Maritime Transport Crisis / 1Hansj

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

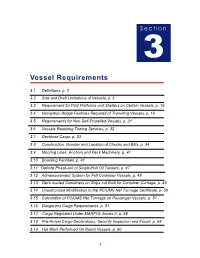

Section 3 2018 Edition

S e c ti o n 3 Vessel Requirements 3.1 Definitions, p. 2 3.2 Size and Draft Limitations of Vessels, p. 4 3.3 Requirement for Pilot Platforms and Shelters on Certain Vessels, p. 16 3.4 Navigation Bridge Features Required of Transiting Vessels, p. 19 3.5 Requirements for Non-Self-Propelled Vessels, p. 31 3.6 Vessels Requiring Towing Services, p. 32 3.7 Deckload Cargo, p. 33 3.8 Construction, Number and Location of Chocks and Bitts, p. 34 3.9 Mooring Lines, Anchors and Deck Machinery, p. 41 3.10 Boarding Facilities, p. 41 3.11 Definite Phase-out of Single-Hull Oil Tankers, p. 47 3.12 Admeasurement System for Full Container Vessels, p. 48 3.13 Deck-loaded Containers on Ships not Built for Container Carriage, p. 49 3.14 Unauthorized Modification to the PC/UMS Net Tonnage Certificate, p. 50 3.15 Calculation of PC/UMS Net Tonnage on Passenger Vessels, p. 51 3.16 Dangerous Cargo Requirements, p. 51 3.17 Cargo Regulated Under MARPOL Annex II, p. 58 3.18 Pre-Arrival Cargo Declarations, Security Inspection and Escort, p. 58 3.19 Hot Work Performed On Board Vessels, p. 60 1 OP Operations Manual Section 3 2018 Edition 3.20 Manning Requirements, p. 61 3.21 Additional Pilots Due to Vessel Deficiencies, p. 62 3.22 Pilot Accommodations Aboard Transiting Vessels, p. 63 3.23 Main Source of Electric Power, p. 63 3.24 Emergency Source of Electrical Power, p. 63 3.25 Sanitary Facilities and Sewage Handling, p. -

ONI-54-A.Pdf

r~us U. S. FLEET TRAIN- Division cf Naval Intelligence-Identification and Characteristics Section e AD Destroyer Tenders Page AP Troop Transports Pa g e t Wo "'W" i "~ p. 4-5 z MELVILLE 28 5 BURROWS 14 3, 4 DOBBIN Class 4 7 WHARTON 9 9 BLACK HAWK 28 21, 22 WAKEFIELD Class 12 11, 12 ALTAIR Class 28 23 WEST POINT 13 14, 15, 17-19 DIXIE Class 7 24 ORIZABA 13 16 CASCADE 10 29 U. S. GRANT 14 20,21 HAMUL Class 22 31, 3Z CHATEAU THIERRY Class 9 33 REPUBLIC 14 AS Submarine Tenders 41 STRATFORD 14 3 HOLLAND 5 54, 61 HERMIT AGE Class 13 5 BEAVER 16 63 ROCHAMBEAU 12 11, 12, 15 19 FULTON Class 7 67 DOROTHEA L. DIX 25 Sin a ll p. H 13, 14 GRIFFIN Class 22 69- 71,76 ELIZ . STANTON Cla ss 23 20 OTUS 26 72 SUSAN B. ANTHONY 15 21 AN TEA US 16 75 GEMINI 17 77 THURSTON 20 AR Repair Ships 110- "GENERAL" Class 10 1 MEDUSA 5 W orld W ar I types p. 9 3, 4 PROMETHEUS Class 28 APA Attack Transports 5- VULCAN Class 7 1, 11 DOYEN Class 30 e 9, 12 DELTA Class 22 2, 3, 12, 14- 17 HARRIS Class 9 10 ALCOR 14 4, 5 McCAWLEY , BARNETT 15 11 RIGEL 28 6-9 HEYWOOD Class 15 ARH Hull Repair Ships 10, 23 HARRY LEE Class 14 Maritime types p. 10-11 13 J T. DICKMAN 9 1 JASON 7 18-zo; 29, 30 PRESIDENT Class 10 21, 28, 31, 32 CRESCENT CITY Class 11 . -

