1. Matome Ratiba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enthusiastic and Meticulous in Her Choice of Performance Material

Enthusiastic and meticulous in her choice of performance material... www.victoriahorne.comwww.victoriahorne.com Victoria’s imaginative staging concepts are fresh, fascinating and specifically designed for each show and performance venue. Victoria’s appearance on stage is sensational, costumes are classy, exotic, and professional. Recordings One Day I’ll Fly Away Sound Of Your Body Time Free To Fly Videos Lady Of Soul Time After Time Victoria Horne & Friends Live www.victoriahorne.com Freshly Cooked On Tour with Andi and Alex Victoria appeared on the Andi and Alex Cooking Show singing Strange I’ve Seen That Face Before / Libertango in Vienna, Austria. Celebrity Jazz Vocalist Victoria Horne marks her debut visit to Thailand with an exclusive 3-month performance at Mandarin Oriental’s famous Bamboo Room Boogie Woogie - Festival de Boogie Laroquebrou I20 A unique Belgian performance coupled Victoria Horne with Blues / Boogie Woogie pianist RenaudPatigny & his Trio, for the Festival International de Boogie Woogie, Roquebrou Joe Turner’s Blues Bassist Live in Concert In Paris, Victoria joined Joe Turner’s Blues Bassist Live in Concert in France at the Quai Du Blues Club www.victoriahorne.com PROFESSIONAL TRAINING • Schools: The Black Studies Workshop at American Conservatory, San Francisco, Instructor Anna Beavers and Herbert Bergoff Studio, New York • Voice Instructors: Sue Seaton, Professor Boatner, Stewart Brady, Gina Maretta • Acting Instructors: Shannelle Perry, Louise Stubbs • Dance Instructors: Phil Black, Eleanor Harris, Pepsi Bethel • Voice Instructors: Sue Seaton, Professor Boatner, Stewart Brady, Gina Maretta • Acting Instructors: Shannelle Perry, Louise Stubbs • Dance Instructors: Phil Black, Eleanor Harris, Pepsi Bethel RECORDINGS FROM 2006-2017 • Christmas in St. -

Form L5: Title Registration/08

NICO CARSTENS AS INNOVEERDER VAN SUID-AFRIKAANSE POPULÊRE MUSIEK Susanna Helena Robina Louw Voorgelê om te voldoen aan die vereistes vir die graad MAGISTER MUSICAE in die Fakulteit Geesteswetenskappe, Departement Musiek, aan die Universiteit van die Vrystaat Studieleier: Prof. N.G.J. Viljoen Medestudieleier: Prof. M. Viljoen Januarie 2013 VERKLARING Ek verklaar hiermee dat die verhandeling wat hierby vir die graadMagister Musicae aan die Universiteit van die Vrystaat deur myingedien word, my selfstandige werk is en nie voorheen deurmy vir ’n graad aan ’n ander universiteit/fakulteit ingedien isnie. Ek doen voorts afstand van die outeursreg op dieverhandeling ten gunste van die Universiteit van die Vrystaat. ____________________________________ i ERKENNINGS By die voltooiing van hierdie verhandeling is dit die behoefte van my hart om persone en instansies wat my op een of ander wyse met genoemde materiaal behulpsaam was, opreg te bedank: My studieleier, prof Nicol Viljoen, en mede-studieleier, prof. Martina Viljoen, vir hulle besondere kundige leiding in alle fases en fasette van hierdie navorsing. SAMRO, vir die beskikbaarstelling van navorsingmateriaal, maar veral aan dié personeel wat genoemde materiaal so goedgunstiglik behulpsaam was. SABC en hulle Argief vir klank- en beeldmateriaal. Die FAK/SAMRO/National Arts Council of South Africa, vir finansiële bystand om hierdie projek te voltooi. Ingrid Howard, wat as behulpsame tussenganger opgetree het in my kontak en ontmoetings met Nico Carstens. Corrie Geldenhuys, vir die taalkundige versorging van die teks. Nico, die inligting hierin vervat, is net ’n fraksie van alles wat ek van jou ontvang het. Geen akademiese geskrif kan in elk geval vriendelikheid, openhartigheid en gasvryheid omskryf nie. -

