. The opposing school were essentially Afrikaner nationalists who viewed the Boers as a uniquely religious people thrust into a dangerous environment where they necessarily resorted to force to overcome hostile African tribes and periodic British harassment. The two traditions largely agreed on the centrality of the frontier, but differed radically on the villains and heroes.1 Beginning in the 1960s and ’70s, a third position was heard, that of younger “South Africanists” driven to distraction (and some *Joseph R. -

Redalyc.Bona Spes

Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies E-ISSN: 2175-8026 [email protected] Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Brasil Gatti, José Bona Spes Ilha do Desterro: A Journal of English Language, Literatures in English and Cultural Studies, núm. 61, julio-diciembre, 2011, pp. 11-27 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Florianópolis, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=478348699001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative http//dx.doi.org/10.5007/2175-8026.2011n61p011 BONA Spes José Gatti Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná The main campus of the University of Cape Town is definitely striking, possibly one of the most beautiful in the world. It rests on the foot of the massive Devil’s Peak; not far from there lies the imposing Cape of Good Hope, a crossroads of two oceans. Accordingly, the university’s Latin motto is Bona Spes. With its neo- classic architecture, the university has the atmosphere of an enclave of British academic tradition in Africa. The first courses opened in 1874; since then, the UCT has produced five Nobel prizes and it forms, along with other well-established South African universities, one of the most productive research centers in the continent. I was sent there in 2009, in order to research on the history of South African audiovisual media, sponsored by Fapesp (Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo). -

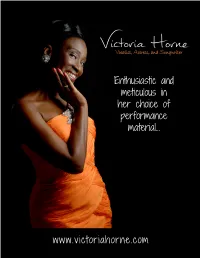

Enthusiastic and Meticulous in Her Choice of Performance Material

Enthusiastic and meticulous in her choice of performance material... www.victoriahorne.comwww.victoriahorne.com Victoria’s imaginative staging concepts are fresh, fascinating and specifically designed for each show and performance venue. Victoria’s appearance on stage is sensational, costumes are classy, exotic, and professional. Recordings One Day I’ll Fly Away Sound Of Your Body Time Free To Fly Videos Lady Of Soul Time After Time Victoria Horne & Friends Live www.victoriahorne.com Freshly Cooked On Tour with Andi and Alex Victoria appeared on the Andi and Alex Cooking Show singing Strange I’ve Seen That Face Before / Libertango in Vienna, Austria. Celebrity Jazz Vocalist Victoria Horne marks her debut visit to Thailand with an exclusive 3-month performance at Mandarin Oriental’s famous Bamboo Room Boogie Woogie - Festival de Boogie Laroquebrou I20 A unique Belgian performance coupled Victoria Horne with Blues / Boogie Woogie pianist RenaudPatigny & his Trio, for the Festival International de Boogie Woogie, Roquebrou Joe Turner’s Blues Bassist Live in Concert In Paris, Victoria joined Joe Turner’s Blues Bassist Live in Concert in France at the Quai Du Blues Club www.victoriahorne.com PROFESSIONAL TRAINING • Schools: The Black Studies Workshop at American Conservatory, San Francisco, Instructor Anna Beavers and Herbert Bergoff Studio, New York • Voice Instructors: Sue Seaton, Professor Boatner, Stewart Brady, Gina Maretta • Acting Instructors: Shannelle Perry, Louise Stubbs • Dance Instructors: Phil Black, Eleanor Harris, Pepsi Bethel • Voice Instructors: Sue Seaton, Professor Boatner, Stewart Brady, Gina Maretta • Acting Instructors: Shannelle Perry, Louise Stubbs • Dance Instructors: Phil Black, Eleanor Harris, Pepsi Bethel RECORDINGS FROM 2006-2017 • Christmas in St. -

