Investigation of Abandoned WW II Wrecks in Palau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecords of the War Department's I Operations Division, 1942-1945

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of World War II Research Collections ecords of the War Department's i Operations Division, 1942-1945 Part 1. World War II Operations Series C. Top Secret Files University Publications of America A Guide to ike Microfilm Edition of World War II Research Collections Records of the War Department's Operations Division, 1942-1945 Part 1. World War II Operations Series C. Top Secret Files Guide compiled by Blair D. Hydrick A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Records of the War Department's Operations Division, 1942-1945. Part 1, World War II operations [microform]. microfilm reels. • (World War II research collections) Accompanied by printed reel guide, compiled by Blair D. Hydrick. Includes index. Contents: ser. A. European and Mediterranean theaters • ser. B. Pacific theater • ser. C. top secret files. ISBN 1-55655-273-4 (ser. C: microfilm) 1. World War, 1939-1945•Campaigns•Sources. 2. United States. War Dept. Operations Division•Archives. I. Hydrick, Blair D. II. University Publications of America (Firm). IE. Series. [D743] 940.54'2•dc20 93-1467 CIP Copyright 1993 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-273-4. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction v Note on Sources ix Editorial Note ix Abbreviations x Reel Index 1942-1944 Reell 1 Reel 2 1 Reel 3 2 Reel 4 2 Reel5 3 Reel 6 : 3 Reel? 4 ReelS 5 Reel 9 5 Reel 10 6 Reel 11 6 Reel 12 7 Reel 13 7 Reel 14 8 Reel 15 8 Reel 16 9 Reel 17 9 Reel 18 10 1945 Reel 19 11 Reel 20 12 Reel 21 12 Reel 22 13 Reel 23 14 Reel 24 14 Reel 25 15 Reel 26 16 Subject Index 19 m INTRODUCTION High Command: The Operations Division of the War Department General Staff In 1946 the question originally posed to me was assistance than was afforded to many of his subordinate what the U.S. -

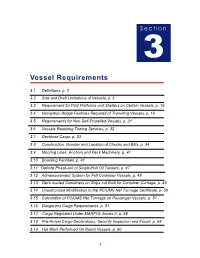

Section 3 2018 Edition

S e c ti o n 3 Vessel Requirements 3.1 Definitions, p. 2 3.2 Size and Draft Limitations of Vessels, p. 4 3.3 Requirement for Pilot Platforms and Shelters on Certain Vessels, p. 16 3.4 Navigation Bridge Features Required of Transiting Vessels, p. 19 3.5 Requirements for Non-Self-Propelled Vessels, p. 31 3.6 Vessels Requiring Towing Services, p. 32 3.7 Deckload Cargo, p. 33 3.8 Construction, Number and Location of Chocks and Bitts, p. 34 3.9 Mooring Lines, Anchors and Deck Machinery, p. 41 3.10 Boarding Facilities, p. 41 3.11 Definite Phase-out of Single-Hull Oil Tankers, p. 47 3.12 Admeasurement System for Full Container Vessels, p. 48 3.13 Deck-loaded Containers on Ships not Built for Container Carriage, p. 49 3.14 Unauthorized Modification to the PC/UMS Net Tonnage Certificate, p. 50 3.15 Calculation of PC/UMS Net Tonnage on Passenger Vessels, p. 51 3.16 Dangerous Cargo Requirements, p. 51 3.17 Cargo Regulated Under MARPOL Annex II, p. 58 3.18 Pre-Arrival Cargo Declarations, Security Inspection and Escort, p. 58 3.19 Hot Work Performed On Board Vessels, p. 60 1 OP Operations Manual Section 3 2018 Edition 3.20 Manning Requirements, p. 61 3.21 Additional Pilots Due to Vessel Deficiencies, p. 62 3.22 Pilot Accommodations Aboard Transiting Vessels, p. 63 3.23 Main Source of Electric Power, p. 63 3.24 Emergency Source of Electrical Power, p. 63 3.25 Sanitary Facilities and Sewage Handling, p. -