Pete Seeger and Intellectual Property Law

Teaching The Hudson River Valley Review Teaching About “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” –Steve Garabedian Lesson Plan Introduction: Students will use the Hudson River Valley Review (HRVR) Article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” as a model for an exemplary research paper (PDF of the full article is included in this PDF). Lesson activities will scaffold student’s understanding of the article’s theme as well as the article’s construction. This lesson concludes with an individual research paper constructed by the students using the information and resources understood in this lesson sequence. Each activity below can be adapted according to the student’s needs and abilities. Suggested Grade Level: 11th grade US History: Regents level and AP level, 12th grade Participation in Government: Regents level and AP level. Objective: Students will be able to: Read and comprehend the provided text. Analyze primary documents, literary style. Explain and describe the theme of the article: “Teaspoon Brigade: Pete Seeger, Folk Music, and International Property Law” in a comprehensive summary. After completing these activities students will be able to recognize effective writing styles. Standards Addressed: Students will: Use important ideas, social and cultural values, beliefs, and traditions from New York State and United States history illustrate the connections and interactions of people and events across time and from a variety of perspectives. Develop and test hypotheses about important events, eras, or issues in United States history, setting clear and valid criteria for judging the importance and significance of these events, eras, or issues. -

Mahlathini Melodi Yalla Mp3, Flac, Wma

Mahlathini Melodi Yalla mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Melodi Yalla Country: South Africa Released: 2007 Style: African MP3 version RAR size: 1904 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1363 mb WMA version RAR size: 1235 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 389 Other Formats: DXD MPC DMF AAC MP2 TTA DTS Tracklist 1 Gazette 2 Melodi Yalla 3 Thuntswane Basadi 4 Thuto Kelefa 5 Bonang Suna 6 Reya Dumedisa 7 Mme Ngwana Walla 8 Jive Makgona Companies, etc. Marketed By – Gallo Record Company Distributed By – Gallo Record Company Record Company – Gallo-GRC Record Co. (Pty) Ltd. Recorded At – RPM Studios Copyright (c) – Gallo Record Company Published By – Gallo Music Publishers Credits Songwriter – Mahlathini And The Mahotella Queens Notes Reissue in Digital from a 1988 LP Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 6 001212 266134 Matrix / Runout: IFPI L142 WWW.CDT.CO.ZA CDBL617-1 Mastering SID Code: IFPI L142 Mould SID Code: IFPI 2727 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Mahlathini*, Mahotella Mahlathini*, Queens and the Gallo-GRC Mahotella Queens South BL 617 Makgona Tsotle Band* - Record Co. BL 617 1988 and the Makgona Africa Melodi Yalla (LP, (Pty) Ltd. Tsotle Band* Album) Related Music albums to Melodi Yalla by Mahlathini Mahlathini And The Mahotella Queens - Thokozile Mahlathini & Mahotella Queens - Umuntu Mfaz' Omnyama - Khula Tshitshi Lami The Art Of Noise Featuring Mahlathini And The Mahotella Queens - Yebo! Ladysmith Black Mambazo - Favourites Mahotella Queens - Izibani Zomgqashiyo Johannes Kerkorrel - Tien Jaar Later El Gallo Rojo - El dìa de los muertos Mahlathini Nezintombi Zomgqashiyo - Pheletsong Ya Lerato Patricia Majalisa - Poverty. -

