Cumberland County History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

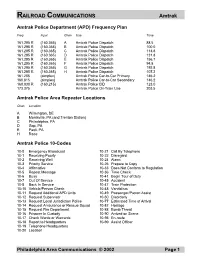

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 71.9 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department 10-88 Bomb Threat 10-16 -

Freight Rail B

FREIGHT RAIL B Pennsylvania has 57 freight railroads covering 5127 miles across the state, ranking it 4th largest rail network by mileage in the U.S. By 2035, 246 million tons of freight is expected to pass through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, an increase of 22 percent over 2007 levels. Pennsylvania’s railroad freight demand continues to exceed current infrastructure. Railroad traffic is steadily returning to near- World War II levels, before highways were built to facilitate widespread movement of goods by truck. Rail projects that could be undertaken to address the Commonwealth’s infrastructure needs total more than $280 million. Annual state-of-good-repair track and bridge expenditures for all railroad classes within the Commonwealth are projected to be approximately $560 million. Class I railroads which are the largest railroad companies are poised to cover their own financial needs, while smaller railroads are not affluent enough and some need assistance to continue service to rural areas of the state. BACKGROUND A number of benefits result from using rail freight to move goods throughout the U.S. particularly on longer routes: congestion mitigation, air quality improvement, enhancement of transportation safety, reduction of truck traffic on highways, and economic development. Railroads also remain the safest and most cost efficient mode for transporting hazardous materials, coal, industrial raw materials, and large quantities of goods. Since the mid-1800s, rail transportation has been the centerpiece of industrial production and energy movement. Specifically, in light of the events of September 11, 2001 and from a national security point of view, railroads are one of the best ways to produce a more secure system for transportation of dangerous or hazardous products. -

RAIL (FREIGHT) B 2006 Report Card for Pennsylvania’S Infrastructure

RAIL (FREIGHT) B 2006 Report Card for Pennsylvania’s Infrastructure In 1998, 919 million tons of freight passed through the Commonwealth. In 2020, that value is expected to be 1,397 million tons. Railroad freight demand is growing at a much faster rate than the general population, and railroad traffic is steadily approaching World War II levels. Projects that could be undertaken to address the Commonwealth’s infrastructure needs total some $280 million. Annual state of good repair track and bridge expenditures for all railroad classes within the state are projected to be approximately $560 million. Class I and larger railroads are more poised to cover their own financial needs. Smaller railroads are not as fortunate and need the most assistance to remain competitive. BACKGROUND A number of benefits result from supporting rail freight: congestion mitigation, air quality improvement, improving transportation safety, curtailing truck traffic growth on highways, job growth and economic development. Railroads also remain the safest and most viable mode for transporting hazardous materials, coal, industrial raw materials and large quantities of goods. Since the mid-1800’s, rail transportation has been the centerpiece of industrial production and energy generation. Specifically, in light of September 11th and from a national security point of view, railroads are one of most secure options for transporting dangerous or hazardous products. In fact, the majority of spent nuclear fuel rods will likely be sent via rail to the newly established federal depository. Surely, many of these shipments will pass through the Keystone State. By further improving the rail infrastructure, railroad operation can become even safer and more difficult to disrupt by any terrorist group. -

Amtrak Northeast Corridor Agreement

RECEIPT OF AGREEMENT This is to certify that I have received the Amtrak/Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees (NEC) Agreement, effective May 19, 1976, updated March 1, 1999. _____________________________ (Employee Signature) _____________________________ (Date) _____________________________ (Occupation) _____________________________ (Location) AGREEMENT Entered Into By and Between THE NATIONAL RAILROAD PASSENGER CORPORATION (AMTRAK) NORTHEAST CORRIDOR And Its Employees Represented By THE BROTHERHOOD OF MAINTENANCE OF WAY EMPLOYEES Note: It is understood that this reprinting is a synthesis in one document of the provisions of the current labor agreement. This is intended as a guide. It is not a separate agreement between the parties. If any dispute arises as to the proper interpretation or application of any rules, the terms of the actual negotiated labor agreement shall govern. (Synthesis printed April, 1999) BMWE-NEC INDEX SCOPE AND WORK CLASSIFICATIONS.................................................................................11 Scope...................................................................................................................................... 11 Exception................................................................................................................................. 12 Work Classification Rule ........................................................................................................... 20 Bridge And Building And Track Departments ........................................................................... -