Steel Typhoon 1

Steel Typhoon 1 Steel Typhoon 2012 Standard The Second Half of the Pacific War November 1943 - September 1945 designed by Ed Kettler, Adam Adkins, and John Kettler edited by Larry Bond and Chris Carlson published by The Admiralty Trilogy Group Copyright © 2012, 2014, 2015, 2019 by the Admiralty Trilogy Group, LLC, Ed Kettler, Adam Adkins, and John Kettler All rights reserved. Printed in the USA. Made in the USA. No part of this game may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Command at Sea is a registered Trademark by Larry Bond, Christopher Carlson, and Edward Kettler, for their WW II tacti- cal naval wargame. The Admiralty Trilogy is a registered Trademark by Larry Bond, Christopher Carlson, Edward Kettler, and Michael Harris for their Twentieth-Century tactical naval gaming system. ThisSample version of Steel Typhoon has been updated to include all corrections from errata through 13 Octoberfile 2019. The designers of Steel Typhoon and Command at Sea are prepared to answer questions about the game system. They can be reached in care of the Admiralty Trilogy Group at [email protected]. Visit their website at www.admiraltytrilogy.com. Cover by Tim Schleif 2 Steel Typhoon Table of Contents Page Table of Contents 2 Scenario Notes 3 Dedication 3 Acknowledgements 3 Map of the Pacific Theater 4 Battleship and Cruiser Floatplane Availability 5 Japanese Naval Aviation Units 5 Hourly Event Table 6 Operation Cartwheel: Breaking the Solomons Barrier Raid on Rabaul 5 Nov 43 Carrier attack -

Anticipating Anchoring Story and Photos by Jeff Merrill

power voyaging Anticipating anchoring STORy ANd phOTOS by JEff MERRIll he freedom to explore which goes into great detail Let’s presume that the Tremote cruising grounds on a number of theoretical windlass (horizontal or verti- and to anchor out overnight aspects and practical applica- cal) and anchor (so many or for days at a time is one tions for a variety of situa- variations) have already been of the great attractions of tions. Over time voyagers selected and installed on the trawler lifestyle. Under- generally develop techniques your trawler and are appro- standing how your ground for setting their anchor, priately sized to provide breaking it loose and you with sufficient holding securely stowing the strength. With this article ground tackle while I’d like to share some com- underway — practice, mon sense techniques you fine-tune and keep can adapt to your trawler learning. that will improve your com- There are many fort level and to help you factors involved in “dial-in” your anchoring selecting a safe place routine. Be sure that the to drop the hook — connection between your wind, tide, currents, anchor and chain (swivel other boats, etc. You with Loctite or shackles with seizing wire on the pins) is secure so it can’t disconnect. Above, an tackle connects your Securing the anchor anchor bridle floating palace to the It is vitally important that setup evenly sea floor and being your anchor, when raised distributes the properly prepared will and stowed on its roller, load. Right, an give you more con- is secure in place and not anchor keeper fidence to visit new free to wobble around. -

Last Voyage of the Hornet: the Story That Made Mark Twain Famous

Last Voyage of the Hornet: The Story that Made Mark Twain Famous Kristin Krause Royal Fireworks Press Unionville, New York For Greg, Duncan, and Luke – Never give up. Copyright © 2016, Royal Fireworks Publishing Co., Inc. All Rights Reserved. Royal Fireworks Press P.O. Box 399 41 First Avenue Unionville, NY 10988-0399 (845) 726-4444 fax: (845) 726-3824 email: [email protected] website: rfwp.com ISBN: 978-0-88092-265-4 Printed and bound in Unionville, New York, on acid-free paper using vegetable-based inks at the Royal Fireworks facility. Publisher: Dr. T.M. Kemnitz Editors: Dr. T. M. Kemnitz, Rachel Semlyen, and Jennifer Ault Book and cover designer: Kerri Ann Ruhl 8s6 ps Chapter 1 The clipper ship Hornet drifted across the mirroring waters of the Pacific Ocean in a blistering hot calm. Not a breath of wind stirred on deck, but upper air currents filled the skysails and royals, gently propelling the vessel along. The morning air was already sweltering. The crew, all barefoot and mostly shirtless, moved lethargically in the tropical heat. Those not on duty sought shade where they could find it or lazily dangled fishing lines in the water. All the hatches, skylights, and portholes were open to admit air, making it tolerable for those below decks. Since crossing the equator two days before, the ship had been slipping slowly north through a series of hot and windless days. But that was about to change. The captain of the Hornet was Josiah Mitchell, fifty-three years old, capable and levelheaded, with an inexpressive face hidden under a bushy beard. -