Table of Contents

1 •••I I Table of Contents Freebies! 3 Rock 55 New Spring Titles 3 R&B it Rap * Dance 59 Women's Spirituality * New Age 12 Gospel 60 Recovery 24 Blues 61 Women's Music *• Feminist Music 25 Jazz 62 Comedy 37 Classical 63 Ladyslipper Top 40 37 Spoken 65 African 38 Babyslipper Catalog 66 Arabic * Middle Eastern 39 "Mehn's Music' 70 Asian 39 Videos 72 Celtic * British Isles 40 Kids'Videos 76 European 43 Songbooks, Posters 77 Latin American _ 43 Jewelry, Books 78 Native American 44 Cards, T-Shirts 80 Jewish 46 Ordering Information 84 Reggae 47 Donor Discount Club 84 Country 48 Order Blank 85 Folk * Traditional 49 Artist Index 86 Art exhibit at Horace Williams House spurs bride to change reception plans By Jennifer Brett FROM OUR "CONTROVERSIAL- SUffWriter COVER ARTIST, When Julie Wyne became engaged, she and her fiance planned to hold (heir SUDIE RAKUSIN wedding reception at the historic Horace Williams House on Rosemary Street. The Sabbats Series Notecards sOk But a controversial art exhibit dis A spectacular set of 8 color notecards^^ played in the house prompted Wyne to reproductions of original oil paintings by Sudie change her plans and move the Feb. IS Rakusin. Each personifies one Sabbat and holds the reception to the Siena Hotel. symbols, phase of the moon, the feeling of the season, The exhibit, by Hillsborough artist what is growing and being harvested...against a Sudie Rakusin, includes paintings of background color of the corresponding chakra. The 8 scantily clad and bare-breasted women. Sabbats are Winter Solstice, Candelmas, Spring "I have no problem with the gallery Equinox, Beltane/May Eve, Summer Solstice, showing the paintings," Wyne told The Lammas, Autumn Equinox, and Hallomas. -

'Women of Mbube: We Are Peace, We Are Strength'

Music News Release: for immediate use ‘Women of Mbube: We are peace, we are strength’ - New Album from Nobuntu “… joy seems central to Nobuntu's existence: it's present in their glorious singing, their expressive dancing, even in their dress - plaids, stripes, florals in colours as exuberant as their vocals.” cltampa.com Album: Obabes beMbube (‘Women of Mbube’) Artists: Nobuntu Genre: African Mbube Speciality: Female a cappella group Language: Ndebele Label: 10th District Music/Zimbabwe Release: 24 November, 2018 It takes courage, persistence and a great deal of talent to create new songs in a genre of already impeccable standards. Zimbabwean five-piece, Nobuntu are blessed with all three. ‘Obabes beMbube’ is Nobuntu’s new 13-song album of mbube music sung in Ndebele celebrating life, nature, divine inspiration and the power of music as a healing force. Five strong female voices beautifully blended singing a cappella harmonies. ‘Obabes beMbube’ builds on the success of ‘Thina’ and ‘Ekhaya’ which were released in 2013 and 2015 respectively. The music represents a bold shift from the previous bodies of work which featured a fusion of afro jazz, a cappella, gospel and traditional folk tracks. The album name ‘Obabes beMbube’ is Ndebele for ‘women of mbube’, an assertion of Nobuntu’s position as a musical force in a genre that is traditionally a male domain. Mbube (Zulu for ‘lion’, pronounced ‘eem-boo-bay’) was released as the song (‘The Lion Sleeps Tonight’) ‘Mbube’ written by Solomon Linda in Johannesburg and released through Gallo Record Company in 1939. ‘Mbube’ became a UK and USA #1 hit single in 1969 by the Tokens – and is now the name widely used for the South African a cappella genre, mbube. -

HISTORY WORKSHOP University Ol the Witwatersrand 1 Jan Smuts Avenue Johannesburg 2001

r\- y /"> UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND HISTORY WORKSHOP University ol the Witwatersrand 1 Jan Smuts Avenue Johannesburg 2001 THE MAKING OF CLASS 9-14 February, 1987 AUTHOR: V. Erlmann TITLE: "Singing Brings Joy To The Distressed" The Social History Of Zulu Migrant Workers' Choral Comnetions 1. INTRODUCTION The crucial role played by the system of cheap migrant labor as the backbone of South African capitalism is reflected in an extensive literature. However, this rich academic output con- trasts with a remarkable paucity of studies on migrant workers' consciousness and forms of cultural expression. Among the reasons for this neglect not the least important is the impact of the South African system of labor migration itself on the minds of scholars. Until at least the 1950s, the prevailing paradigm in African labor studies has been detribalization (Freund 1984:3) Since labor migration - so the argument went - undermined tradi- tional cultural values and created a cultural vacuum in the bur- geoning towns and industrial centers of the subcontinent, neither the collapsed cultural formations of the rural hinterland nor the urban void seemed to merit closer attention. The late 1950s some- what altered the picture, as scholars increasingly focused on what after all appeared to be new cultural formations in the cities: the dance clubs, churches, credit associations and early trade unions (Ranger 1975, Mitchell 1956). This literature em- phasized the ways in which the urban population attempted to com- pensate for the loss of the rural socio-economic order in "retribalizing", restructuring the urban forms of social interac- tion along tribal lines. -

