Concentrated Poverty Neighborhoods in Los Angeles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments

Historic-Cultural Monument (HCM) List City Declared Monuments No. Name Address CHC No. CF No. Adopted Community Plan Area CD Notes 1 Leonis Adobe 23537 Calabasas Road 08/06/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 3 Woodland Hills - West Hills 2 Bolton Hall 10116 Commerce Avenue & 7157 08/06/1962 Sunland - Tujunga - Lake View 7 Valmont Street Terrace - Shadow Hills - East La Tuna Canyon 3 Plaza Church 535 North Main Street and 100-110 08/06/1962 Central City 14 La Iglesia de Nuestra Cesar Chavez Avenue Señora la Reina de Los Angeles (The Church of Our Lady the Queen of Angels) 4 Angel's Flight 4th Street & Hill Street 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Dismantled May 1969; Moved to Hill Street between 3rd Street and 4th Street, February 1996 5 The Salt Box 339 South Bunker Hill Avenue (Now 08/06/1962 Central City 14 Moved from 339 Hope Street) South Bunker Hill Avenue (now Hope Street) to Heritage Square; destroyed by fire 1969 6 Bradbury Building 300-310 South Broadway and 216- 09/21/1962 Central City 14 224 West 3rd Street 7 Romulo Pico Adobe (Rancho 10940 North Sepulveda Boulevard 09/21/1962 Mission Hills - Panorama City - 7 Romulo) North Hills 8 Foy House 1335-1341 1/2 Carroll Avenue 09/21/1962 Silver Lake - Echo Park - 1 Elysian Valley 9 Shadow Ranch House 22633 Vanowen Street 11/02/1962 Canoga Park - Winnetka - 12 Woodland Hills - West Hills 10 Eagle Rock Eagle Rock View Drive, North 11/16/1962 Northeast Los Angeles 14 Figueroa (Terminus), 72-77 Patrician Way, and 7650-7694 Scholl Canyon Road 11 The Rochester (West Temple 1012 West Temple Street 01/04/1963 Westlake 1 Demolished February Apartments) 14, 1979 12 Hollyhock House 4800 Hollywood Boulevard 01/04/1963 Hollywood 13 13 Rocha House 2400 Shenandoah Street 01/28/1963 West Adams - Baldwin Hills - 10 Leimert City of Los Angeles May 5, 2021 Page 1 of 60 Department of City Planning No. -

Of Mallbu ~~~— I 23825 Stuart Ranch Road •Malibu, California• 90265-4861 ,~.`~~~~, (310)456-2489 •Fax(310) 456-7650 • °~+T~ Nma~

~~~~ ~~Z1 ~'~~ '~\ ~ r ~- ~ ~ ~1ty of Mallbu ~~~— i 23825 Stuart Ranch Road •Malibu, California• 90265-4861 ,~.`~~~~, (310)456-2489 •Fax(310) 456-7650 • www.malibucity.org °~+t~ nMa~ October 22, 2013 Glen Campora, Assistant Deputy Director California Department of Housing and Community Development 2020 W. EI Camino Avenue Sacramento, CA 95833 Subject: City of Malibu 2013-2021 Draft Housing Element(5 t" cycle) Dear Mr. Campora: The City of Malibu is pleased to submit its draft 5th cycle Housing Element for your review. The element has been revised to update the analysis of need, resources, constraints and programs to reflect current circumstances. Since the City's 4th cycle Housing Element was found to be in compliance and all zoning implementation programs have been completed, the City requesfs a streamlined review of the new element. If you have any questions, please contact me at 310-456-2489, extension 265, or the 'City's consultant, John Douglas, at 714-628-0464. We appreciate the assistance of Jess Negrete during the 4th cycle and look forward to receiving your review letter. Sincerely, 1 ~: !, <_ .~ Joyce Parker-Bozylinski, AICP Planning Director Enclosures: Draft 2013-2021 Malibu Housing Element(5 th cycle) Implementation Review Completeness Checklist HCD Streamline Review Form CITY OF MALIBU 2013-20212008 - 2013 Housing Element Draft October 2013 August 26, 2013 City Council Resolution No. 13-34 This page intentionally left blank City of Malibu 2013-20212008-2013 Housing Element Contents I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. I-1 A. Purpose of the Housing Element ............................................................................................ I-1 B. Public Participation ................................................................................................................... I-2 C. Consistency with Other Elements of the General Plan ..................................................... -

Bow Tie Yard Lofts Project Initial Study

City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning Major Projects & Environmental Analysis Section City Hall 200 N. Spring Street, Room 750 Los Angeles, CA 90012 INITIAL STUDY Northeast Los Angeles Community Plan Area Bow Tie Yard Lofts Project Case Number: ENV-2016-2862-EIR Project Location: 2750-2800 W. Casitas Avenue, Los Angeles, California 90039 Council District: 1, Gilbert A. Cedillo Project Description: The Applicant proposes the development of a mixed-use project in the Northeast Los Angeles Community Plan area that would consist of five buildings with a total of 419 multi-family residential units (approximately 423,872 square feet) and approximately 64,000 square feet of commercial space. The 5.7-acre Project Site is located at the terminus of Casitas Avenue in Glassell Park in Northeast Los Angeles. The Los Angeles River is adjacent to the Project Site’s southern boundary line, and the Glendale Freeway (SR-2) is located to the north and west of the Project Site. The existing zoning designation of the Project Site is [Q]PF-1-CDO-RIO. Existing on-site uses, including a light manufacturing/warehouse/film production building (approximately 117,000 square feet) and its associated surface parking, would be demolished as part of the Proposed Project. The proposed residential units would include a combination of 119 studios, 220 one-bedroom, and 80 two-bedroom units in four buildings ranging from five to six stories (60 to 81 feet above grade). Eleven percent of the base-density residential units (approximately 35 units) would be reserved as Very Low Income Units. -

