National Reconstruction in Guinea-Bissau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal by Nikolas Sweet a Dissertation Submitte

The Poetics of Relationality: Mobility, Naming, and Sociability in Southeastern Senegal By Nikolas Sweet A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee Professor Judith Irvine, chair Associate Professor Michael Lempert Professor Mike McGovern Professor Barbra Meek Professor Derek Peterson Nikolas Sweet [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-3957-2888 © 2019 Nikolas Sweet This dissertation is dedicated to Doba and to the people of Taabe. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The field work conducted for this dissertation was made possible with generous support from the National Science Foundation’s Doctoral Dissertation Research Improvement Grant, the Wenner-Gren Foundation’s Dissertation Fieldwork Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Graduate Research Fellowship Program, and the University of Michigan Rackham International Research Award. Many thanks also to the financial support from the following centers and institutes at the University of Michigan: The African Studies Center, the Department of Anthropology, Rackham Graduate School, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, the Mellon Institute, and the International Institute. I wish to thank Senegal’s Ministère de l'Education et de la Recherche for authorizing my research in Kédougou. I am deeply grateful to the West African Research Center (WARC) for hosting me as a scholar and providing me a welcoming center in Dakar. I would like to thank Mariane Wade, in particular, for her warmth and support during my intermittent stays in Dakar. This research can be seen as a decades-long interest in West Africa that began in the Peace Corps in 2006-2009. -

Da Guiné-Bissau. Ii. Papilionidae E Pieridae

Boletín Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa, n1 41 (2007) : 223–236. NOVOS DADOS SOBRE OS LEPIDÓPTEROS DIURNOS (LEPIDOPTERA: HESPERIOIDEA E PAPILIONOIDEA) DA GUINÉ-BISSAU. II. PAPILIONIDAE E PIERIDAE A. Bivar-de-Sousa1, L.F. Mendes2 & S. Consciência3 1 Sociedade Portuguesa de Entomologia, Apartado 8221, 1803-001 Lisboa, Portugal. – [email protected] 2 Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (IICT-IP), JBT, Zoologia, R. da Junqueira, 14, 1300-343 Lisboa, Portugal. – [email protected] 3 Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (IICT-IP), JBT, Zoologia, R. da Junqueira, 14, 1300-343 Lisboa, Portugal. – [email protected] Resumo: Estudam-se amostras de borboletas diurnas das famílias Papilionidae e Pieridae colhidas ao longo da Guiné-Bissau, no que corresponde à nossa segunda contribuição para o conhecimento das borboletas diurnas deste país. Na sua maioria o material encontra-se depositadas na colecção aracno-entomológica do IICT e na colecção particular do primeiro co-autor, tendo-se reexaminado as amostras determinadas por Bacelar (1949). Em simultâneo, actualizam-se os conhecimentos sobre a fauna de lepidópteros ropalóceros do Parque Natural das Lagoas de Cufada (PNLC). A distribuição geográfica conhecida de cada uma das espécies no país é representada em mapas UTM com quadrícula de 10 Km de lado. Referem-se três espécies de Papilionidae e um género e quatro espécies de Pieridae como novidades faunísticas para a Guiné-Bissau e três espécies de Papilionidae e dois géneros e sete espécies de Pieridae são novas para o PNLC, no total das trinta e uma espécies até ao momento encontradas nestas famílias (nove, e vinte e duas, respectivamente) no país. Palavras chave: Lepidoptera, Papilionidae, Pieridae, distribuição geográfica, Guiné-Bissau. -