Great Instrumental

I grew up during the heyday of pop instrumental music in the 1950s and the 1960s (there were 30 instrumental hits in the Top 40 in 1961), and I would listen to the radio faithfully for the 30 seconds before the hourly news when they would play instrumentals (however the first 45’s I bought were vocals: Bimbo by Jim Reeves in 1954, The Ballad of Davy Crockett with the flip side Farewell by Fess Parker in 1955, and Sixteen Tons by Tennessee Ernie Ford in 1956). I also listened to my Dad’s 78s, and my favorite song of those was Raymond Scott’s Powerhouse from 1937 (which was often heard in Warner Bros. cartoons). and to records that my friends had, and that their parents had - artists such as: (This is not meant to be a complete or definitive list of the music of these artists, or a definitive list of instrumental artists – rather it is just a list of many of the instrumental songs I heard and loved when I was growing up - therefore this list just goes up to the early 1970s): Floyd Cramer (Last Date and On the Rebound and Let’s Go and Hot Pepper and Flip Flop & Bob and The First Hurt and Fancy Pants and Shrum and All Keyed Up and San Antonio Rose and [These Are] The Young Years and What’d I Say and Java and How High the Moon), The Ventures (Walk Don't Run and Walk Don’t Run ‘64 and Perfidia and Ram-Bunk-Shush and Diamond Head and The Cruel Sea and Hawaii Five-O and Oh Pretty Woman and Go and Pedal Pusher and Tall Cool One and Slaughter on Tenth Avenue), Booker T. -

Sing Along Boulder Sing Along

SINGSING ALONGALONG WORLD BOULDERBOULDER SINGING DAY The singalong for everyone Saturday, Oct. 22, 2016, 11:30 am – 1:30 pm Boulder Courthouse lawn at Pearl Street October 22, 2016 The singing event for everyone www.WorldSingingDay.org Presented by World Singing Day and the United Nations Association of Boulder County Led by Face, with the Rocky Mountain Chorale, Songbirds Girl Scout Choir, UNC’s Vocal Iron a cappella group, and Up with People alumni World Singing Day Founded in 2012 by Boulder musician Scott Johnson, World Singing Day brings people together in their communities all around the world through the simple act of singing together. It’s an opportunity each year to celebrate our global family through the international language of music. Our goal for 2016 is to have community singalongs on all seven continents and reach over one million people through videos and social media. A 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, World Singing Day is not religious or political, nor does it promote any one country or culture. It aims to transcend those differences and celebrate what we all share as human beings. WorldSingingDay.org United Nations Association of Boulder County The UNA is dedicated to educating, inspiring and mobilizing people to support the principles and vital work of the United Nations in its efforts to promote peace around the world. Come celebrate UN Day on Monday, October 24. UNAboulder.org Dear Boulder, Thank you for taking part in the 2nd Annual Sing Along Boulder. It’s my vision that communities around the world will gather like this on the same day each year to sing together, have fun, and celebrate our common humanity. -