1. Matome Ratiba

JICLT Journal of International Commercial Law and Technology Vol. 7, Issue 1 (2012) “The sleeping lion needed protection” – lessons from the Mbube ∗∗∗ (Lion King) debacle Matome Melford Ratiba Senior Lecturer, College of Law University of South Africa (UNISA) [email protected] Abstract : In 1939 a young musician from the Zulu cultural group in South Africa, penned down what came to be the most popular albeit controversial and internationally acclaimed song of the times. Popular because the song somehow found its way into international households via the renowned Disney‘s Lion King. Controversial because the popularity passage of the song was tainted with illicit and grossly unfair dealings tantamount to theft and dishonest misappropriation of traditional intellectual property, giving rise to a lawsuit that ultimately culminated in the out of court settlement of the case. The lessons to be gained by the world and emanating from this dramatics, all pointed out to the dire need for a reconsideration of measures to be urgently put in place for the safeguarding of cultural intellectual relic such as music and dance. 1. Introduction Music has been and, and continues to be, important to all people around the world. Music is part of a group's cultural identity; it reflects their past and separates them from surrounding people. Music is rooted in the culture of a society in the same ways that food, dress and language are”. Looked at from this perspective, music therefore constitute an integral part of cultural property that inarguably requires concerted and decisive efforts towards preservation and protection of same from unjust exploitation and prevalent illicit transfer of same. -

Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: the Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa

VOL. 42, NO. 1 ETHNOMUSICOLOGY WINTER 1998 Mirror, Mediator, and Prophet: The Music Indaba of Late-Apartheid South Africa INGRID BIANCA BYERLY DUKE UNIVERSITY his article explores a movement of creative initiative, from 1960 to T 1990, that greatly influenced the course of history in South Africa.1 It is a movement which holds a deep affiliation for me, not merely through an extended submersion and profound interest in it, but also because of the co-incidence of its timing with my life in South Africa. On the fateful day of the bloody Sharpeville march on 21 March 1960, I was celebrating my first birthday in a peaceful coastal town in the Cape Province. Three decades later, on the weekend of Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in February 1990, I was preparing to leave for the United States to further my studies in the social theories that lay at the base of the remarkable musical movement that had long engaged me. This musical phenomenon therefore spans exactly the three decades of my early life in South Africa. I feel privi- leged to have experienced its development—not only through growing up in the center of this musical moment, but particularly through a deepen- ing interest, and consequently, an active participation in its peak during the mid-1980s. I call this movement the Music Indaba, for it involved all sec- tors of the complex South African society, and provided a leading site within which the dilemmas of the late-apartheid era could be explored and re- solved, particularly issues concerning identity, communication and social change. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

Pete Seeger and Intellectual Property Law

Teaching The Hudson River Valley Review Teaching About “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” –Steve Garabedian Lesson Plan Introduction: Students will use the Hudson River Valley Review (HRVR) Article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” as a model for an exemplary research paper (PDF of the full article is included in this PDF). Lesson activities will scaffold student’s understanding of the article’s theme as well as the article’s construction. This lesson concludes with an individual research paper constructed by the students using the information and resources understood in this lesson sequence. Each activity below can be adapted according to the student’s needs and abilities. Suggested Grade Level: 11th grade US History: Regents level and AP level, 12th grade Participation in Government: Regents level and AP level. Objective: Students will be able to: Read and comprehend the provided text. Analyze primary documents, literary style. Explain and describe the theme of the article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” in a comprehensive summary. After completing these activities students will be able to recognize effective writing styles. Standards Addressed: Students will: Use important ideas, social and cultural values, beliefs, and traditions from New York State and United States history illustrate the connections and interactions of people and events across time and from a variety of perspectives. Develop and test hypotheses about important events, eras, or issues in United States history, setting clear and valid criteria for judging the importance and significance of these events, eras, or issues. -

