Turkish Historiography in Syria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2008-12 Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the divisive legacy of Sectarianism Francioch, Gregory A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3850 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS NATIONALISM IN OTTOMAN GREATER SYRIA 1840- 1914: THE DIVISIVE LEGACY OF SECTARIANISM by Gregory A. Francioch December 2008 Thesis Advisor: Anne Marie Baylouny Second Reader: Boris Keyser Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 1914: The Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism 6. AUTHOR(S) Greg Francioch 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

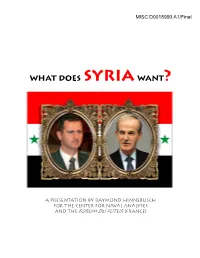

What Does Syria Want?

What Does Syria Want? A Presentation by Raymond Hinnebusch for the Center for Naval Analyses and the ForumForum dudu FuturFutur (france) 1 A Presentation by Raymond Hinnebusch for the Center for Naval Analyses and the Forum Du Futur (France) The distinguished American academic Raymond Hinnebusch, Director of the Centre for Syrian Studies and Professor of International Relations and Middle East Politics at the University of St. Andrews (UK), recently spoke at a France/U.S. dialogue in Paris co-sponsored by CNA and the Forum du Futur. Dr. Hinnebusch agreed to update his very thoughtful and salient presentation, “What Does Syria Want?” so that we might make it avail- able to a wider audience. The views expressed are his own and constitute an assessment of Syrian strategic think- ing. Raymond Hinnebusch may be contacted via e-mail at: [email protected] (Shown on the cover): A double portrait of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad (left) and his father (right), Hafez al-Assad, who was President of Syria from 1971-2000. 2 What Does Syria Want? the country and ideology of the ruling Ba’th party, is a direct consequence of this experience. By Raymond Hinnebusch Centre for Syrian Studies, “Syria is imbued with a powerful sense University of St. Andrews, (UK) of grievance from the history of its formation as a state.” With French President Nicholas Sarkozy’s invitation of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to Paris in July, More than that, from its long disillusioning experience 2008, the question of whether Syria is “serious” about with the West, Syria has a profoundly jaundiced view changing its ways and entitled to rehabilitation by the of contemporary international order, recently much re- international community, has become a matter of some inforced, which it sees as replete with double standards. -

The Political Ideas of Derviş Vahdeti As Reflected in Volkan Newspaper (1908-1909)

THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) by TALHA MURAT Submitted to the Graduate School of Social Sciences in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Sabancı University AUGUST 2020 THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) Approved by: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel . (Thesis Supervisor) Assist. Prof. Ayşe Ozil . Assist. Prof. Fatih Bayram . Date of Approval: August 10, 2020 TALHA MURAT 2020 c All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT THE POLITICAL IDEAS OF DERVİŞ VAHDETİ AS REFLECTED IN VOLKAN NEWSPAPER (1908-1909) TALHA MURAT TURKISH STUDIES M.A. THESIS, AUGUST 2020 Thesis Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Selçuk Akşin Somel Keywords: Derviş Vahdeti, Volkan, Pan-Islamism, Ottomanism, Political Islam The aim of this study is to reveal and explore the political ideas of Derviş Vahdeti (1870-1909) who was an important and controversial actor during the first months of the Second Constitutional Period (1908-1918). Starting from 11 December 1908, Vahdeti edited a daily newspaper, named Volkan (Volcano), until 20 April 1909. He personally published a number of writings in Volkan, and expressed his ideas on multiple subjects ranging from politics to the social life in the Ottoman Empire. His harsh criticism that targeted the policies of the Ottoman Committee of Progress and Union (CUP, Osmanlı İttihâd ve Terakki Cemiyeti) made him a serious threat for the authority of the CUP. Vahdeti later established an activist and religion- oriented party, named Muhammadan Union (İttihâd-ı Muhammedi). Although he was subject to a number of studies on the Second Constitutional Period due to his alleged role in the 31 March Incident of 1909, his ideas were mostly ignored and/or he was labelled as a religious extremist (mürteci). -

Next Steps in Syria

Next Steps in Syria BY JUDITH S. YAPHE early three years since the start of the Syrian civil war, no clear winner is in sight. Assassinations and defections of civilian and military loyalists close to President Bashar Nal-Assad, rebel success in parts of Aleppo and other key towns, and the spread of vio- lence to Damascus itself suggest that the regime is losing ground to its opposition. The tenacity of government forces in retaking territory lost to rebel factions, such as the key town of Qusayr, and attacks on Turkish and Lebanese military targets indicate, however, that the regime can win because of superior military equipment, especially airpower and missiles, and help from Iran and Hizballah. No one is prepared to confidently predict when the regime will collapse or if its oppo- nents can win. At this point several assessments seem clear: ■■ The Syrian opposition will continue to reject any compromise that keeps Assad in power and imposes a transitional government that includes loyalists of the current Baathist regime. While a compromise could ensure continuity of government and a degree of institutional sta- bility, it will almost certainly lead to protracted unrest and reprisals, especially if regime appoin- tees and loyalists remain in control of the police and internal security services. ■■ How Assad goes matters. He could be removed by coup, assassination, or an arranged exile. Whether by external or internal means, building a compromise transitional government after Assad will be complicated by three factors: disarray in the Syrian opposition, disagreement among United Nations (UN) Security Council members, and an intransigent sitting govern- ment. -