Guinea Bissau Ebola Situation Report

Picture goes here Resize before including pictures or maps in the Guinea Bissau SitRep *All Ebola statistics in this report are drawn The SitRep should not exceed 3mb total from the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare (MoHSW) Ebola SitRep #165, which Ebolareports cumulative cases as of 27 October 2014 (from 23 May toSituation 27 October 2014). Report 12 August 2015 HIGHLIGHTS SITUATION IN NUMBERS Owing to a fragile health system in Guinea-Bissau establishing a sanitary As of 12 August 2015 corridor along the border regions, the islands and the capital Bissau, continues to be a major challenge 500,000 As a trusted partner in Guinea Bissau, UNICEF continues to perform and Children living in high risk areas deliver its programme, maintaining relations with all sectors of the government, and providing technical assistance in ensuring systems are in place in case of a potential Ebola crisis UNICEF funding needs until August 2015 UNICEF provides strong support to the government and people in USD 5,160,712 million Guinea-Bissau in Ebola prevention on several fronts. Actions this week focused on trainings in Education, Protection and C4D (Youth). UNICEF funding gap USD 1,474,505 million Community engagement initiatives continued to be implemented with UNICEF support, focusing but not limited to high risk communities of Gabu and Tombali, bordering Guinea Conakry. The activities are implemented through a network of local NGOs, community based organisations, Christian and Islamic church-based organizations, the Traditional Leaders Authority, the Association of Traditional Healers PROMETRA, the taxi drivers unions SIMAPPA and community radios. Several meetings were held with government and civil society counterparts both in Bissau and in Gabu province, with an emphasis on securing a commitment for more thorough coordination among partners, particularly given the entry of new players in the country, and to avoid potential duplication of efforts. -

Guinea-Bissau Protracted Relief and Recovery Operation 200526

!"#!$ % %&& $# "!#'!# &&! #%% Number of beneficiaries 157,000 (annual average) 23 months Duration of project (March 2013-January 2014) WFP food tonnage 11,419 mt Cost (United States dollars) WFP food cost US$7,411,514 Total cost to WFP US$15,294,464 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Guinea-Bissau is one of the poorest countries in the world, where the prevalence of malnutrition and food insecurity is persistently high. Political instability has led to severe disruption and suspension of United Nations development programmes with the exception of humanitarian interventions. The Transitional Government appointed by the military command is not yet recognized by the majority of the international community. Given this impasse, the United Nations country team has postponed the start of the new United Nation Development Framework cycle from 2013 to 2015, with the expectation that constitutional order will be restored in the meantime. Hence, the start of the WFP country programme planned for January 2013 has also been postponed until 2015. To bridge this period, this protracted relief and recovery operation is proposed to maintain essential food security and nutrition activities in 2013-2014. A rapid food security assessment in mid-2012 revealed worsening food security with households increasingly resorting to negative coping strategies, such as the reduction of the number of meals, and sale of household assets. The prevalence of global acute malnutrition is considered “poor” at 6 percent nationally, reaching up to 8 percent at the regional level. In line with WFP Strategic Objective 3 (“Restore and rebuild lives and livelihoods in post- conflict, post-disaster or transition situations”), this operation will support vulnerable groups and communities affected by the post-election crisis, with the aim to address malnutrition, strengthen human capital through education, and rebuild livelihoods. -

MOROCCO and ECOWAS: Picking Cherries and 32 Dismantling Core Principles

www.westafricaninsight.org V ol 5. No 2. 2017 ISSN 2006-1544 WestIAN fSrI iGcHaT MOROCCO’s ACCESSION TO ECOWAS Centre for Democracy and Development TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial 2 ECOWAS Expansion Versus Integration: Dynamics and Realities 3 ISSUES AND OPTIONS In Morocco's Quest to 11 join the ECOWAS THE ACCESSION of The Kingdom of Morocco to the Economic Community 20 of West African States MOROCCO‟s APPLICATION TO JOIN ECOWAS: A SOFT-POWER ANALYSIS 27 MOROCCO AND ECOWAS: Picking Cherries and 32 Dismantling Core Principles Centre for Democracy and Development W ebsit e: www .cddw estafrica.or g 16, A7 Street, Mount Pleasant Estate, : [email protected] Jabi-Airport Road, Mbora District, : @CDDWestAfrica Abuja, FCT. P.O.Box 14385 www.facebook.com 234 7098212524 Centr efor democracy .anddev elopment Kindly send us your feed back on this edition via: [email protected] Cover picture source: Other pictures source: Internet The Centre for Democracy and Development and the Open Society Initiative for West Africa are not responsible for the views expressed in this publication Chukwuemeka Eze makes the argument that Editorial Morocco's application to join ECOWAS is moved by his December, the Economic Community of self-interest. Morocco is seeking to position itself as a West African States (ECOWAS) has to decide continental power sitting at the top of the political whether Morocco's application to join should and economic table in Africa. By joining ECOWAS T Morocco would have additional opportunities and be accepted or thrown out. Jibrin Ibrahim makes the case that ECOWAS should not allow itself to be benefits in the international community and would stampeded into accepting Morocco into its fold also benefit from the Arab League quota as well as without thinking through the implications for its core West African quota. -