US Maritime Administration

U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) Shipping and Shipbuilding Support Programs January 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46654 SUMMARY R46654 U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) January 8, 2021 Shipping and Shipbuilding Support Programs Ben Goldman The U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) is one of the 11 operating administrations of the Analyst in Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). Its mission is to develop the merchant maritime Policy industry of the United States. U.S. maritime policy, largely set out by the Merchant Marine Acts of 1920 and 1936 and with some roots in even older legislation, is codified in Subtitle V of Chapter 46 of the U.S. Code. As currently articulated, it is the policy of the United States to “encourage and aid the development and maintenance of a merchant marine” that meets the objectives below, which MARAD helps to achieve via the following programs and activities: Carry domestic waterborne commerce and a substantial part of the waterborne export and import foreign commerce of the United States. International shipping is dominated by companies using foreign- owned or foreign-registered vessels taking advantage of comparatively lower operating costs. The MARAD Maritime Security Program (MSP) supports U.S.-flagged ships engaged in international commerce by providing annual subsidies to defray the operating costs of up to 60 vessels. Originally scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, authorization for MSP was extended through 2035 by the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92). Similar programs were established to support tankers and cable-laying ships, either in that same law or in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 (P.L. -

Revolutionizing Short Sea Shipping Positioning Report

Revolutionizing short sea shipping Positioning Report Magnus Gustafsson Tomi Nokelainen Anastasia Tsvetkova Kim Wikström Åbo Akademi University Revolutionizing short sea shipping Positioning Report Executive summary Shipping in the Baltic Sea forms an essential part of Finnish • Establishing real-time integrated production and logistic industry. At present, the utilization rate of bulk and general planning to ensure optimized just-in-time freight through- cargo ships serving Finland is under 40%, and the old-fash- out the logistic chain. ioned routines in ports lead to ships sailing at non-optimal • Introducing a new cargo handling concept developed by speeds and thereby to unnecessary fuel consumption. Lack of MacGregor that reduces turnaround time in ports, maxi- transparency and coordination between the large numbers of mizes cargo space utilization, and secures cargo handling actors in logistical chains is the key reason for inefficiencies in quality. sea transportation, operations in ports, and land transporta- • Employing a performance-driven shipbuilding and opera- tion. Addressing these inefficiencies could increase the com- tion business model that ensures a highly competitive ship petitiveness of Finnish industry, and, at the same time, create by keeping world-leading technology providers engaged a basis for significant exports. throughout the lifecycle of vessels. By changing the business models and ways of working • Implementing new financing models that integrate insti- it would be possible to lower cargo transportation costs by tutional investors with a long-term investment perspective 25-35% and emissions by 30-35% in the dry bulk and general in order to reduce the cost of capital and put the focus on cargo logistics in the Baltic Sea area. -

Global Shipping: Choosing the Best Method of Transport

Global Shipping: Choosing the Best Method of Transport When shipping freight internationally, it’s important to choose the appropriate mode of transportation to ensure your products arrive on time and at the right cost. Your decision to ship by land, sea, or air depends on a careful evaluation of business needs and a comparison of the benefits each method affords. Picking the best possible mode of transportation is critical to export success. Shipping by truck Shipping by truck is a popular method of freight transport used worldwide, though speed and quality of service decline outside of industrialized areas. Even if you choose to ship your products by sea or air, a truck is usually responsible for delivering the goods from the port of arrival to their final destination. When shipping by truck, the size of your shipment will determine whether you need less- than-truckload (LTL) or truckload (TL) freight. LTL involves smaller orders, and makes up the majority of freight shipments. The average piece of LTL freight weighs about 1,200 pounds and is the size of a single pallet. However, LTL freight can range from 100 to 15,000 pounds. Beyond this limit, your shipment is likely to be classified as truckload freight. It is more economical for large shipments to utilize the space and resources of a single motor carrier, instead of being mixed with other shipments and reloaded into several different vehicles along the route. TL providers generally charge a ‘per mile’ rate, which can vary depending on distance, items being shipped, equipment, and service times. -