Identity, Nationalism, and Resistance in African Popular Music

Instructor: Jeffrey Callen, Ph.D., Adjunct Faculty, Department of Performing Arts, University of San Francisco SYLLABUS ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 98T: IDENTITY, NATIONALISM AND RESISTANCE IN AFRICAN POPULAR MUSIC How are significant cultural changes reflected in popular music? How does popular music express the aspirations of musicians and fans? Can popular music help you create a different sense of who you are? Course Statement: The goal of this course is to encourage you to think critically about popular music. Our focus will be on how popular music in Africa expresses people’s hopes and aspirations, and sense of who they are. Through six case studies, we will examine the role popular music plays in the formation of national and transnational identities in Africa, and in mobilizing cultural and political resistance. We will look at a wide variety of African musical styles from Congolese rumba of the 1950s to hip-hop in a variety of African countries today. Readings: There is one required book for this course: Music is the Weapon of the Future by Frank Tenaille. Additional readings are posted on the Blackboard site for this class. Readings are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed Listenings: Listenings (posted on Blackboard) are to be done prior to the week in which they are discussed. If entire albums are assigned for listening, listen to as much as you have time for. The Course Blog: The course blog will be an important part of this course. On it you will post your reactions to the class listenings and readings. It also lists internet resources that will prove helpful in finding supplemental information on class subjects and in preparing your final research project. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

Looking in New Ways at Frontiers for Literary Journalism

194 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 11, No. 2, December 2019 Looking in New Ways at Frontiers for Literary Journalism At the Faultline: Writing White in South African Literary Journalism by Claire Scott. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2018. Paperback, 208 pp., USD$27. Reviewed by Lesley Cowling, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa he study of nonfiction writing in its variety of Tforms has not had an established disciplinary home in South Africa and, indeed, the very definition of what is being studied, where, is still open to discussion. As other writers in this journal have noted repeatedly over the last decade, English literature departments in many countries have studied fiction, poetry, and theater, with nonfiction rarely given the nod. This has been true of South African universities too, where, as Leon de Kock wrote in South Africa in the Global Imaginary in 2004, literature departments until the late 1970s had been “smugly Anglophile and dismissive of the ‘local’ ” (6). Journalism programs, a potential disciplinary home for literary journalism, have tended to focus on preparing students for work in the media sector. With South Africa having so few platforms for literary and longform journalism, little attention has been given to these forms beyond feature writing and magazine courses. Nonfiction writing must necessarily find its way into the academy through other disciplines. It has done so through African literature, history, library sciences, and the more recently emerging creative writing programs. It is also being ushered into local scholarship via the particular research interests of individual scholars. Thus, although South Africa historically has had a rich set of writers of literary nonfiction, some of whom have been internationally recognized, their study is fragmented over academic disciplines. -

'Women of Mbube: We Are Peace, We Are Strength'

Music News Release: for immediate use ‘Women of Mbube: We are peace, we are strength’ - New Album from Nobuntu “… joy seems central to Nobuntu's existence: it's present in their glorious singing, their expressive dancing, even in their dress - plaids, stripes, florals in colours as exuberant as their vocals.” cltampa.com Album: Obabes beMbube (‘Women of Mbube’) Artists: Nobuntu Genre: African Mbube Speciality: Female a cappella group Language: Ndebele Label: 10th District Music/Zimbabwe Release: 24 November, 2018 It takes courage, persistence and a great deal of talent to create new songs in a genre of already impeccable standards. Zimbabwean five-piece, Nobuntu are blessed with all three. ‘Obabes beMbube’ is Nobuntu’s new 13-song album of mbube music sung in Ndebele celebrating life, nature, divine inspiration and the power of music as a healing force. Five strong female voices beautifully blended singing a cappella harmonies. ‘Obabes beMbube’ builds on the success of ‘Thina’ and ‘Ekhaya’ which were released in 2013 and 2015 respectively. The music represents a bold shift from the previous bodies of work which featured a fusion of afro jazz, a cappella, gospel and traditional folk tracks. The album name ‘Obabes beMbube’ is Ndebele for ‘women of mbube’, an assertion of Nobuntu’s position as a musical force in a genre that is traditionally a male domain. Mbube (Zulu for ‘lion’, pronounced ‘eem-boo-bay’) was released as the song (‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’) ‘Mbube’ written by Solomon Linda in Johannesburg and released through Gallo Record Company in 1939. ‘Mbube’ became a UK and USA #1 hit single in 1969 by the Tokens – and is now the name widely used for the South African a cappella genre, mbube.