Herding, Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence

Herding,Warfare, and a Culture of Honor: Global Evidence* Yiming Cao† Benjamin Enke‡ Armin Falk§ Paola Giuliano¶ Nathan Nunn|| 7 September 2021 Abstract: According to the widely known ‘culture of honor’ hypothesis from social psychology, traditional herding practices have generated a value system conducive to revenge-taking and violence. We test the economic significance of this idea at a global scale using a combination of ethnographic and folklore data, global information on conflicts, and multinational surveys. We find that the descendants of herders have significantly more frequent and severe conflict today, and report being more willing to take revenge in global surveys. We conclude that herding practices generated a functional psychology that plays a role in shaping conflict across the globe. Keywords: Culture of honor, conflict, punishment, revenge. *We thank Anke Becker, Dov Cohen, Pauline Grosjean, Joseph Henrich, Stelios Michalopoulos and Thomas Talhelm for useful discussions and/or comments on the paper. †Boston University. (email: [email protected]) ‡Harvard University and NBER. (email: [email protected]) §briq and University of Bonn. (email: [email protected]) ¶University of California Los Angeles and NBER. (email: [email protected]) ||Harvard University and CIFAR. (email: [email protected]) 1. Introduction A culture of honor is a bundle of values, beliefs, and preferences that induce people to protect their reputation by answering threats and unkind behavior with revenge and violence. According to a widely known hypothesis, that was most fully developed by Nisbett( 1993) and Nisbett and Cohen( 1996), a culture of honor is believed to reflect an economically-functional cultural adaptation that arose in populations that depended heavily on animal herding (pastoralism).1 The argument is that, relative to farmers, herders are more vulnerable to exploitation and theft because their livestock is a valuable and mobile asset. -

Syria, April 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Syria, April 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: SYRIA April 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Syrian Arab Republic (Al Jumhuriyah al Arabiyah as Suriyah). Short Form: Syria. Term for Citizen(s): Syrian(s). Capital: Damascus (population estimated at 5 million in 2004). Other Major Cities: Aleppo (4.5 million), Homs (1.8 million), Hamah (1.6 million), Al Hasakah (1.3 million), Idlib (1.2 million), and Latakia (1 million). Independence: Syrians celebrate their independence on April 17, known as Evacuation Day, in commemoration of the departure of French forces in 1946. Public Holidays: Public holidays observed in Syria include New Year’s Day (January 1); Revolution Day (March 8); Evacuation Day (April 17); Egypt’s Revolution Day (July 23); Union of Syria, Egypt, and Libya (September 1); Martyrs’ Day, to commemorate the public hanging of 21 dissidents in 1916 (May 6); the beginning of the 1973 October War (October 6); National Day (November 16); and Christmas Day (December 25). Religious feasts with movable dates include Eid al Adha, the Feast of the Sacrifice; Muharram, the Islamic New Year; Greek Orthodox Easter; Mouloud/Yum an Nabi, celebration of the birth of Muhammad; Leilat al Meiraj, Ascension of Muhammad; and Eid al Fitr, the end of Ramadan. In 2005 movable holidays will be celebrated as follows: Eid al Adha, January 21; Muharram, February 10; Greek Orthodox Easter, April 29–May 2; Mouloud, April 21; Leilat al Meiraj, September 2; and Eid al Fitr, November 4. Flag: The Syrian flag consists of three equal horizontal stripes of red, white, and black with two small green, five-pointed stars in the middle of the white stripe. -

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(S): C

The Rise of Arabism in Syria Author(s): C. Ernest Dawn Source: Middle East Journal, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring, 1962), pp. 145-168 Published by: Middle East Institute Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4323468 Accessed: 27/08/2009 15:10 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mei. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Middle East Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Middle East Journal. http://www.jstor.org THE RISE OF ARABISMIN SYRIA C. Ernest Dawn JN the earlyyears of the twentiethcentury, two ideologiescompeted for the loyalties of the Arab inhabitantsof the Ottomanterritories which lay to the east of Suez. -