From the Nisshin to the Musashi the Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku by Tal Tovy

Asia: Biographies and Personal Stories, Part II From the Nisshin to the Musashi The Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku By Tal Tovy Detail from Shugaku Homma’s painting of Yamamoto, 1943. Source: Wikipedia at http://tinyurl.com/nowc5hg. n the morning of December 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) aircraft set out on one of the most famous operations in military Ohistory: a surprise air attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawai`i. The attack was devised and fashioned by Admiral Yamamoto, whose entire military career seems to have been leading to this very moment. Yamamoto was a naval officer who appreciated and under- stood the strategic and technological advantages of naval aviation. This essay will explore Yamamoto’s military career in the context of Imperial Japan’s aggressive expansion into Asia beginning in the 1890s and abruptly ending with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, to the US and its Allies. Portrait of Yamamoto just prior to the Russo- Japanese War, 1905. Early Career (1904–1922) Source: World War II Database Yamamoto Isoroku was born in 1884 to a samurai family. Early in life, the boy, thanks to at http://tinyurl.com/q2au6z5. missionaries, was exposed to American and Western culture. In 1901, he passed the Impe- rial Naval Academy entrance exams with the objective of becoming a naval officer. Yamamoto genuinely respected the West—an attitude not shared by his academy peers. The IJN was significantly influenced by the British Royal Navy (RN), but for utilitarian reasons: mastery of technology, strategy, and tactics. -

ONI-54-A.Pdf

r~us U. S. FLEET TRAIN- Division cf Naval Intelligence-Identification and Characteristics Section e AD Destroyer Tenders Page AP Troop Transports Pa g e t Wo "'W" i "~ p. 4-5 z MELVILLE 28 5 BURROWS 14 3, 4 DOBBIN Class 4 7 WHARTON 9 9 BLACK HAWK 28 21, 22 WAKEFIELD Class 12 11, 12 ALTAIR Class 28 23 WEST POINT 13 14, 15, 17-19 DIXIE Class 7 24 ORIZABA 13 16 CASCADE 10 29 U. S. GRANT 14 20,21 HAMUL Class 22 31, 3Z CHATEAU THIERRY Class 9 33 REPUBLIC 14 AS Submarine Tenders 41 STRATFORD 14 3 HOLLAND 5 54, 61 HERMIT AGE Class 13 5 BEAVER 16 63 ROCHAMBEAU 12 11, 12, 15 19 FULTON Class 7 67 DOROTHEA L. DIX 25 Sin a ll p. H 13, 14 GRIFFIN Class 22 69- 71,76 ELIZ . STANTON Cla ss 23 20 OTUS 26 72 SUSAN B. ANTHONY 15 21 AN TEA US 16 75 GEMINI 17 77 THURSTON 20 AR Repair Ships 110- "GENERAL" Class 10 1 MEDUSA 5 W orld W ar I types p. 9 3, 4 PROMETHEUS Class 28 APA Attack Transports 5- VULCAN Class 7 1, 11 DOYEN Class 30 e 9, 12 DELTA Class 22 2, 3, 12, 14- 17 HARRIS Class 9 10 ALCOR 14 4, 5 McCAWLEY , BARNETT 15 11 RIGEL 28 6-9 HEYWOOD Class 15 ARH Hull Repair Ships 10, 23 HARRY LEE Class 14 Maritime types p. 10-11 13 J T. DICKMAN 9 1 JASON 7 18-zo; 29, 30 PRESIDENT Class 10 21, 28, 31, 32 CRESCENT CITY Class 11 . -