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak

RAILROAD COMMUNICATIONS Amtrak Amtrak Police Department (APD) Frequency Plan Freq Input Chan Use Tone 161.295 R (160.365) A Amtrak Police Dispatch 88.5 161.295 R (160.365) B Amtrak Police Dispatch 100.0 161.295 R (160.365) C Amtrak Police Dispatch 114.8 161.295 R (160.365) D Amtrak Police Dispatch 131.8 161.295 R (160.365) E Amtrak Police Dispatch 156.7 161.295 R (160.365) F Amtrak Police Dispatch 94.8 161.295 R (160.365) G Amtrak Police Dispatch 192.8 161.295 R (160.365) H Amtrak Police Dispatch 107.2 161.205 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Primary 146.2 160.815 (simplex) Amtrak Police Car-to-Car Secondary 146.2 160.830 R (160.215) Amtrak Police CID 123.0 173.375 Amtrak Police On-Train Use 203.5 Amtrak Police Area Repeater Locations Chan Location A Wilmington, DE B Morrisville, PA (and Trenton Station) C Philadelphia, PA D Gap, PA E Paoli, PA H Race Amtrak Police 10-Codes 10-0 Emergency Broadcast 10-21 Call By Telephone 10-1 Receiving Poorly 10-22 Disregard 10-2 Receiving Well 10-24 Alarm 10-3 Priority Service 10-26 Prepare to Copy 10-4 Affirmative 10-33 Does Not Conform to Regulation 10-5 Repeat Message 10-36 Time Check 10-6 Busy 10-41 Begin Tour of Duty 10-7 Out Of Service 10-45 Accident 10-8 Back In Service 10-47 Train Protection 10-10 Vehicle/Person Check 10-48 Vandalism 10-11 Request Additional APD Units 10-49 Passenger/Patron Assist 10-12 Request Supervisor 10-50 Disorderly 10-13 Request Local Jurisdiction Police 10-77 Estimated Time of Arrival 10-14 Request Ambulance or Rescue Squad 10-82 Hostage 10-15 Request Fire Department -

Property Type

The Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office’s Researchers Guide for Documenting and Evaluating Railroads Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 – 2 Property Type ................................................................................................................ 3 - 6 Description (Narrative, Mapping and Photography) .................................................. 7 - 8 Significance, History and Context Development ...................................................... 9 - 15 Integrity ...................................................................................................................... 17 - 19 Additional Avenues of Significance .......................................................................... 20 - 22 Glossary of Terms ...................................................................................................... 23 - 27 Appendix I - Naming Standardization Guide ................................................................. 28 Appendix 2 – Aggregate Files .................................................................................... 29-30 INTRODUCTION Railroads in Pennsylvania peaked at 11,693 miles of roadway in 1920, and Pennsylvania was generally considered to be the top third most railroad mileage state in the United States. Today, approximately 35% of all freight commerce in the nation still passes through Pennsylvania, consisting of approximately 5,500 miles of -

The Pennsylvania Railroad

The Pennsylvania Railroad THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD.. Spec. act of PA, April 12, 1846 Trackage, June 30, 1918: 2902.556 mi. First main track 1856.208 mi. Second main track 2928.284 mi. Yard track and sidings Equipment Steam locomotives 3,770 Extra tenders 128 Snowplows and flangers 116 Electric locomotives 68 Trailer cars 1 Freight cars 148,062 Passenger cars 3,853 Motor equipment of cars 183 Floating equipment 339 Work equipment 3,103 Miscellaneous equipment 221 Equipment leased from Goodman Car & Manufacturing Company: Work equipment 32 The Pennsylvania Railroad controls and operates the following companies: Company: Percent of control: Belvidere Delaware "majority" Connecting Railway "majority" Delaware River Railroad "majority" Harrison and East Newark “majority” Northern Central "majority" The Pennsylvania Railroad controls and operates the following companies except as noted: Company: Percent of control: Pennsylvania and Atlantic "majority" The portion from Pemberton to Hightstown, NJ is operated by The Union Transportation Co. Western New York and Pennsylvania Railway "majority" The portion from Mahoningtown to Stoneboro, PA, including a branch line from Leesburg to Redmond, PA The Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington Railroad "majority" The portion from Gray's Ferry to Eddystone, PA, operated by the Philadelphia and Reading Ry The Pennsylvania Railroad controls the following companies: Operated by their own organizations: Company: Percent of control: Cumberland Valley Rail Road "majority" Erie and Western Transportation Company -