On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2019-01-03 On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada Alatrash, Ghada Alatrash, G. (2019). On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/109417 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY On the Lived Experience of the Syrian Diaspora in Canada by Ghada Alatrash A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2019 © Ghada Alatrash 2019 Abstract The Syrian Diaspora today is a complex topic that speaks to issues of dislocation, displacement, loss, exile, identity, resilience and a desire for belonging. My research sought to better understand these issues and the lived experience and human condition of the Syrian Diaspora. In my research, I thought through this main question: How do Syrian newcomers come to make sense of what it means to have lost a home and a homeland as it relates to the Syrian Diasporic experience? I broached the Syrian diasporic subject by thinking through an anti-Orientalist, anti- colonial framework, and I engaged autoethnography as a research methodology and as a method as I reflexively thought through and wrote from my own personal experience as a Syrian immigrant so that I could better understand the Syrian refugee’s human experience. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe. -

The Plight of Palestinian Refugees in Syria in the Camps South of Damascus by Metwaly Abo Naser, with the Support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill

Expert Analysis January 2017 Syrian voices on the Syrian conflict: The plight of Palestinian refugees in Syria in the camps south of Damascus By Metwaly Abo Naser, with the support of Ryme Katkhouda and Devorah Hill Introduction: the historical role of Palestinians the Oslo Accords in 1992 and the resulting loss by both the in Syria Palestinian diaspora in general and the inhabitants of the After they took refuge in Syria after the 1948 war, al-Yarmouk refugee camp in particular of their position as Palestinians refugees were treated in the same way as a key source of both material and ideological support for other Syrian citizens. Their numbers eventually reached the Palestinian armed revolution in the diaspora. This was 450,000, living mostly in 11 refugee camps throughout Syria due in part to the failure of the various Palestinian national (UNRWA, 2006). Permitted to fully participate in the liberation factions to identify new ways of engaging the economic and social life of Syrian society, they had the diaspora – including the half million Palestinians living in same civic and economic rights and duties as Syrians, Syria – in the Palestinian struggle for the liberation of the except that they could neither be nominated for political land occupied by Israel. office nor participate in elections. This helped them to feel that they were part of Syrian society, despite their refugee This process happened slowly. After the Israeli blockade of status and active role in the global Palestinian liberation Lebanon in 1982, the Palestinian militant struggle declined. struggle against the Israeli occupation of their homeland. -

The Case of Said Nursi

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi Zubeyir Nisanci Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Nisanci, Zubeyir, "The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi" (2015). Dissertations. 1482. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1482 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Zubeyir Nisanci LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE DIALECTICS OF SECULARISM AND REVIVALISM IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF SAID NURSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY BY ZUBEYIR NISANCI CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Zubeyir Nisanci, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to Dr. Rhys H. Williams who chaired this dissertation project. His theoretical and methodological suggestions and advice guided me in formulating and writing this dissertation. It is because of his guidance that this study proved to be a very fruitful academic research and theoretical learning experience for myself. My gratitude also goes to the other members of the committee, Drs. Michael Agliardo, Laureen Langman and Marcia Hermansen for their suggestions and advice. -

3 on Understanding Syrian Diasporic Identities Through a Selection Of

On Understanding Syrian Diasporic Identities through a Selection of Syrian Literary Works Ghada Alatrash Mount Royal University [email protected] Najat Abed Alsamad [email protected] Abstract As of late August 2018, a total of 58,600 Syrian refugees have arrived in Canada (Government of Canada, 2019). The Syrian Diaspora today is a complex topic that speaks to issues of dislocation, displacement, loss, exile, identity, a desire for belonging, and resilience. The aim of this paper is to offer a better understanding of the Syrian peoples who have become, within the past four years, part of our Canadian citizenry, local communities, and members of our schools and workforce. By engaging the voices of Syrians through their literary works, this essay seeks to challenge some of the ontological and epistemological underpinnings that have historically defined Syrians and to offer alternate ways in which we may better know and understand what it means to be Syrian today. Historically Syrians have written and spoken about exile in their literature, long before the the Syrian war began in March of 2011. To deliver a sense of Syrian identities, a selected number of pre-Syrian-war writers and poets are engaged in this essay, including Nizar Kabbani, Muhammad al-Maghut, Zakaria Tamer, Mamduh Adwan, Adonis and Nasib Arida; furthermore, to capture a glimpse of a post-war sentiment, the voice of Syrian novelist Najat Abdul Samad, whose work was written from within the national borders of a war- torn Syria, is brought into the discussion. Introduction “‘Syria has become the great tragedy of this century - a disgraceful humanitarian calamity with suffering and displacement unparalleled in recent history,’ said Antonio Guterres, head of the UN High Commission for Refugees” (Watt, Blair, & Sherlock, 2013).