Poverty and Place in the Context of the American South by Regina

Poverty and Place in the Context of the American South by Regina Smalls Baker Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ David Brady, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Linda M. Burton, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva ___________________________ Kenneth C. Land Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 ABSTRACT Poverty and Place in the Context of the American South by Regina Smalls Baker Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ David Brady, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Linda M. Burton, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Eduardo Bonilla-Silva ___________________________ Kenneth C. Land An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2015 Copyright by Regina Smalls Baker 2015 Abstract In the United States, poverty has been historically higher and disproportionately concentrated in the American South. Despite this fact, much of the conventional poverty literature in the United States has focused on urban poverty in cities, particularly in the Northeast and Midwest. Relatively less American poverty research has focused on the enduring economic distress in the South, which Wimberley (2008:899) calls “a neglected regional crisis of historic and contemporary urgency.” Accordingly, this dissertation contributes to the inequality literature by focusing much needed attention on poverty in the South. Each empirical chapter focuses on a different aspect of poverty in the South. Chapter 2 examines why poverty is higher in the South relative to the Non-South. -

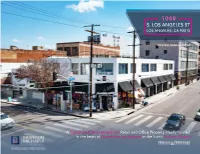

1048 S Los Angeles Street Is Located Less Than Three Miles from the Ferrante, a Massive 1,500-Unit Construction Project, Scheduled for Completion in 2021

OFFERING MEMORANDUM A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District brandonmichaelsgroup.com INVESTMENT ADVISORS Brandon Michaels Senior Managing Director of Investments Senior Director, National Retail Group Tel: 818.212-2794 [email protected] CA License: 01434685 Matthew Luchs First Vice President Investments COO of The Brandon Michaels Group Tel: 818.212.2727 [email protected] CA License: 01948233 Ben Brownstein Senior Investment Associate National Retail Group National Industrial Properties Group Tel: 818.212.2812 [email protected] CA License: 02012808 Contents 04 Executive Summary 10 Property Overview 16 Area Overview 28 FINANCIAL ANALYSIS Executive Summary 4 1048 S. Los Angeles St The Offering A Signalized Corner Mixed-Use Retail and Office Property Ideally located in the heart of Downtown Los Angeles in the Iconic Fashion District The Brandon Michaels Group of Marcus & Millichap has been selected to exclusively represent for sale 1048 South Los Angeles Street, a two-story multi-tenant mixed-use retail and office property ideally located on the Northeast signalized corner of Los Angeles Street and East 11th Street. The property is comprised of 15 rental units, with eight retail units on the ground floor, and seven office units on the second story. 1048 South Los Angeles Street is to undergo a $170 million renovation. currently 86% occupied. Three units are The property is located in the heart of vacant, one of which is on the ground the iconic fashion district of Downtown floor, and two of which are on the Los Angeles, which is home to over second story. -

Downtownla VISION PLAN

your downtownLA VISION PLAN This is a project for the Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council with funding provided by the Southern California Association of Governments’ (SCAG) Compass Blueprint Program. Compass Blueprint assists Southern California cities and other organizations in evaluating planning options and stimulating development consistent with the region’s goals. Compass Blueprint tools support visioning efforts, infill analyses, economic and policy analyses, and marketing and communication programs. The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grant(s) from the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) and the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) through the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) in accordance with the provisions under the Metropolitan Planning Program as set forth in Section 104(f) of Title 23 of the U.S. Code. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do not necessarily reflect the official views or policies of SCAG, DOT or the State of California. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. SCAG shall not be responsible for the City’s future use or adaptation of the report. 0CONTENTS 00. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 01. WHY IS DOWNTOWN IMPORTANT? 01a. It is the birthplace of Los Angeles 01b. All roads lead to Downtown 01c. It is the civic, cultural, and commercial heart of Los Angeles 02. WHAT HAS SHAPED DOWNTOWN? 02a. Significant milestones in Downtown’s development 02b. From pueblo to urban core 03. DOWNTOWN TODAY 03a. Recent development trends 03b. Public infrastructure initiatives 04. -