Chuuktext and Photos by Brandi Mueller

Wreck Junkie Heaven ChuukText and photos by Brandi Mueller 49 X-RAY MAG : 53 : 2013 EDITORIAL FEATURES TRAVEL NEWS WRECKS EQUIPMENT BOOKS SCIENCE & ECOLOGY TECH EDUCATION PROFILES PHOTO & VIDEO PORTFOLIO travel Chuuk View of Chuuk Island. PREVIOUS PAGE: Diver in interior of Betty plane My dream history lesson includes a tropical Pacific island where I step off a beautiful boat soaked in sunshine the warm Micronesian waters and descend on a coral cov- ered ship that was part of World War II. This dream and these ships came to life for me during a recent trip aboard the MV Odyssey liveaboard. Truk Lagoon, now known as Chuuk, is most certainly one of the world’s greatest wreck diving destinations. These lush green islands with palm trees and calm blue waters make it almost impossible to fathom the immense battle that took place on the 17th and 18th of February, 1944. Under Japanese occupation dur- the United States took Japan by battleships, numerous cruisers, ing World War II, Truk served as almost complete surprise with two destroyers, submarines and other one of the Japanese Imperial days of daytime and nighttime support ships assisting the carriers. Navy’s main bases in the South airstrikes, surface ship actions, Airstrikes, employed fighters, Pacific Theater. Some compared and submarine attacks. Ordered dive bombers and torpedo air- it as Japan’s Pearl Harbor. This by Admiral Raymond Spruance, craft were used in the attacks logistical and operations base Vice Admiral Marc A Mitscher’s focusing on airfields, aircraft, shore for the Japanese Combine Fleet Task Force 58 included five fleet installations, and ships around the served as the stage for the United carriers (the USS Enterprise, USS Truk anchorage throughout the States’ attack called Operation Yorktown, USS Essex, USS Intrepid, day and night. -

US Maritime Administration

U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) Shipping and Shipbuilding Support Programs January 8, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R46654 SUMMARY R46654 U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) January 8, 2021 Shipping and Shipbuilding Support Programs Ben Goldman The U.S. Maritime Administration (MARAD) is one of the 11 operating administrations of the Analyst in Transportation U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT). Its mission is to develop the merchant maritime Policy industry of the United States. U.S. maritime policy, largely set out by the Merchant Marine Acts of 1920 and 1936 and with some roots in even older legislation, is codified in Subtitle V of Chapter 46 of the U.S. Code. As currently articulated, it is the policy of the United States to “encourage and aid the development and maintenance of a merchant marine” that meets the objectives below, which MARAD helps to achieve via the following programs and activities: Carry domestic waterborne commerce and a substantial part of the waterborne export and import foreign commerce of the United States. International shipping is dominated by companies using foreign- owned or foreign-registered vessels taking advantage of comparatively lower operating costs. The MARAD Maritime Security Program (MSP) supports U.S.-flagged ships engaged in international commerce by providing annual subsidies to defray the operating costs of up to 60 vessels. Originally scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, authorization for MSP was extended through 2035 by the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2020 (P.L. 116-92). Similar programs were established to support tankers and cable-laying ships, either in that same law or in the NDAA for Fiscal Year 2021 (P.L. -