Vol. 9 Band Music New Publications Wormerveer, the Netherlands

Molenaar Edition Vol. 9 Band Music new publications Wormerveer, the Netherlands Published by Distributed by Molenaar Edition www.molenaar.com Industrieweg 23 NL 1521 ND Wormerveer the Netherlands Tel: +31 (0)75 - 628 68 59 Fax: +31 (0)75 - 621 49 91 E m a i l : o c e @ m o l e n a a r. c o m We b s i t e : w w w. m o l e n a a r. c o m Molenaar Edition New Publications for Band Colofon Molenaar Edition BV Industrieweg 23 NL 1521 ND Wormerveer the Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)75 - 628 68 59 Fax: +31 (0)75 - 621 49 91 Email: [email protected] Website: www.molenaar.com Please note that our P.O. Box is not available anymore © 2009 Molenaar Edition BV - Wormerveer - the Netherlands Copying of sheetmusic from this catalogue is illegal. Kopiëren van bladmuziek uit deze catalogus is verboden. Das Kopieren der Blattmusik aus diesem Katalog ist verboten Index Genre Track Title Instrumentation Page Arrangement Light 01 Bill Conti’s Famous TV Themes Co/Fa 4 02 German Charts Co/Fa 4 0 MacArthur Park Co/Fa 5 04 Beyond the Sea Co/Fa 5 05 Mr. Bojangles Co/Fa 6 06 Something Groovy Co/Fa 6 07-09 Three Brass Cats Co/Fa 7 10 Cats Co 7 11 Mary Poppins Co/Fa 9 Original Light 12 A New Boogie Woogie Co/Fa 9 Solo and Band 1 Against All Odds Co/Fa 11 14 Ave Maria Co/Fa 11 15 Concertino for Tuba Co/Fa/Br 11 Original 16-18 Manhattan Symphony Co 1 19-20 Jad-A-Daj Co 1 21-22 Dis-Tensions-dis Co 15 2-26 Suite Arogno Co 15 27 Draco Co 15 28-0 Galactic Suite Co 16 1-2 Reclamation Co/Fa/Br 16 Flexible Wind -6 Astro Suite Co/Fa 17 7-9 Three Unsquare Dances Co/Fa/Br 17 -

From Mbube to Wimoweh: African Folk Music in Dual Systems of Law

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Fordham University School of Law Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 20 Volume XX Number 1 Volume XX Book 1 Article 5 2009 From Mbube to Wimoweh: African Folk Music in Dual Systems of Law Deborah Wassel Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Deborah Wassel, From Mbube to Wimoweh: African Folk Music in Dual Systems of Law, 20 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 289 (2009). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol20/iss1/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Mbube to Wimoweh: African Folk Music in Dual Systems of Law Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank the incredible editors and staff of the IPLJ for their hard work, as well as Professor Tracy Higgins, without whose expertise this Note would not be possible. A special thanks to my parents and sister, whose endless love and support gave me the strength and drive to finish. Finally, I am grateful to Dan for everything—I couldn’t have done any of this without you. -

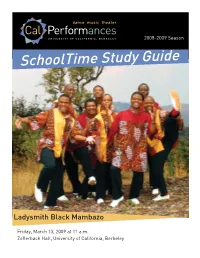

Ladysmith Black Mambazo Study Guide 0809.Indd

2008-2009 Season SchoolTime Study Guide Ladysmith Black Mambazo Friday, March 13, 2009 at 11 a.m. Zellerbach Hall, University of California, Berkeley Welcome to SchoolTime! On Friday, March 13, 2009, at 11 am, your class will attend a performance of South Africa’s most renowned vocal group, Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Founded in the early 1960s by South African visionary singer and activist Joseph Shabalala, Ladysmith Black Mambazo is considered a national treasure in their native country. The group has revolutionized traditional South African choral-group singing with their distinctive version of isicathamiya (Is-cot-a-MEE-ya), which comes from the powerfully uplifting songs of Zulu mine workers popularized during the apartheid era. Using This Study Guide This study guide will help engage your students with the performance and enrich their fi eld trip to Zellerbach Hall. Before coming to the performance, we encourage you to: • Copy the student resource sheet on page 2 & 3 and hand it out to your students several days before the show. • Discuss the information on pages 4- 5 about the performance and the artists with your students. • Read to your students from the About the Art Form on page 6 and About South Africa sections on page 8. • Engage your students in two or more of the activities on pages 11-12. • Refl ect with your students by asking them guiding questions, which you can fi nd on pages 2, 4, 6 & 8. • Immerse students further into the art form by using the glossary and resource sections on pages 12-13. At the performance: Your students