View of Race and Culture, Winter, 1957

71-27,438 BOSTICK, Herman Franklin, 1929- THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL . CURRICULUM: A TEACHER'S GUIDE. I The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1971 Education, curriculum development. I i ( University Microfilms, A XEROKCompany, Ann Arbor, Michigan ©Copyright by Herman Franklin Bostick 1971 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE INTRODUCTION OF AFRO-FRENCH LITERATURE AND CULTURE IN THE AMERICAN SECONDARY SCHOOL CURRICULUM; A TEACHER'S GUIDE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Herman Franklin Bostick, B.A., M.A. The Ohio State University Approved by College of Education DEDICATION To the memory of my mother, Mrs. Leola Brown Bostick who, from my earliest introduction to formal study to the time of her death, was a constant source of encouragement and assistance; and who instilled in me the faith to persevere in the face of seemingly insurmountable obstacles, I solemnly dedicate this volume. H.F.B. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS To list all of the people who contributed in no small measure to the completion of this study would be impossible in the limited space generally reserved to acknowledgements in studies of this kind. Therefore, I shall have to be content with expressing to this nameless host my deepest appreciation. However, there are a few who went beyond the "call of duty" in their assistance and encouragement, not only in the preparation of this dissertation but throughout my years of study toward the Doctor of Philosophy Degree, whose names deserve to be mentioned here and to whom a special tribute of thanks must be paid. -

Negotiating Development: Valuation of a Guesthouse Project in Southern Guinea-Bissau

Journal of International and Global Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Article 5 11-1-2014 Negotiating Development: Valuation of a Guesthouse Project in Southern Guinea-Bissau Brandon Lundy Ph.D. Kennesaw State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs Part of the Anthropology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Environmental Studies Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Lundy, Brandon Ph.D. (2014) "Negotiating Development: Valuation of a Guesthouse Project in Southern Guinea-Bissau," Journal of International and Global Studies: Vol. 6 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lindenwood.edu/jigs/vol6/iss1/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of International and Global Studies by an authorized editor of Digital Commons@Lindenwood University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Negotiating Development: Valuation of a Guesthouse Project in Southern Guinea-Bissau1 Brandon D. Lundy, PhD Kennesaw State University [email protected] Abstract This paper provides a case study illustrating the crossroads between the agendas of international/national economic development with that of the development objectives of local communities. It shows how a community development project connects villagers to the larger world – both practically and imaginatively. This study takes a single case, the process of developing a guesthouse building project among the Nalú of southern Guinea-Bissau, to illustrate how a local attempt to connect to the outside world is intersected by community relations, NGOs, and development discourse. -

Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: the Group of Women Facilitators

Monday street market in downtown Bissau, November 13, 2017. Bissau, Guinea-Bissau Photo: Beatriz Bechelli Policy Brief Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: The Group of Women Facilitators Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute IGARAPÉ INSTITUTE | POLICE BRIEF | APRIL 2018 Policy Brief Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: Group of Women Facilitators Adriana Erthal Abdenur, Igarapé Institute1 Key Recommendations • Identify the challenges and opportunities inherent to participating in the Group of Women Mediators (GMF) and how hurdles could be overcome. • Ensure the personal safety of the group’s current and prospective members and support ways to make it feasible for the women to participate on an ongoing basis. • Support and encourage the safe documentation of the GMF activities. • Promote stronger linkages to other women’s groups in Guinea-Bissau, including the Network of Women Mediators and the Network of Parliamentary Women (Rede de Mulheres Parlamentares, RMP). • Strengthen links to regional organizations such as WIPNET and ECOWAS and to global institutions such as the UN, especially via the UNWomen, DPA, and UNIOGBIS, focusing on capacity-building, knowledge-sharing, and drawing lessons learned. • Promote South-South cooperation on mediation and facilitation by creating links to other women’s groups elsewhere in Africa, including other Lusophone countries. 1 Gender and Mediation in Guinea-Bissau: The Group of Women Facilitators Introduction On July 10, 2017, the President of Guinea Bissau, José Mário Vaz, met politician Domingos Simões Pereira, who had served as Prime Minister from 2014 to August 2015. Although Pereira remained head of the country’s major political party, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cabo Verde (PAIGC), he had been dismissed (along with the entire cabinet) by the president in August 2015 during a power struggle between the two men. -