Revolutionizing Short Sea Shipping Positioning Report

Revolutionizing short sea shipping Positioning Report Magnus Gustafsson Tomi Nokelainen Anastasia Tsvetkova Kim Wikström Åbo Akademi University Revolutionizing short sea shipping Positioning Report Executive summary Shipping in the Baltic Sea forms an essential part of Finnish • Establishing real-time integrated production and logistic industry. At present, the utilization rate of bulk and general planning to ensure optimized just-in-time freight through- cargo ships serving Finland is under 40%, and the old-fash- out the logistic chain. ioned routines in ports lead to ships sailing at non-optimal • Introducing a new cargo handling concept developed by speeds and thereby to unnecessary fuel consumption. Lack of MacGregor that reduces turnaround time in ports, maxi- transparency and coordination between the large numbers of mizes cargo space utilization, and secures cargo handling actors in logistical chains is the key reason for inefficiencies in quality. sea transportation, operations in ports, and land transporta- • Employing a performance-driven shipbuilding and opera- tion. Addressing these inefficiencies could increase the com- tion business model that ensures a highly competitive ship petitiveness of Finnish industry, and, at the same time, create by keeping world-leading technology providers engaged a basis for significant exports. throughout the lifecycle of vessels. By changing the business models and ways of working • Implementing new financing models that integrate insti- it would be possible to lower cargo transportation costs by tutional investors with a long-term investment perspective 25-35% and emissions by 30-35% in the dry bulk and general in order to reduce the cost of capital and put the focus on cargo logistics in the Baltic Sea area. -

Global Shipping: Choosing the Best Method of Transport

Global Shipping: Choosing the Best Method of Transport When shipping freight internationally, it’s important to choose the appropriate mode of transportation to ensure your products arrive on time and at the right cost. Your decision to ship by land, sea, or air depends on a careful evaluation of business needs and a comparison of the benefits each method affords. Picking the best possible mode of transportation is critical to export success. Shipping by truck Shipping by truck is a popular method of freight transport used worldwide, though speed and quality of service decline outside of industrialized areas. Even if you choose to ship your products by sea or air, a truck is usually responsible for delivering the goods from the port of arrival to their final destination. When shipping by truck, the size of your shipment will determine whether you need less- than-truckload (LTL) or truckload (TL) freight. LTL involves smaller orders, and makes up the majority of freight shipments. The average piece of LTL freight weighs about 1,200 pounds and is the size of a single pallet. However, LTL freight can range from 100 to 15,000 pounds. Beyond this limit, your shipment is likely to be classified as truckload freight. It is more economical for large shipments to utilize the space and resources of a single motor carrier, instead of being mixed with other shipments and reloaded into several different vehicles along the route. TL providers generally charge a ‘per mile’ rate, which can vary depending on distance, items being shipped, equipment, and service times. -

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto Memorial Museum Chief of the Combined Fleet

Tracing the Life of Isoroku Yamamoto, a Man of Affection and Integrity AdmiralAdmiral IsorokuIsoroku YamamotoYamamoto MemorialMemorial MuseumMuseum Isoroku Takano, born to the family of a Confucian scholar in 1884, was an intelligent youth and respected Benjamin Franklin since his junior high school days. He studied very hard and acquired a broad knowledge of various things. Becoming the successor of the family of Tatewaki Yamamoto, a councilor of the feudal lord in the old Nagaoka Domain, Isoroku married a daughter of a samurai family of the old Aizu Feudal Domain. While mastering the arts of both the pen and the sword, working with a spirit of fortitude and vigor, and following a motto that showed the spirit of Nagaoka (“always have the spirit of being on a battlefield”), he focused his attention on petroleum and aviation early on in his career. Inspired by Lindbergh’s non-stop transatlantic flight, he especially stressed the signifi- cance of aviation. At the outbreak of the Pacific War, his foresight about aviation was proven to the world. However, Yamamoto firmly opposed the outbreak of the war. Taking the risk upon himself, he strongly opposed the Japan- Germany-Italy Triple Alliance, stating that his spirit would not be defeated even if his physical body were destroyed. His way of thinking may have been a direct result of his sincere love and affection for his hometown and the people. Despite his objections to joining the war, Yamamoto commanded the unprecedented battle as the Commander-in- Front View of the Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto Memorial Museum Chief of the Combined Fleet.