Investigation of Abandoned WW II Wrecks in Palau

Investigation of Abandoned WW II Wrecks in Palau Tomo Ishimura1 Abstract Over forty Japanese vessels were sunken in the water of Palau during WWII. Some wrecks sunk in the shallow water at a depth of 20 meters or less and were salvaged. Other wrecks at 30 meters depth or more still remain and are legally protected by the authority of Palau Government but are seriously threatened by illegal treasure hunters. Initial efforts to identify human remains of Japanese soldiers were made in 2005. As part of an archaeology advisory team for the Japanese Government I carried out underwater surveys of sunken WWII vessels in Palau. In 2010 and 2011, I conducted investigations of the WWII vessels again, together with on-shore research on sites and features associated with the Japanese occupation period, funded by the Takanashi Foundation for Arts and Archaeology (Japan). The research revealed that the most of the vessels sunken in Palau were not genuine military vessels of Japanese Imperial Navy or Army but converted vessels originally built for non-combat purposes. These vessels were slow in speed and not well-equipped for combat activity. Most of them were destroyed by American aerial bombing on March 30th 1944. The evening before (March 29th) the main force of the Japanese Combined Fleet, including its flagship Musashi, retreated from Palau. It is clear that the vessels left in Palau were abandoned as a “third wheel” of the Combined Fleet. These abandoned-converted vessels include cargo carriers, tankers, whaling boats and fishing boats. This implies that Japanese troops were experiencing a difficult and desperate campaign at that time. -

RO-RO Cargo Vessel FERRIES & RO-RO, YACHTS, HIGH SPEED BOATS

RO-RO Cargo Vessel FERRIES & RO-RO, YACHTS, HIGH SPEED BOATS 27,000 DWT Builder / Yard No.: Shipyard 3. MAJ / 2788 Owner / Flag: CMA-CGM / BAHAMAS Designed by: Shipyard 3. MAJ The vessel is RO-RO ship suitable to carry containers, trucks, trailers, general cargo and cars and vans on hoistable deck. Cargo space is divided into two (2) forward cargo holds with 40’ cellguides and one (1) cargo space divided with decks into three (3) garages, and cargo space on weatherdeck with container fittings. Double bottom and side arranged for ballast water, HFO and antiheeling tanks. The ship’s hull is specially equipped for in-water surveys. Engine room is equipped for unattended operation. Classification: BV Cargo equipment I W HULL W MACH • Stern quarter ramp: 46.5 m (incl. flap) x 12.0 m/250 t RO-RO cargo ship, equipped for capacity, four (4) wheels axle load 60 t carriage of containers • Stern door: 27.0 m x 7.0 m Unrestricted navigation • Car decks: W AUT-UMS, W SYS-NEQ1 2A area abt. 2300 m2 eleven (11) hoisting panels MON-SHAFT, INWATER SURVEY 3A area abt. 3480 m2 seventeen (17) hoisting panels, starboard aft panel use as ramp Length overall (extreme) 211.60 m • Fixed ramp lower deck to tank top: 28.3 m x 8.0 m with Length between perpendiculars 190.00 m gastight hydraulically operated ramp cover Breadth, moulded 32.20 m middle deck to lower deck: 57.4 m x 12.0 m with Depth, moulded to weather deck 22.70 m watertight hydraulically operated ramp cover Design draught (extreme) 10.50 m middle to weather deck: 53.4 m x 8.0 m with Deadweight at design draught 26,700 t watertight hydraulically operated ramp cover Main engine 3. -