17-Unit Small Lot Subdivision Development Opportunity in Los Angeles’ Eagle Rock Neighborhood

4035 EAGLE ROCK BOULEVARD LOS ANGELES, CA 90065 17-unit small lot subdivision development opportunity in Los Angeles’ Eagle Rock neighborhood. CONFIDENTIALITY AND DISCLAIMER The information contained in the following Marketing Brochure is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Marcus & Millichap and should not be made available to any other person or entity without the written consent of Marcus & Millichap. This Marketing Brochure has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Marcus & Millichap has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial performance of the property, the size and square footage of the property and improvements, the presence or absence of contaminating substances, PCB’s or asbestos, the compliance with State and Federal regulations, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. The information contained in this Marketing Brochure has been obtained from sources we believe to be reliable; however, Marcus & Millichap has not verified, and will not verify, any of the information contained herein, nor has Marcus & Millichap conducted any investigation regarding these matters and makes no warranty or representation whatsoever regarding the accuracy or completeness of the information provided. -

City of Los Angeles Mayor's Office of Economic Development

SOUTH LOS ANGELES COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY Prepared for City of Los Angeles Mayor’s Office of Economic Development Submitted by Figueroa Media Group World Innovations Marketing Los Angeles Harbor-Watts EDC South Los Angeles Economic Alliance USC Center for Economic Development March 2001 COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY ii REPORT PRODUCED BY THE USC CENTER FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Leonard Mitchell, Esq., Director Deepak Bahl, Associate Director Thomas O’Brien, Research Associate Paul Zamorano-Reagin, Research Associate 385 Von KleinSmid Center Los Angeles, California 90089 (213) 740-9491 http://www.usc.edu/schools/sppd/ced SOUTH LOS ANGELES i THE SOUTH LOS ANGELES COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY PROJECT TEAM Figueroa Media Group Keith Coleman Nathan Freeman World Innovations Marketing Leticia Galindo Zully Gonzalez Los Angeles Harbor-Watts EDC Reynold Blight South Los Angeles Economic Alliance Bill Raphiel USC Center for Economic Development Leonard Mitchell, Esq. Deepak Bahl Thomas O’Brien Paul Zamorano-Reagin COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The South Los Angeles Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy Project Team gratefully acknowledges the assistance of: The Mayor’s Office of Economic Development John De Witt, Director Infrastructure Investment Ronald Nagai, Senior Project Manager Susan Cline, Planning Project Manager The Office of Councilmember Ruth Galanter, Sixth District Audrey King, Field Deputy Tracey Warden, Legislative Deputy The Office of Councilmember -

The State of Asian and Pacific Cities 2015 Urban Transformations Shifting from Quantity to Quality

The State of Asian and Pacific Cities 2015 Urban transformations Shifting from quantity to quality The State of Asian and Pacific Cities 2015 Urban transformations Shifting from quantity to quality © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), 2015 © The United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP), 2015 Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the Governing Council of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme or its Member States. Reference to names of firms and commercial products and processes do not imply their endorsement by the United Nations. Excerpts from this publication, excluding photographs, may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. All photos courtesy of dreamstime.com other than pp. 19, 23, 28, 31, 44, 66, 73, 120, 133, 135, 152, 164, 165 and 172 where copyright is indicated. HS Number: HS/071/15E ISBN: (Volume) 978-92-1-132681-9 Cover image: A bridge on the Pearl River, Guangzhou © Lim Ozoom/Dreamstime Design and Layout -

THE TRI NGLE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY at South Market Place in the REVITALIZED CITY of INGLEWOOD