Sanctuary Lost: the Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974

Sanctuary Lost: The Air War for ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, 1963-1974 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Martin Hurley, MA Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee: Professor John F. Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Alan Beyerchen Professor Ousman Kobo Copyright by Matthew Martin Hurley 2009 i Abstract From 1963 to 1974, Portugal and the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde, or PAIGC) waged an increasingly intense war for the independence of ―Portuguese‖ Guinea, then a colony but today the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. For most of this conflict Portugal enjoyed virtually unchallenged air supremacy and increasingly based its strategy on this advantage. The Portuguese Air Force (Força Aérea Portuguesa, abbreviated FAP) consequently played a central role in the war for Guinea, at times threatening the PAIGC with military defeat. Portugal‘s reliance on air power compelled the insurgents to search for an effective counter-measure, and by 1973 they succeeded with their acquisition and employment of the Strela-2 shoulder-fired surface-to-air missile, altering the course of the war and the future of Portugal itself in the process. To date, however, no detailed study of this seminal episode in air power history has been conducted. In an international climate plagued by insurgency, terrorism, and the proliferation of sophisticated weapons, the hard lessons learned by Portugal offer enduring insight to historians and current air power practitioners alike. -

Women Fighters and National Liberation in Guinea Bissau Aliou Ly

24 | Feminist Africa 19 Promise and betrayal: Women fighters and national liberation in Guinea Bissau Aliou Ly Introduction Guinea Bissau presents an especially clear-cut case in which women’s mass participation in the independence struggle was not followed by sustained commitment to women’s equality in the post-colonial period. Amilcar Cabral of Guinea Bissau and his party, the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC), realised that the national liberation war could not succeed without women’s participation, not only as political agents but also as fighters. Cabral also understood, and attempted to convince his male Party members, that a genuine national liberation meant liberation not only from colonialism but also from all the local traditional socio-cultural forces, both pre-colonial and imposed by the Portuguese rulers, that excluded women from decision-making structures at every level of society. Sadly, many of the former women fighters also say that male PAIGC members did not fulfil promises of socio-political, economic and gender equality that were crucial to genuine social transformation. Because women participated in bringing about independence in very dramatic ways, because the Party that came to power actually promised equality, and because the Party then had women return to their traditional subordinate roles, Guinea Bissau provides an especially clear case for exploring the relation in Africa between broken promises to women and the unhappiness reflected in the saying “Africa is growing but not developing”. In May 2013, Africa’s Heads of State celebrated the 50th Anniversary of the Organisation of African Unity in a positive mood because of a rising GDP and positive view about African economies. -