A Novel Cargo Ship Detection and Directional Discrimination Method for Remote Sensing Image Based on Lightweight Network

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article A Novel Cargo Ship Detection and Directional Discrimination Method for Remote Sensing Image Based on Lightweight Network Pan Wang, Jianzhong Liu *, Yinbao Zhang, Zhiyang Zhi, Zhijian Cai and Nannan Song School of Geoscience and Technology, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou 450001, China; [email protected] (P.W.); [email protected] (Y.Z.); [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (Z.C.); [email protected] (N.S.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Recently, cargo ship detection in remote sensing images based on deep learning is of great significance for cargo ship monitoring. However, the existing detection network is not only unable to realize autonomous operation on spaceborne platforms due to the limitation of computing and storage, but the detection result also lacks the directional information of the cargo ship. In order to address the above problems, we propose a novel cargo ship detection and directional discrimination method for remote sensing images based on a lightweight network. Specifically, we design an efficient and lightweight feature extraction network called the one-shot aggregation and depthwise separable network (OSADSNet), which is inspired by one-shot feature aggregation modules and depthwise separable convolutions. Additionally, we combine the RPN with the K-Mean++ algorithm to obtain the K-RPN, which can produce a more suitable region proposal for cargo ship detection. Citation: Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Furthermore, without introducing extra parameters, the directional discrimination of the cargo ship Zhi, Z.; Cai, Z.; Song, N. A Novel is transformed into a classification task, and the directional discrimination is completed when the Cargo Ship Detection and Directional detection task is completed. -

Basic Concepts of Maritime Transport and Its Present Status in Latin America and the Caribbean

or. iH"&b BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN . ' ftp • ' . J§ WAC 'At 'li ''UWD te. , • • ^ > o UNITED NATIONS 1 fc r> » t 4 CR 15 n I" ti i CUADERNOS DE LA CEP AL BASIC CONCEPTS OF MARITIME TRANSPORT AND ITS PRESENT STATUS IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN UNITED NATIONS Santiago, Chile, 1987 LC/G.1426 September 1987 This study was prepared by Mr Tnmas Sepûlveda Whittle. Consultant to ECLAC's Transport and Communications Division. The opinions expressed here are the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily coincide with those of the United Nations. Translated in Canada for official use by the Multilingual Translation Directorate, Trans- lation Bureau, Ottawa, from the Spanish original Los conceptos básicos del transporte marítimo y la situación de la actividad en América Latina. The English text was subse- quently revised and has been extensively updated to reflect the most recent statistics available. UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATIONS Sales No. E.86.II.G.11 ISSN 0252-2195 ISBN 92-1-121137-9 * « CONTENTS Page Summary 7 1. The importance of transport 10 2. The predominance of maritime transport 13 3. Factors affecting the shipping business 14 4. Ships 17 5. Cargo 24 6. Ports 26 7. Composition of the shipping industry 29 8. Shipping conferences 37 9. The Code of Conduct for Liner Conferences 40 10. The Consultation System 46 * 11. Conference freight rates 49 12. Transport conditions 54 13. Marine insurance 56 V 14. -