Freight Rail

FREIGHTRAIL RAIL FREIGHT RAIL EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Pennsylvania’s 64 freight railroads operate on 5,604 miles of track across the state, ranking it the fifth largest rail network by mileage in the U.S. By 2035, 246 million tons of freight is expected to pass through the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, an increase of 22% over 2007 levels. Pennsylvania’s railroad freight demand continues to exceed current infrastructure. Improvements such as double stacking or parallel tracks and larger transfer facilities would help improve capacity. Despite competing interests , the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation’s Freight Rail Bureau has continued to procure impressive levels of freight infrastructure funding, which directly or indirectly supports multi modal transportation projects throughout the Commonwealth. This public funding is in addition to all private support committed. It has further produced the most comprehensive state rail plan to date, with a strong emphasis on understanding stakeholders and their needs. 2018 REPORT CARD FOR PENNSYLVANIA’S INFRASTRUCTURE—PAGE 42 BACKGROUND Since the mid-1800s, rail transportation has been a key transportation mode supporting industrial production and energy movement. Higher utilization of rail provides congestion mitigation benefits, air quality improvement, and enhancement of transportation safety, as a result of reducing truck traffic on highways. Pennsylvania has the 5th largest rail system in the United States and is one of the nation’s leaders in freight assessment, planning, and investment spurring from the Commonwealth’s industrial heritage. Today, most railroads are privately owned. The state network is made up of approximately 5,604 route-miles of freight railroad operated (Figure 1), and sixty-four freight railroads, more than any other state. -

Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA

Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA PREPARED FOR: Berks Alliance & Greater Reading Chamber Alliance PREPARED BY: Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc. July 2020 Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II CHAPTER 1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.2 PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVE 1-4 1.3 PROJECT SCOPE 1-4 1.4 PROJECT METHODOLOGY 1-5 1.5 FREIGHT RAILROAD PRINCIPLES 1-7 1.6 ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT 1-9 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY 2-1 2.1 HISTORY OF RAIL PASSENGER SERVICES IN READING 2-1 2.2 REVIEW OF PREVIOUS CORRIDOR STUDIES 2-1 CHAPTER 3 SERVICE AND OPERATING PLAN 3-1 3.1 INTRODUCTION 3-1 3.2 TRAIN TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS 3-3 3.3 PASSENGER TRAIN TIMETABLE DEVELOPMENT 3-7 3.4 RAIL CAPACITY NEEDS 3-17 3.5 SUMMARY 3-45 CHAPTER 4 CAPITAL PLAN 4-1 4.1 INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS 4-1 4.2 EQUIPMENT SCHEDULING AND CAPITAL COST 4-1 4.3 NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMPENSATION 4-1 4.4 EQUIPMENT AND TOTAL CAPITAL COST 4-1 CHAPTER 5 DEMOGRAPHICS, SOCIOECONOMIC AND TRANSPORTATION DATABASES 5-1 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5-1 5.2 ZONE SYSTEM 5-1 5.3 SOCIOECONOMIC DATABASE DEVELOPMENT 5-2 5.4 BASE YEAR TRANSPORTATION DATABASE DEVELOPMENT 5-4 CHAPTER 6 TRAVEL DEMAND FORECAST 6-1 6.1 FUTURE TRAVEL MARKET STRATEGIES 6-1 6.2 TRAVEL DEMAND FORECAST RESULTS 6-4 6.3 MARKET SHARES 6-10 6.4 BENCHMARKS 6-11 CHAPTER 7 OPERATING COSTS 7-1 TEMS, Inc. -

PHMC/BHP Researcher's Guide to Historic Railroads

The Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office’s Researchers Guide for Documenting and Evaluating Railroads October 16, 2015 Final Version Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................1 – 2 Property Type ............................................................................................................... 3 – 6 Documenting Contributing Resources to Historic Districts ............................................. 7 Description (Narrative, Mapping and Photography) .................................................. 8 - 9 Significance, History and Context Development ..................................................... 10 - 16 Integrity ...................................................................................................................... 17 - 19 Additional Avenues of Significance .......................................................................... 20 - 22 Glossary of Terms ...................................................................................................... 23 - 27 Appendix I - Naming Standardization Guide ................................................................. 28 Appendix 2 – Aggregate Files .................................................................................... 29-30 INTRODUCTION Railroads in Pennsylvania peaked at 11,693 miles of roadway in 1920, and Pennsylvania was generally considered to be the top third most railroad mileage state in the United States. Today, -