RARE MIXED-USE THE TRI NGLE DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY at South Market Place IN THE REVITALIZED CITY OF INGLEWOOD BARBARA ARMENDARIZ President & Founder CalDRE #01472088 213.266.3333 x404 501, 509 & 513 S LA BREA AVE [email protected] 425, 451, 467 & 475 S MARKET ST This conceptual design is based upon a preliminary review of entitlement requirements INGLEWOOD, CAand on unverified 90301 and possibly incomplete site and/or building information, and is EAST HILLCREST BLVD + SOUTH LABREA AVE PERSPECTIVE intended merely to assist in exploring how the project might be developed. Signage PAGE THE TRIANGLE AT S. MARKET PLACE 05.07.2020 shown is for illustrative purposes only and does not necessarily reflect municipal 3 code compliance. All colors shown are for representative purposes only. Refer to INGLEWOOD, CA - LAX20-0000-00 material samples for actual color verification. DISCLAIMER All materials and information received or derived from SharpLine Commercial Partners its directors, officers, agents, advisors, affiliates and/or any third party sources are provided without representation THE TRI NGLE or warranty as to completeness , veracity, or accuracy, condition of the property, compliance or lack of compliance with applicable governmental requirements, developability or suitability, financial at South Market Place performance of the property, projected financial performance of the property for any party’s intended use or any and all other matters. TABLE of CONETNTS Neither SharpLine Commercial Partners its directors, officers, agents, advisors, or affiliates makes any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to accuracy or completeness of the any materials or information provided, derived, or received. Materials and information from any source, whether written or verbal, that may be furnished for review are not a substitute for a party’s active conduct of Executive Summary 03 its own due diligence to determine these and other matters of significance to such party. -

Black, Poor, and Gone: Civil Rights Law's Inner-City Crisis

\\jciprod01\productn\H\HLC\54-2\HLC204.txt unknown Seq: 1 21-JUN-19 10:37 Black, Poor, and Gone: Civil Rights Law’s Inner-City Crisis Anthony V. Alfieri* In recent years, academics committed to a new law and sociology of pov- erty and inequality have sounded a call to revisit the inner city as a site of cultural and socio-legal research. Both advocates in anti-poverty and civil rights organizations, and scholars in law school clinical and university social policy programs, have echoed this call. Together they have embraced the inner city as a context for experiential learning, qualitative research, and legal-political ad- vocacy regarding concentrated poverty, neighborhood disadvantage, residential segregation, and mass incarceration. Indeed, for academics, advocates, and ac- tivists alike, the inner city stands out as a focal point of innovative theory-prac- tice integration in the fields of civil and criminal justice. Today, in the post-civil rights era, new socio-legal research on the inner city casts a specially instructive light on the past, present, and future work of community-based advocacy groups, anti-poverty and civil rights organizations, and law school clinical programs. That light illuminates the socioeconomic con- ditions that cause and perpetuate poverty, and, equally important, the govern- ment (federal, state, and local) policies and practices that spawn mass eviction and reinforce residential segregation. Widely adopted by municipalities, those displacement-producing and segregation-enforcing policies and practices— neighborhood zoning, land use designation, building condemnation and demoli- tion, and housing code under- or over-enforcement—have caused and will con- tinue to cause the involuntary removal of low-income tenants and homeowners from gentrifying urban spaces and their forced out-migration to impoverished suburban spaces. -

20) Medium Clubs (20-40) Large Clubs (41+) Award Name Small

Rotary District 5260 2006-07 Awards Program CLUB SERVICE Small Clubs (<20) Medium Clubs (20-40) Large Clubs (41+) Antelope Valley Sunrise Bishop Sunrise Bishop Atwater Silverlake Sunrise Canoga Park Burbank Burbank Sunrise La Cañada Flintridge Glendale Calabasas Lancaster Glendale Sunrise Crescenta Valley Lancaster Sunrise Granada Hills Northeast Los Angeles Mammoth Lakes Sunrise Lancaster West Northridge/Chatsworth Mid San Fernando Valley Mammoth Lakes Palmdale North Hollywood Santa Clarita Valley Rosamond North San Fernando Valley Woodland Hills Santa Clarita Sunrise Studio City-Sherman Oaks Sun Valley Tarzana Encino Sunland-Tujunga Van Nuys Universal City-Sunrise Warner Center Award Name Small Club Winner Medium Club Winner Large Club Winner Best Overall Club Service Award Antelope Valley Sunrise Lancaster Rotary Lancaster West 2nd Place Overall Service Atwater Silverlake Sunrise Warner Center Glendale Sunrise 3rd Place Overall Service Santa Clarita Sunrise Bishop Sunrise Granada Hills Superior Avenue of Service (best single project) SCS - Hurrican Fundraiser Lancaster - Reverse raffle $12K Lancaster-W auction $50K &19 PHF 2nd Place Service Project (2nd best single project) ATS - 8 PHF Tarzana - 7 New member Granada Hills - Bowling $13K 3rd Place Service Project (3 best single project) Palmdale - Fireworks fundraiser MSFV - Local 300 - Scholarships GSR - 16 New members CinAC / Golf $12K Stand-Out Public Relations Award ASSRC - PR/Bulletin/Website Lancaster - Antelope Valley Fair Lancaster-W Lobster fest & Radio broadcast Perfect Partnership