Download the List of Participants

46 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS Socialfst International BULGARIA CZECH AND SLOVAK FED. FRANCE Pierre Maurey Bulgarian Social Democratic REPUBLIC Socialist Party, PS Luis Ayala Party, BSDP Social Democratic Party of Laurent Fabius Petar Dertliev Slovakia Gerard Fuchs Office of Willy Brandt Petar Kornaiev Jan Sekaj Jean-Marc Ayrault Klaus Lindenberg Dimit rin Vic ev Pavol Dubcek Gerard Collomb Dian Dimitrov Pierre Joxe Valkana Todorova DENMARK Yvette Roudy Georgi Kabov Social Democratic Party Pervenche Beres Tchavdar Nikolov Poul Nyrup Rasmussen Bertrand Druon FULL MEMBER PARTIES Stefan Radoslavov Lasse Budtz Renee Fregosi Ralf Pittelkow Brigitte Bloch ARUBA BURKINA FASO Henrik Larsen Alain Chenal People's Electoral Progressive Front of Upper Bj0rn Westh Movement, MEP Volta, FPV Mogens Lykketoft GERMANY Hyacinthe Rudolfo Croes Joseph Ki-Zerbo Social Democratic Party of DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Germany, SPD ARGENTINA CANADA Dominican Revolutionary Bjorn Entolm Popular Socialist Party, PSP New Democratic Party, Party, PRD Hans-Joe en Vogel Guillermo Estevez Boero NDP/NPD Jose Francisco Pena Hans-Ulrich Klose Ernesto Jaimovich Audrey McLaughlin Gomez Rosemarie Bechthum Eduardo Garcia Tessa Hebb Hatuey de Camps Karlheinz Blessing Maria del Carmen Vinas Steve Lee Milagros Ortiz Bosch Hans-Eberhard Dingels Julie Davis Leonor Sanchez Baret Freimut Duve AUSTRIA Lynn Jones Tirso Mejia Ricart Norbert Gansel Social Democratic Party of Rejean Bercier Peg%:'. Cabral Peter Glotz Austria, SPOe Diane O'Reggio Luz el Alba Thevenin Ingamar Hauchler Franz Vranitzky Keith -

Searchable PDF Format

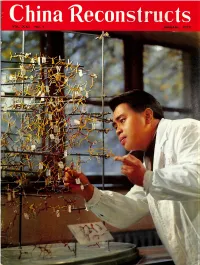

u r S" ';i f; V n -I \ , - .r.' K*.- ♦ . .^- •*?>' •r^ , -'.. ilBra ^ • wet h —„__ • -?' • -.- . rf - • -T •• VOL. XXI NO. 1 JANUARY 1972 PUBLISHED MONTHLY IN ENGLISH, FRENCH, SPANISH, ARABIC and RUSSIAN BY THE CHINA WELFARE INSTITUTE (SOONG CHING LING, CHAIRMAN) CONTENTS THE BEGINNING OF A NEW ERA Soong Ching Ling 2 CHINESE DELEGATION SPEAKS AT THE UNITED NATIONS 6 SOME BASIC FACTS ABOUT THE PEOPLE'S COMMUNES 10 SANDSTONE HOLLOW'S TWENTY-YEAR BAT TLE Chang Kuei-shun 14 KOREAN, ROMANIAN AND JAPANESE ART ISTS IN CHINA 21 DOMINGOS, IMMORTAL AFRICAN FIGHTER 26 CHANGES IN THE BIG FOREST Ma Yung-shun 28 TRAINING DEER FOR HERDING 35 LIVING IN CHINA (POEM) Rewi Alley 36 LANGUAGE CORNER; AN EXAMPLE OF COVER PICTURES: SERVING THE PEOPLE 37 Front: A researcher of the Chinese Academy of DETERMINING INSULIN CRYSTAL STRUC Sciences constructs a model TURE—ANOTHER STEP FORWARD IN showing the spatial structure PROTEIN RESEARCH 38 of insulin, based on analysis of an electron density map CHINA'S GEOGRAPHY: THE RIVERS OF (see story on p. 38). CHINA 41 Inside front: A new oilfield STAMPS: TAKING TIGER MOUNTAIN BY ' in Chinghai province. STRATEGY 45 Back: A view of the Ichun forest area in the Lesser NOTABLE PROGRESS IN CHINA'S INDUSTRY Khingan Mountains in north AND AGRICULTURE 46 east China (see story on p. 28). Inside bock: Wheat harvest at the Pei-an County State Editorial Office: Wot Wen Building, Peking (37), China. Farm, Heilungkiang prov- Coble: "CHIRECON" Peking. General Distributor; GUOZI SHUDIAN, P.O. Box 399, Peking, China. The Beginning of a N The announced visit of the U.S.