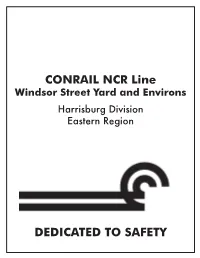

Windsor St Guide

CONRAIL NCR Line Windsor Street Yard and Environs Harrisburg Division Eastern Region DEDICATED TO SAFETY Buffalo Line To Buffalo & Erie Pittsburgh Line To Altoona Harrisburg Line To Reading Enola (Harrisburg) Lemoyne New Cumberland Marsh Run Lurgan Line To Hagerstown Middletown Ferry Keystone Corridor To Philadelphia Goldsboro Cly York Haven Wago Jct Wago Mount Wolf Emigsville Myers Mill Ewing York Industrial Yo r k Maryland & Pennsylvania Grantley Brillhart Spring Grove Glatfelter Frederick Secondary Smyser Hanover Jct. Seltzville Larue Hanover Glen Rock Seitzland Maryland Shrewsbury Midland Stewartstown RR New Freedom Summit Grove Freeland Box Tree Bentley Springs Walker Parkton Graystone White Hall Blue Mount Monkton Corbett Glencoe Sparks Phoenix Ashland Cockeysville Te x a s Padonia Timonium Lutherville Riderwood Ruxton Lake Roland Northeast Corridor To Philadelphia Mt. Washington Melvale Woodberry Mt. Vernon Baltimore Bayview Yard (Baltimore) CONRAIL’s NCR Line Northeast Corridor To Washington DC History Of The Northern Central The Northern Central Railway was originally built to give the city of Baltimore a competing Rail Line to the Baltimore and Ohio. It grew in importance through the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It carried passengers and freight north from Baltimore to meet up with the Pennsylvania’s main line to the Ohio River Valley. Early on, the Pennsylvania Railroad bought a controlling interest in the road and took over operations. The southern end (from Baltimore to Parkton MD) carried a large number of commuters in the early 20th century until the 30s when busses and automobiles took over much of this traffic. The line still carried high priority trains for Baltimore until the 50s when it started to really decline. -

Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA

Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA PREPARED FOR: Berks Alliance & Greater Reading Chamber Alliance PREPARED BY: Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc. July 2020 Restoring Passenger Rail Service to Berks County, PA Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS II CHAPTER 1 PROJECT OVERVIEW 1-1 1.1 INTRODUCTION 1-1 1.2 PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVE 1-4 1.3 PROJECT SCOPE 1-4 1.4 PROJECT METHODOLOGY 1-5 1.5 FREIGHT RAILROAD PRINCIPLES 1-7 1.6 ORGANIZATION OF THE REPORT 1-9 CHAPTER 2 BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY 2-1 2.1 HISTORY OF RAIL PASSENGER SERVICES IN READING 2-1 2.2 REVIEW OF PREVIOUS CORRIDOR STUDIES 2-1 CHAPTER 3 SERVICE AND OPERATING PLAN 3-1 3.1 INTRODUCTION 3-1 3.2 TRAIN TECHNOLOGY OPTIONS 3-3 3.3 PASSENGER TRAIN TIMETABLE DEVELOPMENT 3-7 3.4 RAIL CAPACITY NEEDS 3-17 3.5 SUMMARY 3-45 CHAPTER 4 CAPITAL PLAN 4-1 4.1 INFRASTRUCTURE NEEDS 4-1 4.2 EQUIPMENT SCHEDULING AND CAPITAL COST 4-1 4.3 NORFOLK SOUTHERN COMPENSATION 4-1 4.4 EQUIPMENT AND TOTAL CAPITAL COST 4-1 CHAPTER 5 DEMOGRAPHICS, SOCIOECONOMIC AND TRANSPORTATION DATABASES 5-1 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5-1 5.2 ZONE SYSTEM 5-1 5.3 SOCIOECONOMIC DATABASE DEVELOPMENT 5-2 5.4 BASE YEAR TRANSPORTATION DATABASE DEVELOPMENT 5-4 CHAPTER 6 TRAVEL DEMAND FORECAST 6-1 6.1 FUTURE TRAVEL MARKET STRATEGIES 6-1 6.2 TRAVEL DEMAND FORECAST RESULTS 6-4 6.3 MARKET SHARES 6-10 6.4 BENCHMARKS 6-11 CHAPTER 7 OPERATING COSTS 7-1 TEMS, Inc.