'Liberty'cargo Ship

‘LIBERTY’ CARGO SHIP FEATURE ARTICLE written by James Davies for KEY INFORMATION Country of Origin: United States of America Manufacturers: Alabama Dry Dock Co, Bethlehem-Fairfield Shipyards Inc, California Shipbuilding Corp, Delta Shipbuilding Co, J A Jones Construction Co (Brunswick), J A Jones Construction Co (Panama City), Kaiser Co, Marinship Corp, New England Shipbuilding Corp, North Carolina Shipbuilding Co, Oregon Shipbuilding Corp, Permanente Metals Co, St Johns River Shipbuilding Co, Southeastern Shipbuilding Corp, Todd Houston Shipbuilding Corp, Walsh-Kaiser Co. Major Variants: General cargo, tanker, collier, (modifications also boxed aircraft transport, tank transport, hospital ship, troopship). Role: Cargo transport, troop transport, hospital ship, repair ship. Operated by: United States of America, Great Britain, (small quantity also Norway, Belgium, Soviet Union, France, Greece, Netherlands and other nations). First Laid Down: 30th April 1941 Last Completed: 30th October 1945 Units: 2,711 ships laid down, 2,710 entered service. Released by WW2Ships.com USA OTHER SHIPS www.WW2Ships.com FEATURE ARTICLE 'Liberty' Cargo Ship © James Davies Contents CONTENTS ‘Liberty’ Cargo Ship ...............................................................................................................1 Key Information .......................................................................................................................1 Contents.....................................................................................................................................2 -

Master's Thesis

SUBS, SWARMS, AND STRICKEN INFRASTRUCTURE: THE VULNERABILITY OF THE UNITED STATES TO NON-TRADITIONAL TERRORIST THREATS by Patrick Collman A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Global Security Studies Baltimore, Maryland May 2017 © 2017 Patrick Collman All Rights Reserved Abstract: The lack of mass casualty domestic attacks in the United States, carried out by foreign fighters, since 9/11 should not be taken for a sign of future invulnerability. Major Islamic terrorist organizations have previously conducted attacks focused on splashy news headlines and high body counts. However, Al-Qaeda‟s original stated goal was to bankrupt the West, not kill everyone in it. Is the United States simply impervious to such an attack aimed at causing extensive financial or economic damage? Or is the United States vulnerable, and ultimately a sitting duck? This paper will argue the latter. By examining the relationships between Islamic terrorist organizations and drug- trafficking organizations in Central and South America, and investing the use of advanced narco-submarines by the latter, the goal is to explore a viable means for inserting a group of armed, trained men undetected into the United States. Case studies examine the effectiveness of swarm-style terrorist attacks when compared to WMD and lone-wolf terror attacks. Further case studies seek to highlight extensive vulnerabilities within the U.S. energy and economic infrastructure that, if taken offline via terrorist attack, would result in long-lasting and immensely expensive consequences if attacked. Were Al-Qaeda or another terrorist organization to decide that they wanted to hit America in the pocket book as opposed to racking up a body count, this paper seeks to show that they possess the means, the ability, and the opportunity to do so. -

Glossary International Freight Terms

GLOSSARY INTERNATIONAL FREIGHT TERMS ABI - Automated Brokerage Interface: Is a system available to U.S. Customs Brokers with the computer capabilities and customs certification to transmit and exchange customs entries and other information, facilitating prompt release of imported cargo. Acceptance: A time draft (or bill of exchange) which the drawee has accepted and is unconditionally obligated to pay at maturity. Drawee's act in receiving a draft and thus entering into the obligation to pay its value at maturity. An agreement to purchase goods under specified terms. Add Hoc Charter: A one-off charter operated at the necessity of an airline or charterer. Ad Valorem ("according to the value"): A fixed percentage of the value of goods that is used to calculate customs duties and taxes. Admiralty Court: Is a court having jurisdiction over maritime questions pertaining to ocean transport, including contracts, charters, collisions, and cargo damages. Advance Against Documents: Load made on the security of the documents covering the shipment. Advising Bank: A bank that receives a letter of credit from an issuing bank, verifies its authenticity, and forwards the original letter of credit to the exporter without obligation to pay. Advisory Capacity: A term indicating that a shipper's agent or representative is not empowered to make definite decisions or adjustment without the approval of the group or individual represented. Affiliate: Is a company that controls, or is controlled by another company, or is one of two or more commonly controlled companies. Airfreightment: An agreement by a steamship line to provide cargo space on a vessel at a specified time and for a specified price to accommodate an exporter or importer, who then becomes liable for payment even though he is later unable to make the shipment.